[Page 123][Editor’s Note: This article is an updated and extended version of a presentation given at the Third Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference: The Temple on Mount Zion, November 5, 2016, at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. For a video version of the presentation, see https://interpreterfoundation.org/conferences/2016-temple-on-mount-zion-conference/2016-temple-on-mount-zion-conference-videos/]

Abstract: In chapter 3 of the Gospel of John, Jesus described spiritual rebirth as consisting of two parts: being “born of water and of the spirit.”1 To this requirement of being “born again into the kingdom of heaven, of water, and of the Spirit,” Moses 6:59–60 adds that one must “be cleansed by blood, even the blood of mine Only Begotten; … For … by the blood ye are sanctified.”2 In this article, we will discuss the symbolism of water, spirit, and blood in scripture as they are actualized in the process of spiritual rebirth. We will highlight in particular the symbolic, salvific, interrelated, additive, retrospective, and anticipatory nature of these ordinances within the allusive and sometimes enigmatic descriptions of John 3 and Moses 6. Moses 6:51–68, with its dense infusion of temple themes, was revealed to the Prophet in December 1830, when the Church was in its infancy and more than a decade before the fulness of priesthood ordinances was made available to the Saints in Nauvoo. Our study of these chapters informs our closing perspective on the meaning of the sacrament, which is consistent with the recent re-emphasis of Church leaders that the “sacrament is a beautiful time to not just renew our baptismal covenants, but to commit to Him to renew all our covenants.”3 We discuss the relationship of the sacrament to the shewbread of Israelite temples, and its anticipation of the heavenly feast that will be enjoyed by those who have been sanctified by the blood of Jesus Christ.

Video presentation of paper with artwork

[Page 124]

Introduction: What Does It Mean To Be Born Again?

One of the most illuminating stories in the Gospel of John tells of Nicodemus’ confidential visit to inquire of Jesus.4 John portrays Nicodemus as a prime example of one of those who had initially “believed in [Christ’s] name, when they saw the miracles which he did. But,” as John explains, “Jesus did not commit himself unto [such], because he knew all men” and “he knew what was in man.”5 Though Nicodemus was one “of the Pharisees,”6 “a ruler of the Jews,”7 and a “master of Israel,”8 he struggled to grasp the meaning of what Jesus tried to teach him.

In contrast to the untutored woman of Samaria in the following chapter of John, who met the Lord in the brightness of high noon,9 Nicodemus, then a blind leader of the blind,10 came to Jesus in the darkness of night.11 Happily, however, “the day dawn[ed], and the day star [arose] in [his heart].”12 Eventually, Nicodemus must have experienced the “birth from above” that he did not at first comprehend, for John tells us that, at great personal risk, he later defended Jesus before the chief priests and Pharisees13 and helped prepare the Lord’s body for burial.14

Like the humble Peter, whose early foibles are candidly presented in the Gospels, Nicodemus was not ashamed to share the private story of his transformation from wondering skeptic to devoted disciple. Indeed, it is possible that he was John’s eyewitness source for the account that we will now discuss in more detail.[Page 125]

Nicodemus opened the conversation with Jesus. His use of the pronoun “we” in his statement that “we know that thou art a teacher come from God”15 revealed that he was not merely speaking for himself but also for the governing body of the Jews to which he belonged. As the basis for the council’s belief that Jesus was a “teacher come from God,” Nicodemus explained: “No one is able to do the miraculous signs that you do unless God is with him.”16

Jesus did not affirm Nicodemus’ declaration. Instead, He countered it with a parallel assertion: “No one is able to see the kingdom of God unless they are born again.”17 The Master was saying that Nicodemus and his brethren were mistaken in taking Jesus’ miracles as the basis for their confidence in Him as a divine teacher. Though they had seen these signs, they did not see the kingdom of God.

To see the kingdom of God — and eventually to enter within it, said Jesus — one must be born again.18 Indeed, Joseph Smith taught that seeing the kingdom of God is a prerequisite for permanently entering into it.19 He further clarified that even to begin to see the kingdom of God “from the outside”20 (in the sense of acquiring an initial spiritual understanding of it), individuals must have a “change of heart,” “a portion of the Spirit” that would take “the vail from before their eyes,”21 as was later experienced by Cornelius.22 At first, however, Nicodemus resisted Jesus’ invitation to “behold” with an “eye of faith” those things that are “within the veil.”23

That said, Nicodemus’ astonishment at Jesus’ teaching was not an entirely negative thing. In later rabbinic literature, “marveling or wondering … form[ed] an important part of the process of gaining[Page 126]

knowledge.”24 For example, it was said of Rabbi Akiba that “his learning began with wonder and culminated with a crown, a symbol of his power … to bring hidden things to light.”25 Thus, Jesus’ words to Nicodemus that night, “Marvel not,”26 should not be understood as a peremptory dismissal of his interlocutor’s initial doubts but rather as a spur to his further faith and inquiry, as in His later directive to the wondering Thomas: “be not faithless, but believing.”27

Nevertheless, up to that moment Nicodemus had not had a change of heart. His eyes were still veiled. As a test of Nicodemus’ powers of spiritual perception, Jesus had used a double entendre, or double meaning, in His discussion on the subject of being “born again.” The Greek word anōthen and the corresponding Aramaic/Syriac expressions bar derish (bar dĕrîš) and men derish (men dĕrîš) can mean both “again” — a second time — and also “from above” — literally, “from the head.”28 Each time Jesus repeated the requirement for all men to be “born from above,” or in other words, “born of the Spirit,”29 Nicodemus heard only the most obvious, superficial meaning of the Savior’s saying, namely, that one must be “born again,” or rather, “born of the flesh,”30 mistakenly thinking that Jesus meant coming forth a “second time” from the “mother’s womb.”31

[Page 127]Gently rebuking Nicodemus’ lack of understanding,32 Jesus continued in verse 8 with a play on words that exploited the double meaning of “wind” and “Spirit” in both Greek (pneuma) and Hebrew (ruach). Although the invisible, immediate workings of the wind may be indirectly perceived by means of its “sound,”33 it is beyond the power of physical sensation to reveal “whence it cometh” or “whither it goeth.”34 This being the case with earthly wind, what hope has any mortal, save he is born from above, to understand movements that are governed by the unseen, divine “winds” of God’s Spirit, crucially including Jesus’ own celestial comings and goings?35 Jesus’ description of those who are vaguely sensible to the evidences of the “earthly”36 wind yet stone-blind to the hidden operations of the divinely discerned “heavenly”37 Spirit parallel His prior disavowal, in verses 2 and 3, of those who see the superficial signs of His mission yet lack the spiritual vision required to see the kingdom of God.

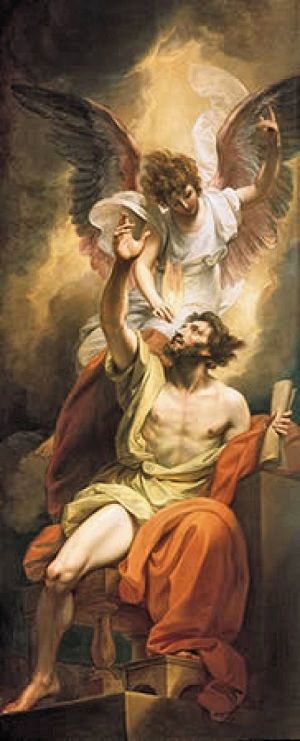

Jesus then directed his remarks more pointedly at Nicodemus and his brethren. Indeed, John’s phrasing of verse 11 seems to connect Nicodemus’ prior use of “we” in reference to the earthly council to which he belonged with Jesus’ use of the pronoun “we” in his reference to Himself and those of His prophetic predecessors who had, like Him, borne eyewitness testimony of the heavenly council: “Verily, verily, I say unto thee, We speak that we do know, and testify that we have seen; and ye [a plural pronoun referring to the Sanhedrin and its partisans] receive not our witness.”38 As Nicodemus surely realized, Jesus’ testimony implied not merely that He had seen the divine council but also that He had there received a divine commission, as echoed in the experience of Isaiah 6:8: “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? Then said I, Here am I; send me.”

[Page 128]Next, intensifying the drama of the dialogue, Jesus further described His commission. In doing so, He made it clear what it was not only to be justified and sanctified by water and the Spirit but also to be “lifted up” with power to traverse the veil in both directions as the “Son of man.”39 Once again, the Lord’s elaboration simultaneously disclosed and obscured40 His meaning:41

And no man hath ascended up to heaven, but he that came down from heaven, even the Son of man which is in heaven.

And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness,42 even so must the Son of man be lifted up:

That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life.

To comprehend the meaning of “lifted up” (from the Greek verb hypsoō) in Jesus’ words, we must first realize that, in the story of Moses, neither the serpents that bit the Israelites nor the figure on the standard that was “lifted up” by Moses were meant to be seen only as ordinary desert snakes. Rather, they are described in the rich language of Old Testament symbolism with the same Hebrew terms used elsewhere in scripture to refer to the glorious seraphim — divine messengers, proximal attendants of God’s throne,43 and preeminent members of the divine council. If we fail to connect the “fiery flying serpents”44 that were both the plague and the salvation of the children of Israel with the burning, godlike seraphim of the heavenly temple, we will lack the interpretive key for Jesus’ central teaching to Nicodemus.

Once we realize that, in another double entendre,45 Jesus has not only prophesied His atonement and death but also has compared Himself, as the “Son of Man,”46 to the seraphim that surround in intimate proximity the throne of the Father, the meaning of His statement that He was to be “lifted up” becomes apparent. In temple contexts, the essential function of the seraphim was similar to the role of the cherubim at the entrance of the Garden of Eden:47 they were to be sentinels or “keep[ers] [of] the way,”48 guarding the[Page 129]

![Figure 6. Marc Chagall (1887–1985): L’Exode, 1952–1966. “If I Be Lifted Up from the Earth, [I] Will Draw All Men Unto Me” (John 12:32).](https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/05-mystery-of-redemption-draw-all.jpg)

Figure 6. Marc Chagall (1887–1985): L’Exode, 1952–1966. “If I Be Lifted Up from the Earth, [I] Will Draw All Men Unto Me” (John 12:32).

Jesus’ application of the phrase “lifted up” to Himself is appropriate for other reasons. For example, the idea of His being “lifted up” ties back to Isaiah 52:13, a passage from a messianic “servant song”: “Behold, my servant shall deal prudently, he shall be exalted and extolled, and be very high.” Isaiah’s language in this chapter describes both the suffering and the exaltation of Jesus Christ. Significantly, however, in the Book of Mormon the resurrected Jesus Christ Himself applies Isaiah’s description of a “suffering servant” to the Prophet Joseph Smith, and the book of Moses applies similar language to Enoch.52 Consequently, it is clear that others in addition to Jesus Christ can be “lifted up” — becoming sons of Man53 and receiving “everlasting life”54 — through unwavering faithfulness in “the trial of [their] faith.”55 This is consistent with the explicit teaching in the first chapter of John that “as many as received [Christ], to them gave he power to become the sons of God”56 — in other words, to be born of God in the ultimate sense.[Page 130]

Note that the Greek phrase for “sons of God” used here, tekna theou, as well as its Hebrew equivalent, bĕnê (hā-)ʾĕlōhîm, are gender neutral in this and similar contexts. Although it would be possible to substitute the neutral term “children of God” in its place, we prefer to use the term “sons of God” — or exceptionally, when citing the discourse of King Benjamin, “sons … and daughters”57 of God. Although the Church teaches that every mortal, “in the beginning,”58 was a child “of heavenly parents,”59 there is a distinction made in the Gospel of John and elsewhere in scripture in which only the most faithful of God’s “offspring” are given “power to become the sons of God.”60

In short, whereas some readers equate the lifting up of Christ exclusively with His suffering in Gethsemane and His death on the cross, the means by which “whosoever believeth in him”61 may be sanctified and receive “everlasting life” through the shedding of His blood, a more careful examination of the passage makes it clear that John is exploiting a double meaning in the term “lifted up.” Should there be any doubt about the presence of subtle literary artistry in John’s account, consider the explicit confirmation of similar, deliberate wordplay in 3 Nephi 27. Within two verses, the resurrected Savior shifts aptly and seemingly effortlessly among multiple senses of “lifted up,” including “lifted up upon the cross,”62 “lifted up by men”63 in unrighteous judgment, “lifted up by the Father”64 in righteous judgment, and, ultimately, “lifted up at the last day” in exaltation.65

[Page 131]Similarly, in John 3 the “lifting up” of Jesus has as much to do with His heavenly ascent and glorious enthronement as it does with his ignominious death.66 Hence, according to Herman Ridderbos, “the crucifixion is not presented [by John] as Jesus’ humiliation but as the exaltation of the Son of Man,”67 a “birth from above” that He intended to share with His disciples. Thus, those who “look” and “begin to believe in the Son of God”68 as He is typologically revealed in the seraphic figure that has been “lifted up” will themselves, if they “endure to the end,” receive “eternal life,”69 being “lifted up” — in other words, exalted — with their Lord.

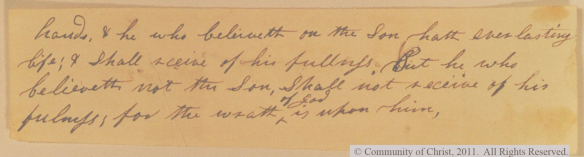

As a witness that the Prophet understood the implication of Jesus’ words to Nicodemus as we have interpreted them here, a note pinned to the nt2 manuscript of the Joseph Smith Translation of the last verse of John 3 reads in part:71

He who believeth on the Son hath everlasting life72 and shall receive of his fulness.

The experiences that allow disciples to “receive of his fulness” extend beyond the initial ordinances of divine rebirth and the accompanying spiritual enlightenment that would allow them to begin to discern the kingdom of God “from the outside,”73 eventually permitting them to see it from within. Consistent with Jesus’ expectation that Nicodemus, as a “master of Israel”74 should have already been familiar with this line of interpretation, there is evidence that “some early Jewish [exegetes] in the more mystic tradition may have also understood ‘seeing God’s kingdom’ in terms of visionary ascents to heaven, witnessing the enthroned King.” Moreover, the Jewish scholar Philo, a near contemporary of Jesus Christ, “declares that the Sinai revelation worked in Moses a second birth which transformed him from an earthly to a heavenly man; Jesus, by [way of] contrast, came from above to begin with and grants others a birth ‘from above.’”75

Some scholars have argued that Philo’s ideas about a “new birth” that transforms earthly man to heavenly man may have been reflected in Jewish ritual at Qumran76 and elsewhere. Such rituals seem to have enacted the liturgical equivalent of actual heavenly ascent.[Page 132]

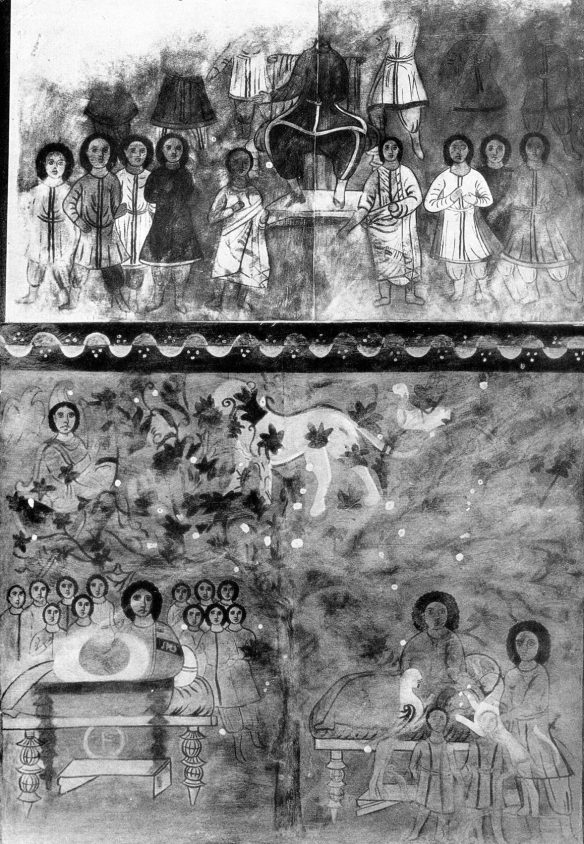

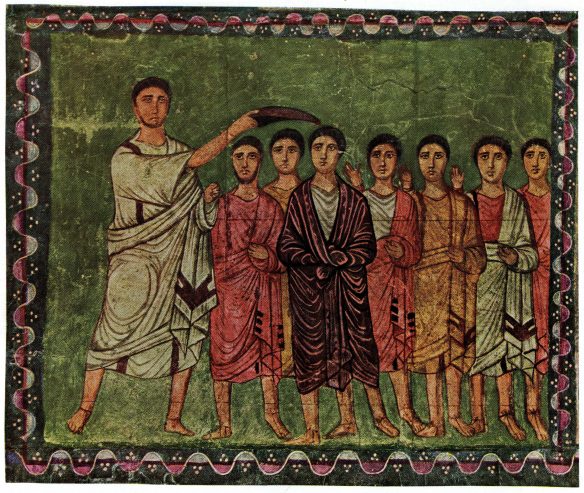

As has been detailed elsewhere in connection with the third-century ad synagogue of Dura Europos,77 one of several plausible narrative foundations for such rituals was the vision of the resurrection of the dry bones in Ezekiel 37. Donald Carson observed that although many Old Testament writers “look forward to a time when God’s ‘spirit’ will be poured out on humankind,”78 the most important of all these is Ezekiel. Carson points out that in Ezekiel 36:25–27, as in John 3, “water and spirit come together so forcefully, the first to signify cleansing from impurity, and the second to depict the transformation of heart that will enable people to follow God wholly. And it is no accident that the account of the valley of dry bones, where Ezekiel preaches and the Spirit brings life to dry bones, follows hard after Ezekiel’s water/spirit passage.”79

The culminating passage of Ezekiel 37, like that of John 3, promises exaltation and eternal life to the faithful. This promise is to be fulfilled through a new and “everlasting covenant.”80 In imagery that parallels chapters 21 and 22 of the book of Revelation, the Lord promises that in the future day of their salvation Israel will be called His people — meaning that they will be called by His name81 — that they will be sanctified, and that His “sanctuary shall be in the midst of them for evermore.”82

Going further, Carson observes that “Israel, the covenant community, was properly called ‘God’s son,’”83 an idea that can be extended not only corporately but also individually, as described, for example, in Psalm 2:7 and Moses 1:4; 6:68. In chapter 16, Ezekiel describes unfaithful Israel as an abandoned female child on whom He had taken pity. When first born, “thy navel was not cut, neither was thou washed in water to supple thee; [Page 133]thou wast not salted at all, nor swaddled at all.”84 However, using the Israelite terminology of adoption and marriage, the Lord relates that He looked upon fledgling Israel with pity, spread His skirt over her to cover her nakedness, and entered into a covenant so that Israel could become His own.85 The passage continues in terminology reminiscent of royal investiture and exaltation, with conceptual roots in the First Temple that will recall for Latter-day Saints the symbolism of modern temples: “Then washed I thee with water; yea, I thoroughly washed away thy blood from thee, and I anointed thee with oil. I clothed thee with broidered work, and shod thee with badger’s skin, and I girded thee about with fine linen, and I covered thee with silk, … And I put … a beautiful crown upon thine head.”86 In reflecting on Jesus’ words, Nicodemus might have recalled prophetic passages like these that describe ritual rebirth in anticipation of the eventual fulfillment of God’s promise to Moses that Israel as a body eventually was to become “a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation.”87

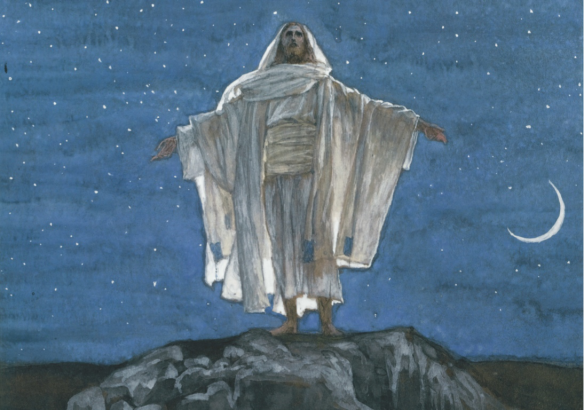

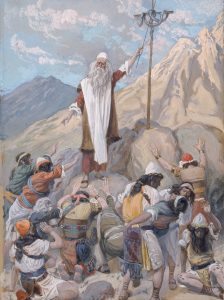

Figure 10. J. James Tissot (1836–1902): Jesus Goes Up Alone unto a Mountain to Pray (detail), 1886–1894.

In summary, a careful reading of John 3, using modern linguistic evidence and considering relevant threads in Jewish scripture and tradition, makes it clear that being “born again” — or, rather, being “born from above” or “born of God”88 — is not a process that is completed when one is baptized by water and receives the gift of the Holy Ghost. Being ritually reborn requires receiving and keeping all the ordinances and covenants of the priesthood89 “to the end.”90 Being fully reborn in actuality happens only after traversing the heavenly veil “to know the [Page 134]only wise and true God, and Jesus Christ, whom he hath sent,”91 having both suffered in His likeness92 and also having been “lifted up” to “eternal life” and exaltation as He was. In other words, to qualify for eternal life, each of the Father’s children must be prepared to enter the kingdom of heaven as a son or daughter of God,93 having first been born again by water and “by the Spirit of God through ordinances,”94 and then, when sanctified, must be received personally by the Father — all this in similitude of their Redeemer, the Son of God,95 their peerless, perfect prototype.96

Having concluded from our study of chapter 3 of the Gospel of John that being born again, in its full sense, describes a process that begins before baptism, when one begins to “see the kingdom of God”97 from “afar off”98 and culminates with “the words of eternal life in this world, and eternal life in the world to come,”99 the remainder of this article will draw out additional, complementary details concerning the process of spiritual rebirth that are available through a close reading of Moses 6:51–68 in light of relevant scripture and prophetic teachings. First, we will provide a brief overview of the setting, structure, and burden of these verses. Then we will conclude with deeper examination of issues and insights relating to the three key phrases of Moses 6:60 one by one: “by the water ye keep the commandment; by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified.”

When discussing temple-related matters, we will follow the model of Hugh W. Nibley, who was, according to his biographer Boyd Jay Petersen, “respectful of the covenants of secrecy safeguarding specific portions of the LDS endowment, usually describing parallels from other cultures without talking specifically about the Mormon ceremony.”100

The Setting, Structure, and Burden of Moses 6:51–68

[Page 135]

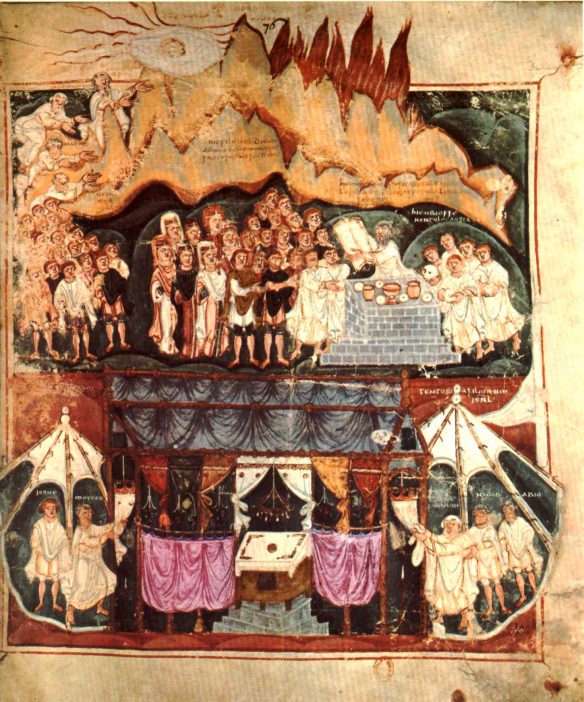

[Page 136]Hugh Nibley describes Moses 6:51–68101 as an “excerpt from the Book of Adam.”102 Perhaps it formed part of the “book of remembrance” mentioned in Moses 6:46. The setting for these verses is a sermon by Enoch. A notation in the handwriting of John Whitmer on the ot1 manuscript above Moses 6:52b reads “The Plan of Salvation.”103 The verses that follow were sometimes cited by early leaders of the Church as evidence for the continuity of the plan of salvation from the time of Adam and Eve to our day.104

Verses 51–68 form a structure of several parts. The introduction (verses 51–52) is a firsthand statement from God the Father wherein He, as the Maker of the world and of men, summarizes the commandments underlying the plan of salvation — namely, to hearken, believe, repent, and be baptized. Then, in verses 53–60, He motivates the commandments one by one in reverse order within a succession of ladder-like rhetorical cascades that culminate in a promise of sanctification through “the blood of [His] Only Begotten.”105

It should be understood that the sure knowledge provided by the “record of heaven”106 that is promised to Adam and Eve and their posterity in verse 61 is more than the prefatory witness that comes to those who have “receive[d] the Holy Ghost.”107 Indeed, elsewhere Joseph Smith equates the “power which records”108 with the sealing power, or, in other words, the power that “binds on earth and binds in heaven.”109 Consistent with this idea, in the ot2 manuscript of Moses 6:61, this “Comforter” is described as “the keys of the kingdom of heaven.”110

In response to God’s explanation of the “plan of salvation,” as it is termed in verse 62, Adam hearkened wihout hesitation to the voice of the Father by obeying the commandments he had been given,111 as outlined in verses 64–65. In return for the witness of Adam’s covenant given in his baptism, he receives the promised “record of heaven,”112 described in more detail in verse 66 as the “record of the Father, and the Son” that was declared through “a voice out of heaven.”113 Having had “all things confirmed unto [him] by an holy ordinance,”114 Adam was “born again into the kingdom of heaven of water, and of the Spirit, and … cleansed by blood,” having become a “son of God”115 in the full sense of the term. Elder Theodore M. Burton’s explanation of the event leaves no room for doubt about the nature of the occurrence described in verse 68:116

Thus Adam was sealed a son of God by the priesthood, and this promise was taught among the fathers from that time forth as a glorious hope to men and women on the earth if they would listen and give heed to these promises.

[Page 137]Relating this event to the sequence of ordinances and blessings that led up to it, Hyrum L. Andrus further explains:117 “To receive such communion, ordinarily one must be justified, sanctified, and sealed by the powers of the Gospel ‘unto eternal life.’”118 In other words, Moses 6:68 witnesses that Adam received “the more sure word of prophecy.”119

After declaring the sonship of Adam, the Father solemnly averred that all the posterity of Adam and Eve, both men and women, must follow the same pattern in order to be born again: “Thus [in other words, by doing as Adam did] may all become my sons.”120

Figure 13. Ron Richmond (1963–): Triplus, Number 3, 2005. The contents of the three bowls symbolize water, blood, and spirit.

Spiritual Rebirth by Water, Spirit, and Blood

Having outlined the meaning and import of Moses 6:51–68 as a whole, we will now examine the interrelated symbolism of water, Spirit, and blood that is highlighted in verse 60. Hugh Nibley summarizes the significance of these three elements as follows:121

The water is an easy act of obedience. … “By the water ye keep the commandment.”122 “I know not, save the Lord commanded me.”123 That’s your sacrifice. Then “by the Spirit ye are justified.”124 That’s the Holy Ghost. … You’ve got to be baptized physically, but then it goes beyond that to the Spirit, where[, after having been confirmed,] you [begin to] understand and [become] aware of what’s going on. … Then [Page 138]the last thing is “and by the blood ye are sanctified.”125 You can’t sanctify yourself but by completely giving up life in this world, which means suffering death, which means the shedding of blood. … [T]he shedding of blood is your final declaration that you are willing to give up this life for the other.

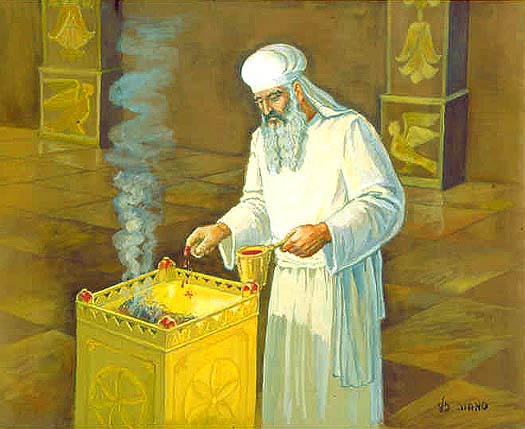

As we will discuss in more detail later on, the temple sacrifices of ancient Israel — which pointed back to Isaac’s arrested sacrifice and pointed forward to Jesus’ unarrested sacrifice — the people were to “see” their own arrested sacrifice and redemption, having been spared the shedding of their own blood through the atonement of Christ. By means of these sacrifices, ancient Israel could be brought to ”see” the Kingdom of God. Likewise, Adam and Eve’s eyes were “opened”126 after their transgression and they “saw” their redemption in the garments of skin that God made for them and also in the sacrifices that He commanded them to make.127 In a similar manner, Latter-day Saints are meant to begin to “see” the Kingdom of God in the sacrament.

“By the Water Ye Keep the Commandment”

Let us now survey six topics that provide some idea of the richness of ancient traditions and modern revelation relating to the water ordinances of baptism and washing.

1. Baptism as a commandment and an introduction to the law of obedience. Baptism by water is often described in scripture as a commandment — both a means to demonstrate obedience to the divine directive to be baptized and also a sign of willingness to keep the law of obedience with respect to all God’s other commandments.128

For example, Nephi described the baptism of the Savior as a witness to His Father “that he would be obedient unto him in keeping his commandments.”129 Alma exhorted the people of Gideon to “enter into a covenant [Page 139]with [God] to keep his commandments, and witness it unto him this day by going into the waters of baptism.”130 And Mormon taught that “baptism is unto repentance to the fulfilling the commandments unto the remission of sins.”131

Significantly, the blessing on the sacrament bread also specifies that those who partake witness in so doing “that they are willing to … keep his commandments.”132 This direct association between the sacramental bread and baptism is reinforced by the pointed omission of a reference to keeping the commandments in the companion blessing on the emblems of the Lord’s blood.133 In addition, only the blessing on the bread mentions that those who partake must be “willing to take upon them the name of [the] Son,134 an initial promise that, as Elder David A. Bednar taught, “clearly contemplates a future event or events and looks forward to the temple”135 for its fulfillment. The distinctive symbolism of the two parts of the sacrament will be addressed later.

Loren Spendlove136 points out that the first meaning of “partake” in Webster’s 1828 Dictionary is: “To take a part, portion or share in common with others; to have a share or part; to participate.”137 He comments: “We all ‘share in common’ or ‘participate’ in the benefits that come from the death and resurrection of Christ (as symbolized by the bread), in that we all will resurrect from the dead.”138 Of course, since we expect to partake in the common benefits of the atonement of Christ, we should expect to partake in the common effort to invite and persuade, by word and example, all men and women to enjoy the full blessings of the gospel of Jesus Christ. This joint participation in the work of salvation is sometimes expressed in the kjv New Testament with the word “fellowship” (Greek koinonia). “Fellowship” describes the intimate relationship between the Savior and His disciples, who must partake of what He suffered in order to partake of His glory.139

With all this in mind, the importance of the commandment for all people to be baptized cannot be overstated.140 However, Joseph Smith taught that unless those who are baptized also have “truly repented of all their sins and … have received of the Spirit of Christ unto the remission of their sins”141 their baptism “is good for nothing,” being of no more use than if “a bag of sand” had been baptized in their place.142

The teachings of the Prophet are a reminder that there is no magic in earthly elements to cleanse us from sin — neither in the water of baptism itself nor, strictly speaking, in the physical act of eating and drinking the emblems of the sacrament.143 As President Brigham Young explained:144

[Page 140]

Will the bread administered in [the] ordinance [of the sacrament] add life to you? Will the wine add life to you? Yes; if you are hungry and faint, it will sustain the natural strength of the body.145 But suppose you have just eaten and drunk till you are full, so as not to require another particle of food to sustain the natural body. … In what consists [then] the benefit we derive from this ordinance? It is in obeying the commands of the Lord. When we obey the commandments of our Heavenly Father, if we have a correct understanding of the ordinances of the House of God, we receive all the promises attached to the obedience rendered to His commandments. …

It is the same in this as it is in the ordinance of baptism for the remission of sins. Has water, in itself, any virtue to wash away sin? Certainly not, … but keeping the commandments of God will [open the way for the atoning blood of Christ to]146 cleanse away the stain of sin.

2. Baptism as the gate to the pathway that leads to eternal life. Latter day Saints know that repentance and baptism are symbolized in scripture as a “gate,”147 the essential access point to the “strait and narrow path which leads to eternal life.”148 In order to eventually enter the Kingdom of God, to which that path leads, each disciple must additionally receive and keep every other law and ordinance of the priesthood “and continue in the path until the end of the day of probation.”149 As Elder Bednar expressed this idea: “Total immersion and saturation with the Savior’s gospel are essential steps in the process of being born again.”150

[Page 141]Associating the gate of baptism with all subsequent laws and ordinances of the Priesthood, Joseph Smith made it clear that baptism was not only a commandment but also a “sign”:151

Baptism is a sign ordained of God, for the believer in Christ to take upon himself in order to enter into the Kingdom of God. … It is a sign of command152 which God hath set for man to enter … [and] those who seek to enter in any other way will seek in vain; for God will not receive them, neither will the angels153 … for they have not obeyed the ordinances, nor attended to the signs which God ordained for man to receive in order to receive a celestial glory. …

There are certain key words and signs belonging to the Priesthood which must be observed in order to obtain the blessing.154 … Had [Cornelius] not taken [these] sign[s or] ordinances upon him … and received the gift of the Holy Ghost, by the laying on of hands, according to the order of God, he could not have healed the sick or commanded an evil spirit to come out of a man, and it obey him;155 for the spirits might say unto him, as they did to the sons of Sceva: “Paul we know and Jesus we know, but who are ye?”156

3. The antiquity of water symbolism in rituals of rebirth. We will not attempt to summarize the varied and controversial histories of the water rituals of purification, penitence, and proselytism in Jewish and Christian traditions.157 Suffice it to say that no credible scholar today doubts that immersion was practiced by Jews for various religious purposes in pre-Christian times, nor would deny that immersion was the standard form of baptism in the early Christian church.[Page 142]

Figure 17. Ancient Mikveh at the Jerusalem Temple Mount, 2011, recalling Oliver Cowdery’s description of the baptismal font as a “liquid grave.”158

Figure 18. The Penitent Baptism of Adam and Eve. 1340–1351. West façade, detail of the upper tympanum, middle archivolt, Church of St. Théobald, Thann, France.

With respect to traditions concerning the antiquity of baptism, we note in passing that not only the book of Moses but also several Islamic, Christian, Mandaean, and Manichaean accounts speak of the baptism of Adam and Eve.159

Some scholars, including Stephen D. Ricks160 and David J. Larsen,161 have argued that the water symbolism of baptism is better understood when it is compared and contrasted with separate rituals in ancient Israel wherein the king was washed and anointed, both prior to his initiation and also at regular renewals of his right to rule.

For example, Larsen writes:162

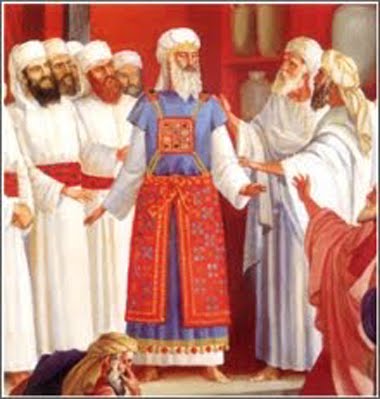

We learn from the Bible that the … king was washed and purified, likely at the spring of Gihon.163 He was anointed on the head with a perfumed olive oil that was kept in a horn in[Page 143]

the sanctuary.164 He was clothed in robes and also wore a priestly apron (ephod165), sash,166 and diadem/headdress.167 Finally, the king was consecrated a priest “after the order of Melchizedek.”168

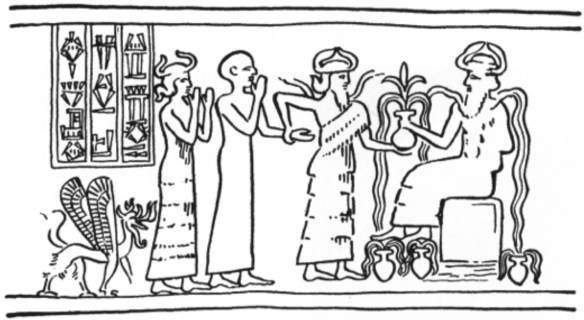

Relevant context for understanding these practices also can be found in the religious literature of ancient Mesopotamia. For example, in the story of Atrahasis we can trace the basic conception that water, spirit, and blood — the latter derived from the body of a slain deity — were the life-giving elements used by the gods in the creation of humankind.169

In the seal of Gudea shown above, the bareheaded and nearly naked Gudea is introduced by a mediating deity to a seated god. The mediating god presents a vase featuring a seedling and flowing water to the seated god. Water flows from the seated god himself into flowing vases, no doubt anticipating the sprouting of seedlings that have yet to appear. The scene suggested is one of rebirth and transformation: drawing on the phraseology of the Gospel of John we might conjecture that having been “born of water,” the king, in likeness both of the sprout within the flowing vase and the god to which he is being introduced, is also to become a “well of water springing up into everlasting life.” A sculpture of Gudea attests to just such an interpretation, where Gudea himself is shown, with his head now covered, holding a vase of flowing water in likeness of the seated god.

A comparative analysis of the full set of rituals of kingship at Mari in Old Babylon and in the Old Testament170 concluded that none of the major themes of Mesopotamian kingship ritual, including the roles that water plays in those rites,171 should be unfamiliar to students of the Bible.[Page 144]

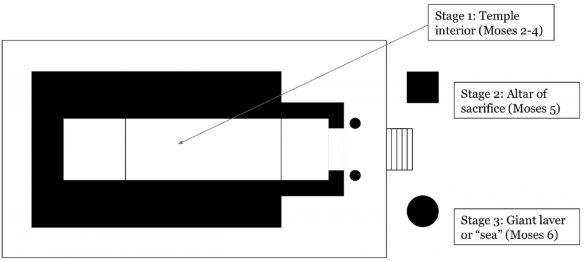

Figure 20. David Calabro: Floor Plan of the Temple of Solomon, with Suggested Locations of the Ritual in Moses 2–6.

Indeed, as John Walton correctly observes, “the ideology of the temple is not noticeably different in Israel than it is in the ancient Near East. The difference is in the God, not in the way the temple functions in relation to the God.”172

David Calabro has explored the possibility that a text with an outline similar to the book of Moses may have been used in Solomon’s Temple to instruct and guide initiates through specific areas where instruction was given and rituals were performed. Of relevance to the present discussion is the connection he suggests between the text of Moses 6 and the “molten sea” that stood in front of the temple.173 After discussing several clues supporting his thesis from the book of Moses, Calabro concludes:

While there is no evidence that the temple laver was used as a baptismal font, it was definitely large enough to suggest such a use, and Joseph Smith’s specifications for a baptismal font modeled after the Solomonic laver for the Nauvoo temple show that he understood it in this connection.

It is evident that two distinct sorts of water ordinances — namely baptism by immersion and washing as part of priestly or kingly initiation — became confused in the first centuries after Christ, making it difficult to know which of which one is meant when Christian scripture or tradition mentions the use of water in religious ritual.174 Indeed, as religious practices evolved, rituals resembling washing, anointing, and clothing were sometimes performed as part of “baptism.”

For example, in some Christian baptismal traditions the idea of “reversing the blows of death” was represented by a special anointing with the “oil of mercy” prior to (or sometimes after) “baptism,”[Page 145]

Figure 21. Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926): The Baptism of Saint Prince Vladimir, 1890. “Attendants hold Vladimir’s golden royal robes, which he has removed, and the simple white baptismal robe, which he will put on.”

as the candidate was signed upon the brow, the nostrils, the breast, the ears, and so forth.175

It was commonly accepted by some Christians that the precedent for such anointings went back to the beginning of time. For instance, in the pseudepigraphal Life of Adam and Eve, we can read an incident where Adam, as he lay on his deathbed, requested Eve and Seth to fetch him oil from the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden so that he could be restored to life.176

[Page 146]

Figure 22. The Quest of Seth for the Oil of Mercy, 1351–1360. Heilig-Kreuz Münster (Holy Cross Minster) in Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany.

Some traditions describe how the baptismal candidate was “stripped of the garments inherited from Adam and vested with the token of those garments he or she shall enjoy at the resurrection.”177 In other traditions, the baptismal candidates “stood [barefoot] on animal skins while they prayed, symbolizing the taking off of the garments of skin they had inherited from Adam” as well as figuratively enacting the putting of the serpent, the representative of death and sin, under one’s heel. Thus the serpent, his head crushed by the heel of the penitent relying on the mercies of Christ’s atonement, was by a single act renounced, defeated, and banished.[Page 147]

4. The context of circumcision in Jesus’ discussion with Nicodemus about being “born again.” A passage from Joseph Smith’s translation of Genesis, discussed in more detail below, highlights the importance of the relationship between baptism as revealed in the beginning to Adam and Eve and the later institution of the Old Testament ordinance of circumcision through God’s command to Abraham. Samuel Zinner describes the relationship between baptism and circumcision as part of the generally underappreciated context for the dialogue of Jesus and Nicodemus about the importance of being “born again”:178

It is perhaps not usually recognized that implicit in John 3’s discussion on the new birth and baptism is the topic of circumcision. Early Christian theology understood baptism as a spiritual circumcision for Gentile adherents of the Jesus sect.179 Rabbinic sources also understand proselyte immersion as a new and spiritual birth. In John 3:4 Jesus’ teaching on rebirth in verse 3 naturally brings circumcision to Nicodemus’ mind, so that in effect he asks, how can a male adult return to the state of infancy and be circumcised again? The (rhetorical) confusion in the discussion arises because Jesus is teaching that a circumcised Jewish male adult must be reborn spiritually. Nicodemus’ thought is that Jewish males are already spiritually reborn from the time of their [Page 148]infant circumcision. Only Gentile proselytes stand in need of spiritual rebirth. In fact, Jesus is referring to John’s baptism of repentance180 for Jews, and Jesus’ imperative, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” alludes to the necessity of John’s baptism of repentance, and forms part of the background of John 3:5’s “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God,” an allusion to John 1:26’s baptism with water and 1:33’s baptism with the Holy Spirit.181 Jesus’ point in John 3 is that Jews need spiritual circumcision in addition to the physical rite, a traditional enough prophetic tanakhic trope.182 In 1QS V we see that spiritual circumcision is demanded in the “community”: “circumcise in the Community the foreskin of his tendency and of his stiff neck” [1QS V 5]. This follows 1QS IV’s teaching on immersion, which matches the pattern established already by Ezekiel183 who speaks of cleansing water followed by the insertion of a new spirit and heart: … [Such] Qumran passage[s], like John the [Baptist’s] and Jesus’ baptismal teachings, [do] not suggest that [baptism] replaces circumcision, but that it complements and perfects it.

5. Circumcision, covenant, and baptism in antiquity and in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible. Consistent with the linkages between circumcision, covenant, and baptism suggested by Zinner are many allusions to these subjects both in antiquity and in Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon and the Bible.

For example, consider Isaiah 48:1 as it is quoted in 1 Nephi 20:1. This gloss (clarifying comment) by Joseph Smith first appeared in the 1840 edition of the Book of Mormon:184

Hearken and hear this, O house of Jacob, who are called by the name of Israel, and are come forth out of the waters of Judah, or out of the waters of baptism, who swear by the name of the Lord, and make mention of the God of Israel, yet they swear not in truth nor in righteousness.

The term “waters” within the phrase “come forth out of the waters of Judah” might be more plainly rendered as “the belly or loins of Judah,” a poetical reference to the literal seed of the body out of which the corporeal descendants of Judah are propagated. For this reason, one might see in this phrase an allusion to the covenant of circumcision, a covenant that was not only made necessary for Abraham[Page 149]

and his biological posterity but also, significantly, something to which all those who had been “adopted” into his household were required to submit.185 Joseph Smith’s gloss — the disjunctive phrase “or out of the waters of baptism” — expands Isaiah’s reference to include Gentiles who could become part of covenant Israel by adoption through proselyte baptism, consistent with 3 Nephi 30:2: “Turn, all ye Gentiles, from your wicked ways; … and come unto me, and be baptized in my name, that ye may receive a remission of your sins, and be filled with the Holy Ghost, that ye may be numbered with my people who are of the house of Israel.”186

An even more pointed reference connecting the themes of circumcision and baptism can be found in the mention of the “blood of Abel” within Joseph Smith’s translation of the book of Genesis. The neglect of this passage by scholars argues for a detailed treatment here.

The story of Abel has always been linked with the idea of proper sacrifice187 — indeed his name seems to be a deliberate pun on the richness of the sacrifice that he will make, in contrast to the stingy offering of Cain:188 “And Abel [hebel], he also brought of the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof” [ûmēḥelĕbēhen — in other words, from the fatlings, the richest or best part of the herd]. Not only does the Hebrew word ḥēleb denote “fat,” but also the word ûmēḥelĕbēhen “contains within itself the name of hbl [Abel] …reversed”— i.e., ûmēḥelĕbēhen, thus strengthening the pun.189

[Page 150]

Figure 27. J. James Tissot (1836–1902): Zacharias Killed Between the Temple and the Altar, ca. 1896–1894.

Remember that in the book of Hebrews, the shedding of Abel’s blood was seen as a type of the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ.190 With respect to his place among the biblical canon of martyrs, Hamilton writes: “Abel is coupled with Zechariah191 as the first192 and the last193 victims of murder mentioned in the Old Testament. … Understandably Abel is characterized as ‘innocent.’”194

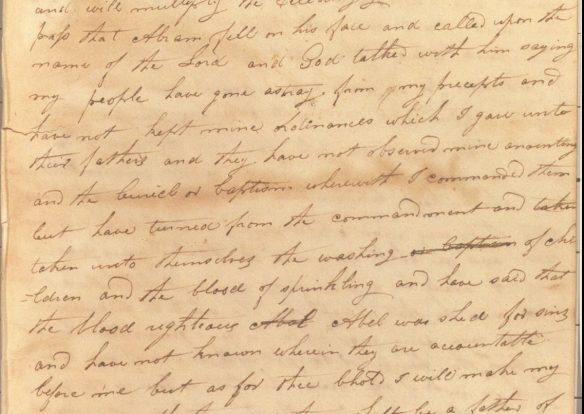

The Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible connects the death of the righteous Abel to an anomalous ordinance for little children consisting of the sprinkling of blood coupled with “washing” that is denounced in jst Genesis 17:3–7:195

[Page 151]And it came to pass, that Abram fell on his face, and called upon the name of the Lord.

And God talked to him, saying, My people have gone astray from my precepts, and have not kept mine ordinances, which I gave unto their fathers;

And they have not observed mine anointing,196 and the burial, or baptism wherewith I commanded them;

But have turned from the commandment, and taken unto themselves the washing or baptism197 of children, and the blood of sprinkling;198

And have said that the blood of the righteous Abel was shed for sins; and have not known wherein they are accountable before me.

To counteract this practice, we are told that the Lord established the covenant of circumcision at the age of eight days,199 “that thou mayest know for ever that children are not accountable before me till [they are] eight years old.”200 D&C 68:25–28, received later in the same year that jst Genesis 17 was translated, also emphasizes that children are not accountable until eight years old.201

[Page 152]

In remarkable resonance with Joseph Smith’s translation, the central figure of Abel is associated with the rituals of water immersion among the Mandaeans.203 Indeed, Abel (often called Hibil Ziwa = Abel Splendor), who is often identified with the roles of redeemer and savior, was said to have performed the first baptism — that of Adam, who prefigures every later Mandaean candidate for these repeated rituals.204

Following the ceremonies of immersion, the Mandaeans still continue ritual practices that include anointing and the pronouncing of the names of the gods upon the individual.205 The kushta, a ceremonial handclasp, is given three times in the ritual, each one of which, according to Elizabeth Drower, “seems to mark the completion … of a stage in a ceremony.”206 At the moment of glorious resurrection, Mandaean scripture records that a final kushta will also take place, albeit in the form of an embrace, called the “key of the kushta of both arms.”207

The concept of an “atoning embrace”208 can be compared with similar imagery in Jacob’s wrestle with the angel209 and his subsequent encounter with Esau;210 in the reconciliation of the father with his prodigal son in Jesus’ parable;211 and especially in the eschatological embraces of Enoch’s Zion and Latter-day Zion described in Moses 7:63: “Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other.”212

[Page 153]

Equally relevant to jst Genesis 17:3–7 is Hebrews 12:24, which speaks of the saints coming “to Jesus the mediator of the new covenant, and to the blood of sprinkling, that speaketh better things than that of Abel.”213 To Craig Koester, this suggests the idea that “Abel’s blood brought a limited atonement, while Jesus’ blood brought complete atonement.”214 With reference to Hebrews 11:4, Joseph Smith said that Abel “holding still the keys of his dispensation … was sent down from heaven unto Paul to minister consoling words, and to commit unto him a knowledge of the mysteries of godliness.”215

The practice of swearing “by the holy blood of Abel” is portrayed in early Christian and Islamic accounts of the efforts of the antediluvian patriarchs to dissuade their posterity from leaving the “holy mountain” to associate with the children of Cain.216 Serge Ruzer interprets this as evidence for the existence of a group that looked to Abel rather than to Christ for salvation. He concludes that the “emphasis here [is] on the salvific quality of Abel’s blood. … Swearing by Abel’s blood … is presented in our text as sufficient for the salvation of the sons of Seth; those who dwell — thanks to swearing by Abel’s blood — on the holy mountain do not need any further salvation.”217

[Page 154]

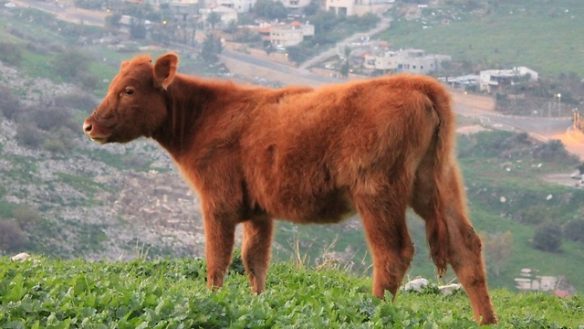

Additional evidence suggesting a belief in salvific power for Abel’s blood comes from a 1 Enoch description of Abel as a “red calf.” Patrick Tiller sees this as an allusion to the red heifer218 of Numbers 19:1 10.219 The great Jewish scholar Maimonides saw the ritual of the red heifer not merely as law of purity, but rather as a matter “of transcendent, even salvific weight and meaning.”220 The red heifer pointedly was a young animal used in purification rites (comprising a washing and a sprinkling of blood221) for those who had come into contact with “one … found slain” and “lying in the field,”222 as was Abel. A widely varying set of Islamic accounts attempt to explain the origin of a related Qur’anic story;223 what these accounts have in common is the idea that the murderer denied his crime but was identified by the voice of the dead man who was touched by the sacrificial animal.224 Could this be an echo of the righteous Abel, of whom scriptures says his “blood cries unto [God] from the ground”225 — wherein “he being dead yet speaketh”?226

In summary, there is ample evidence from a variety of sources dating to at least the Second Temple period to support the plausibility of the account in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible wherein anomalous rituals for little children purporting to cleanse them by washing and the sprinkling of blood are coupled with the erroneous idea that “the blood of the righteous Abel was shed for sins.”227 As a figure associated anciently with sacrifice, baptism, and innocent martyrdom, Abel arguably could have attracted religious notions of this character. Additionally, the rationale for the institution of circumcision in the Joseph Smith [Page 155]Translation is also consistent with Samuel Zinner’s conclusion about the symbolic connection between circumcision and baptism in its New Testament context: namely, that baptism was not meant to replace “circumcision, but [rather] that it complements and perfects it.”228

6. Digression: Baptism and ritual washings as illustrations of the nature of all ordinances. Before concluding our discussion of the symbolism of water in spiritual rebirth, we digress to show how baptism and ritual washings provide a paradigmatic illustration of the nature of all priesthood ordinances. We conclude from our brief discussion of baptism and ritual washings that they, when administered as authentic priesthood ordinances, are symbolic, salvific, interrelated and additive, retrospective, and anticipatory.

- Symbolic. Hugh Nibley defined the endowment as “a model, a presentation in figurative terms.”229 The same can be said for baptism, which Paul described as a symbol of death and resurrection.230 Like the parables of Jesus, the ordinances are meant to provide both an understanding of the spiritual universe in which we live and a model for personal conduct within that context. This is why the Lord condemns in such strong terms those who take their fundamental bearings from other, less perfect “instruments.” Such individuals are described as those who have “strayed from [His] ordinances,” who “seek not the Lord to establish his righteousness” but rather “walk in [their] own way and after the image of [their] own god, whose image is in the likeness of the [telestial, rather than the celestial,] world.”231When our understanding of the universe and our place within it is based on our own warped conceptions instead of the blueprint of the celestial world provided in the ordinances, we will experience the frustration of mistaken ambitions and stunted growth in the personal and social characteristics that matter most in eternity. On the other hand, repeated participation in sacred ordinances over the course of a lifetime allows us to deepen our understanding of “who we are, and who God is, and what our relationship to Him [and to His children] is.”232

- Salvific. President Joseph F. Smith taught:233

I frequently hear people say, “All that is required of a man in this world is to be honest and square,” and that such a man will attain to exaltation and glory. But [Page 156]those who say this do not remember the saying of the Lord, that “except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of [God].”234

While recognizing the superior forms of pedagogy embodied in the symbolism of the ordinances,235 Elder Bednar taught that we err if we think that their value is limited to inspired instruction. He said, citing D&C 84:19–21:236

The ordinances of salvation and exaltation administered in the Lord’s restored Church are far more than rituals or symbolic performances. Rather, they constitute authorized channels through which the blessings and powers of heaven can flow into our individual lives.

In other words, the realization of the promised endowment of knowledge and power promised in the ordinances requires that one be both informed and transformed.237 Indeed, the blessing of being “born again by the Spirit of God through ordinances,”238 in conjunction with the strengthening power of the atonement of Christ, is obtained only as individuals live for it — in a continual effort of obedience and service that strengthens the ties of covenant with which they are freely and lovingly bound to their Heavenly Father.239 Only by both understanding and conforming to the divine pattern given in the ordinances may individuals gradually experience an increasing measure of the joy of becoming all that God now is.

- Interrelated and additive. Elder Bednar explained:240

The ordinances of baptism by immersion, the laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Ghost, and the sacrament are not isolated and discrete events; rather, they are elements in an interrelated and additive pattern of redemptive progress. Each successive ordinance elevates and enlarges our spiritual purpose, desire, and performance. The Father’s plan, the Savior’s Atonement, and the ordinances of the Gospel provide the grace we need to press forward and progress line upon line and precept upon precept toward our eternal destiny.

That the ordinances must be closely interrelated should be obvious — after all, each one is based on the same doctrine of Christ. Illustrating this point, Elder Bruce R. McConkie noted that three different ordinances — baptism, the sacrament, and [Page 157]animal sacrifice — were instituted at different times, are enacted using different symbolism, and are employed in different settings, however all are performed in association with one and the same covenant.241 In other words, although each of these three ordinances fulfills a unique purpose and varies somewhat in what it signifies, all are “performed in similitude of the atoning sacrifice by which salvation comes.”242 As an aside, we note in this connection that any adaptation of an ordinance to different times, cultures, and practical circumstances must be made by proper authority in order to minimize the possibility of changes that may alter it in crucial ways.

It is likewise essential that the ordinances be additive. For example, just as baptism must be preceded by faith in Jesus Christ and sincere repentance,243 so the ongoing process of sanctification — made available to those who are confirmed, receive, and retain the gift of the Holy Ghost — can come only to those who have been prepared previously through baptism. Likewise, the initial budding of “the power of godliness” that is increasingly “manifest”244 in the lives of faithful members of the Church as they renew their prior covenants through the sacrament prepares them for the additional ordinances and covenants they will later receive in the temple.

Further illustrating the additive nature of the ordinances, we note that faith, hope, and charity served anciently both as symbols of the three degrees of glory represented in the temple and also as stages in the disciple’s earthly experience marked by progression in the ordinances and the keeping of covenants. This same triad was represented both anciently and in the teachings, translations, and revelations of Joseph Smith as a ladder of heavenly ascent that must be mounted rung by rung.245

[Page 158]Elder Bednar’s characterization of the “additive pattern of redemptive progress”246 suggests that those who are striving to become saints are passionate, not passive, about their discipleship. Like Abraham,247 they are driven by “divine discontent,”248 not being satisfied with the sort of minimal, negative obedience which requires only that they avoid the “appearance of sin,”249 but rather, seeking to be “anxiously engaged”250 in furthering the Father’s work with “all [their] heart, might, mind and strength.”251 By this means, they eventually become capable of enduring all things, being filled with perfect faith, hope, and charity, their will “being swallowed up in the will of the Father”252 to the point that, after a lifetime of faithfulness to every covenant they have received and through the strengthening power of the Atonement, they begin to approach the “measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ.”253

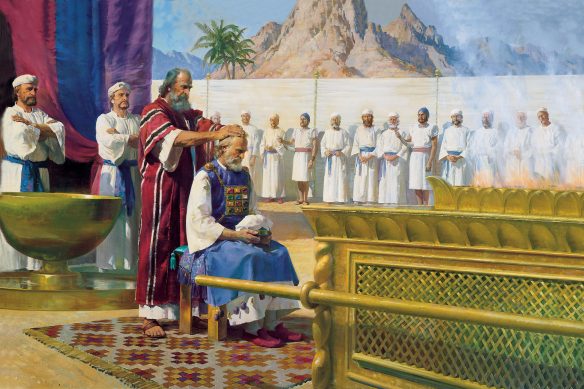

- Retrospective. An appreciation of the retrospective regard of the ordinances clears up any confusion about the relationship between baptism and other water ordinances.254 Since the time of Adam, baptism has been the first,255 introductory256 saving ordinance of the Gospel given in mortal life, and any similarities between baptism and later ordinances of washing are meant to highlight and build upon that resemblance retrospectively.Further illustrating the retrospective regard of later washing ordinances, we would suggest that their significance harks back before baptism, echoing earlier events that occurred in the premortal life. For example, it appears that the ordinance received[Page 159]

by Aaron when he was “wash[ed],” “anoint[ed],” and clothed in “holy garments … so that he [might] minister unto [the Lord] in the priest’s office”257 recapitulated his foreordination to this priesthood calling when he was “wash’d and set apart”258 in the premortal world. Consistent with the teachings of Joseph Smith,259 Alma 13 states that “[high] priests were ordained after the order of [God’s] Son, … being called and prepared from the foundation of the world … with that holy calling … according to a preparatory redemption for such.”260 Similarly, President Spencer W. Kimball taught that in premortal life, faithful women were also given assignments to be carried out later on earth.261

Speaking of Christ as the premortal prototype for all those who were foreordained to priestly offices and subsequently ordained in mortal life, the Gospel of Philip suggests that the general meaning, symbolism, and sequence of the ordinances has always been the same: “He who … [was begotten] before everything was begotten anew [i.e., “by the water”262]. He [who was] once [anointed] was anointed anew [i.e., “by the Spirit”263]. He who was redeemed in turn redeemed (others) [i.e., “by the blood”264].”265

- Anticipatory. [Page 160]Because the round of eternity266 is embedded in the ordinances, we would expect them not only to be retrospective but also anticipatory in nature. For example, in Moses 5 Adam learns that the ordinance of animal sacrifice was instituted in explicit anticipation of the sacrifice “of the Only Begotten of the Father”267 — just as, of course, the ordinance of the sacrament looks back retrospectively on that same expiatory sacrifice. With regard to the sacrifice of Isaac, Hugh Nibley asked:

Is it surprising that the sacrifice of Isaac looked both forward and back, as “Isaac thought of himself as the type of offerings to come, while Abraham thought of himself as atoning for the guilt of Adam,” or that “as Isaac was being bound on the altar, the spirit of Adam, the first man, was being bound with him”?268 It was natural for Christians to view the sacrifice of Isaac as a type of the crucifixion, yet it is the Jewish sources that comment most impressively on the sacrifice of the Son. When at the creation of the world angels asked, “What is man that You should remember him?”269 God replied: “You shall see a father slay his son, and the son consenting to be slain, to sanctify My Name.”270

In this regard, we note that Abraham is unique in scripture in that he came to understand Christ’s atonement both from the perspective of a father271 and also from that of a son.272

As another example of the anticipatory nature of the ordinances, recall the witness of jst Genesis 17:11 that the divine introduction of circumcision in the time of Abraham, somewhat like the ordinance of naming and blessing of little children in our day, was important not only in its own right, but also because it pointed forward to the ordinance of baptism. Remember that a primary reason for the institution of the practice of circumcision was “that thou mayest know for ever that children are not accountable before me till [they are] eight years old.”273 The blood shed in circumcision, whose mark remained in the child as a permanent “sign” in the flesh,274 could be understood as a symbol of arrested sacrifice275 that invited retrospective reflection on the universal salvation of little children through the blood of Christ’s atonement. At the same time, the symbolism of[Page 161]circumcision also implicitly facilitated a correct, anticipatory understanding of the necessity of justification accomplished through “the Spirit of Christ unto the remission of their sins”276 that was meant to accompany the baptism of children when they reach the age of accountability.

Note also that the symbolism of death and resurrection in the ordinance of baptism anticipates the instruction and covenants of the temple endowment that further detail the responsibilities and blessings of those who will pass through the veil to rise in the first resurrection.277 Similarly, the initiatory ordinance of washing, anointing, and clothing278 provides an anticipatory, capsule summary of all the ordinances. More specifically, one might conclude that the structure of the initiatory ordinance of the temple reflects the threefold symbolism of water, spirit, and blood found in Moses 6, thus outlining the path of exaltation that is further elaborated in the endowment. In addition, the anticipatory nature of the initiatory ordinance is captured in Truman G. Madsen’s description of it as “a patriarchal blessing to every organ and attribute and power of our being, a blessing that is to be fulfilled in this world and the next.”279[Page 162]

Going further — and consistent with the idea that the temple is a model or analog rather than an actual picture of reality — Elder John A. Widtsoe taught that the essential earthly ordinances anticipate or, perhaps more precisely, prefigure heavenly ordinances in which eternal truths and blessings will be taught and bestowed in a more perfect and finished form:280

Great eternal truths make up the Gospel plan. All regulations for man’s earthly guidance have their eternal spiritual counterparts. The earthly ordinances of the Gospel are themselves only reflections of heavenly ordinances. For instance, baptism, the gift of the Holy Ghost, and temple work are merely earthly symbols of realities that prevail throughout the universe; but they are symbols of truths that must be recognized if the Great Plan is to be fulfilled. The acceptance of these earthly symbols is part and parcel of correct earth life, but being earthly symbols they are distinctly of the earth and cannot be accepted elsewhere than on earth. [Page 163]In order that absolute fairness may prevail and eternal justice may be satisfied, all men. to attain the fulness of their joy, must accept these earthly ordinances. There is no water baptism in the next estate nor any conferring of the gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of earthly hands. The equivalents of these ordinances prevail no doubt in every estate, but only as they are given on this earth can they be made to aid, in their onward progress, those who have dwelt on earth.

The distinction between earthly and heavenly ordinances is perfectly expressed in the ot1 manuscript version of Moses 6:59. It is true that the first part of the verse might seem to imply that the culminating earthly ordinances, whose cleansing power is provided by “the blood of mine Only Begotten,” provide a complete initiation “into the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven” in this life. However, the verse closes by making a distinction between the “words of eternal life” — meaning both the revelations of the Holy Spirit with regard to temple ordinances and, ultimately, the sure promise of exaltation that can only be received in an anticipatory way “in this world” — and “eternal life” itself, which can only be granted “in the world to come.”281

By way of summary, we might say that the ordinances associated with water, spirit and blood are saturated with symbolism. Indeed, Elder John A. Widtsoe specifically described the endowment as being “so packed full of revelations … that no human words can explain or make [them] clear.”282 More specifically, we might say that the ordinances are overloaded with a superabundant profusion of meanings, overdetermined in the tangible forms that they take, and deliberately overlaid in successive refinement so as to facilitate incremental growth of understanding and practical application in the lives of those who receive them. Like the cruse of oil blessed by Elijah and the inexhaustible pitcher of Baucis and Philemon, study of and participation in the ordinances will continually pour out new depths of meaning to those who are spiritually prepared to receive them.283

As the joint purport of the ordinances is gradually revealed to faithful disciples, they begin to see how their several meanings function as keys to the dense conceptual and practical nexus at the heart of the Gospel; reverberating in harmony throughout the parallel yet interwoven conceptual realms of doctrines, ordinances, and covenants; and ultimately, in their transformative power, unlocking the “power of godliness”284 that constitutes the supreme significance and purpose of Creation.[Page 164]

Figure 37. Unfurling Heart-Shaped Fern Frond, a Symbol of New Life in the Maori Culture (Koru) and a Manifestation of the Fibonacci Sequence in Nature.

Both in their additive auto-resemblance and in their Janus-like anticipatory and retrospective regard, the fractal nature of the ordinances is made apparent, with the beauty of their self-similar patterns becoming even more impressive under bright light and increasingly closer examination. There is glory in the details.

“By the Spirit Ye Are Justified”

Now we turn our attention to the second phrase in Moses 6:60: “by the Spirit ye are justified.” As in the previous discussion of the water ordinances of baptism and washings, the symbolic, salvific, interrelated, additive, retrospective, and anticipatory nature of the ordinances of spiritual rebirth associated with the Spirit will become apparent.

Before delving deeper into this subject, we will discuss four fundamental questions about justification and sanctification:

1. What does it mean to be justified? [Page 165]Simply put, individuals become “just” — in other words, innocent before God and ready for a covenant relationship with Him — when they demonstrate sufficient repentance to qualify for an “initial cleansing from sin”285 “by the Spirit,”286 thus having had the demands of justice satisfied on their behalf through the Savior’s atoning blood.287

2. But don’t the scriptures refer specifically to “baptism for the remission of sins”?288 Because “baptism” and “remission of sins”289 occur together so often in telescoped scripture references, the role of the Spirit as the agent for the process of justification is easily forgotten. However, a survey of scripture will reveal that “remission of sins” is mentioned most frequently in verses that omit any mention of baptism. In these and other references, remission of sins is typically coupled with the preparatory principles of faith or repentance rather than with the ordinance of baptism itself.290

Although baptism by proper authority is a commandment that must be strictly observed to meet the divine requirement for entrance into the kingdom of God, it is but the necessary, outward sign of one’s willingness to take upon oneself the name of Jesus Christ and keep His commandments. A significant phrase in D&C 20:37 explains with precision that it is not the performance of the baptismal ordinance that cleanses, but rather the individuals’ having “truly manifest[ed] by their works that they have received of the Spirit of Christ unto a remission of their sins” — a requirement that, according to this verse, is clearly intended to precede water baptism.291 In other words, strictly speaking, it is not baptism but rather the fact of having “received of the Spirit of Christ” as the result of faith and repentance that is responsible for the mighty “change of state” wherewith individuals are “wrought upon and cleansed by the power of the Holy Ghost”292 — for “by the Spirit ye are justified.”293

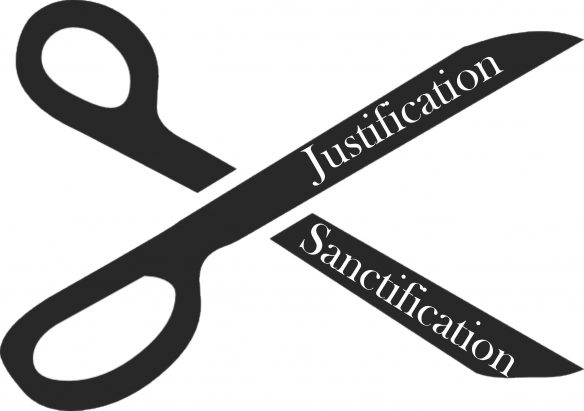

3. How do the ongoing processes of justification and sanctification complement and sustain one another? To adapt imagery from C. S. Lewis,294 it might be said that the interwoven processes of justification and sanctification are as complementary and mutually necessary as the two blades of a pair of scissors. Just as the Spirit of Christ should be received prior to baptism so that individuals may receive an initial, justificatory remission of sins, so the Holy Ghost should be received and cherished after baptism and confirmation, so that individuals may benefit from the availability of its constant,295 ongoing296 sanctifying influence.[Page 166]

Without justification, the sanctifying “companionship and power of the Holy Ghost”297 are not operative. For just as “no unclean thing can dwell … in [God’s] presence,”298 so the “Holy Ghost [cannot] dwell in”299 unclean individuals.300 And without sanctification, those who have been made clean through the justifying Spirit of Christ could never gain access to the strengthening power that will enable them “to keep the commandments of God and grow in holiness.”301

The “companionship and power of the Holy Ghost”302 are available for the ongoing work of sanctification only so long as individuals live worthy to maintain its presence. When those on the path of sanctification fail to keep the commandments, they must repent and be made clean again before they can continue their onward growth along the path of sanctification. In this fashion, the complementary processes of justification (remission of sins) and sanctification (the gradual changing of one’s nature that allows individuals to become “new creatures”303 in Christ) may operate, if we so choose, throughout our lives, preparing us eventually to be spiritually reborn in the ultimate sense.304

Aided by repeated preparation for and participation in the ordinance of the sacrament, we can “always retain [a justificatory] remission of our sins”305 and we can “always have the Spirit of the Lord to be with us”306 for the ongoing work of sanctification.[Page 167]

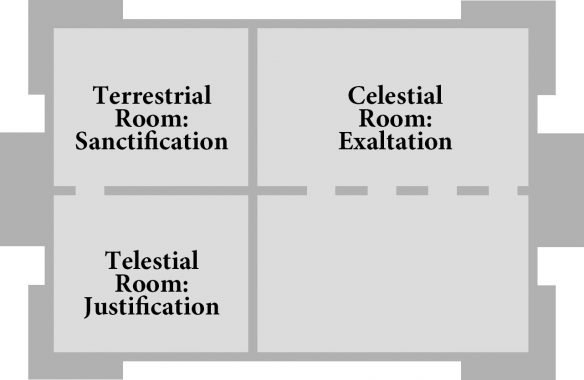

This figure superposes the sequence of justification, sanctification, and exaltation upon the layout of ordinance rooms on the second floor of the Salt Lake Temple. It is meant to illustrate how justification and sanctification can be seen from a different but equally valid perspective as sequential steps instead of as interwoven parts of a parallel process.307 Justification and sanctification, the two initial steps of this sequence, are described in imagery from King Benjamin’s speech. He exhorts his people, first, to “[put] off the natural man” (without which one cannot be “clothed upon with robes of righteousness”308) and, second, for each to “become a saint,” “willing to submit to all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon him.” He emphasizes that this fundamental transformation, by which a “natural man” may become a “saint” if he so chooses, is made possible “through the atonement of Christ the Lord.”309

From this perspective, we might consider the initial remission of sins through the Spirit, the ordinance of baptism (distinct from washing, yet related to it through the use of water), and the receiving of the gift of the Holy Ghost after confirmation as accomplishing the first step of justification, by which we “put off the natural man.”310 Through their continued faith311 in Jesus Christ and faithfulness312 in keeping the commandments, individuals living in a telestial world may progress to a point where they can be “quickened by a portion of the terrestrial glory.”313

[Page 168]In the process of sanctification associated with progress of a terrestrial nature, individuals may become “saints”314 in very deed. Having been “quickened by a portion of the terrestrial glory,” they continue to “receive of the same” unto “a fulness”315 through additional ordinances and the ongoing, sanctifying anointing,316 as it were, of the Spirit of the Lord. Finally — having received a “fulness” of the terrestrial glory, having experienced a “perfect brightness of hope”317 (as described by Nephi), “a more excellent hope”318 (as described by Mormon), or “the full assurance of hope”319 (as described by Paul),320 and having demonstrated their capacity for supreme self-sacrifice as required by the law of consecration, and being filled with “charity[,] … the pure love of Christ,”321 — these individuals can be “sealed up unto eternal life, by revelation and the spirit of prophecy, through the power of the Holy Priesthood.”322 In this manner, they are sanctified by the blood, “quickened by a portion of the celestial glory”323 and made ready to “behold the face of God.”324

In the process of exaltation, individuals who have been previously “cleansed by blood, even the blood of [the] Only Begotten; that [they] might be sanctified from all sin”325 may then go on to receive additional blessings in the celestial world, being “crowned with honor, … glory, … immortality,”326 and “eternal lives.”327 The Lord declared that these individuals shall be “clothed upon, even as I am, to be one with me, that we may be one.”328

4. Do justification and sanctification come by the Spirit or through the Savior? Justification and sanctification are accomplished through the constant companionship of the Holy Ghost329 and, at the same time, made possible through the atonement of Christ. Therefore, it is no contradiction when scripture testifies both that we are “sanctified by the reception of the Holy Ghost”330 and also that it is “by the blood [we] are sanctified.”331 D&C 20:30–31 states that both “justification” and “sanctification” come “through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”332

Confirmation, Anointing, and the Sanctifying Influence of the Holy Ghost. Specific gestures have been divinely prescribed for the ordinance of confirmation and for subsequent ordinances of anointing. While the form of baptism recalls the symbolism of death and resurrection, the laying of hands on the head333 that is used in confirmation suggests a retrospective regard toward the scriptural account of the creation of Adam wherein God “breathed into his nostrils[Page 169]

the breath of life.”334 In this respect, recall also the account in John 20:22, when Jesus “breathed on [His disciples], and saith unto them, Receive ye the Holy Ghost.” As Joseph Smith highlighted the importance of the manner in which baptism is performed, describing it as a “sign,” so did he refer to the symbolic evocation of the breath of life in “the laying on of hands,” by which the Holy Ghost is given, ordinations are performed, and the sick are healed, as a “sign.” He said pointedly that if such ordinances were not performed in the way God had appointed they “would fail.”335

In this context, we might recall what Jesus said when Peter wanted him to wash his head and hands in addition to his feet: “He that is washed needeth not save to wash his feet, but is clean every whit.”336 The Lord’s reply to Peter suggests why, in similar fashion, the laying of hands on the head within various ordinances equates to a blessing for the entire body.

With regard to ordinances of anointing that are associated with the sanctifying influence of the Holy Ghost, biblical and Egyptian sources associate the receiving of “divine breath” not merely with an infusion of life, but also with royal status.337 For example, Isaiah attributes the presence of the Spirit of the Lord to a prior messianic anointing — the anointing oil, like divine breath, being a symbol of new life: “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath anointed me.”338

[Page 170]

Anointing followed by an outpouring of the Spirit is documented as part of the rites of kingship in ancient Israel, as when Samuel anointed David “and the Spirit of the Lord came upon David from that day forward.”339

Note that in Israelite practice, as witnessed in the examples of David and Solomon, the moment when the individual was made king would not necessarily have been the time of his first anointing. The culminating anointing of the king corresponding to his definite investiture was sometimes preceded by a prior princely anointing. LeGrand Baker and Stephen Ricks describe “several incidents in the Old Testament where a prince was first anointed to become king, and later, after he had proven himself, was anointed again — this time as actual king.”340 Modern Latter-day Saints can compare this idea to the conditional promises they receive in association with ordinances and blessings, which are to be realized only through their continued faithfulness. Further emphasizing the anticipatory nature of this ordinance, Brigham Young explained that “a person may be anointed king and priest long before he receives his kingdom.”341

[Page 171]

Figure 42. Queen Elizabeth II, Dressed in White Linen, Is “Screened from the General View” in Preparation for Her Anointing.