[Page 1]Abstract: Joseph Smith made various refining changes to the Book of Mormon text, most of them minor and grammatical in nature. However, one type of textual change has been virtually unstudied in Book of Mormon scholarship: extemporaneous change that was present the moment Smith dictated the original text to his scribes. This type of change appears to have been improvisational, a fix or repair made in the middle of a thought or expression. I study these improvisations in depth — where they might appear historically, their purpose, and their authorship — in two articles. The evidence points to ancient authors and editor-engravers whose extemporaneous changes appeared during the early layers of the Book of Mormon’s construction. In this paper, Article One, we study the improvisations found in the quoted ancient texts of ancient prophets, then in the embedded texts of authors who improvise, and finally in the improvisational narratives of the major editor-engravers — Mormon, Nephi, and Moroni. The findings tell us much about the Book of Mormon as scripture, and about the construction and compilation of scripture by ancient editors and authors.

Introduction

Over the 15 years of his life after completing translation of the Book of Mormon in 1829, Joseph Smith returned to its text to make minor refinements. “In his editing for the 1837 and 1840 editions, he made several thousand changes, virtually all grammatical or stylistic in nature, [Page 2]in an attempt to modernize the language,” said Grant Hardy.1 According to Royal Skousen: “[T]he second edition, published in Kirtland, Ohio … shows major editing by Joseph Smith towards standard English,” and “the third edition, published in Nauvoo, Illinois … shows minor editing by Joseph Smith (including a few restored phrases from the original manuscript).”2 Skousen provides a list of 719 important changes in the Book of Mormon across all editions to the present day; simple inspection shows them to be minor grammatical changes.3

However, another type of textual change has been virtually unstudied in Book of Mormon scholarship: extemporaneous change that was present the moment Joseph Smith dictated the original text to his scribes. This type of change appears to be improvisational in nature, not planned or thought through in advance, a fix or repair made in the middle of a thought or expression. (I use the terms extemporaneous change and improvisation interchangeably.) I have studied these native changes in depth, contextually where they appear in the Book of Mormon narratives, temporally how they are treated over time and across editions, and serially when they appear in the overall translation process. I am interested in why they appear, what was their purpose, and who wrote them.

These improvisations are important because they enable us to explore the composition, design, and construction of the Book of Mormon at a deep and elemental level using the corrective tools that all authors use. Their usage patterns — the types of improvisations used and the contexts in which they are used — become identifiers of the patterns of authorship of the various texts and narratives within the broader complete work. Were the improvisations we see the work of many authors, a few authors, or one single author? Is there evidence that they are either ancient or modern in origin?

Remarkably, Smith virtually never modified these extemporaneous changes in subsequent Book of Mormon editions — even though one would have expected him to change them. Many of these improvisations include seemingly obvious errors, while others appear as clearly awkward or clumsy expressions to a modern reader. He must have noticed at least some of these in his later proofreading; he made minor single-word grammatical changes in only a few but otherwise left the entire sample of these inelegant improvisations untouched. Why were they treated so deferentially, preserved virtually intact across manuscript and print editions prepared under the prophet’s supervision? Amidst a proclivity to make “thousands” of minor grammatical changes, his persistent [Page 3]inclination to retain these inelegant improvisations is a paradox we need to understand.

Conjunctions and Corrective Conjunction Phrases

One of the essential skills of an orator, writer, editor, or translator is the ability to readily make textual corrections and alterations while composing a text to ensure that the author’s original intent is adequately conveyed in the final written or spoken word. One such tool is the use of conjunctions to append or stitch together sentence phrases or sometimes complete and complex sentences that correct, fix, or modify what was just spoken or written — a spontaneous correction made “on the fly.” I call these corrective conjunction phrases (CCPs).4 I have identified 170 CCPs in the Book of Mormon.5 Orators and writers use corrective conjunctions all the time to correct or clarify, often while speaking extemporaneously, to achieve greater precision in the point they want to make. For example, in September 1859, during the American presidential Lincoln-Douglas debates, Abraham Lincoln said to an audience in Columbus, Ohio, “In 1784, I believe, this same Mr. [Thomas] Jefferson drew up an ordinance for the government of the country upon which we now stand, or, rather a frame or draft of an ordinance for the government of this country.”6 After articulating his initial thought (underscored) Lincoln used a corrective conjunction (bolded) to convey a corrected rendition (italicized). Brigham Young, speaking during a discourse on the Sabbath in the Tabernacle in Ogden City, June 4, 1871, said, “This is as simple as anything can be, and yet it is one of the hardest things to get people to understand, or rather to practice; for you may get them to understand it, but the great difficulty is to get them to practice it.”7 Similar to Lincoln, Young used a corrective conjunction to correct and then amplify on his intended point.

Brant Gardner suggests that extemporaneous change was especially typical of cultural settings reliant primarily on oral communication in which written texts were designed mostly as a support — evident in the records seen in Book of Mormon cultures:

What we have in the Book of Mormon is representative of extemporaneous self-correction. … When it occurs, it occurs just as it would in spontaneous speech and I suggest that it is an artifact of the oral style that is [then] replicated in writing precisely because the oral style informs the literary. It becomes pseudo-spontaneity only in literature that is subject to revision and editing before being committed to final written form. … [Page 4][S]elf-correction in the Book of Mormon is an indication that there was some spontaneous writing on the plates.8

An Example of Extemporaneous Change

CCPs are usually constructed out of two thought expressions or ideas that are connected by a conjunction such as “or,” or hybrid conjunctions such as “or rather,” “or in other words,” “or in fine,” or similar variations. To illustrate, let us look at the editorial improvisations of one Book of Mormon editor-engraver, Mormon, with an excerpt from the book of Alma as the sons of Mosiah prepare to embark on separate missions to the Lamanites. The text describes Ammon’s leadership role among them as follows:9

Now Ammon being the chief among them,

or rather he did administer unto them,

he departed from them,

after having blessed them according to their several stations,

having imparted the word of God unto them,

or administered unto them before his departure.

And thus they took their several journeys throughout the land.

Earliest Text,10 340, Alma 17:18

The passage is difficult to follow, but note carefully how its complete meaning gets constructed through improvisation. The phrase at the beginning of the account, Ammon being the chief among them, is important but ambiguous, triggering an improvisational clarification (italicized, lines 2–5), signaled by “or rather.” Note that being chief among them, as clarified, has a decidedly sacred meaning — administering, blessing, and imparting the word of God. But pause to clarify yet again, signaled by another corrective conjunction “or.” What is most important (clarified and stressed a second time) is that Ammon administered unto them before his departure — as in administer a sacrament, according to Noah Webster11 — suggesting a ritual act of blessing, giving, or bestowing by administration on Ammon’s missionary companions.

In sum, this text in Mormon’s work constructs through improvisation — though not necessarily eloquently or elegantly — what it means to be chief among them, including teaching, blessing, imparting the word of God, and most important, administering by dispensing or bestowing sacramentally a sacred consecration to teach the word of God in their [Page 5]forthcoming missionary stations. Note too that the passage betrays Mormon’s distinctive persona as a military commander, documented in the later book of Mormon: “chief among them” is noticeably a military metaphor relating to rank, leadership, and command, which therefore evokes the improvisation we see needed to adapt the metaphor to this sacred setting.

After studying this extemporaneous passage, the reader comes away with a richer appreciation of what Mormon apparently wants to convey, even though patching and improvisation are required to bring it about. Most readers never notice such a passage and take it for granted. Yet closer inspection reveals an improvisation that is a work of considerable effort and authentic accomplishment for the author despite its imperfections; it lets us peer into his mind to see his creative impulse in this challenging but important authorial situation, important enough here to interrupt his writing to clarify two times. Most of all, this improvisation is original to this author, an authentic and inimitable expression as a writer and editor, etched into the recorded pages of his history. Improvisations are jewels of ingenuity, dexterity, and resourcefulness; they reveal nuances, subtleties, and character — like Leonardo da Vinci’s personal notes written using mirror writing because Leonardo was left-handed and mirror writing came easily to him, preserved today as authentic portals into the mind of a brilliant artist and composer.12

Research Design

It is sometimes difficult to know precisely who inserted the corrective conjunction phrase into a passage; whether Smith did while translating in the nineteenth century; whether the engravers of the actual plate text did, such as Mormon, Nephi, or Moroni;13 or whether even earlier authors or orators did, those whose words are quoted or embedded by the engravers, such as Alma, Abinadi, Limhi, or Benjamin. We should expect that the improvisations of different authors or editor-engravers will be manifest in different extemporaneous change patterns. Alternatively, if the improvisations of the entire Book of Mormon corpus are the product of one person — such as Joseph Smith, or possibly Moroni, as composite contributors of the overall text — then there should appear a predictable pattern consistent with that of one solo contributor rather than many smaller co-contributors. These are alternative hypotheses that we will explore, the first in this paper, Article One, and the second in Article Two.

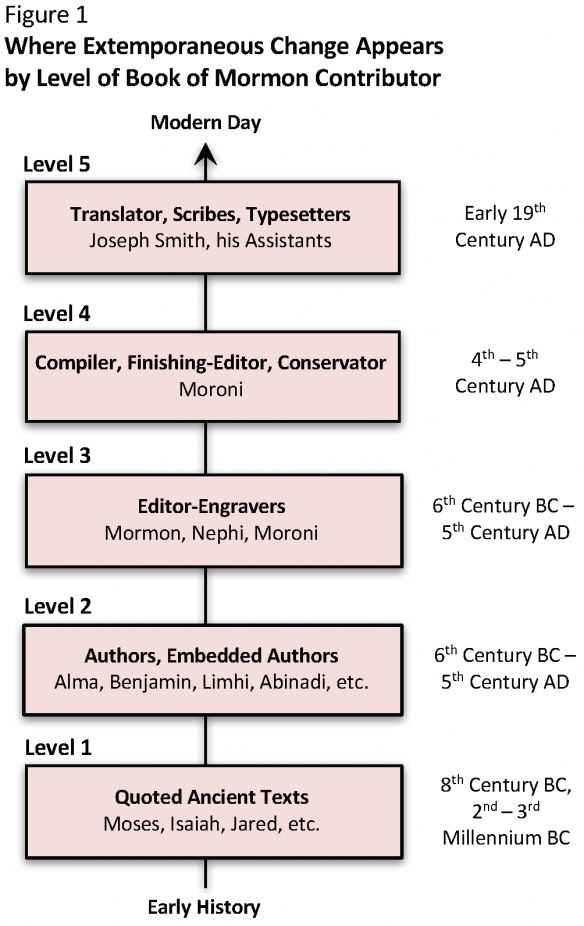

[Page 6]I organize my research into layers or strata, similar to an archeological dig (see Figure 1), starting with the improvisations discovered in the deepest layers of the Book of Mormon’s literary construction, and then move up level by level. We will study:

- Extemporaneous Changes of Quoted Ancient Texts (Level 1), those found in the ancient writings of seminal prophets such as Moses or Isaiah who are quoted by later authors and editor-engravers.

- Authors’ Extemporaneous Changes (Level 2), those improvisations appearing in the embedded author texts of Nephite and Lamanite [Page 7]authors such as Alma, Benjamin, Jacob, Limhi, Abinadi, Samuel, and others.

- Editor-Engravers’ Extemporaneous Changes (Level 3), from the three major editor-engravers Mormon, Nephi, and Moroni, who improvise while designing, constructing, composing, and editing the book’s narratives.

- Extemporaneous Changes of the Compiler, Finishing-Editor, and Conservator (Level 4), from Moroni, apparently acting alone, who compiled and proofread the entire Book of Mormon codex, and whose fingers made the last impressions on the ancient plates.

- Extemporaneous Changes of the Translator, Scribes, and Typesetter (Level 5), from Joseph Smith and his assistants, whose improvisation appears during the modern period of translation and publication, visible across successive manuscript editions of the Book of Mormon from 1829 to 1840.

We will explore these layers in two sequential articles. This paper, Article One, studies the improvisations of the authors and engravers of the Book of Mormon (Levels 1–3 of Figure 1), with a more statistical focus. Article Two studies the improvisations of Moroni and Joseph Smith, particularly in their roles as final contributors to the complete work as presented in the modern day (Levels 4–5). Article Two especially explores how extemporaneous changes are constructed, providing a way to judge the historical composition of these improvisations, whether ancient or modern. I conclude with a discussion of why these findings are significant and what the improvisational patterns and constructions enable us to infer about the Book of Mormon as an apparent collection of ancient texts, and about the meaning, makeup, and character of ancient scripture as presented by Smith to the modern world.

Extemporaneous Change in the Book of Mormon

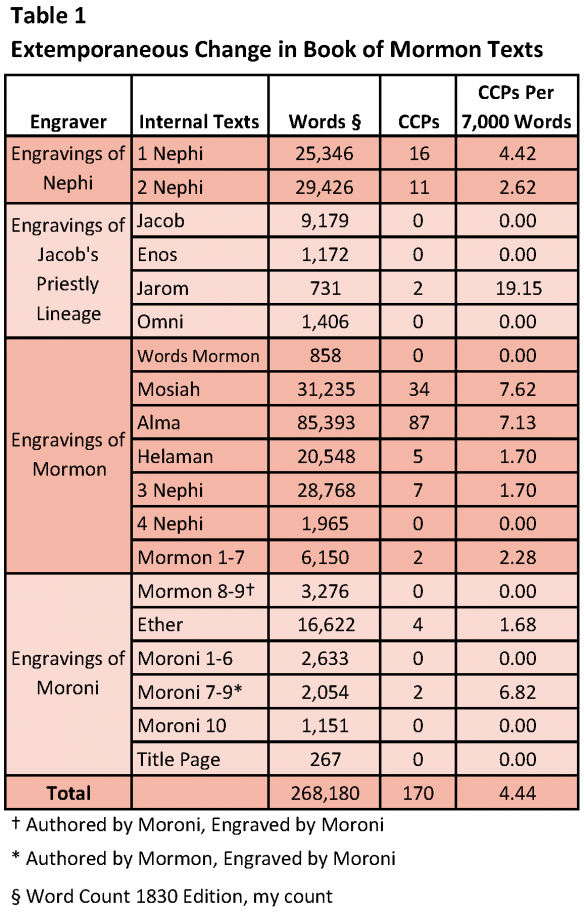

First we view the overall presentation of extemporaneous changes as they appear to a modern reader. Table 1 shows the incidence of CCPs organized by engraver and associated Book of Mormon internal texts, as well as the incidence of CCPs normalizing for the sizes of the internal texts in which they appear (Table 1, right column). For example, because there are more words in larger books like Mosiah and Alma, on average, we should expect to see more CCPs in those books and fewer in smaller books like Fourth Nephi, Jacob, or Enos. To facilitate comparison across [Page 8]various internal texts I use as a metric the number of CCPs per 7,000 words. This is called “normalizing” and we will compare average (or mean) normalized CCPs for different texts throughout this paper. For example, I find in the books of Mosiah and Alma 7.62 and 7.13 CCPs, respectively, for every 7,000 words; in Helaman there are 1.70; in First Nephi there are 4.42.14

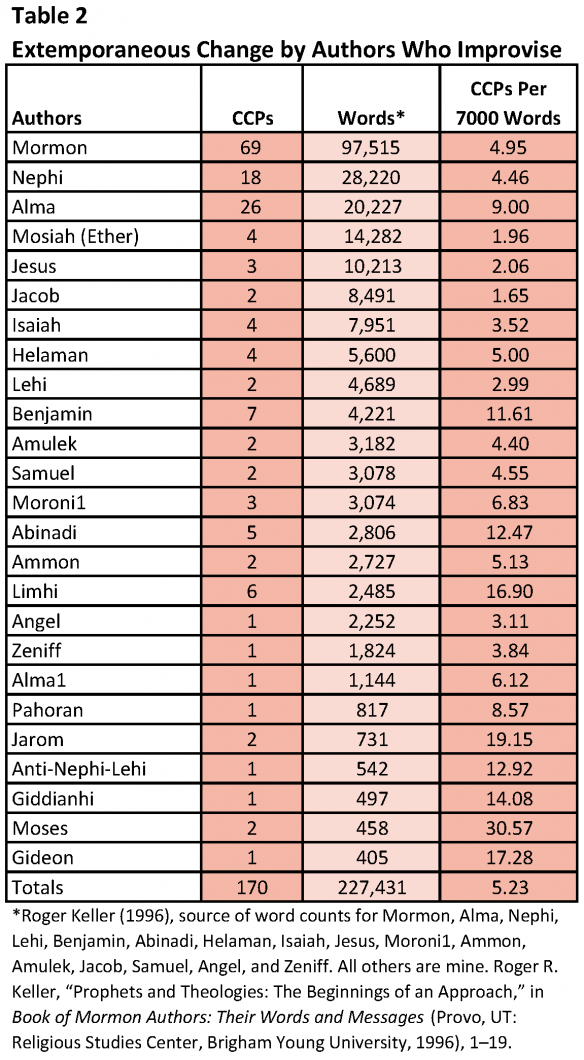

[Page 9]Table 2 shows the incidence of CCPs by author text, together with their normalized CCPs per 7,000 words. Several author texts immediately stand out as prolific with regard to extemporaneous change: Limhi 16.90 CCPs per 7,000 words, Gideon 17.28, Giddianhi 14.08, and Jarom 19.15. Alma (20,227 words of total text) is quoted at length by editor Mormon; the improvisations of his texts appear with nearly twice the intensity as those of Mormon’s texts when Mormon writes as an author (9.00 CCPs per 7,000 words for Alma versus 4.95 for Mormon).

Now let us turn to our deeper exploration of extemporaneous change at the five levels of contributors to the Book of Mormon manuscript, shown in Figure 1.

Extemporaneous Changes in Quoted Ancient Texts

We begin at the deepest level (Level 1, Figure 1) with what I identify as quoted ancient texts and some of the earliest chronologically appearing extemporaneous changes of the Book of Mormon. Most of the improvisations we will study appear in the writings of Nephite and Lamanite authors and embedded authors (Level 2) and editor-engravers (Level 3), which we begin studying in the next section. But the earliest improvisations found in the quoted ancient texts appear at a level deeper as texts that get quoted by these Level 2 and Level 3 authors and editor-engravers.

The Level 1 improvisations come from writings apparently preserved in the brass plates of Laban or the gold plates of the Jaredite people recorded in the book of Ether. Note the types of texts that get quoted in these quoted ancient texts: excerpts of Moses (Mosiah 12–13), biblical patriarch Jacob (Alma 46:24–25), high priest Melchizedek (Alma 13), and Joseph “who was carried captive into Egypt” (2 Nephi 3:4), in narratives dating approximately to the second millennium BC. Isaiah texts (eighth century bc) were also frequently quoted by Book of Mormon authors and editor-engravers, as they were also in later biblical texts such as Ezekiel, Habakkuk, Nahum, and Proverbs.15 Among the Qumran community’s Dead Sea Scrolls, the books of Deuteronomy and Isaiah are the most and third-most represented of biblical books, respectively, evidence of the importance of Moses and Isaiah to that ancient community.16 The brass plates also quote or reference the texts of four non-biblical prophets: Zenock, Neum, Zenos, and Ezias,17 who likely “date between 900 bc and the end of the Northern Kingdom in 721 bc,” according to John Sorenson,18 though we find no improvisations in these texts.[Page 10]

Types of Corrective Conjunction Phrases in Ancient Scripture

[Page 11]In studying extemporaneous change I discovered three different types of corrective conjunction phrases, each with differing traits or characteristics designed to achieve different purposes:

- Type 1: Correcting an apparent error or mistake in the text. This usually rewrites a specific idea or replaces the original expression that is judged extemporaneously to be incorrect.

- Type 2: Amplifying, clarifying, or augmenting the meaning of an original expression. This adds to the original expression with further amplifying details to clarify an apparently ambiguous, indefinite, or difficult to articulate expression.

- Type 3: Explanatory, providing a helpful literal translation of an unknown or unfamiliar original text. This addresses unfamiliar words or phrases marked by the author’s deliberate attempt to provide a literal definition, usually marked by the words “which by interpretation is;” the New Testament sometimes uses the words “that is to say.”19

In the Book of Mormon we see these three types of CCPs in the quoted ancient texts of seminal prophets, as well as in the writings of other authors. For example, the following improvisation illustrates a Type 2 Amplifying extemporaneous change that amplifies, clarifies, and augments the meaning, found in a quoted ancient text of Isaiah appearing as a quotation in an oration by the Book of Mormon’s Jacob:

Yea, for thus saith the Lord:

Have I put thee away or have I cast thee off forever?

For thus saith the Lord:

Where is the bill of your mother’s divorcement?

To whom have I put thee away?

Or to which of my creditors have I sold you?

Behold, for your iniquities have ye sold yourselves,

and for your transgressions is your mother put away.

Earliest Text, 94; 2 Nephi 7:1; see also Isaiah 50:1

This passage is a call to Nephite listeners to remember their Israelite heritage taken from an oration by Nephite chief priest Jacob following the establishment of a new Nephite nation and new temple patterned after the Temple of Solomon (2 Nephi 5). The call itself is actually structured as a layered corrective conjunction phrase articulated by [Page 12]Jacob (line 2) that builds on the original Isaiah corrective conjunction phrase (lines 6–8), as a preface — both CCPs are marked in bold by “or.” The improvisational preface is thus an emphatic repetition of Isaiah’s original improvisational call as recorded in Jacob’s oration, or perhaps added for emphasis by a later editor-engraver (Nephi, Moroni), or still later translator (Joseph Smith).

Another example from an embedded author text of Jesus during an appearance at Bountiful shows a corrective conjunction phrase that is designed to correct an apparent error or mistake (Type 1 Correcting):20

Therefore if ye shall come unto me or shall desire to come unto me

Earliest Text, 599; 3 Nephi 12:23

The Book of Mormon also contains the third type of corrective conjunction phrase, Type 3 Explanatory, with a helpful literal translation of an unknown or unfamiliar original text, as seen in this quoted ancient text of Jared from the book of Ether:

And they did also carry with them deseret,

which by interpretation is a honey bee.

And thus they did carry with them swarms of bees

Earliest Text, 675; Ether 2:3

The improvisations we see among the quoted ancient texts of Nephite authors and engravers often provide some of the earliest examples of extemporaneous change in the Book of Mormon. But why were these particular ancient texts selected for quotation by later authors and editors? One reason, of course, is that these texts come from some of the most broadly revered figures of ancient religion — for example, Isaiah or Moses. Moses is mentioned 704 times in the Old Testament, 79 times in the New Testament, and 75 times in the Book of Mormon. Jewish scholar Benjamin Sommer said, “One might view all previous revelations as leading to the event [of Moses] at Sinai and all subsequent ones as echoing it, repeating it, building upon it, or pointing toward its importance; certainly that is the way Jewish tradition has come to regard the Sinai revelation.”21 Similarly, Isaiah is quoted in twelve books of the New Testament (66 times)22 and in four books of the Old Testament;23 he is quoted by Jesus in the New Testament eight times.24 “Thirty-two percent of the book of Isaiah is quoted in the Book of Mormon; another three percent is paraphrased.”25

A second possible reason for the selection of these improvisational quoted ancient texts is that extemporaneous changes are often striking [Page 13]and noteworthy, catching the reader’s (and the author’s or editor-engraver’s) attention. This can be seen in a Moses improvisational ancient text, quoted in a narrative of Nephite martyred prophet Abinadi, which contains “the commandments [the Ten Commandments] which the Lord delivered unto Moses in the mount of Sinai” (Mosiah 12:33). In the narrative, Abinadi condemns his accusers using their own self-proclaimed religious belief system based on the Law of Moses. But note how the quotation of the commandments of Sinai pivots at the point of improvisation in the passage. The quotation begins but gets only as far as the improvisation “or any likeness of any thing.”

Thou shalt have no other God before me.

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,

or any likeness of any thing in the heaven above,

or things which is in the earth beneath.

Now Abinadi saith unto them:

Have ye done all this?

I say unto you:

Nay, ye have not.

Earliest Text, 228; Mosiah 12:35–37

The quotation of the commandments is paused midway extemporaneously at the moment of improvisation as Abinadi castigates the priests of King Noah to the point that “his face shone with exceeding luster even as Moses’ did while in the mount of Sinai while speaking with the Lord” (Mosiah 13:5) — the deliberate parallels to the Moses vision are striking. Then, after an extended confrontation with Abinadi’s accusers, notice where the quotation of the ancient text begins again — repeating in full the improvisation in the passage.

And now ye remember that I said unto you:

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,

or any likeness of things which is in heaven above,

or which is in the earth beneath,

or which is in the water under the earth.

And again, thou shalt not bow down thyself unto them nor serve them,

for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God.

[The quotation of the Ten Commandments then continues.]

Earliest Text, 229; Mosiah 13:1226

The pivot point in this account, the corrective conjunction phrase itself centered on “graven image, or any likeness,” seems to be a facilitator, [Page 14]like a mnemonic that helps organize the way the Sinai account is restated — presented here as if the improvisation had been at the forefront of the martyr’s memory, or the memory of those documenting the account. Abinadi’s discourse departs from it extemporaneously to wrestle with his accusers and then returns again later to the same point of improvisation to ensure it completes the full presentation of the commandments. The emphatic repetition of the improvisation is memorable and is a Type 2 Amplifying and clarifying improvisation to ensure a definitive and thorough understanding of “graven image.” Thus, rather than a rote recitation of the biblical Ten Commandments, instead the passage appears in context as a martyr’s improvisational restatement of the seminal Sinai revelation to Moses, essential to all Nephite believers, that was noticed, selected, and retained by editor-engraver Mormon as foundational to the identity of the Book of Mormon itself as a Mosaic text.

In summary, at its deepest level the Book of Mormon incorporates quoted ancient texts from seminal figures of ancient religion that evidently were very important to the Nephite and Lamanite communities in often compelling narratives. Improvisation is an essential element found within the ancient texts themselves but also an essential tool in the retelling of these texts by the orators, authors, or editors who quote them. Sometimes it is used to make a minor local clarification as we saw in the Ether text above, but other times it is used to add emphasis and call attention, as in Jacob’s layered improvisation that places added emphasis on Isaiah’s call to Israelite identity at the beginnings of the new Nephite nation, or the emphatic restatement of the Mosaic commandments by Abinadi using improvisation as a mnemonic pivot point to organize the retelling of the narrative.

Authors’ Use of Extemporaneous Change

Next we move up a level to study the improvisations of the authors in the Book of Mormon, usually found in a variety of embedded documents and discourses (see Level 2, Figure 1) from Nephite and Lamanite prophets, teachers, priests, kings, military leaders, and judges; Hardy provides a list of 36 embedded documents.27 The embedded documents from many of these authors include letters, epistles, speeches, decrees, memoirs, discourses, instructions, revelations, and recorded words. Embedded documents “provide an ‘original’ context,” said Paola Ceccarelli, who studied letter writing of the ancient Greeks.28 “[E]mbedded letters often carry a meaning that goes beyond the literal import of the letter [Page 15]itself and are used to give strength to the argument.”29 This kind of historical perspective should inform our understanding of how and why extemporaneous change was used by Book of Mormon authors.

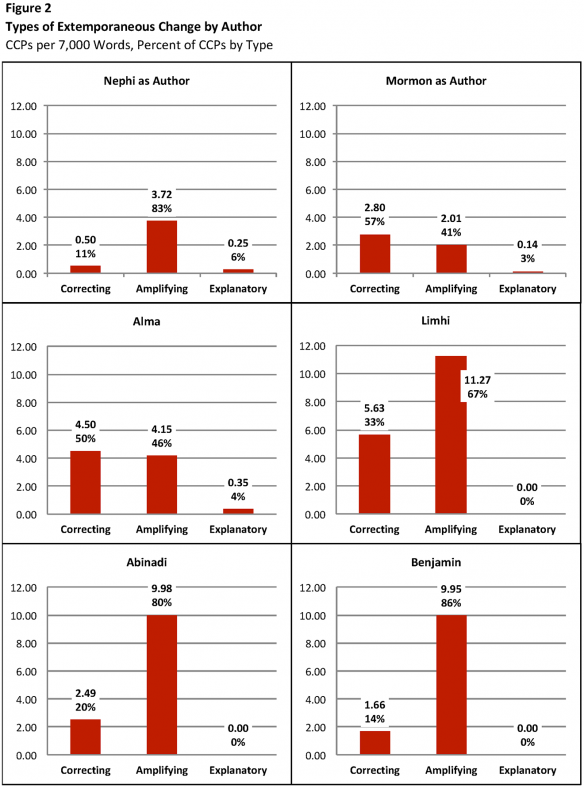

Types of Extemporaneous Change by Authors

Of the 25 authors whose texts contain improvisations, or CCPs (see Table 2), I select six that number five or greater, including Mormon’s texts written as an author (69 CCPs), Nephi’s texts written as an author (18 CCPs), and the embedded texts of authors Alma (26 CCPs), Benjamin (7 CCPs), Limhi (6 CCPs), and Abinadi (5 CCPs). First let us view types of extemporaneous change by author — Type 1 Correcting, Type 2 Amplifying, and Type 3 Explanatory. Figure 2 shows the empirical patterns of extemporaneous change for the six authors cited in Table 2 with five or more CCPs.

The improvisations found in Nephi’s author texts are 4.46 CCPs per 7,000 words (Table 2). But note how these improvisations are distributed among the three types of extemporaneous change (Figure 2). The improvisations of Nephi’s texts almost always use Type 2 Amplifying phrases (3.72 CCPs per 7,000 words), 83 percent of the time; seldom use Type 1 Correcting of mistakes or errors (0.50 CCPs per 7,000 words), 11 percent; and even less frequently use Type 3 Explanatory improvisations (0.25 CCPs per 7,000 words), 6 percent.

The improvisations found in Mormon’s author texts are 4.95 CCPs per 7,000 words, slightly more than Nephi’s. But note how differently these improvisations are distributed by type. Mormon’s texts more frequently use Type 1 Correcting phrases (2.80 CCPs per 7,000 words), 57 percent of the time; Type 2 Amplifying phrases (2.01 CCPs per 7,000 words), 41 percent; and quite infrequently Type 3 Explanatory phrases (0.14 CCPs per 7,000 words), 3 percent.

The improvisations found in Limhi’s embedded author texts are 16.90 CCPs per 7,000 words, but these improvisations primarily use Type 2 Amplifying phrases (11.27 CCPs per 7,000 words), 67 percent of the time, and secondarily Type 1 Correcting phrases (5.63 CCPs per 7,000 words), 33 percent, and never use Type 3 Explanatory phrases.

The improvisations found in Alma’s embedded author texts are 9.00 CCPs per 7,000 words, almost equally distributed between Type 1 Correcting phrases (4.50 CCPs per 7,000 words), 50 percent of the time, and Type 2 Amplifying phrases (4.15 CCPs per 7,000 words), 46 percent. Used less frequently are Type 3 Explanatory phrase (0.35 CCPs per 7,000 words), 4 percent.[Page 16]

The improvisations found in Abinadi’s embedded author texts are 12.47 CCPs per 7,000 words, mostly using Type 2 Amplifying phrases (9.98 CCPs per 7,000 words), 80 percent of the time, and less frequently Type 1 Correcting phrases (2.49 CCPs per 7,000 words), 20 percent, and never use Type 3 Explanatory phrase.

Finally, the improvisations found in Benjamin’s embedded author texts are 11.61 CCPs per 7,000 words, almost exclusively using Type 2 [Page 17]Amplifying phrases (9.95 CCPs per 7,000 words), 86 percent of the time, compared to Type 1 Correcting phrases (1.66 CCPs per 7,000 words), 14 percent, and never using Type 3 Explanatory phrase.

Statistically, the patterns of extemporaneous change (CCPs, normalized) for Authors and Type of improvisation, shown in Figure 2, are significantly different from each other (see footnote for test statistics),30 confirming that the variations in patterns observed for the three types of improvisation shown in the figures are statistically dependent on variation among the Authors studied.

The Authors’ Narrative Context – Improvisation Pattern Signatures

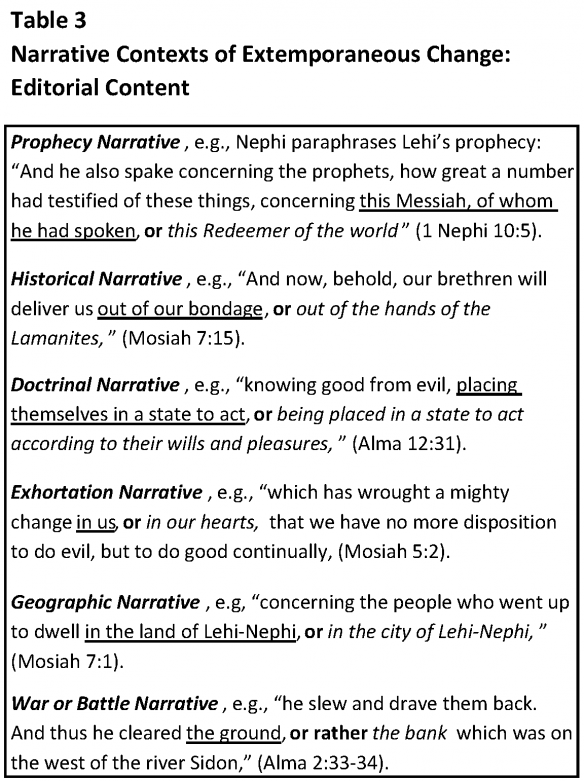

Let us extend our exploration further by studying the editorial content within which corrective conjunctions are found. Among the 170 various extemporaneous change passages I discovered among them six types of editorial content: (1) Prophecy Narrative, (2) Historical Narrative, (3) Doctrinal Narrative, (4) Exhortation Narrative, (5) Geographic Narrative, and (6) War or Battle Narrative. Table 3 shows examples of CCPs of each of these types.

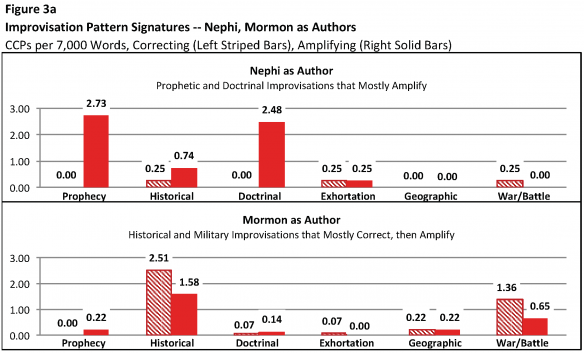

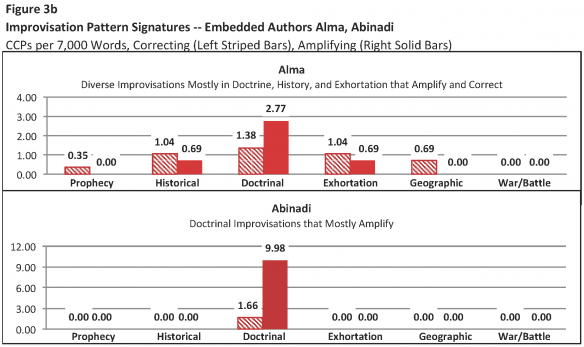

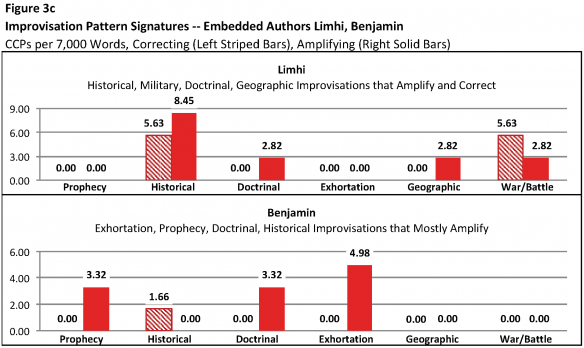

By combining the corrective conjunction phrase data with editorial content for each author, I construct profiles of extemporaneous change — I call them improvisation pattern signatures because they show the extemporaneous propensities exhibited by each author, shown in Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c. The patterns are distinct and different from each other. I hypothesize that extemporaneous change should appear in an author’s texts that (a) were perceived to be important — authorial accuracy and descriptive integrity were deemed essential — and (b) were challenging and difficult to communicate with accuracy or fidelity to the actual historical content or intended message meaning. Therefore, the patterns shown in Figures 3a through 3c are not merely representative of Nephi’s or Mormon’s editorial content, for example. Instead, they represent where extemporaneous change is found contextually in their work — that is, where they improvise. Figures 3a through 3c thus show us implicitly what appears to have been important and challenging for each author because the flow of the narrative is interrupted to improvise — to make a sudden and brief, or sometimes quite involved extemporaneous change.31[Page 18]

I test for statistically significant differences in extemporaneous change for editorial content, author, and type of improvisation using analysis of variance (called ANOVA, a common statistical method). I will explain the results in non-statistical narrative terms here, reporting the detailed statistical test results in the footnotes. Overall, the ANOVA test results generally confirm that the differences in the visual patterns we see comparing the chart panels of Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c are statistically significant.32[Page 19]

[Page 20]

[Page 21]

[Page 22]For our purposes, we are especially interested in the “interaction effects” that show relationships between variables to confirm statistically how the CCPs (average, or mean CCPs normalized) that we see with one variable depend on, or are influenced by, another variable. Thus, for example, the interaction effect of variables Author by Editorial Content is significant, confirming that the CCP pattern we see in editorial content depends on the author — that is, the different patterns of CCPs across the six editorial content categories are influenced statistically by the different authors of our study. The interaction effect of variables Type of Improvisation by Editorial Content is also significant, suggesting that the different patterns of CCPs across the six editorial content categories also depend on variation in type of improvisation.

Otherwise, the statistical tests also confirm that CCPs (again mean normalized) across the three Types of Improvisation are significantly different from each other — this is a significant main effect. And CCPs across the six Editorial Content categories are significantly different from each other, again a significant main effect. The CCPs across different Authors are not statistically different in this analysis.

Let me summarize, with some brief contextual background, the improvisation pattern signatures we see in Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c.

Mormon: Historical and Military Improvisations that Mostly Correct, Then Amplify. Mormon’s improvisations as an author appear to be driven by an impulse in history and war — evidence of an occupational orientation as a military historian. In these two categories we find the greatest incidence of Mormon’s extemporaneous changes — those places deemed important and challenging because there we see pauses to make corrections. According to the text, Mormon received a military commission at age 16 as commander “of an army of the Nephites” (Mormon 2:2), like Alexander the Great who was 16 when he led his first small Macedonian army against the Thracian Maedi tribes.33 Mormon’s improvisations are focused on Type 1 Correcting, and to a lesser degree on Type 2 Amplifying, consistent with the work of a historian first, and less so a prophet, with an apparent focus on detail.

Nephi: Prophetic and Doctrinal Improvisations that Mostly Amplify. The improvisations found in Nephi’s texts appear most frequently in prophecy and doctrinal narratives, and much less so in historical narratives. These improvisations are almost always Type 2 Amplifying and rarely Type 1 Correcting mistakes or errors. These improvisations reveal a scribal impulse in amplifying, expanding, and augmenting, [Page 23]often based on the sacred writings of others, consistent with the Small Plates of Nephi commission as a sacred record.

Alma: Diverse Improvisations Mostly in Doctrine, History, and Exhortation that Amplify and Correct. The improvisations found in Alma’s texts appear notably in doctrinal narratives, but also quite broadly in history, exhortation, geography, and prophecy narratives. His improvisations are Type 2 Amplifying and clarifying, but also just as frequently Type 1 Correcting and fixing. These improvisations appear in texts that apparently were important and challenging to Alma, showing evidence of both a sacred and a civic leadership impulse as high priest as well as chief judge of the Nephite nation, described in the Alma embedded text narratives.

Abinadi: Doctrinal Improvisations that Mostly Amplify. The prolific improvisations found in Abinadi’s texts appear solely in doctrinal texts, and mostly are Type 2 Amplifying and clarifying. They appear as remnants of the doctrinal impulses of the beginnings of formal religion among the Nephite people in Alma’s Church of God, or Church of Christ, that continued in some form for some 600 years — including the seminal Mosaic doctrines stemming from the revelations of Sinai that get amplified with respect to doctrines of atonement, Messiah, Christ as God, resurrection, and the salvation of man.

Limhi: Historical, Military, Doctrinal, and Geographic Improvisations that Amplify and Correct. The prolific improvisations found in Limhi’s texts (third-most in the Book of Mormon) appear mostly in history, then military, geography, and doctrine texts, with extemporaneous changes that are both Type 2 Amplifying or clarifying, and Type 1 Correcting or fixing. These improvisations from a king of a reclaimed lost Nephite sect preserve the historic context of the seminal beginnings of Alma’s Church of God, or Church of Christ, noted above.

Benjamin: Exhortation, Prophecy, Doctrinal and Historical Improvisations that Mostly Amplify. The prolific improvisations found in Benjamin’s texts appear in exhortation, prophecy, doctrine, and history, and are virtually always Type 2 Amplifying and clarifying. These extemporaneous changes preserve the improvisational vestiges of a royal covenant community from a notable coronation ceremony recorded in detail in Nephite sacred history.

What is noticeable from these six author improvisation pattern signatures is how distinctly different they are from each other. Some are narrowly focused in editorial content (Abinadi, Mormon, and Nephi), and others have greater content diversity (Alma, Limhi, and Benjamin), [Page 24]and emphasizing different types of improvisation — Type 1 Correcting and fixing versus Type 2 Amplifying, clarifying, and augmenting. What we see here is evidence, statistically, and visually, that the improvisations found in the texts of Book of Mormon authors appear to be works of multiple authors, rather than a single author like Joseph Smith or Moroni — both later contributors to the Book of Mormon’s construction.

Engravers’ Use of Extemporaneous Change

We now proceed to Level 3 of contributors to the Book of Mormon chain of authoring, editing, and construction (see Figure 1), to study extemporaneous change among the editor-engravers who decide and choose which texts to include and which authors to quote and embed into their respective edited works. The Book of Mormon is primarily the work of three editor-engravers: Mormon edited and engraved nearly two-thirds of the text, Nephi about one-fifth, and Moroni about one-tenth. Another eight author-engravers are self-identified in the text; all descend from the priestly lineage of the first Nephite chief priest Jacob, including Jacob, Enos, Jarom, Omni, Amaron, Chemish, Abinadom, and Amaleki.

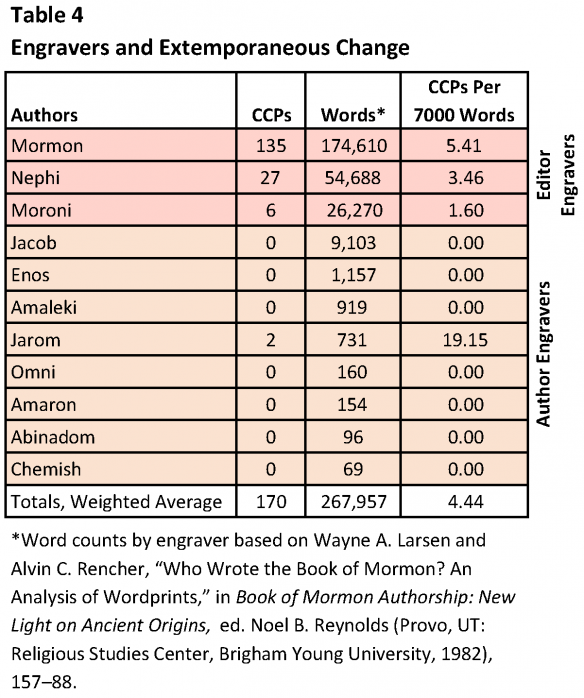

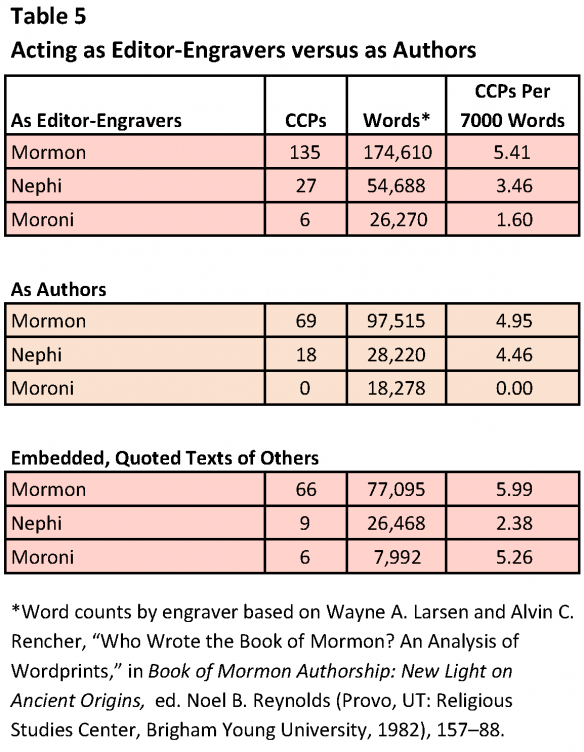

Table 4 shows total CCPs across the eleven engravers, broken out separately for editor-engravers and author-engravers. The level of improvisation found in Mormon’s edited engravings (5.41 CCPs per 7,000 words), including embedded author texts, is 56 percent higher than the improvisations found in Nephi’s engravings (3.46), and 238 percent higher than those in Moroni’s engravings (1.60 CCPs per 7,000 words). The level of improvisation in Nephi’s engravings is 116 percent higher than in Moroni’s.

Table 5 shows the overall picture of the improvisations of the editor-engravers, with a contrasting summary of the improvisations appearing in their edited works, their authored works, and the embedded texts of other authors. Here we begin to see, through extemporaneous change, the editorial designs of the editor-engravers, whether they are creators of improvisation, or managers of the improvisations of themselves and others.[Page 25]

Note that in Mormon’s editor-engraver texts there are 135 total CCPs, which include the texts of embedded authors, but in his author texts there are 69. Nearly half of the extemporaneous change we see in Mormon’s edited engraved texts is in fact attributable to other author texts embedded in his engravings (66 CCPs, or 49 percent). Mormon appears to be managing improvisational texts — between his own, and those of others. In Nephi’s editor-engraver texts there are 27 CCPs, but in his author texts there are 18. About two-thirds of the extemporaneous change we see in Nephi the engraver’s edited texts come from his authored texts; the remainder is attributable to other authors’ texts embedded in his engravings (9 CCPs, or 33 percent). Nephi appears to be more reliant on creating his own improvisations. We explore these editorial designs in detail in Article Two.[Page 26]

Note too that Mormon’s level of improvisation is higher as an editor-engraver, 5.41 versus 4.95 CCPs per 7,000 words as an author, because of the improvisational texts he embeds in his edited work from the texts of others — 5.99 CCPs per 7,000 words. Nephi’s level of improvisation is lower as an editor-engraver, 3.46 versus 4.22 CCPs per 7,000 words as an author — the opposite of Mormon — because of the less improvisational texts he embeds (2.38 CCPs per 7,000 words). Moroni’s improvisation as an editor-engraver, 1.60 CCPs per 7,000 words, is completely driven by the improvisations found in the texts of others that he embeds in his own work. These include two epistles from Mormon addressed to Moroni (containing two extemporaneous changes, in Moroni 8:22, and [Page 27]8:27) and the translated portions of the record of Ether (containing four extemporaneous changes). “The book of Ether was discovered by the Nephites about 92 bc and translated by the prophet Mosiah with the aid of the Urim and Thummim (see Mosiah 28:11–19),” said H. Donl Peterson. “The 24 plates containing Ether’s abridgment appear to have been passed down, along with Mosiah’s translation of them, from prophet to prophet until they came into Mormon’s hands. … Moroni completed the abridgment of the book of Ether on the plates of Mormon, which we often call the gold plates.”34

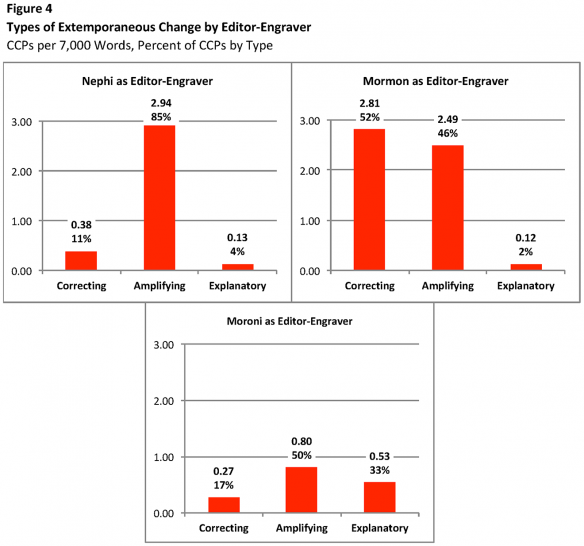

Types of Extemporaneous Change by Engravers

Again, we extend our study by examining extemporaneous change for editor-engravers — Mormon, Nephi, and Moroni —across the three types of CCPs: Type 1 Correcting, Type 2 Amplifying, and Type 3 Explanatory. Figure 4 shows the empirical patterns by type of extemporaneous change for each editor-engraver.

[Page 28]Let us contrast the improvisational patterns we see in the works of the editor-engravers (Figure 4) with those we saw in their works as authors (Figure 2). The improvisational patterns of Mormon’s edited texts (Figure 4) are similar to those we saw in Mormon’s authored texts (see Figure 2), except that Mormon’s edited texts contain a higher share of Type 2 Amplifying, clarifying, and augmenting improvisations (46 percent as editor-engraver, versus 41percent as author), and a lower share of Type 1 Correcting and fixing errors (52 percent as editor-engraver, versus 57 percent as author). Type 3 Explanatory improvisations are about the same, 2 percent as editor-engraver versus 3 percent as author. In other words, Mormon appears to embed more Type 2 Amplifying, clarifying, and augmenting improvisations into his edited works from other authors, and he creates more Type 1 Correcting and fixing improvisations in his authored texts.

By contrast, the improvisational patterns of Nephi’s edited texts (Figure 4) are nearly the same as those we saw in Nephi’s authored texts (see Figure 2), mostly using Type 2 Amplifying improvisations (2.94 CCPs per 7,000 words), 85 percent of the time; and then Type 1 Correcting phrases (0.38 CCPs per 7,000 words), 11 percent; and quite infrequently Type 3 Explanatory phrase (0.13 CCPs per 7,000 words), 4 percent.

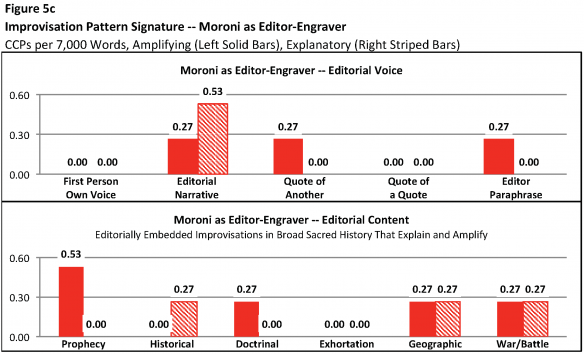

However, the improvisations found in Moroni’s edited engravings exhibit a different pattern than the other two editor-engravers, with a mix of Type 2 Amplifying improvisations (0.80 CCPs per 7,000 words), 50 percent of the time, and Type 3 Explanatory phrase (0.53 CCPs per 7,000 words), 33 percent, and then less frequently Type 1 Correcting phrases (0.27 CCPs per 7,000 words), 17 percent (see Figure 4). Here in Moroni’s engravings we see the highest levels of Type 3 Explanatory improvisations (0.53 CCPs per 7,000 words, 33 percent of the time) of all editor-engravers and authors. This is consistent with the nature of the Jaredite book of Ether, a discovered and translated record of a lost civilization with terms and proper nouns requiring definition and explanation.

The Engravers’ Narrative Context – Improvisation

Pattern Signatures

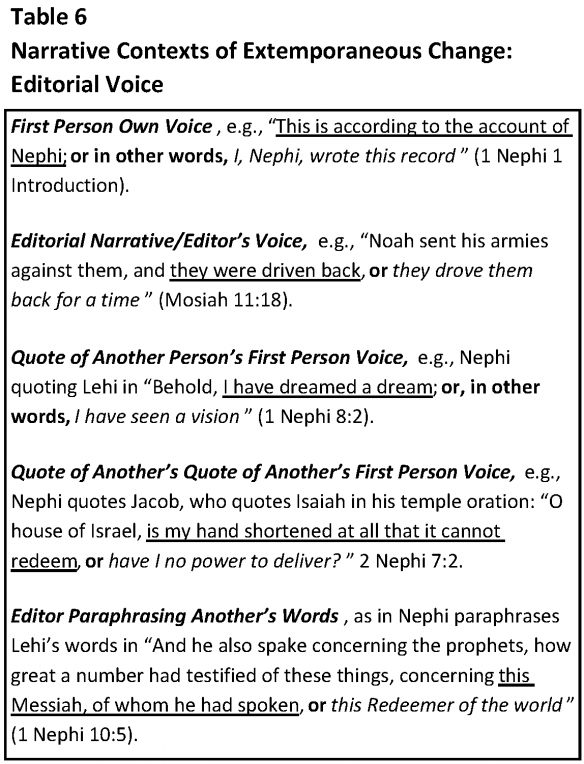

Once again, we examine extemporaneous change by comparing across editorial content categories, similar to the last section on authors. However, because editors work with the texts of other authors using varying voices, we now also cross-tabulate across different types of Editorial Voice. [Page 29]I identified the following five types of editorial voice in which corrective conjunctions occur (see Table 6 for examples of CCPs of each):

- First Person Own Voice.

- Editorial Narrative/Editor’s Voice.

- Quote of Another Person’s First Person Voice.

- Quote of Another’s Quote of Another’s First Person Voice, such as Nephi quoting Jacob, who quotes Isaiah in 2 Nephi 7:2.

- Editor Paraphrasing Another’s Words, as in Nephi paraphrasing Lehi’s words.

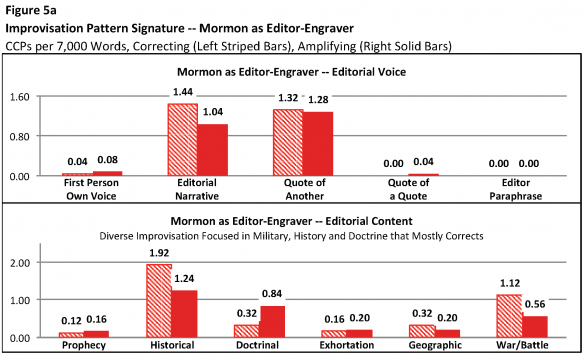

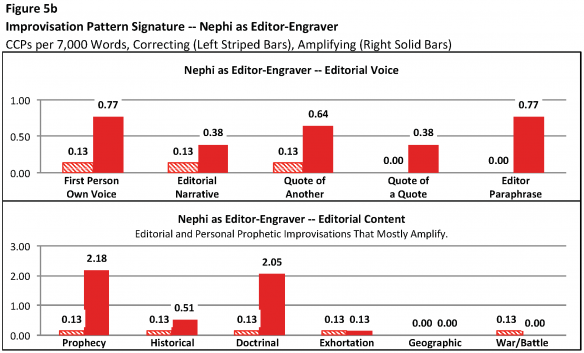

As with authors in the last section, I again construct improvisation pattern signatures that describe the improvisational propensities of each engraver, including now both editorial voice and editorial content (Figures 5a through 5c). I test for statistically significant differences in extemporaneous change, this time using two different ANOVA models: the first focuses on the variable Editorial Voice, together with Editor-Engraver and Type of Improvisation; the second focuses on Editorial Content, together with Editor-Engraver and Type of Improvisation. Once again, we are especially interested in the interaction effects that show relationships between these variables.

For Editorial Voice, the ANOVA test confirms that the pattern differences we see across the chart panels (top) of Figures 5a, 5b, and 5c are statistically significant.35 The interaction effect is significant for Editor-Engraver by Editorial Voice, confirming that the CCP pattern we see in editorial voice depends on the editor-engraver — that is, the CCP patterns across the five editorial voice categories are influenced statistically by variation in the editor-engravers of our study. The interaction effect of Editor-Engraver by Type of Improvisation is also significant, confirming that the CCP patterns we see in type of improvisation also depend on editor-engraver and are influenced statistically by variation in the editor-engravers. Otherwise, the statistical tests also confirm that CCPs (again mean normalized) are significantly different across the five Editorial Voice categories, and are significantly different across the three Types of Improvisation, both significant main effects. The CCPs for the three different Editor-Engravers are different from each other, with a marginally significant main effect.[Page 30]

For Editorial Content, the ANOVA test confirms that some of the pattern differences we see across the chart panels (bottom) of Figures 5a, 5b, and 5c are statistically significant.36 One interaction effect is significant, Editor-Engraver by Type of Improvisation, confirming that type of improvisation depends on editor-engraver — that is, the CCP patterns across the three types of improvisation are influenced statistically by variation in the editor-engravers of our study.[Page 31]

[Page 32]

[Page 33]

[Page 34]The other interaction effects are not significant in this editorial content model. Otherwise, the statistical tests also confirm that CCPs (again mean normalized) are significantly different across the three Types of Improvisation, a significant main effect, are marginally significant across the three Editor-Engravers, also a main effect, and are not significant across the six categories of Editorial Content.

Taken together, these statistical results point to interesting significant findings. The important interaction effects suggest the different editor-engravers have a significant influence on the types of improvisation we see in the Book of Mormon, and also on the editorial voice in which their improvisations appear. Although we did not find a significant Editor-Engraver by Editorial Content interaction in these editor-engraver models, we did find a significant Author by Editorial Content interaction in the author model of the last section, which confirms that the different authors have a significant influence on the improvisation patterns associated with their editorial content. Generally, differences across the three Types of Improvisation, and across the five categories of Editorial Voice, are consistently significant; both are main effects. Yet, although differences across the six categories of Editorial Content were not significant in the editor-engraver models, the differences were significant in the author model of the last section, again a main effect in the author model that complements the findings of the editor-engraver models.

So statistically, the overall results point to Levels 2 and 3 in the chain of authoring, editing and construction of the Book of Mormon (Figure 1) as the key to understanding extemporaneous change. The improvisational patterns we see are broadly driven by its editor-engravers (with respect to type of improvisation and editorial voice), but also in a complimentary way by its authors (regarding editorial content). The results confirm that extemporaneous change is the product of not one, but multiple actors using an array of improvisational means (types, editorial voice, editorial content) that appear to be statistically complimentary — editor-engravers improvising while using the improvisational works of authors to complement their own editorial designs. We see this in the improvisation pattern signatures of Figures 5a, 5b, and 5c, which, similar to the Author section, I summarize briefly.

Mormon: Diverse Improvisation Focused in Military, History, and Doctrine that Mostly Corrects: As an editor-engraver, Mormon’s improvisations now appear in broader, more diverse editorial content than we saw with Mormon as author, as he imports the [Page 35]improvisational texts of other authors whose improvisations appear in doctrine, exhortation, and prophecy texts. His personally-authored improvisations are driven by his impulse as a military historian, but his imported editorial improvisations are driven by his impulse as a prophet with a commission to compile and engrave “all the sacred engravings concerning this people” (Mormon 1:3).

Nephi: Editorial and Personal Prophetic Improvisations that Mostly Amplify. Nephi’s improvisation patterns appear to be nearly the same whether acting as editor-engraver or author —centered in prophecy and doctrinal narratives, and occasionally in historical narratives, with diverse editorial voices, but especially his own first person voice or paraphrasing another’s words (often his father Lehi’s), and with Type 2 Amplifying improvisations. Though Nephi’s career is spent as first king and nation builder of the Nephite people, navigating the separation from the Lamanite tribes, his impulse is to improvise more as a prophet than as a king.

Moroni: Editorially Embedded Improvisations in Broad Sacred History that Explain and Amplify. Moroni’s improvisations are editorially imported mostly from the Jaredite record and appear broadly across prophecy, history, doctrine, geography, and war/battle narratives. He retains an unusual mix of Type 2 Amplifying and Type 3 Explanatory, but little Type 1 Correcting improvisations, reflecting the sacred and historical character of the hitherto unknown book of Ether, translated centuries earlier by Mosiah. His career involves immersion in sacred texts and religious service — he preserves the ordination, sacramental, and administration protocols of Christ’s first century church in the new world (Moroni 1–6) — and we get a glimpse of how he works by viewing the improvisational texts he chooses to import.

Discussion

We have explored and then tested the patterns observed in the first three layers of successive strata of the Book of Mormon’s compilation and construction studying extemporaneous change and improvisation, beginning with the quoted ancient texts where we find improvisations of seminal prophets of ancient religion, such as Moses and Isaiah (Level 1, Figure 1); then the improvisations in the authors’ texts from Nephite and Lamanite prophets, judges, kings, military leaders, and teachers (Level 2); and finally the improvisations found in the larger editor-engraver works of Mormon, Nephi, and Moroni (Level 3), all spanning a thousand years of narrative history. In so doing we begin to see up [Page 36]close the workings of ancient writers, editors, engravers, and translators of the Book of Mormon. Through extemporaneous changes that appear in their writings and orations we see evidence of their personas, their editorial decisions, their improvisations, and the creative impulses that enable them to construct a many-faceted, complex, and rich narrative sacred history. These awkward extemporaneous changes at different levels and strata underscore that this is an imperfect work, apparently from its earliest and deepest contributors, constructed over layers of time and setting.

The evidence we have seen of statistically significant improvisational patterns across authors and editor-engravers is compelling. These improvisational patterns appear evident at deeper levels of the Book of Mormon’s construction (Levels 2 and 3, Figure 1), as if they had been preserved through temporal layers of later copying, editing, engraving, and translating — and therefore likely originating with the early authors and editor-engravers of these levels. Yet we cannot be certain of this, and still must address, in Article Two, the roles of Moroni and Joseph Smith as late contributors to the Book of Mormon’s compilation and translation in either preserving or inscribing their own improvisations onto the narrative texts that lay before them. In any event, the statistical work shown here points to multiple authors and editor-engravers whose improvisational impulses speak from the text of the Book of Mormon.

Our findings dovetail with existing research on the authors and engravers of the Book of Mormon. According to Brant Gardner, Nephi shows evidence of having been trained as a formal scribe in ancient Jerusalem, and some of his scribal training is consistent with the extemporaneous change patterns uncovered in my research. “Nephi not only includes passages from Isaiah but also uses Isaiah as a foundation and springboard for his own revelation. As with the pesharim [interpretive commentary on Hebrew scripture], the scripture served as the springboard for a text that applied that scripture to a current situation. … What Nephi begins in chapter 25 is not an explanation of Isaiah but rather an expansion of Isaiah.”37 Gardner’s description parallels closely Nephi’s improvisation pattern signature shown earlier — rarely prone to Type 1 Correcting, and almost always inclined to Type 2 Amplifying of mostly prophetic or doctrinal texts, usually with a first-person editorial voice or telling another’s words. Hardy said: “[I]n the postnarrative chapters we come to know Nephi as a reader — poring over ancient texts, offering alternative interpretations, interweaving his own revelations with the words of past prophets.”38

[Page 37]Regarding Mormon, Hardy said, “Mormon’s historiographical impulse, by contrast, is manifest in his meticulous attention to chronology and geography.”39 “[H]e is a historian rather than a memoirist.”40 “Unfortunately, the demands of historical accuracy, literary excellence, and moral clarity do not always fit well together, and if we read closely we can see Mormon struggling to reconcile them.”41 Richard Neitzel Holzapfel said, “[A]n examination of the editorial devices used by Mormon shows his sincere concern for credibility and editorial honesty. … [His work] is clearly the product of an excellent ancient historian concerned with naming and adhering to his sources while presenting an edited account that exhibits a spiritually motivated understanding of history and purpose.”42 These descriptions are consistent with my findings of Mormon’s improvisation pattern signature as a detailed military historian, primarily focused on Type 1 Correcting and secondarily on Type 2 Amplifying, who weaves in the improvisational texts of others to create a more sacred scriptural record.

Regarding Moroni, Hardy said: “[W]e might expect [Moroni] to take a different approach to the task of writing history than his father [Mormon], and that is exactly what we find. Moroni apparently did not feel the tension of competing agendas in the same way that Mormon did … there is much less reworking of historical sources.”43 “Moroni is not so much composing [his own] conclusion as constructing it, extracting phrases from particular texts by Nephi and Mormon in order to weave them together and thereby unify the voices of these two illustrious predecessors.”44 This is what we see too with Moroni’s improvisational work, never authoring his own improvisation (compared to his father’s many improvisations), but selecting and importing those key improvisational texts that help explain the complexities of the unknown Jaredite people.

With these initial explorations behind us, in the next paper we turn to the design and construction of extemporaneous change as found in the Book of Mormon to address this important question: Despite the evidence for multiple author and editor improvisation, is there evidence still that the improvisations of the Book of Mormon are ancient or modern in origin? Certainly it seems plausible that a translator such as Smith, or even Moroni, would need to lean on extemporaneous change as an instinctive tool to produce a better dictation or translation of an ancient work. Therefore, what kind of improvisation do we see by these later contributors as viewed from the perspective of the entire [Page 38]Book of Mormon corpus? There is more to discover in our investigation into extemporaneous change.

[The author notes his gratitude to the editor, three anonymous peer reviewers, and Matt Gregas, Senior Research Statistician at Boston College, for their helpful insights and comments on these papers.]

Endnotes

- Grant Hardy, “Introduction,” in Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), xix–xx.

- Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 739–40.

- Skousen, Earliest Text, 745–789. The 719 changes cited by Skousen represent only a small subset of the various changes made to the Book of Mormon during Smith’s life. For a complete presentation see Skousen’s Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part One (2004), Part Two (2005), Part Three (2006), Part Four (2007), Part Five (2008), and Part Six (2009), Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship.

- Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary defined conjunction as “a connective or connecting word; an indeclinable word which serves to unite sentences or the clauses of a sentence and words, joining two or more simple sentences into one compound one, and continuing it at the pleasure of the writer or speaker.” Conjunction, American Dictionary of the English Language, Webster’s Dictionary 1828 – Online Edition, accessed 12 May 2014, http://webstersdictionary1828.com. Of the various types of conjunction phrases that join sentence clauses together — concatenating (A and B), sequential (A and then B), alternative (either A or B) and corrective (A1, or rather A2) — I focus specifically on conjunction phrases that are corrective.

- Mary Lou Treat reports early research on clarifying and correcting phrases in the Book of Mormon. “All of these thoughts finally jelled together to the point where I could ask, ‘What happens when an engraver makes a mistake?’ It seemed logical that a clarifying phrase could correct an unclear sentence. Hence the phrase ‘or rather’ or something similar would be utilized.” Mary Lee Treat, “No Erasers,” in Recent Book of Mormon Developments, ed. Raymond C. Treat (Independence, MO: Zarahemla Research Foundation, 1984), 54.

- Speech of Hon. Abraham Lincoln (At Columbus, OH, September, 1859), accessed 14 May 2014, http://www.bartleby.com/251/8.html.

- Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 14:161, accessed 9 Sept 2016, http://jod.mrm.org/14/156.

- Brant A. Gardner, “Literacy and Orality in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture (Volume 9, 2014), 73. Accessed 9 Sept 2016, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/literacy-and-orality-in-the-book-of-mormon/.

- For corrective conjunction phrases throughout this paper, I use three forms of emphasis for presentation: the phrase to be corrected is underscored; the corrective conjunction is bolded; and the modification or fix is italicized.

- All Book of Mormon references cite The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text by Skousen (2009). Skousen used “sense lines” to break up the text into phrases and clauses (the original manuscript contained no sentence breaks or punctuation). Skousen explained that, since the Book of Mormon translation was dictated orally by Joseph Smith to scribes, “the first verbalization of the text would have sounded something like the result of reading the sense-lines out loud. … Sense-lines can assist readers in differentiating phrases and clauses, identifying constituent grammatical units, and keeping track of subjects, main verbs, and modifiers.” Skousen, Earliest Text, xlii–xliii.

- “To dispense, as to administer justice or the sacrament,” Administer, American Dictionary of the English Language, Webster’s Dictionary 1828 — Online Edition, accessed 4 September 2016, http://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/administer.

- “Leonardo da Vinci: Italian artist, engineer, and scientist,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 24 April 2016, http://www.britannica.com/biography/Leonardo-da-Vinci/The-Last-Supper.

- I refer to Moroni, son of Mormon, author of the last book in the Book of Mormon, as Moroni. I refer to an earlier Moroni, Nephite military leader recorded in the book of Alma, as Moroni1. I refer to Alma (the Younger), high priest and chief judge of the Nephite people, as Alma. His father, founder of the first Nephite Church of Christ, will be referred to as Alma1. I refer to Nephi, son of Lehi, as Nephi.

- Roger Keller uses a similar approach in which he measures thematic word occurrences per thousand words of author text. Roger R. Keller, “Prophets and Theologies: The Beginnings of an Approach,” in Book of Mormon Authors: Their Words and Messages (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 1–19. This type of normalizing count data for statistical comparison is used in various settings, such as normalizing census data counts for different towns, cities, or neighborhoods of varying size (Normalizing Census Data, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, accessed 14 July 2016, http://web.mit.edu/11.520/www/labs/lab5/normalize.html).

- Ezekiel (4:16, quoting Isaiah 3:1), Habakkuk (2:14, quoting Isaiah 11:9), Nahum (1:15, quoting Isaiah 52:7), and Proverbs (1:16, quoting Isaiah 59:7). See John A. Tvedtnes, “Was Joseph Smith Guilty of Plagiarism?” The FARMS Review 22/1 (2010), accessed 4 July 2016, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1814&context=msr.

- The Qumran caves included 21 copies of the book of Isaiah, 26 copies of Deuteronomy, and 36 copies of Psalms. See Emanuel Tov, Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible, and Qumran: Collected Essays (Tuebingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), 42.

- Zenock is referenced and quoted in 1 Nephi 19:10, Alma 33:15–17; 34:7; Helaman 8:20; 3 Nephi 10:15–16; Neum in 1 Nephi 19:10; Zenos in 1 Nephi 19:10–17, Jacob 5:1, 6:1, Alma 33:3–15, 34:7, Helaman 8:19, 15:11, 3 Nephi 10:15–16, and Ezias in Helaman 8:20. See Tim Barker, “The Lost Books of the Book of Mormon,” 17 October 2010, LDS Studies, accessed 4 July 2016, http://lds-studies.blogspot.com/2010/10/lost-books-of-book-of-mormon.html.

- John L. Sorenson, “The Brass Plates and Biblical Scholarship,” Dialogue Volume 10, Number 4 (Autumn, 1977), 34.

- Here are examples of extemporaneous change from the New Testament. Galatians 4:9: “But now, after that ye have known God, or rather are known of God, how turn ye again to the weak and beggarly elements, whereunto ye desire again to be in bondage?” First Corinthians 4:3: “But with me it is a very small thing that I should be judged of you, or of man’s judgment: yea, I judge not mine own self.” And Acts 1:19: “And it was known unto all the dwellers at Jerusalem; insomuch as that field is called in their proper tongue, Aceldama, that is to say, The field of blood.” For examples from the Old Testament and the Apocrypha see Exodus 20:4, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above.” Ruth 1:16: “And Ruth said, Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee.” Or 2 Maccabees 6:23: “But he began to consider discreetly, and as became his age, and the excellency of his ancient years, and the honour of his gray head, whereon was come, and his most honest education from a child, or rather the holy law made and given by God; therefore he answered accordingly, and willed them straightways to send him to the grave.” The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments: Translated Out of the Original Tongues and with the Former Translations Diligently Compared and Revised (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, Little, and Wilkins, Richardson and Lord, Lincoln and Edmands, Crocker and Brewster, Munroe and Francis, and R. P. and C. Williams, 1828), 124.

- I include this to provide an example of a Type 1 Correcting improvisation, from Jesus, although technically the embedded texts of Jesus in Third Nephi are Level 2 author texts, included in the larger narrative by editor-engraver Mormon.

- Benjamin D. Sommer, Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 39.

- See Ron Graham, Background to Isaiah, simplybible.com, accessed 1 August 2016, http://www.simplybible.com/f591.htm.

- Ezekiel (4:16, quoting Isaiah 3:1), Habakkuk (2:14, quoting Isaiah 11:9), Nahum (1:15, quoting Isaiah 52:7), and Proverbs (1:16, quoting Isaiah 59:7). See John A. Tvedtnes, “Was Joseph Smith Guilty of Plagiarism?” The FARMS Review 22/1 (2010), accessed 4 July 2016, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1814&context=msr.

- Jeffrey Kranz, Which Old Testament Book Did Jesus Quote Most?, Biblia blog, accessed 1 August 2016, https://blog.biblia.com/2014/04/which-old-testament-book-did-jesus-quote-most/.

- “Old Testament Prophets: Isaiah,” Ensign (September 2014), accessed 1 August 2016, https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/2014/09/old-testament-prophets-isaiah?lang=eng.

- I count in this passage one CCP, signaled by “or,” which is followed by the amplification “any likeness of things which is in heaven above, or which is in the earth beneath, or which is in the water under the earth.” The remaining repetitions of “or” relate to another use of conjunctions to concatenate ideas together in a series or chain, as in: “written by way of commandment, and also by the spirit of prophecy and of revelation.” Skousen, Earliest Text, 3 [title page].

- Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Readers Guide (NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), see chapter 5, footnote 6.

- Paola Ceccarelli, Ancient Greek Letter Writing: A Cultural History (600 BC–150 BC) (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), v.

- Ceccarelli, Ancient Greek Letter Writing, 276.

- CCPs normalized, two-way chi square, Author by Type, Fisher’s exact test using Monte Carlo estimation. The relation between these variables was significant, X2 (10, n=18) = 19.374, p=0.010. We can reject the null hypothesis of independence. Monte Carlo estimation of p values based on 95 percent confidence interval and 1,000,000 sampled tables. CCPs normalized per 15,000 words for statistical algorithm assumptions.

- To facilitate presentation clarity I show chart plots in Figures 3a through 3c that include Type 1 Correcting and Type 2 Amplifying improvisations but do not include Type 3 Explanatory improvisations because of their low frequency counts. I do include all three types of improvisation in the statistical analyses reported throughout this paper.

- The CCP count data is measured in whole number form, but after normalizing for text size is converted to real number form with decimal representations. In this form I use Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test the null hypothesis. Examination of the response variable showed a right skew, so the response variable was transformed using a log transformation. The data then appeared to be more normally distributed. The ANOVA test is significant, rejecting the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean CCPs (normalized), for main effects Editorial Content (F(5,50)=3.759, p=0.006), and Type of Improvisation (F(2,50)=17.160, p=0.000), and is not significant for Author (F(5,50)=1.577, p=0.184). The ANOVA also is significant for the two-way interactions Author by Editorial Content (F(25,50)=1.952, p=0.022), and Type of Improvisation by Editorial Content (F(10,50)=2.343, p=0.023), and is not significant for Author by Type of Improvisation (F(10,50)=1.302, p=0.255), R Squared=0.745. CCPs normalized per 15,000 words for statistical algorithm assumptions.

- Michael Thomas, “History: Top 10 Teenage Military Leaders,” accessed 31 August 2016, http://listverse.com/2013/06/29/top-10-teenage-military-leaders/.

- H. Donl Peterson, “Moroni, the Last of the Nephite Prophets,” in Fourth Nephi, From Zion to Destruction, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 235–49. John Welch offers a similar explanation from his research on the book of Ether. John W. Welch, Preliminary Comments on the Sources behind the Book of Ether (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 1996).

- Examination of the response variable showed a left skew, so the response variable was transformed using a log transformation. The data then appeared to be more normally distributed. The ANOVA test is significant, rejecting the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the mean CCPs (normalized) for main effects Editorial Voice (F(4,24)=6.472, p=0.001) and Type of Improvisation (F(2,24)=10.908, p=0.000), and marginally significant for Editor-Engraver (F(2,24)=2.603, p=0.095). The ANOVA is also significant for the two-way interactions Editor-Engraver by Type of Improvisation (F(4,24)=3.587, p=0.020) and Editor-Engraver by Editorial Voice (F(8,24)=2.363, p=0.049), R Squared=0.782. CCPs normalized per 15,000 words for statistical algorithm assumptions.

- Examination of the response variable showed a left and right skew, so the response variable was transformed using a log transformation. The data then appeared to be more normally distributed. The ANOVA test is significant, rejecting the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the mean CCPs (normalized) for main effect Type of Improvisation (F(2,20)=9.479, p=0.001), is marginally significant for Editor-Engraver (F(2,20)=3.081, p=0.068), and is not significant for Editorial Content (F(5,20)=1.916, p=0.137). The ANOVA is also significant for the two-way interaction Editor-Engraver by Type of Improvisation (F(4,20)=3.382, p=0.029) but not for Editor-Engraver by Editorial Content (F(10,20)=1.732, p=0.142) or Type of Improvisation by Editorial Content (F(10,20)=1.581, p=0.184), R Squared=0.803. CCPs normalized per 15,000 words for statistical algorithm assumptions.

- Brant A. Gardner, “Nephi as Scribe,” Mormon Studies Review 23/1 (2011), 52–53, emphasis added.

- Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 59, emphasis added.

- Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 91, emphasis added.

- Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 99, emphasis added.

- Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 102, emphasis added.

- Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Mormon, the Man and the Message,” in Fourth Nephi, From Zion to Destruction, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 117–31.

- Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 225, emphasis added.

- Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 254, emphasis added.

Go here to see the 7 thoughts on ““Improvisation and Extemporaneous Change in the Book of Mormon (Part 1: Evidence of an Imperfect, Authentic, Ancient Work of Scripture)”” or to comment on it.