Abstract: Although Joseph Smith has been credited with “approximately seven full school years” of district schooling, further research supports that his education consisted of basic instruction in “reading, writing and the ground rules of arithmetic” comprising “less than two years of formal schooling.” The actual number of terms he experienced in common schools in upstate New York is probably less critical since the curricula in district schools did not then teach creative writing, composition, or extemporaneous speaking. If Joseph Smith learned how to compose and dictate a book, extracurricular activities would likely have been the training source. Six of those can be identified: (1) private Bible studies, (2) Hyrum Smith’s possible tutoring in 1813, (3) participation in local religious activities, (4) involvement with the local juvenile debate club, (5) occasional family storytelling gatherings, and (6) brief participation as an exhorter at Methodist meetings. Three of his teachers in Kirtland in 1834–1836 recalled his impressive learning ability, but none described him as an accomplished scholar. A review of all available documentation shows that no acquaintance at that time or later called him highly educated or as capable of authoring the Book of Mormon. Despite its current popularity, the theory that Joseph Smith possessed the skills needed to create the Book of Mormon in 1829 is contradicted by dozens of eyewitness accounts and supported only by minimal historical data.

As a controversial personality of the early nineteenth century, Joseph Smith Jr. has been called a prophet, treasure seeker, translator, city organizer, prisoner, freemason, banker, lieutenant general, religious genius, polygamist, martyr, and author. This last title has generated controversy because Joseph Smith reported he was not the author of the Book of Mormon, instead declaring its words came to him by “the gift [Page 2]and power of God.”1 Critics reject this claim, asserting that naturalistic explanations can answer the question, “Where did all the words come from?” For example, Richard S. Van Wagoner refers to “secondary literature of some 6,000-plus titles” that scrutinize the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith’s “empirical claims.” Then Van Wagoner confidently asserts: “The main conclusion of this particular growing body of work is that there is no element in the Book of Mormon that cannot be explained naturalistically.”2

John L. Sorensen summarizes some overall concerns: “The question of the origin of the Book of Mormon is not a trivial one for scholars. Hundreds of both popular and scholarly publications have appeared related to this question, and they continue to be issued. However, only a few theories about how the book came into being have been taken seriously by conventional scholars.”3 Although skeptics may have mixed and matched their hypotheses at times, six primary naturalistic theories have been, and still are, promoted:4

- Solomon Spalding wrote the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon.

- Collaborators helped Joseph Smith create the text.

- Joseph Smith’s mental illness enhanced his writing ability.

- [Page 3]Joseph functioned as a medium and produced the Book of Mormon as automatic writing.

- Joseph Smith employed the oral performance skills of an accomplished orator, like a revivalist preacher.5

- Joseph Smith’s intellect was sufficient to create the Book of Mormon.

The various theories are not exclusive of each other, and some authors have advanced more than one, perhaps without necessarily realizing it. This article examines the last of these theories — that of Joseph Smith’s intellect — by investigating everything that can be known about Joseph’s education and cognitive abilities from the documentary record. Reports discussing his oratorical skills are also included since the first draft of the Book of Mormon was dictated, not written.

Before proceeding, it should be noted that all historical research has limitations. Documentation of almost all studied events is, at best, incomplete. The lack of adequate eyewitness accounts often forces scholars to rely on secondary sources (if they exist). In either case, the biases of the reporters, if they can be discerned, color their accounts. Consequently, most historical data contains ambiguities, gaps, or contradictions, allowing for more than one valid interpretation.

Acknowledging these limitations, this paper attempts to give a voice to every relevant historical reference to Joseph Smith’s education and intellect. Thus, by bringing all interested observers to the same documentary precipice, each can view the data and judge for themselves. While differing opinions will undoubtedly emerge, this transparency could create a no-spin zone for informed readers who discuss this subject in the future.

Joseph Smith’s Formal Education

Joseph Smith grew up in a family that valued education. Both his father, Joseph Smith Sr., and grandmother, Lydia Mack, had taught school. Their academic involvement demonstrated their devotion to learning, probably making education a priority in their homes.

[Page 4]Possible Tutoring by Hyrum When Age Seven

Besides Joseph Smith’s formal attendance at local schools, it is possible his older brother Hyrum supplemented his learning through personal tutoring. Lucy Mack Smith, their mother, recalled that while living in Lebanon, New Hampshire, in 1811, eleven-year-old Hyrum attended the “academy in Hanover.”6 “The academy, or Moor’s Charity School, was associated with Dartmouth College in Hanover, a few miles north of the Smith home and on the same side of the Connecticut River,” writes Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith’s biographer. “Lucy did not explain why Hyrum was chosen to attend, but it may have been simply because his cousin of about the same age, Stephen Mack, was already a student there.”7

Hyrum returned to the Smith home in 1813 sick with typhus, which all family members contracted. Joseph subsequently experienced a chronic knee infection requiring advanced surgical treatment administered by Dr. Nathan Smith of the nearby Dartmouth Medical School.8 Afterward, Hyrum “sat beside him almost incessantly day and night.”9 It is possible that Hyrum, then thirteen, tutored his seven-year-old little brother Joseph for several months at that time.10 The next year, Joseph left for Salem, Massachusetts, to convalesce at the home of his uncle Jessee Smith.11

At Least Five District School Terms

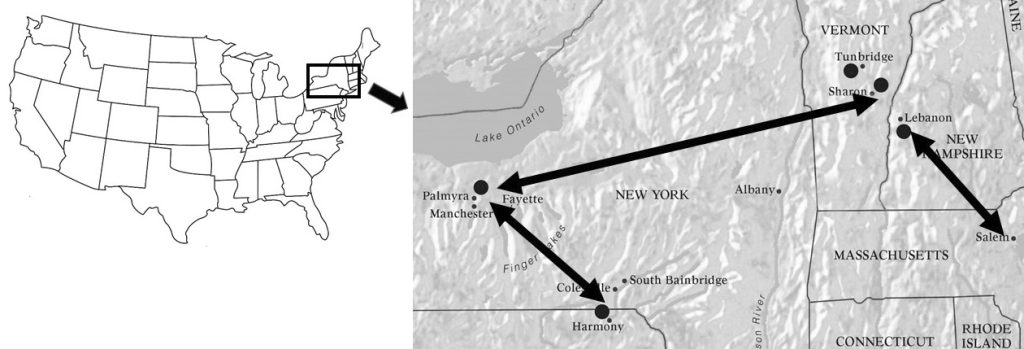

Between 1808 and 1826, Joseph Smith attended local common schools in five or six areas.12 District schools held two terms each year (summer and winter), and his attendance during at least one term can be documented in Royalton, Vermont (1809–1812); West Lebanon, New Hampshire [Page 5](1812–1815); and Palmyra (1817–1821), Manchester (1821–1825), and South Bainbridge (1825–1826), New York.13 (See Figure 1.) Researcher William L. Davis observes that Joseph may have been eligible to attend up to twenty-two terms between 1809 and 1826. Although the exact number he attended continues to be debated, Davis speculates that Joseph Smith’s “overall estimated time … in formal education” (beyond the five terms documented in the historical record) was “equivalent of approximately seven full school years,” or fourteen terms.14

Figure 1. Arrows show Joseph Smith’s pre-1829 travels and the six locations where he attended or may have attended local district schools.

Several of Joseph Smith’s contemporaries remember attending school with him, but some reported he did not always take advantage of educational opportunities. Pomeroy Tucker accused Joseph of “hunting and fishing … and idly lounging around the stores and shops in the village … instead of going to school like other boys.”15 Perry Benjamin Pierce also wrote: “The boys grew up without desire for education … ‘None of them Smith boys ever went to school when they could get out of [Page 6]it.’”16 Joseph’s younger brother William reported his personal experience, which may have approximated Joseph’s, of “limited opportunities for acquiring an education.” William added: “being like most youths, more fond of play than study, I made but little use of the opportunities I did have.”17

District Schools in the 1820s America

Regarding Joseph Smith’s training to become the author of the Book of Mormon, the precise number of terms he spent in district school classrooms may be less important because the curriculum touched only minimally the skills authors usually seek to develop. In their book, A History of Education in American Culture, R. Freeman Butts and Lawrence A. Cremin explain:

The typical one-room district school was usually attended by a variety of age groups, running all the way from children of four or five to adolescents in their teens … The early district schoolroom was most often a picture of a teacher seated at a central desk with one child after another approaching, reciting from text or memory, being rewarded with a smile or a blow depending on the effectiveness of the recitation, and returning to his seat.18

As pointed out, the curriculum for each student did not always build upon the previous year’s learning. “One handicap to effective teaching was the fact that it might happen no two pupils were equally advanced in their studies.”19

Also, the quality of instruction in district schools varied widely, in part because the schoolmasters’ teaching credentials in some schools may have been little more than “see one, do one, teach one.” In 1826, James G. Carter, a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, reported: “The teachers of the primary summer schools have rarely had any education beyond what they have acquired in the very schools where [Page 7]they begin to teach.”20 Butts and Cremin note: “Little or no training was thought necessary for the post of teacher.”21 In his book, Old-Time Schools and School Books, author Clifton Johnson agreed:

Generally the teacher was young, sometimes not more than sixteen years old ; but if he was expert at figures, if he could read the Bible without stumbling over the long words, if he could write well enough to set a decent copy, if he could mend a pen, if he had vigor enough of character to assert his authority, and strength enough of arm to maintain it, he would do.22

Edward E. Gordon and Elaine H. Gordon give a more critical account. “Parents often lacked the knowledge or experience to hire good teachers. A report on schoolmasters in Illinois and Missouri during the 1830s stated that one-third were public nuisances due to incompetence or immorality, one-third did as much harm as good, and only about one-third were of some use in teaching basic literacy.”23 Whether the upstate New York district school system suffered from similar weaknesses during the previous decades is undocumented.

Born in 1809, Abraham Lincoln experienced frontier schooling after his family moved to Spencer County, Indiana, in 1817. He later described his experience: “There I grew up. There were some schools, so called, but no qualification was ever required of a teacher beyond “readin’, writin’, and cipherin’” to the Rule of Three. If a straggler supposed to understand Latin happened to sojourn in the neighborhood he was looked upon as a wizard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course, when I came of age I did not know much.”24 Joseph Smith’s experience may have been better. But whether he attended district schools for five terms, fourteen terms (seven years), or more, the curriculum and teaching methodologies would have limited the learning experiences he would have encountered.

[Page 8]Opportunities to Learn Creative Writing and Composition

As a training ground for authors to learn how to write long, complex books, Joseph Smith’s local schools provided few opportunities. Although author William L. Davis declares that Joseph Smith’s schooling included instruction in “basic rhetoric [and] composition,” available historical accounts do not support such claims.25 Creative writing and written composition assignments were not part of the education curriculums of district schools until decades later. “The great majority of the one-room elementary schools which sprang up over America in the early nineteenth century,” write Butts and Cremin, “were simple institutions providing a simple educational fare.”26 These schools “stressed basic reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, and often geography and history.”27

If paper and ink were available, a teacher might introduce short composition assignments to their pupils, but paper was expensive in the 1820s and could be difficult to acquire.28 Harry G. Good explains:

Excepting only arithmetic and handwriting, all subjects were taught through oral recitations. Reading, spelling, grammar, and, when they were later introduced, history and geography were recited orally. This was partly owing, no doubt, to the cost of paper. The almost exclusive use of the oral method had an unfortunate effect upon the whole curriculum. When pupils had mastered the simplest mechanics of reading, the recitation was conducted by having each one read a paragraph or stanza aloud until the entire lesson had been read. Often there was no attention to the meaning of the passage or even of the new words … Subjects such as grammar or geography were taught by an oral question-and-answer method based upon the words of the book. Nearly everything that was taught in the old school was taught from a book, and taught not by discussion.29

In an 1829 publication, schoolteacher Samuel R. Hall related how he asked a parent, “Will you take this little paper for your children? It will [Page 9]cost but a dollar.” The father replied, “No, I am not able.” Hall persisted, “But I am persuaded you will find it a very great benefit to your family, and you may contrive to save the amount in some way, by curtailing expenses less necessary.” The father replied: “I should be glad to take it, but I am in debt, and I cannot.”30

Chalk and hand-held slates were also relatively rare in American schools in the early 1800s. Dennis A. Wright and Geoffrey A. Wright note: “Schools in the nineteenth century provided students with few if any school supplies and rarely had blackboards. Slates were not introduced in the classroom until about 1820, and lead pencils were not used until several years later.”31 Harry G. Good adds: “About 1817 the blackboard was introduced at West Point, Dartmouth, and other colleges. Twenty years later it was still unusual in the primary schools of Massachusetts.”32

As a youth, Lincoln also lacked paper even to practice math calculations. Resourcefully, he “used to write his arithmetic sums on a large wooden shovel with a piece of charcoal. After covering it all over with examples, he would take his jack-knife and whittle and scrape the surface clean, ready for more ciphering. … Sometimes when the shovel was not at hand, he did his figuring on the logs of the house walls and on the doorposts, and other woodwork that afforded a surface he could mark on with his charcoal.”33

When paper was scarce, students used available supplies to practice penmanship, spelling, vocabulary, and perhaps how to write a letter. Most didactic exercises involved verbal repetition. Robert Connors, author of Composition-Rhetoric: Backgrounds, Theory, and Pedagogy, explains:

The essential difference between rhetoric courses and composition courses, most simply, became that in composition students had to do more than answer questions based on lecture or treatise. Composition was ineluctably practical; students were expected to write. Composition books, unlike rhetoric texts, could not make do merely with the oral [Page 10]questions and answers of a discipline whose product hung in the air and vanished.34

The first academic book teaching composition was not published in the United States until 1827, and it was designed for college classes.35 Few, if any, of the teachers in district schools would have been trained in composition. If the instructors possessed such skills, they probably would have sought better-paying jobs elsewhere.

Joseph Smith’s Pre-1829 Writing Projects

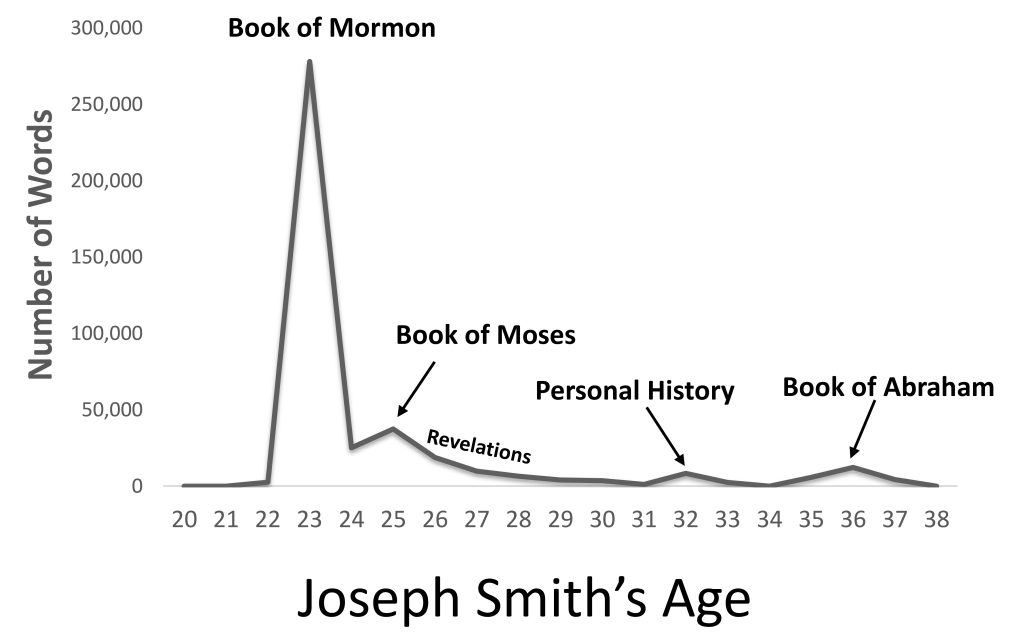

Joseph Smith participated in several writing projects prior to dictating the Book of Mormon. Among them are three revelations in the Doctrine and Covenant, the current section three (345 words) given July 1828, section four (150 words) given February 1829, and section five (1019 words) given the next month.36 Since original manuscripts do not exist, whether Joseph Smith wrote these or dictated them to a scribe is unclear. In addition, he also recited the now-lost manuscript of the Book of Lehi early in 1828 and may have penned one or two letters before April 7, 1829.37 Figure 2 charts Joseph’s known writing experiences, and shows very little occurring before he recited the Book of Mormon.

New England Educational Environment

Joseph Smith lived in an area with bookstores and libraries that contained hundreds of volumes available for viewing and research.38 Although their internal documents and local recollections fail to describe him visiting them, Orsamus Turner recalled: “Once a week he [Joseph Smith Junior] would stroll into the office of the old Palmyra Register, for his father’s [Page 11]paper.”39 The Palmyra Register was published between 1817 and 1821, indicating that Joseph would have been between eleven and fourteen.

Figure 2. Chart showing Joseph Smith’s lack of authoring experience before dictating the Book of Mormon at age twenty-three.

A few of Joseph Smith’s acquaintances refer to him as an avid reader, including Pomeroy Tucker, who wrote in 1867:

Joseph, moreover, as he grew in years, had learned to read comprehensively, in which qualification he was far in advance of his elder brother, and even of his father; and this talent was assiduously devoted, as he quitted or modified his idle habits, to the perusal of works of fiction and records of criminality, such for instance as would be classed with the “dime novels” of the present day. The stories of Stephen Burroughs and Captain Kidd, and the like, presented the highest charms for his expanding mental perceptions.40

Likewise, Philetus B. Spear recalled that in his youth, Joseph possessed a few novels and had a “copy of the ‘Arabian Nights.’”41 Another Palmyra resident recollected in 1876 that Joseph Smith spent his time “reading [Page 12]bad novels.”42 In contrast, his mother, Lucy Mack Smith recalled that Joseph “seemed much less inclined to the perusal of books than any of the rest of our children.”43

Joseph Smith’s 1829 Knowledge of the King James Bible

Lucy Mack Smith also quoted a youthful Joseph saying: “I can take my Bible, and go into the woods, and learn more in two hours, than you can learn at meeting in two years, if you should go all the time.”44 But she also noted that by 1823 Joseph had “never read the Bible through in his life.”45

John Stafford, who grew up with the Smiths in Manchester, recalled that the Smith family “studied the Bible” in their home school.46 Pomeroy Tucker provided this description:

As he [Joseph Smith] further advanced in reading and knowledge, he assumed a spiritual or religious turn of mind, and frequently perused the Bible, becoming quite familiar with portions thereof, both of the Old and New Testaments; selected texts from which he quoted and discussed with great assurance when in the presence of his superstitious acquaintances. The Prophecies and Revelations were his special forte. His interpretations of scriptural passages were always original and unique, and his deductions and conclusions often disgustingly blasphemous, according to the common apprehensions of Christian people.47

Here Tucker announces that Joseph Smith was “quite familiar with portions” of the Bible in the 1820s. Still, Tucker also seems to be embellishing because he adds: “The final conclusion announced by him [Joseph Smith] was, that … the Bible [was] a fable.”48 Joseph taught that the Bible is “the word of God as far as it is translated correctly” (Articles of Faith 8), raising questions regarding the reliability of Tucker’s other claims.

[Page 13]Despite his reported Biblical studies, David Whitmer remembered that “Smith was ignorant of the Bible at the time of the dictation.”49 Similarly, Emma Smith told Edmund C. Briggs in 1856 that Joseph “had such a limited knowledge of history at that time that he did not even know that Jerusalem was surrounded by walls.”50 Years later, in 1877, Emma repeated the story to Nels Madsen and Parley P. Pratt Jr.: “He had not read the Bible enough to know that there were walls around Jerusalem.”51

Joseph Smith’s Oratorical Abilities

Critics sometimes describe Joseph Smith as writing the Book of Mormon.52 In contrast, the historical record shows that between April and June of 1829, he recited 6,852 lengthy sentences to scribes and immediately published them as the 1830 Book of Mormon. Since then, none of the sentences have been fully edited or repositioned in the text.53 The historical record shows that Joseph Smith’s first oral draft was surprisingly refined from an editing standpoint.

[Page 14]The literary value of Joseph Smith’s dictation has also been recognized by non-Latter-day Saint scholars. “The Book of Mormon is the masterpiece of a most uncommon common man,” writes Washington University Professor Kenneth Winn. “The Book of Mormon is a seminal work.”54 More recently, Yale University Chair of History Daniel Walker Howe wrote: “The Book of Mormon should rank among the great achievements of American literature, but it has never been accorded the status it deserves.”55 In 1980, Gordon S. Wood, who would win the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for History, described it frankly: “The Book of Mormon is an extraordinary work of popular imagination and one of the greatest documents in American cultural history.”56

No Formal Oratorical Training

Such assessments support that Joseph Smith possessed advanced oratorical abilities in 1829, but how and when he developed them is unclear.57 His ability to verbalize a refined narrative like the 1830 Book of Mormon demonstrated rhetorical capabilities generally developed through practice. The authors of the high school textbook, Speech, explain: “The key is to practice. Only through practice can you begin to feel comfortable with the pressure of such limited time to prepare.”58 Also, University of Wisconsin Professor Harold Scheub, clarifies: “Doubtless the most significant single characteristic of oral narrative performance is repetition, in a variety of forms. The repetition of words, of phrases, of full images, and finally of complete narratives.”59 Despite such expectations, no one recalled Joseph Smith practicing for the Book of Mormon recitation. Richard Bushman reports that Joseph “was not [Page 15]an eloquent preacher; he is not known to have preached a single sermon before the organizing the Church in 1830.”60

Similarly, the district school curriculum in the 1820s actively employed verbal repetition to teach grammar, vocabulary, and Biblical studies. Another form of oral instruction, “speaking of pieces,” required the student to stand before the class and recite a short discourse or memorized narration.61 However, extemporaneous speaking exercises, those that prepared a student to verbalize ideas composed on-the-spot or from previously memorized outlines, were not included. Despite this deficiency, the historical record describes other extracurricular activities that might have improved Joseph Smith’s oratorical skillset.

Telling Stories to Family in 1823

Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph’s mother, describes his storytelling inclinations around 1823 when he was in his seventeenth year:

During our evening conversations, Joseph would occasionally give us some of the most amusing recitals that could be imagined. He would describe the ancient inhabitants of this continent, their dress, mode of travelling, and the animals upon which they rode; their cities, their buildings, with every particular; their mode of warfare; and also their religious worship. This he would do with as much ease, seemingly, as if he had spent his whole life with them.62

If Joseph’s stories originated in his imagination, this recollection is evidence of his creativity as a youth. They include references to the “ancient inhabitants of this continent,” including “their dress, mode of traveling, and the animals upon which they rode,” details not included in the narrative of the Book of Mormon. Although Lucy mentioned that Joseph spoke only occasionally, these family recitations could represent the tip of his expanding imagination iceberg and his attempts to hone oratorical skills. If so, other family members or acquaintances might have remembered, but only Lucy left a record. Joseph’s younger brother William later claimed that Joseph was incapable of authoring a “historey of a once enlightned people, their rise their progress, their origin, and [Page 16]their final over throw that once inhabited this american Continent.”63 William’s statement seems to contradict Lucy’s recollection or suggests that Joseph’s recitals did not include such details or did not impress all family members.

If imaginative tales commonly rolled from Joseph’s lips, or creative storytelling became a pastime as he prepared his mind and oratory skills for the 1829 Book of Mormon dictation, no one outside the family recalled him actively rehearsing.64 In 1834, Eber D. Howe published statements from twenty-two local residents and two “group statements” from the inhabitants of Palmyra and Manchester.65 In July 1880, newspaperman Frederick G. Mather compiled written recollections from twelve citizens of Susquehanna, Broome, and Chenango Counties, Pennsylvania.66 In 1888, Arthur Deming printed accounts from fourteen individuals in two volumes of Naked Truths about Mormonism.67 Many of these persons [Page 17]knew Joseph Smith Jr. personally, but none describe him engaging in the activities of a village bard or entertaining spectators with his recitals. Journalist James Gordon Bennett visited the Palmyra area in August of 1831 and recorded that Joseph Smith’s father was a “great story teller,” but wrote nothing similar concerning the younger Joseph.68

Involvement as a Debater and Exhorter

As he attended religious meetings and camp gatherings as a youth, Joseph Smith witnessed a variety of sermonizing. At times he may have participated as a lay member of the audience. In 1893, Daniel Hendrix recalled that Joseph “was a good talker and would have made a fine stump-speaker if he had had the training.”69According to several sources, Joseph Smith attended Methodist meetings but never joined the church. Pomeroy Tucker wrote:

Protracted revival meetings were customary in some of the churches, and Smith frequented those of different denominations, sometimes professing to participate in their devotional exercises. At one time he joined the probationary class of the Methodist church in Palmyra, and made some active demonstrations of engagedness, though his assumed convictions were insufficiently grounded or abiding to carry him along to the saving point of conversion, and he soon withdrew from the class.70

In 1851, Orsamus Turner remembered that Joseph Smith “was a very passable exhorter” at Methodist camp meetings.71 Joseph’s informal involvement with the Methodists lasted just a few months, from the fall of 1824 to the winter of 1825.72 As a nonmember exhorter who spoke impromptu during Methodist meetings, he would have received little or no formal oratorical training compared to that offered to exhorters with full membership. Turner also reported:

Joseph had a little ambition; and some very laudable aspirations; the mother’s intellect occasionally shone out in [Page 18]him feebly, especially when he used to help us solve some portentous questions of moral or political ethics, in our juvenile debating club, which we moved down to the old red school house on Durfee street.73

Here Turner describes Joseph Smith as a competent debater but attributes the ability to his “mother’s intellect” when it “shone out in him feebly.” Overall, Turner seemed unimpressed with the youthful Joseph: “He was lounging, idle; (not to say vicious,) and possessed of less than ordinary intellect. The author’s own recollections of him are distinct ones.”74 Had Joseph distinguished himself as a highly-skilled debater or exhorter, Turner might have spoken of him more favorably.75

Recollections of Joseph Smith’s Public Speaking Skills

Other references to Joseph Smith’s oratory skills before and after 1829 are generally uncomplimentary. Jared Carter remembered him in the early 1830s as “not naturally talented for a speaker.”76 Similarly, a newspaper reporter in 1843 penned: “He is a bad speaker, and appears to be very imperfectly educated.”77 Peter H. Burnett, who was Joseph’s lawyer in Missouri, and later governor of California, recalled: “His appearance was not prepossessing, and his conversational powers were but ordinary. You could see at a glance that his education was very limited. He was an awkward but vehement speaker. In conversation he was slow, and used [Page 19]too many words to express his ideas, and would not generally go directly to a point.”78 Lorenzo Snow remembered: “Joseph Smith was not what would be called a fluent speaker. He simply bore his testimony.”79

Joseph Smith’s Pre-1829 Educational Opportunities

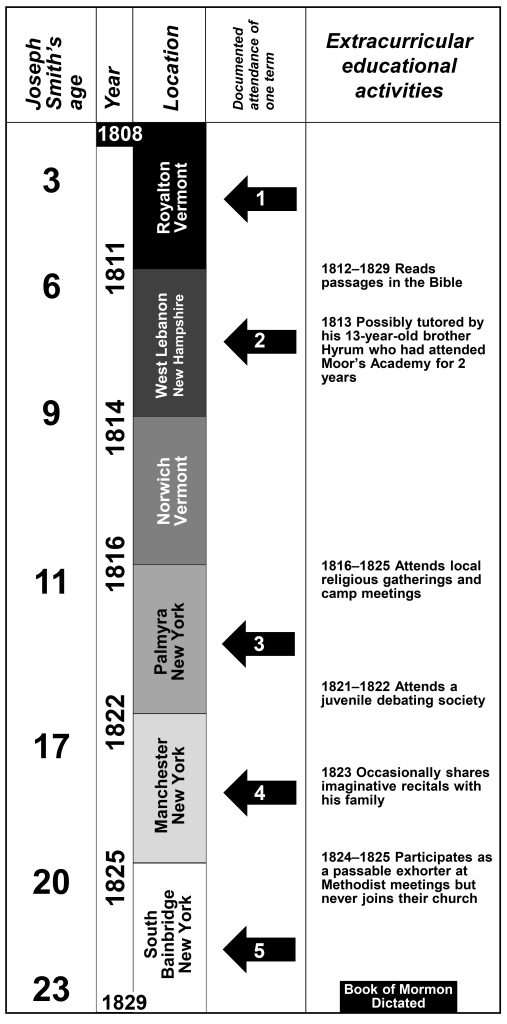

To summarize, besides his time spent in district school classrooms, Joseph Smith’s education was supplemented by at least six extracurricular educational activities:

| 1812–1829: | Learning about and reading the Bible |

| 1813: | Hyrum Smith’s possible tutoring at age seven |

| 1816–1825: | Participation in local religious meetings |

| 1821–1822: | Attends the juvenile debate club |

| 1823: | Occasionally shares imaginative stories with his family |

| 1824–1825: | Passable exhorter at Methodist meetings |

While additional opportunities for pre-1829 training, education, or experience as an author or orator may have been available to Joseph Smith, none are detailed in the historical record (see Figure 3).

[Page 20]

Figure 3. Timeline showing Joseph Smith’s age when he may have experienced schooling and other formal educational experiences.

Joseph Smith’s Later Education

Although no teacher before 1829 remembered Joseph Smith’s aptitudes as a student, three later instructors recalled his abilities as they taught him during the mid-1830s.

William McLellin Recalls Joseph Smith’s 1834 Knowledge Base

Years after his excommunication, William McLellin penned:

I was personally and intimately acquainted with Joseph Smith <the man who read off the> the translation of the book, for five years near the beginning of his ministry. He attended my High school during – <the winter> of 1834. He attended my school and learned science all winter. I learned the strength of his mind as <to> the study and principles of science. Hence I think I knew him. And I here say that he had one of <the. Strongest, well balanced, penetrating, and retentive minds of any <man> with which <whom> I ever formed an acquaintance, among the thousands of my observations. [Page 21]Although when I took him into my school, he was without scientific knowledge or attainments.80

Five years after dictating the Book of Mormon, McLellin acknowledged Joseph Smith’s remarkable learning ability but stated he was then “without scientific knowledge.” Early definitions of “science” equate it with general knowledge rather than limiting it to a specific genre.81 So McLellin’s comment described Joseph Smith’s depth of knowledge in 1834 as limited. Neither did McLellin believe that Joseph authored the Book of Mormon. Calling it a “divine record,” McLellin cautioned James T. Cobb in 1880:

When a man goes at the Book of M[ormon] he touches the apple of my eye. He fights against truth—against purity—against light—against the the [sic] purist, or one of the truest, purist books on earth. I have more confidence in the Book of Mormon than any book of this wide earth! And its not because I don’t know its contents, for I probably have read it through 20 times … It must be that a man does not love purity when he finds fa[u]lt with the Book of Mormon!!82

Believing Joseph Smith was “the man who read off” the Book of Mormon rather than its author, McLellin continued his admiration for the book after leaving the Saints.

Chauncey Webb: Joseph Smith’s 1834 Grammar Teacher

Another Kirtland teacher, Chauncey G. Webb, followed the Saints to Nauvoo and to Utah but later apostatized. According to an account printed by an antagonistic reporter, Webb stated:

Joseph was the calf that sucked three cows. He acquired knowledge very rapidly . . . He learned by heart a number of Latin, Greek and French common-place phrases, to use them in his speeches and sermons. For instance: Vox populi, vox diaboli; or Laus Deus or amor vincet omnium, as quoted in [Page 22]the Nauvoo “Wasp” … I taught him the first rules of English Grammar in Kirtland in 1834. He learned rapidly.83

While Webb may have been exaggerating, he too remembered Joseph Smith’s impressive 1834 learning aptitude, but also states he taught Joseph “the first rules of English Grammar in Kirtland in 1834.” It is unclear how Joseph Smith could dictate the Book of Mormon with its 269,320 words and nearly 7000 sentences in 1829 without knowing more than the “first rules of English Grammar.”

Joshua Seixas as Joseph Smith’s Hebrew Teacher

The Church hired the third teacher, Joshua Seixas, in 1836 to teach Hebrew to forty students over seven weeks beginning on January 26. Historians compiling The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 5 explain:

By all accounts, JS [Joseph Smith] was a diligent student of Hebrew. After Oliver Cowdery returned to Kirtland with “a quantity of Hebrew books” on November 20, 1835, JS commenced an earnest study of the language. Though he participated in the formal classes taught by Seixas, he also devoted considerable time to studying the language on his own. Between November 23, 1835, and March 29, 1836, JS’s journal mentions his studying of Hebrew—whether in class, with colleagues, or by himself—no fewer than seventy times.84

Matthew Grey also notes: “In addition to attending his regular classes, Joseph asked Seixas for private study sessions, worked ahead on translation assignments, reviewed lessons on Sundays, and studied when he was sick.”85 After completing the class on March 30, Seixas issued Joseph Smith a certificate:

[Page 23]Mr Joseph Smith Junr has attended a full course of Hebrew lessons under my tuition; & has been indefatigable in acquiring the principles of the sacred language of the Old Testament Scriptures in their original tongue. He has so far accomplished a knowledge of it, that he is able to translate to my entire satisfaction; & by prosecuting the study he will be able to become a proficient in Hebrew.86

Here Seixas certifies that Joseph Smith exerted “indefatigable” efforts to learn Hebrew and that Joseph could translate to his “entire satisfaction.” But Seixas also declares that Smith will become “proficient” only if he continues “prosecuting the study” of the language. In contrast, the twenty-four-year-old Orson Pratt also attended the Hebrew lessons and was the only other student known to receive a certificate: “During the winter I attended the Heb. School about 8 weeks in which time I made greater progress than what I could have expected in so short a period. I obtained a certificate from J. Seixas, our instructor, certifying to my capability of teaching that language.”87 By many standards, Orson Pratt was a genius, and this episode supports Pratt bested Joseph Smith, at least when learning Hebrew.88

Joseph Smith’s Memory

Joseph Smith’s attempt to learn Hebrew provides a glimpse into his ability to memorize.89 As Professors Elvira V. Masoura and Susan E. Gathercole note: “Research has revealed a close link between language acquisition and the capacity of the verbal component of working memory.”90 Had Joseph possessed a photographic or eidetic memory, he would likely have progressed more rapidly and surpassed other students like Orson Pratt.91

[Page 24]No Recollections that Joseph Smith was “Educated”

While scattered positive references to Joseph Smith’s intellect are available, virtually all mentioning his 1829 abilities are negative, and none refer to him as “educated.” The earliest reference to his literary competence was published in August 1829, months before the Book of Mormon was printed. Jonathan A. Hadley reflected insider knowledge as he described details of the coming forth and translation of the gold plates and then referred to Joseph Smith as “very illiterate.”92 Similarly, months before his June 16, 1831, baptism into the Church, W. W. Phelps affirmed: “I am acquainted with a number of the persons concerned in the publication, called the ‘Book of Mormon.’—Joseph Smith is a person of very limited abilities in common learning.”93 E. D. Howe wrote in his 1834 publication Mormonism Unvailed: “That the common advantages of education were denied to our prophet, or that they were much neglected, we believe to be a fact.”94 Just a year after the Book of Mormon was published, the Palmyra Reflector reported that Joseph Smith’s “mental powers appear to be extremely limited, and from the small opportunity he has had at school, he made little or no proficiency.”95 Likewise, Isaac Hale recounted in 1834: “I first became acquainted with Joseph Smith, Jr. in November, 1825 … His appearance at this time, was that of a careless young man—not very well educated.”96 Other statements describe Joseph Smith as ignorant97 or illiterate.98

In an 1875 account, Joseph’s brother William specifically addressed Joseph’s abilities in the 1820s:

[Page 25]It is to be remembered that Joseph Smith was only 17 years of age when he first first began his profesional career in the Minestrey. That he was illitterate to some extent is admitted but that he was enterly [entirely] unlettered is a mistake. In Sintax, orthography Mathamatics grammar geography with other studies in the Common Schools of his day he was no novis and for writing he wrote a plain intelegable hand.99

William refers to Joseph as “no novis,” regarding syntax (sentence formation), orthography (spelling), mathematics, grammar, and geography. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a novice as “an inexperienced person; one who is new to the circumstances in which he is placed; a beginner.”100 William does not specify how far (in his recollection) Joseph had advanced beyond novice or beginner. But William also states that Joseph was then “illiterate to some extent,” suggesting his progress was limited.

Similarly, Emma Smith stated in 1879 that at the time of the Book of Mormon dictation, Joseph “could neither write nor dictate a coherent and well-worded letter.”101 Martin Harris also recalled that at the time, Joseph “could not spell the word February.”102 David Whitmer described Joseph as “a man of limited education and could hardly write legibly.”103

Joseph Smith recalled he was “deprived of the benefit of an education … I was merely instructed in reading, writing and the ground rules of arithmetic.”104 Biographer Richard Bushman estimated that Joseph “had less than two years of formal schooling.”105

John H. Gilbert, who typeset the Book of Mormon, remembered in 1881: “We had a great deal of trouble with it [the Book of Mormon manuscript]. It was not punctuated at all. They [Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery] did not know anything about punctuation.” When [Page 26]asked: “Was he [Joseph Smith] educated?” he responded: “Oh, not at all then.”106

Sylvia Walker, who attended school with Joseph’s brother William Smith, recalled that he and the other children were “very poor scholars.”107 Able Chase reported in 1881 that the Smiths “were poorly educated, ignorant and superstitious.”108 None of Joseph Smith’s classmates remembered him as a star student, an avid learner, or as intellectually gifted.109

In an 1899 article, “The Origin of the ‘Book of Mormon,” published in American Anthropologist, Perry Benjamin Pierce summed up his research:

Joseph Smith Jr was at the time [of the Book of Mormon publication] twenty-four years of age. He was, according to some authorities, unable to read or write; by others it is asserted that while able to read and write to some extent he did so with difficulty. By no authority is it contended that he was in any respect more than very poorly educated . . . [He was] an uneducated, uncultivated, country boor of equivocal reputation and low origin.110

Contemporaries React to Joseph Smith as Author

When later asked how Joseph Smith created all the words of the Book of Mormon, several of his contemporaries speculated differently. In an [Page 27]1879 conversation with Joseph’s brother-in-law Michael Morse (who married Emma’s sister Tryal), an interviewer related:

[Michael Morse] states that he first knew Joseph when he came to Harmony, Pa., an awkward, unlearned youth of about nineteen years of age . . . He further states that when Joseph was translating the Book of Mormon, he, (Morse), had occasion more than once to go into his immediate presence, and saw him engaged at his work of translation …

[When asked] whether Joseph was sufficiently intelligent and talented to compose and dictate of his own ability the matter written down by the scribes. To this Mr. Morse replied with decided emphasis, No. He said he [Morse] then was not at all learned, yet was confident he had more learning than Joseph then had.

[When asked] how he (Morse) accounted for Joseph’s dictating the Book of Mormon in the manner he had described. To this he replied he did not know. He said it was a strange piece of work, and he had thought that Joseph might have found the writings of some good man and, committing them to memory, recited them to his scribes from time to time.

We suggested that if this were true, Joseph must have had a prodigious memory — a memory that could be had only by miraculous endowment. To this Mr. Morse replied that he, of course, did not know as to how Joseph was enabled to furnish the matter he dictated.111

John H. Gilbert, the typesetter, similarly related:

Was he [Joseph Smith] educated, do you know?

“Oh, not at all then; but I understand that afterwards he made great advancement, and was quite a scholar and orator.”

How do you account for the production of the Book of Mormon, Mr. Gilbert, then, if Joseph Smith was so illiterate?

“Well, that is the difficult question. It must have been from the Spaulding romance–you have heard of that, I suppose. The parties here then never could have been the authors of [Page 28]it, certainly. I have been for the last forty-five or fifty years trying to get the key to that thing; but we have never been able to make the connecting yet. For some years past I have been corresponding with a person in Salt Lake, by the name of Cobb, who is getting out a work against the Mormons; but we have never been able to find out what we wanted.”112

In 1881, Manchester neighbor John Stafford recalled:

If young Smith was as illiterate as you say, Doctor, how do you account for the Book of Mormon?

“Well, I can’t; except that Sidney Rigdon was connected with them.”

What makes you think he was connected with them?

“Because I can’t account for the Book of Mormon any other way.”

Was Rigdon ever around there before the Book of Mormon was published?

“No; not as we could ever find out.”113

Similarly, when asked if her husband could author the Book of Mormon, Emma Smith replied: “Though I was an active participant in the scenes that transpired, it is marvelous to me, ‘a marvel and a wonder,’ as much so as to any one else.”114 Hiram Page, one of the Eight Witnesses of the Book of Mormon who left the Church in 1838, wrote in 1847: “As to the book of Mormon, it would be doing injustice to myself … to say that a man of Joseph’s ability, who at that time did not know how to pronounce the word Nephi, could write a book of six hundred pages, as correct as the book of Mormon.”115

These assessments from individuals personally acquainted with Joseph Smith question whether he could not have authored the Book of Mormon. Michael Morris believed Joseph memorized someone else’s writings, Gilbert supported the Spalding theory, John Stafford blamed Sidney Rigdon, and Emma Smith and Hiram Page implied supernatural assistance.

[Page 29]Joseph Smith was Intelligent but Minimally Educated in 1829

The discussion above is not designed to portray Joseph Smith as illiterate or unintelligent in 1829 or at any time. McLellin and Webb commented on his intelligence, and multiple later accounts agree. Lawyer John S. Reed, who defended him in trials in Chenango and Broome counties in 1830, recalled in 1844: “He [Joseph Smith] was often spoken of as a young man of intelligence, and good morals, and possessing a mind susceptible of the highest intellectual attainments.”116 Baptized in 1840, Howard Coray, who knew Joseph in Nauvoo, remembered:

The Prophet had a great many callers or visitors, and he received them in his office where I was clerking, persons of almost all professions, doctors, lawyers, priests and people seemed anxious to get a good look at what was then considered something very wonderful: a man who should dare to call himself a prophet and announce himself as a seer and ambassador of the Lord. Not only were they anxious to see, but also to ask hard questions, in order to ascertain his depth. Well, what did I discover? … He was always equal to the occasion, and perfectly master of the situation; and possessed the power to make everybody realize his superiority, which they evinced in an unmistakable manner. I could clearly see that Joseph was the captain, no matter whose company he was in, knowing the meagerness of his education, I was truly gratified at seeing how much at ease he always was, even in the company of the most scientific, and the ready off-hand manner in which he would answer their questions.117

Similarly, Parley P. Pratt, who met Joseph Smith in 1830 and later became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, penned in 1853: “His [Joseph Smith’s] intelligence [was] universal, and his language abounding in original eloquence peculiar to himself—not polished—not studied—not smoothed and softened by education and refined by art; [Page 30]but flowing forth in its own native simplicity, and profusely abounding in variety of subject and manner.”118

Alternatively, the primary focus of this paper is to demonstrate the problem with secularist theories that portray Joseph Smith as intellectually capable of producing the Book of Mormon using his 1829 cognitive abilities. That he dictated every word to scribes is well documented historically.119 And based on that evidence, skeptics could then declare that he must have had the natural intelligence and abilities to accomplish the feat. For example, in 2019, Eran Shalev, chair of the history department at Haifa University, wrote: “Historians have long denied Smith the image of an ignorant rural boy who could not have acquired all the material that he would have needed to write The Book of Mormon.”120 But the case is more complex because little or no manuscript data (beyond the historical artifacts of the Original and Printer’s manuscripts of the Book of Mormon) supports Joseph Smith’s capacity to do so.121

Undaunted by this limitation, empiricists often speculate about when and where Joseph Smith supposedly gained the knowledge and training he would have needed to dictate a lengthy, complex, and refined book. However, among scholars, a theory derived almost exclusively from speculations will generally be less persuasive. If it contradicts the vast majority of available documentary evidence, its credibility should diminish further.

[Page 31]Ironically, the popularity of Joseph Smith’s intellect theory continues among many observers today despite the lack of historical data supporting it. Whether evidentiary transparency can expose its weaknesses enough to impact its acceptance by skeptics remains to be seen.

Go here to see the 11 thoughts on ““Joseph Smith’s Education and Intellect as Described in Documentary Sources”” or to comment on it.