Abstract: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw compares Moses’ tabernacle and Noah’s ark, and then identifies the story of Noah as a temple related drama, drawing of temple mysticism and symbols. After examining structural similarities between ark and tabernacle and bringing into the discussion further information about the Mesopotamian flood story, he shows how Noah’s ark is a beginning of a new creation, pointing out the central point of Day One in the Noah story. When Noah leaves the ark, they find themselves in a garden, not unlike the Garden of Eden in the way the Bible speaks about it. A covenant is established in signs and tokens. Noah is the new Adam. This is then followed by a fall/Judgement scene story, even though it is Ham who is judged, not Noah. In accordance with mostly non-Mormon sources quoted, Bradshaw points out how Noah was not in “his” tent, but in the tent of the Shekhina, the presence of God, how being drunk was seen by the ancients as a synonym to “being caught up in a vision of God,” and how his “nakedness” was rather referring to garments God had made for Adam and Eve.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “The Ark and the Tent: Temple Symbolism in the Story of Noah,” in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 22 September 2012, ed. William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), [Page 94]25–66. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/temple-insights/.]

It has long been recognized that the story of Noah recapitulates the Genesis accounts of the Creation, the Garden, and the Fall of Adam and Eve. What has been generally underappreciated by modern scholarship, however, is the nature and depth of the relationship between all these stories and the liturgy and layout of temples, not only in Israel but also throughout the ancient Near East. And this relationship goes two ways. Not only have accounts of primeval history been included as a significant part of ancient temple worship, but also, in striking abundance, themes echoing temple architecture, furnishings, ritual, and covenants have been deeply woven into scripture itself.

In this chapter I will outline some of the rich temple themes in the biblical account of the great flood, highlighting how the scriptural descriptions of the structure and function of the ark and the tent within the story of Noah anticipate the design and purpose of the later tabernacle of Moses.

Structural Similarities Between the Ark and the Tabernacle

It is significant that, apart from the tabernacle of Moses1 and the temple of Solomon,2 Noah’s ark is the only man-made structure mentioned in the Bible whose design was directly revealed by God.3

Like the tabernacle, Noah’s ark “was designed as a temple.”4 The ark’s three decks suggest both the three divisions of the tabernacle and the threefold layout of the Garden of Eden.5 Indeed, each of the three decks of Noah’s ark was exactly “the same height as the Tabernacle and three times the area of the Tabernacle court.”6 Strengthening the association between the Ark and the Tabernacle is the fact that the Hebrew term for Noah’s ark, tevah, later became the standard word for the ark of the covenant in Mishnaic Hebrew.7 In addition, the Septuagint used the same Greek term, kibotos, for both Noah’s ark and the ark of the covenant.8 The ratio of the width to the height of both of these arks is 3:5.9

Marking the similarities between the shape of the ark of the covenant and the chest-like form of Noah’s ark, Westermann describes Noah’s ark as “a huge, rectangular box, with a roof.”10 The biblical account makes it clear that the ark “was not shaped like a ship and it had no oars,” “accentuating the fact that Noah’s deliverance was not dependent [Page 95]on navigating skills, [but rather happened] entirely by God’s will,”11 its movement solely determined by “the thrust of the water and wind.”12

Consistent with the emphasis on deliverance by God rather than through human navigation, the Hebrew word for “ark” reappears for the only other time in the Bible in the story of the infant Moses, whose deliverance from death was also made possible by a free-floating watercraft — specifically, in this case, a reed basket.13 Reeds may have also been used as part of the construction materials for Noah’s ark, as will be discussed below.

Besides the resemblances in form between the Ark and the Tabernacle, there is also the manner by which the Ark was entered and exited. For example, scholars have noted in the Mesopotamian flood story of Gilgamesh a similarity of the loading of the ship to the loading of goods into a temple.14 Morales discusses the centrality of entering and leaving the Ark as reason “to suspect an entrance liturgy ideal at work,”15 with all “‘entries’ as being via Noah,”16 the righteous and unblemished priestly prototype.17

As for the material out of which the ark was constructed, Genesis 6:14 reads, “Make thee an ark of gopher wood; rooms shalt thou make in the ark, and shalt pitch it within and without with pitch.”

The meaning of the Hebrew term for “gopher wood” — unique in the Bible to Genesis 6:14 — is uncertain.18 Modern commentators often take it to mean cypress wood.19 Because it is resistant to rot, the cypress tree was used in ancient times for the building of ships.20

There is an extensive mythology about the cypress tree in cultures throughout the world. It is known for its fragrance and longevity21 — qualities that have naturally linked it with ancient literature describing the Garden of Eden.22 Cypress trees were also sometimes used to make temple doors — gateways to Paradise.23

The possibility of conscious rhyming wordplay in the juxtaposition of the Hebrew terms gopher and kopher (“pitch”) within the same verse cannot be ruled out. As Harper notes, the word kopher might have evoked for the ancient reader, “the rich cultic overtones of kaphar ‘ransom’ with its half-shekel temple atonement price,24 kapporeth ‘mercy seat’ over the Ark of the Covenant,25 and the verb kipper ‘to atone’ associated with so many priestly rituals.”26 Some of these rituals involve the action of smearing or wiping, the same movements by which pitch is applied.27 Just as God’s presence in the tabernacle preserves the life of His people, so Noah’s ark preserves a righteous remnant of humanity along with representatives of all its creatures.

[Page 96]In Mesopotamian flood stories, the construction materials for the building of a boat were obtained by tearing down a reed-hut. The basic construction idea of such huts is that poles of resinous wood would have framed and supported woven reed mats.28 The reed mats would be stitched to the hull and covered with pitch to make them waterproof.29 These building techniques are still in use today.

Although reed-huts may sometimes serve as secular enclosures, references to them in Mesopotamian flood stories clearly point to their ancient use as divine sanctuaries.30 Seated in his rectangular sanctuary made of reeds, Enki presided both as the god of wisdom and of the Abzu, the freshwater ocean that existed under the land.31 In some parts of the ancient Near East, mortal kings and priests entered into reed sanctuaries in order to commune with the gods, just as Israelite high priests entered their temples.

In a Mesopotamian account of the flood story, Ziusudra enters into a “reed-hut … temple,”32 where he stands “day after day” listening to the “conversation” of the divine assembly.33 Eventually, Ziusudra hears the deadly oaths of the council of the gods following their decision to destroy mankind by a devastating flood. Regretting the decision of the divine assembly, the god Enki contrives a plan to warn Ziusudra and to instruct him on how to build a boat that will save him and his family. Evoking ancient Near East parallels where the gods whisper their secrets to mortals standing on the other side of temple partitions or screens separating the divine and human realms,34 Enki conveys his warning message privately through the thin wall of Ziusudra’s reed sanctuary.35 Related accounts tell us that Enki instructed Ziusudra to tear down the reed-hut temple and to use the materials to build a boat.36

Three kinds of boat-building materials are listed in the Mesopotamian flood stories — wood timbers, reeds, and pitch.37 The biblical list is identical, except that the second item is given as “rooms” rather than “reeds.” Concluding “that the apparent lack of the reed-hut or primeval shrine in the Genesis flood account demands closer inspection,”38 Jason McCann observes39 that re-pointing the Hebrew vowels would lead to an alternate translation signifying an ark that was “woven-of-reeds.” Thus, the New Jerusalem Bible translation of Genesis 6:14:40 “Make yourself an ark out of resinous wood. Make it with reeds and caulk it with pitch inside and out” (emphasis added).

By a translation that recognizes “reeds,” not “rooms,” as the second element in the building materials for Noah’s ark, a puzzling inconsistency [Page 97]between the Bible and the Mesopotamian accounts is resolved while at the same time further connecting the scriptural ark with the temple.

Let’s now turn our attention to the Creation and temple themes in the story of the Flood, where we will find temple parallels not only to the structure of the Ark but also in its function.

Creation

In considering the role of Noah’s ark in the Flood story, it should be noted that it was, specifically, a mobile sanctuary,41 as were the tabernacle and the ark made of reeds that saved the baby Moses. Arguably, each of these structures can be described as a traveling vehicle of rescue designed to parallel in function God’s portable pavilion or chariot.

Scripture makes a clear distinction between the fixed heavenly temple and its portable counterparts. For example, in Psalm 1842 and D&C 121:1, the “pavilion” of “God’s hiding place” should not be equated with the celestial “temple” to which the prayers of the oppressed go up43 but rather as a representation of a movable “conveyance”44 in which God could swiftly descend to rescue His people from mortal danger.45 The sense of the action is succinctly captured by Robert Alter: “The outcry of the beleaguered warrior ascends all the way to the highest heavens, thus launching a downward vertical movement”46 of God’s own chariot.

Despite its ungainly shape as a buoyant temple, the Ark is portrayed as floating confidently above the chaos of the great deep. Significantly, the motion of the ark “upon the face of the waters”47 paralleled the movement of the Spirit of God “upon the face of the waters”48 at the original creation of heaven and earth. The deliberate nature of this parallel is made clear when we consider that Genesis 1:2 and 7:18 are the only two verses in the Bible that contain the phrase “the face of the waters.” In short, scripture intends to make us understand that in the presence of the Ark there was a return of the same Spirit of God that had hovered over the waters at the Creation — the Spirit whose previous withdrawal had been presaged in Genesis 6:3.49

The motion of the Ark “upon the face of the waters,”50 like the Spirit of God “upon the face of the waters”51 at Creation, was a portent of the (re)appearance of light and life. Within the Ark, a “mini replica of Creation,”52 were the last vestiges of the original Creation, “an alternative earth for all living creatures,”53 “a colony of heaven”54 containing seedlings for the planting of a second Garden of Eden,55 the nucleus of a new world — all hidden within a vessel of rescue described in scripture, like the tabernacle, as a likeness of God’s own traveling pavilion.

[Page 98]Just as the Spirit of God patiently brooded56 over the great deep at the Creation and just as “the longsuffering of God waited … while the ark was a preparing,”57 so the indefatigable Noah endured the long brooding of the ark over the slowly receding waters of the deluge58 until, at last, the dry land appeared.59

There are rich thematic connections between the emergence of the dry land at the Creation, the settling of the Ark atop the first mountain to emerge from the Flood, New Year’s Day, and the temple. In ancient Israel, the holiest spot on earth was believed to be the foundation stone in front of the ark of the covenant within the temple at Jerusalem:60 “It was the first solid material to emerge from the waters of Creation,61 and it was upon this stone that the Deity effected Creation.” The depiction of the ark-temple of Noah perched upon Mount Ararat would have evoked similar temple imagery for the ancient reader of the Bible.

Note that it was “in the six hundred and first year [of Noah’s life] in the first month, the first day of the month” that “the waters were dried up.”62 The specific wording of this verse would have hinted to the ancient reader that there was ritual significance to the date. Note that it was also the “first day of the first month”63 when the tabernacle was dedicated, “while Solomon’s temple was dedicated at the New Year festival in the autumn.”64

Garden

Nothing in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden can be understood without reference to the temple. Neither can the story of Noah and his family in the garden setting of a renewed earth be appreciated fully without taking the temple as its background.

Allusions to Garden of Eden and temple motifs begin as soon as Noah and his family leave the ark. Just as the book of Moses highlights Adam’s diligence in offering sacrifice as soon as he entered the fallen world,65 Genesis describes Noah’s first action on the renewed earth as being the building of an altar for burnt offerings.66 Likewise, in each account, God’s blessing is followed by a commandment to multiply and replenish the earth.67 Both stories also contain instructions about what the protagonists are and are not to eat.68

Notably, in each case a covenant is established in a context of ordinances and signs or tokens.69 More specifically, according to Pseudo-Philo,70 the rainbow as a sign or token of a covenant of higher priesthood blessings was said by God to be an analogue of Moses’s staff, a symbol of kingship.71

[Page 99]Both the story of Adam and Eve and the story of Noah prominently feature the theme of nakedness being covered by a garment.72 Noah, like Adam, is called the “lord of the whole earth.”73 Surely, it is no exaggeration to say that Noah is portrayed as a new Adam, “reversing the estrangement” between God and man by means of an atoning sacrifice.74

Fall and Judgment

In Genesis, the Fall and judgment scenes are straightforwardly recited as follows:75

And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard:

And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.

And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.

And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

Looking at the passage more closely, however, raises several questions. To begin with, what tent did Noah enter? Although the English translation says “his tent,” the Hebrew text features a feminine possessive that would normally mean “her tent.”76 The Midrash Rabbah explains this as a reference to the tent of Noah’s wife,77 and both ancient and modern commentators have often focused on this detail to imply that Ham intruded on his father and mother during a moment of intimacy.78

A very intriguing alternative explanation, however, is offered by Rabbi Shim’on in the Zohar, who takes the he of the feminine possessive to mean “‘the tent of that vineyard,’ namely, the tent of Shekhinah,”79 the term for “the divine feminine”80 that was equated to the presence of Yahweh in Israelite temples. In a variant of the same theme, at least one set of modern commentators takes the he as referring to Yahweh, hence reading the term as the “Tent of Yahweh,”81 the divine sanctuary.

[Page 100]In view of the pervasive theme in ancient literature where the climax of the Flood story is the founding of a temple over the source of the floodwaters, Blenkinsopp82 finds it “safe to assume” that the biblical account of “the deluge served … as the Israelite version of the cosmogonic victory of the deity resulting in the building of a sanctuary for him.” Lucian reports that “the temple of Hierapolis on the Euphrates was founded over the flood waters by Deucalion, counterpart of Ziusudra, Utnapishtim, and Noah.”83 Consistent with this theme, Psalms 29:10 “speaks of Yahweh enthroned over the abyss.”84

Given the many allusions in the story of Noah to the tabernacle of Moses, it would have been natural for the ancient reader to have seen in Noah’s tent, at the foot of the mount where the ark-temple rested, a parallel with the sacred “tent of meeting” at the foot of Mount Sinai, at whose top God’s heavenly tent had been spread.

How are we to understand the mention that Noah “was drunken”? Most rabbinical sources make no attempt to explain or justify but instead roundly criticize Noah’s actions.85 The difficulty with that explanation is the fact that the scriptures offer no hint of condemnation for Noah’s supposed drunkenness.

Is there a better explanation for Noah’s unexpected behavior?86 Yes. According to a statement attributed to Joseph Smith, Noah “was not drunk, but in a vision.”87 This agrees with the Genesis Apocryphon which, immediately after describing a ritual drinking of wine by Noah and his family, tells of a divine dream vision that revealed the fate of Noah’s posterity.88 Koler and Greenspahn89 concur that Noah was enwrapped in a vision while in the tent, commenting that “this explains why Shem and [Japheth] refrained from looking at Noah even after they had covered him, significantly ‘ahorannît [= Hebrew “backward”] occurs elsewhere with regard to avoidance of looking directly at God in the course of revelation.”

Noah’s fitness to enjoy the presence of God is explored in detail by Morales.90 “In every sense,” he writes, “Noah is defined as the one able ‘to enter’”91 into the presence of the Lord. He concludes:92

As the righteous man, Noah not only passes through the [door] of the Ark sanctuary,93 but is able to approach the mount of Yahweh for worship…. Noah stands as a new Adam, the primordial man who dwells in the divine Presence … As such, he foreshadows the high priest of the Tabernacle cultus who alone will enter the paradisiacal holy of holies….

[Page 101]How does wine play into the picture? It should be remembered that a sacramental libation was an element in the highest ordinances of the priesthood as much in ancient times as it is today. For example, only five chapters after the end of the Flood story, we read that Melchizedek “brought forth bread and wine”94 to Abraham as part of the ordinance that was to make him a king and a priest after Melchizedek’s holy order.95 Just as Melchizedek then blessed the “most high God, which had delivered thine enemies into thine hand,”96 so Noah, according to the Genesis Apocryphon, partook of the wine with his family and blessed “the God Most High, who had delivered us from the destruction.”97 The book of Jubilees further confirms that Noah’s drinking of the wine should be seen in a ritual context, not merely as a spontaneous indulgence that occurred at the end of a particularly wearying day. Indeed, we are specifically told that Noah “guarded” the wine until the time of the fifth New Year festival, the “first day on the first of the first month,” when he “made a feast with rejoicing. And he made a burnt offering to the Lord.”98

We find greater detail about an analogous event within the Testament of Levi. There we read that as Levi was being made a king and a priest, he was anointed, washed, and given “bread and holy wine” prior to his being arrayed in a “holy and glorious vestment.” Note also that the themes of anointing, the removal of outer clothing, the washing of the feet, and the ritual partaking of bread and wine were prominent in the events surrounding the Last Supper of Jesus Christ with the Apostles. Indeed, we are told that the righteous may joyfully anticipate participation in a similar event when the Lord returns: “for the hour cometh that I will drink of the fruit of the vine with you on the earth.”99

How do we make sense of Noah’s being “uncovered” during his vision? Perhaps the closest Old Testament parallel to this practice is when Saul, like the prophets who were with him, “stripped off his clothes … and prophesied before Samuel … and lay down naked all that day and all that night.”100 Jamieson101 clarifies that “lay down naked” in this instance meant only that he was “divested of his armor and outer robes.” In a similar sense, when we read in John 21:7 that Peter “was naked” as he was fishing, it simply meant that “he had laid off his outer garment, and had on only his inner garment or tunic.”102

How do we understand the statement that Ham “saw the nakedness of his father”? Reluctant to attribute the apparent gravity of Ham’s misdeed to the mere act of seeing, readers have often concluded that Ham in addition must have done something.103 For example, a popular proposal [Page 102]is that Ham committed unspeakable crimes against his mother104 or his father.105

Wenham, however, wisely observes that “these and other suggestions are disproved by the next verse” that recounts how Shem and Japheth covered their father: 106

As Cassuto107 points out: “If the covering was an adequate remedy, it follows that the misdemeanor was confined to seeing.” The elaborate efforts Shem and Japheth made to avoid looking at their father demonstrate that this was all Ham did in the tent.108

All this is consistent with the proposal that the misdeed of Ham was intrusively entering the tent of Yahweh and seeing Noah in the presence of God while the latter was “in the course of revelation.”109 While Noah, the righteous and blameless — an exception to those in his generation110 — was in a position to speak with God face-to-face, Ham was neither qualified nor authorized to see, let alone enter into, a place of divine glory.

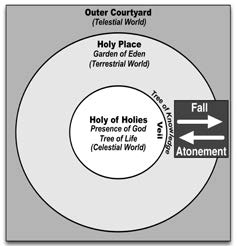

Figure 1. Zones of Sacredness in Eden and in the Temple (adapted from G. A. Anderson, Perfection, p. 80).114

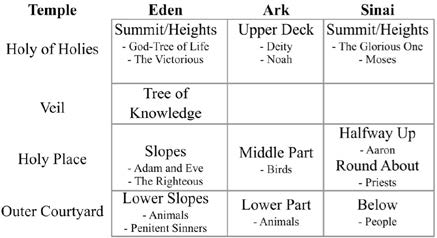

In describing his concept of Eden, Ephrem cited parallels with the division of the animals [Page 103]on Noah’s ark and the demarcations on Sinai separating Moses, Aaron, the priests, and the people, as shown in Figure 2. Ephrem pictured Paradise as a great mountain, with the tree of knowledge providing a boundary partway up the slopes. The tree of knowledge, Ephrem concluded, “acts as a sanctuary curtain [i.e., veil] hiding the Holy of Holies which is the Tree of Life higher up.”

Figure 2. Ephrem the Syrian’s Conception of Eden, the Ark, and Sinai

(adapted from Brock in Ephrem the Syrian, Paradise, p. 53).115

Recurring throughout the Old Testament are echoes of such a layout of sacred spaces and the accounts of dire consequences for those who attempt unauthorized entry through the veil into the innermost sanctuary. By way of analogy to the situation of Adam and Eve and its setting in the temple-like layout of the Garden of Eden, service in Israelite temples under conditions of worthiness was intended to sanctify the participants. However, as taught in Levitical laws of purity, doing the same “while defiled by sin, was to court unnecessary danger, perhaps even death.”116

If this understanding of the situation in Eden is correct, the sin of Ham would be a striking parallel to the transgression of Adam and Eve.117 Noah was positioned directly in front of, or perhaps even seated on, a representation of the throne of God.118 Without proper invitation, Ham approached the curtains of the “tent of Yaweh”119 and looked at the glory of God that was “uncovered within”120 — literally, “in the midst of”121 — the tent, just as Eve “cleared a path” for herself so she could “come close to the Tree of Life”122 that was located “in the midst of”123 the Garden. Emerging from the tent, Noah cursed Canaan,124 who is likened [Page 104]in the Zohar to the “primordial serpent”125 that was cursed by God in Eden.

By way of contrast to Ham and Canaan, Targum Neofiti asserts that the specific blessing given by Noah to his birthright son Shem is to have the immediate presence of the Lord with him and with his posterity:126 “[M]ay the Glory of his Shekhinah dwell in the midst of the tents of Shem.”

What is meant by the “nakedness” of Noah? As with Noah’s drinking of the wine, some readers see his “nakedness” as shameful. However, as an alternative, what has just been outlined about Ham’s having intrusively looked at the divine Presence within the sanctuary might be sufficient explanation for the description.

Going further, however, Nibley127 argued from the interpretations of some ancient readers128 that the Hebrew term for “nakedness” in this verse, ‘erwat, might be better rendered as “skins,” or ‘orot — in other words, an animal skin garment corresponding, in this instance, to the “coats of skins”129 [kuttonet ‘or] given to Adam and Eve for their protection after the Fall. The two Hebrew words ‘erwat and ‘orot would have looked nearly identical in their original unpointed form. Midrash Rabbah specifically asserts that the garment of Adam had been handed down to Noah, who wore it when he offered sacrifice.130

In the current context, the possibility signaled by Morales131 that “the ‘covering [mikseh] of the Ark’132 establishes a link to the [skin] ‘covering of the Tabernacle’”133 is significant.134 The idea that not only the Ark and the Tabernacle but also Noah himself might have been covered in a priestly garment of skins is intriguing when we consider Philonenko’s observation that “the temple is [itself] considered as a person and the veil of the temple as a garment that is worn, as a personification of the sanctuary itself.”135 Could it be that just as it is specifically pointed out in scripture that Noah “removed the [skin] covering of the Ark” in Genesis 8:13, he subsequently removed his own ritual covering of skins? This “garment of repentance”136 — which, by the way, was worn in those times as outer rather than inner clothing — was taken off by Noah in preparation for his being “clothed upon with glory.”137

The tradition of the stolen garment. Some ancient readers went further, stating that Ham not only saw but also took the “skin garment” of his father, intending to usurp his priesthood authority. In one of the earliest extant sources for this idea, Rabbi Judah said, “The tunic that the Holy One, blessed be His Name, made for Adam and his wife was with Noah [Page 105]in the Ark; when they left the Ark, Ham, the son of Noah, took it, and left with it, then passed it on to Nimrod.”138

Rabbi Eliezer, among others, continues the intrigues of the stolen garment forward to the time of Esau, who murdered Nimrod for it, and to Jacob, who had been enjoined by Rebekah to wear it, as she supposed, in order to obtain Isaac’s blessing.139 In turn, Nibley traces the theme backward to traditions telling of how Satan conspired to get the garment from Adam and Eve140 and to accounts of the premortal fight in heaven for the possession of the garment of light.141

Summary and Conclusions

The story of Noah not only repeats the stories of the Creation,142 the Garden,143 and the Fall of Adam and Eve144 but also replays the temple themes in those accounts. These themes are especially apparent in the stories of the Ark and the tent, both of which foreshadowed the later tabernacle of Moses.

While unequivocal confirming evidence in reliable ancient sources of certain details in the account of Noah is likely to remain elusive, unmistakable allusions throughout the stories in Genesis and in other Flood accounts from the ancient Near East make clear that we must regard them as temple texts that have been written at a high degree of sophistication. Without modern revelation, we might have continued “all at sea” in our understanding of Ark and the tent. However, with the additional light of the revelations and teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, we are on solid ground.

This article adapts and abridges material previously published in:

- Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and David J. Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014;

- Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary.” In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), pp. 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

[Page 106]References

Abarqu’s cypress tree: After 4000 years still gracefully standing. 2008. In CAIS News, The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies. http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2008/April2008/25-04.htm. (accessed August 1, 2012).

al-Tha’labi, Abu Ishaq Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim. d. 1035. ’Ara’is Al-Majalis Fi Qisas Al-Anbiya’ or “Lives of the Prophets.” Translated by William M. Brinner. Studies in Arabic Literature, Supplements to the Journal of Arabic Literature, Volume 24, ed. Suzanne Pinckney Stetkevych. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Allberry, Charles Robert Cecil Augustine, ed. A Manichaean Psalm-Book, Part 2. Manichaean Manuscripts in the Chester Beatty Collection 2. Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer, 1938.

Alter, Robert, ed. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2004.

— — — , ed. The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2007.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Anderson, Gary A., and Michael Stone, eds. A Synopsis of the Books of Adam and Eve. 2nd ed. Society of Biblical Literature: Early Judaism and its Literature, ed. John C. Reeves. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1999.

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Augustine. d. 430. St. Augustine: The Literal Meaning of Genesis. New ed. Ancient Christian Writers, 41 and 42. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1982.

Barker, Kenneth L., ed. Zondervan NIV Study Bible Fully Revised ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

Barker, Margaret. “Atonement: The rite of healing.” Scottish Journal of Theology 49, no. 1 (1996): 1-20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/scottish-journal-of-theology/article/abs/atonement-the-rite-of-healing/ECB25D3391C9D1026FD6E00C5EB36270. (accessed August 3).

— — — . E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, June 11, 2007.

[Page 107]— — — . The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

Beale, Gregory K. The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. New Studies in Biblical Theology, 1, ed. Donald A. Carson. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004.

Bergsma, John Sietze, and Scott Walker Hahn. “Noah’s nakedness and the curse on Canaan (Genesis 9:20-27).” Journal of Biblical Literature 124, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 25-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30040989. (accessed June 5, 2012).

bin Gorion (Berdichevsky), Micha Joseph. 1919. Die Sagen der Juden. Köln, Germany: Parkland Verlag, 1997.

bin Gorion, Micha Joseph (Berdichevsky), and Emanuel bin Gorion, eds. 1939-1945. Mimekor Yisrael: Classical Jewish Folktales. 3 vols. Translated by I. M. Lask. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Black, Jeremy A., G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zolyomi. “Enki’s journey to Nibru.” In The Literature of Ancient Sumer, edited by Jeremy A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson and G. Zolyomi, 330-33. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

— — — , eds. The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. “The structure of P.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 38, no. 3 (1976): 275-92.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. 2010. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 update ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

— — — . 2010. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

— — — . 2012. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

— — — . “The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary.” In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), pp. 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. “Mormonism’s Satan and the Tree of Life (Longer version of an invited presentation originally [Page 108]given at the 2009 Conference of the European Mormon Studies Association, Turin, Italy, 30-31 July 2009).” Element: A Journal of Mormon Philosophy and Theology 4, no. 2 (2010): 1-54.

— — — . “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42.

Brodie, Thomas L. Genesis as Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Pres, 2001.

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Buck, Christopher. Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Baha’i Faith. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999.

Budge, E. A. Wallis, ed. The Book of the Cave of Treasures. London, England: The Religious Tract Society, 1927. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Butterworth, Edric Allen Schofeld. The Tree at the Navel of the Earth. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, 1970.

Carter, R. A. “Watercraft.” In A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, edited by Daniel T. Potts. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World, 347-72. New York City, NY: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. http://books.google.com/books?id=7lK6l7oF_ccC. (accessed 24 July 2012).

Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 1: From Adam to Noah. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998.

— — — . 1949. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 2: From Noah to Abraham. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1997.

Chouraqui, André, ed. La Bible. Paris, France: Desclée de Brouwer, 2003.

Clifford, Richard J. The Cosmic Mountain in Canaan and the Old Testament. Harvard Semitic Monographs 4, ed. Frank Moore Cross, William L. Moran, Isadore Twersky and G. Ernest Wright. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, n.d.

— — — . “The temple and the holy mountain.” In The Temple in Antiquity, edited by Truman G. Madsen, pp. 107-24. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1984.

[Page 109]Cohen, Chayim. “Hebrew tbh: Proposed etymologies.” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 4 (1972): 37-51. http://www.jtsa.edu/Documents/pagedocs/JANES/1972%24/CCohen4.pdf. (accessed May 20, 2012).

Cohen, H. Hirsch. The Drunkenness of Noah. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1974.

Dalley, Stephanie. “Atrahasis.” In Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, edited by Stephanie Dalley. Oxford World’s Classics, pp. 1-38. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2000.

De Vaux, Roland, ed. La Bible de Jérusalem Nouvelle ed. Paris, France: Desclée de Brouwer, 1975.

Dogniez, Cécile, and Marguerite Harl, eds. Le Pentateuque d’Alexandrie: Texte Grec et Traduction. La Bible des Septante, ed. Cécile Dogniez and Marguerite Harl. Paris, France: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2001.

Douglas, Mary. “Atonement in Leviticus.” Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1993-1994): 109-30.

— — — . Leviticus as Literature. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Drower, E. S., ed. The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1959. http://www.gnosis.org/library/ginzarba.htm. (accessed September 11, 2012).

Dunn, James D. G., and John W. Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Eden, Giulio Busi. “The mystical architecture of Eden in the Jewish tradition.” In The Earthly Paradise: The Garden of Eden from Antiquity to Modernity, edited by F. Regina Psaki and Charles Hindley. International Studies in Formative Christianity and Judaism, 15-22. Binghamton, NY: Academic Studies in the History of Judaism, Global Publications, State University of New York at Binghamton, 2002.

Embry, Brad. “The ‘naked narrative’ from Noah to Leviticus: Reassessing voyeurism in the account of Noah’s nakedness in Genesis 9:22-24.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 35, no. 4 (2011): 417-33.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. Hymns on Paradise. Translated by Sebastian Brock. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

— — — . ca. 350-363. “The Hymns on Paradise.” In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

[Page 110]Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Feliks, Jehuda. “Cypress.” In Encyclopedia Judaica, edited by Fred Skolnik. Second ed. 22 vols. New York City, NY: Macmillan Reference, 2007. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0005_0_04781.html. (accessed August 1, 2012).

Fisk, Bruce N. Do You Not Remember? Scripture, Story, and Exegesis in the Rewritten Bible of Pseudo-Philo. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Fitzmyer, Joseph A., ed. The Genesis Apocryphon of Qumran Cave 1 (1Q20): A Commentary Third ed. Biblica et Orientalia 18/B. Rome, Italy: Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2004.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah. 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

George, Andrew, ed. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London, England: The Penguin Group, 2003.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Harper, Elizabeth A. 2011. You shall make a tebah. First draft paper prepared as part of initial research into a doctorate on the Flood Narrative. In Elizabeth Harper’s Web Site. http://www.eharper.nildram.co.uk/pdf/makeark.pdf. (accessed June 18, 2012).

Haynes, Stephen R. Noah’s Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Hennecke, Edgar, and Wilhelm Schneemelcher. “The Acts of Thomas.” In New Testament Apocrypha, edited by Edgar Hennecke and Wilhelm Schneemelcher. 2 vols. Vol. 2, 425-531. Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1965.

Hodges, Horace Jeffery. “Milton’s muse as brooding dove: Unstable image on a chaos of sources.” Milton Studies of Korea 12, no. 2 (2002): 365-92. http://memes.or.kr/sources/%C7%D0%C8%B8%C1%F6/%B9%D0%C5%CF%BF%AC%B1%B8/12-2/11.Hodges.pdf. [Page 111](accessed August 25).

Holloway, Steven Winford. “What ship goes there: The flood narratives in the Gilgamesh Epic and Genesis considered in light of ancient Near Eastern temple ideology.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 103, no. 3 (1991): 328-55.

Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel, and David Rolph Seely. My Father’s House: Temple Worship and Symbolism in the New Testament. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1994.

Jackson, Abraham Valentine Williams. “The cypress of Kashmar and Zoroaster.” In Zoroastrian Studies: The Iranian Religion and Various Monographs, edited by Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson, 255-66. New York City, NY: Columbia Press, 1928. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Zarathushtrian/cypress_zoroaster.htm. (accessed August 1, 2012).

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005.

Jacobsen, Thorkild. “The Eridu Genesis.” In The Harps That Once … Sumerian Poetry in Translation, edited by Thorkild Jacobsen. Translated by Thorkild Jacobsen, pp. 145-50. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

Jamieson, Robert, Andrew Robert Fausset, and David Brown. 1871. A Commentary Critical and Explanatory on the Whole Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1967.

Kaplan, Arye, ed. La Torah Vivante: Les Cinq Livres de Moïse. Translated by Nehama Kohn. New York City, NY: Moznaim, 1996.

Kee, Howard C. “Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, pp. 775-828. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Kugel, James L. Traditions of the Bible. Revised ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Lidzbarski, Mark, ed. Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer. 2 vols. Giessen, Germany: Alfred Töpelmann, 1905, 1915.

— — — , ed. Ginza: Der Schatz oder das Grosse Buch der Mandäer. Quellen der Religionsgeschichte, der Reihenfolge des Erscheinens 13:4. Göttingen and Leipzig, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, J. C. Hinrichs’sche, 1925.

Lundquist, John M. “What is reality?” In By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist [Page 112]and Stephen D. Ricks. 2 vols. Vol. 1, pp. 428-38. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990.

— — — . The Temple: Meeting Place of Heaven and Earth. London, England: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Malan, Solomon Caesar, ed. The Book of Adam and Eve: Also Called The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan: A Book of the Early Eastern Church. Translated from the Ethiopic, with Notes from the Kufale, Talmud, Midrashim, and Other Eastern Works. London, England: Williams and Norgate, 1882. Reprint, San Diego, CA: The Book Tree, 2005.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. “Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen ar).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, pp. 230-37. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

Matt, Daniel C., ed. The Zohar, Pritzker Edition. Vol. 1. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

— — — , ed. The Zohar, Pritzker Edition. Vol. 2. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

McCann, Jason Michael. “’Woven-of-Reeds’: Genesis 6:14b as evidence for the preservation of the reed-hut Urheiligtum in the biblical flood narrative.” In Opening Heaven’s Floodgates: The Genesis Flood Narrative, Its Context and Reception, edited by Jason M. Silverman. Bible Intersections 12, pp. 113-39. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2013.

McConkie, Joseph Fielding, and Craig J. Ostler, eds. Revelations of the Restoration: A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants and Other Modern Revelations. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000.

McNamara, Martin, ed. Targum Neofiti 1, Genesis, translated, with apparatus and notes. Vol. 1a. Aramaic Bible. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992.

Mead, George Robert Shaw, ed. 1921. Pistis Sophia: The Gnostic Tradition of Mary Magdalene, Jesus, and His Disciples (Askew Codex). Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2005.

Milton, John. 1667. “Paradise Lost.” In Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, Samson Agonistes, edited by Harold Bloom, pp. 15-257. London, England: Collier, 1962.

Morales, L. Michael. The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus. Biblical Tools and Studies 15, ed. B. Doyle, G. Van Belle, J. Verheyden and K. U. Leuven. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2012.

[Page 113]Morray-Jones, Christopher R. A. “Transformational mysticism in the apocalyptic-merkabah tradition.” Journal of Jewish Studies 43 (1992): 1-31.

— — — . “Divine names, celestial sanctuaries, and visionary ascents: Approaching the New Testament from the perspective of Merkava traditions.” In The Mystery of God: Early Jewish Mysticism and the New Testament, edited by Christopher Rowland and Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 12, eds. Pieter Willem van der Horst and Peter J. Tomson, pp. 219-498. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Morrow, Jeff. “Creation as temple-building and work as liturgy in Genesis 1-3.” Journal of the Orthodox Center for the Advancement of Biblical Studies (JOCABS) 2, no. 1 (2009). http://www.ocabs.org/journal/index.php/jocabs/article/viewFile/43/18 (accessed July 2, 2009).

Neusner, Jacob, ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 1: Parashiyyot One through Thirty-Three on Genesis 1:1 to 8:14. Brown Judaic Studies 104, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

— — — , ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 2: Parashiyyot Thirty-Four through Sixty-Seven on Genesis 8:15-28:9. Brown Judaic Studies 105, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. “The Babylonian Background.” In Lehi in the Desert, The World of the Jaredites, There Were Jaredites, edited by John W. Welch, Darrell L. Matthews and Stephen R. Callister. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 5, pp. 350-79. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

— — — . “A twilight world.” In Lehi in the Desert, The World of the Jaredites, There Were Jaredites, edited by John W. Welch, Darrell L. Matthews, and Stephen R. Callister. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 5, 153-71. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

— — — . 1966. “Tenting, toll, and taxing.” In The Ancient State, edited by Donald W. Perry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, pp. 33-98. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991.

— — — . 1967. “Apocryphal writings and the teachings of the Dead Sea Scrolls.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. [Page 114]The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, pp. 264-335. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992.

— — — . 1973. “Treasures in the heavens.” In Old Testament and Related Studies, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 1, 171-214. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

— — — . 1975. “Sacred vestments.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 91-138. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992.

— — — . 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

— — — . 1980. “Before Adam.” In Old Testament and Related Studies, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 1, 49-85. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

— — — . 1986. “Return to the temple.” In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 42-90. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

Noah, Mordecai M., ed. 1840. The Book of Jasher. Translated by Moses Samuel. Salt Lake City, UT: Joseph Hyrum Parry, 1887. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Oppenheim, A. Leo. 1961. “II. The Mesopotamian temple.” In The Biblical Archaeologist Reader, edited by G. Ernest Wright and David Noel Freedman. 2 vols. Vol. 1, pp. 158-69. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1975.

Origen. ca. 200-254. “Commentary on John.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers (The Writings of the Fathers Down to ad 325), edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. 10 vols. Vol. 10, pp. 297-408. Buffalo, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1896. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Ostler, Blake T. “Clothed upon: A unique aspect of Christian antiquity.” BYU Studies 22, no. 1 (1981): 1-15.

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Éric Smilévitch, eds. 1983. Chapitres de Rabbi Éliézer (Pirqé de Rabbi Éliézer): Midrach sur Genèse, Exode, Nombres, Esther. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1992.

Parry, Donald W. “Garden of Eden: Prototype sanctuary.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, pp. 126-51. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

— — — . “The cherubim, the flaming sword, the path, and the tree of life.” In The Tree of Life: From Eden to Eternity, edited by John W. Welch and Donald W. Parry, pp. 1-24. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011.

[Page 115]Parry, Jay A., and Donald W. Parry. “The temple in heaven: Its description and significance.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, pp. 515-32. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Potts, Daniel T. Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. http://books.google.com/books?id=OdZS9gBu4KwC. (accessed July 24, 2012).

Pseudo-Lucian. 1913. The Syrian Goddess: ‘De Dea Syria’, ed. Herbert A. Strong and John Garstang: Forgotten Books, 2007. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=as6QWT3ha3gC. (accessed August 8, 2012).

Pseudo-Philo. The Biblical Antiquities of Philo. Translated by Montague Rhodes James. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 1917. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006.

Rey, Alain. Dictionnaire Historique de la Langue Française. 2 vols. 3ième ed. Paris, France: Dictionnaires Le Robert, 2000.

Ri, Andreas Su-Min, ed. La Caverne des Trésors: Les deux recensions syriaques. 2 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 486-487 (Scriptores Syri 207-208). Louvain, Belgium: Peeters, 1987.

— — — . Commentaire de la Caverne des Trésors: Étude sur l’Histoire du Texte et de ses Sources. Vol. Supplementary. Volume 103. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 581. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2000.

Robinson, Edward. A Dictionary of the Holy Bible for General Use in the Study of the Scriptures with Engravings, Maps, and Tables. New York City, NY: The American Tract Society, 1859. http://books.google.com/books/about/A_Dictionary_of_the_Holy_Bible.html?id=fMgRAAAAYAAJ. (accessed July 28, 2012).

Robinson, Stephen E., and H. Dean Garrett, eds. A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants. 4 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2001-2005.

Sailhamer, John H. “Genesis.” In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelein, pp. 1-284. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Seixas, Joshua. A Manual of Hebrew Grammar for the Use of Beginners. Second enlarged and improved ed. Andover, MA: Gould and [Page 116]Newman, 1834. Reprint, Facsimile Edition. Salt Lake City, UT: Sunstone Foundation, 1981.

Smith, Mark S. The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010.

Sparks, Jack Norman, and Peter E. Gillquist, eds. The Orthodox Study Bible. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2008.

Steinmetz, Devora. “Vineyard, farm, and garden: The drunkenness of Noah in the context of primeval history.” Journal of Biblical Literature 113, no. 2 (1994): 193-207.

Stordalen, Terje. Echoes of Eden: Genesis 2-3 and the Symbolism of the Eden Garden in Biblical Hebrew Literature. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2000.

Tomasino, Anthony J. “History repeats itself: The “fall” and Noah’s drunkenness.” Vetus Testamentum 42, no. 1 (January 1992): 128-30.

Tsumura, David Toshio. The First Book of Samuel. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament, ed. Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2007.

Tvedtnes, John A. “Priestly clothing in Bible times.” In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, pp. 649-704. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Vogels, Walter. «Cham découvre les limites de son père Noé.» Nouvelle Revue Théologique 109, no. 4 (1987): 554-73.

Walker, Charles Lowell. Diary of Charles Lowell Walker. 2 vols, ed. A. Karl Larson and Katharine Miles Larson. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1980.

Walton, John H. Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2011.

Wenham, Gordon J., ed. Genesis 1-15. Word Biblical Commentary 1: Nelson Reference and Electronic, 1987.

— — — . “Sanctuary symbolism in the Garden of Eden story.” In I Studied Inscriptions Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, edited by Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura. Sources for Biblical and Theological Study 4, pp. 399-404. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

Westermann, Claus, ed. 1974. Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary 1st ed. Translated by John J. Scullion. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1994.

Wevers, John William. Notes on the Greek Text of Genesis. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993.

[Page 117]Wintermute, O. S. “Jubilees.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, pp. 35-142. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Wyatt, Nicolas. “‘Water, water everywhere … ’: Musings on the aqueous myths of the Near East.” In The Mythic Mind: Essays on Cosmology and Religion in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicholas Wyatt, 189-237. London, England: Equinox, 2005.

Zlotowitz, Rabbi Meir, and Rabbi Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

… that if each deck were further subdivided into three sections [cf. Gilgamesh’s nine sections (A. George, Gilgamesh, 11:62, p. 90)], the Ark would have had three decks the same height as the Tabernacle and three sections on each deck the same size as the Tabernacle courtyard. Regarding similarities in the Genesis 1 account of Creation, the Exodus 25ff. account of the building of the Tabernacle, and the account of the building of the ark, Sailhamer writes (J. H. Sailhamer, Genesis, p. 82, see also table on p. 84): Each account has a discernible pattern: God speaks (wayyo’mer/wayedabber), an action is commanded (imperative/jussive), and the command is carried out (wayya’as) according to [Page 118]God’s will (wayehi ken/kaaser siwwah ‘elohim). The key to these similarities lies in the observation that each narrative concludes with a divine blessing (wayebarek, Genesis 1:28, 9:1; Exodus 39:43) and, in the case of the Tabernacle and Noah’s ark, a divinely ordained covenant (Genesis 6:8; Exodus 34:27; in this regard it is of some importance that later biblical tradition also associated the events of Genesis 1-3 with the making of a divine covenant; cf. Hosea 6:7). Noah, like Moses, followed closely the commands of God and in so doing found salvation and blessing in his covenant.

The sentence “and the ark went on the face of the waters” (Genesis 8:18) is not suited to a boat, which is navigated by its mariners, but to something that floats on the surface of the waters and moves in accordance with the thrust of the water and wind. Similarly, the subsequent statement (Genesis 8:4) “the ark came to rest … upon the mountains of Ararat” implies an object that can rest upon the ground; this is easy for an ark to do, since its bottom is straight and horizontal, but not for a ship.

Atonement translates the Hebrew kpr, but the meaning of kpr in a ritual context is not known. Investigations have uncovered only what actions were used in the rites of atonement, not what that action was believed to effect. The possibilities for its meaning are “cover” or “smear” or “wipe,” but these reveal no more than the exact meaning of “breaking bread” reveals about the Christian Eucharist …. should like to quote here from an article by Mary Douglas published’ … in Jewish Studies Quarterly (M. Douglas, Atonement, p. 117. See also M. Douglas, Leviticus, p. 234: “Leviticus actually says less about the need to wash or purge than it says about ‘covering.’”):

[Page 120]Terms derived from cleansing, washing and purging have imported into biblical scholarship distractions which have occluded Leviticus’ own very specific and clear description of atonement. According to the illustrative cases from Leviticus, to atone means to cover or recover, cover again, to repair a hole, cure a sickness, mend a rift, make good a torn or broken covering. As a noun, what is translated atonement, expiation or purgation means integument made good; conversely, the examples in the book indicate that defilement means integument torn. Atonement does not mean covering a sin so as to hide it from the sight of God; it means making good an outer layer which has rotted or been pierced.

This sounds very like the cosmic covenant with its system of bonds maintaining the created order, broken by sin and repaired by “atonement.”

These boats are … best understood as composite wooden-framed vessels with reed-bundle hulls. Such a boat would have been cheaper to build than one with a fully planked hull and stronger than one without a wooden frame … The use of wooden frames with reed-bundle hulls conforms to the archaeological evidence …

Both wooden and composite boats were covered with bitumen. The RJ-2 slabs also suggest that matting was stitched onto the reed hull prior to coating.

See also D. T. Potts, Mesopotamian Civilization, pp. 122-137.

… primary temple was … at Eridug deep in the marshes in the far south of Mesopotamia. Eridug was considered to be the oldest city, the first to be inhabited before the Flood … Excavations at Eridug have confirmed that ancient belief — and a small temple with burned offerings and fish bones was found [Page 121]in the lowest levels, dating to some time in the early fifth millennium bce.”

Eridug or Eridu, now Tell abu Shahrain in southern Mesopotamia, is associated by some scholars (e.g., N. M. Sarna, Genesis, p. 36) with the name of the biblical character “Irad” (Genesis 4:18), and the city built by his father Enoch, son of Cain (Genesis 4:17).

The carpenter [brought his axe,]

The reed worker [brought his stone,]

[A child brought] bitumen.

A. George, Gilgamesh, 11:53-55, p. 90:

The young men were … ,

the old men bearing ropes of palm-fibre

the rich man was carrying the pitch

The most wonderful thing about Jerusalem the Holy City is its mobility: at one time it is taken up to heaven and at another it descends to earth or even makes a rendezvous with the [Page 122]earthly Jerusalem at some point in space halfway between. In this respect both the city and the temple are best thought of in terms of a tent, … at least until the time comes when the saints “will no longer have to use a movable tent” [Origen, John, 10:23, p. 404. “The pitching of the tent outside the camp represents God’s remoteness from the impure world” (H. W. Nibley, Tenting, p. 79 n. 40)] according to the early Fathers, who get the idea from the New Testament … [e.g., “John 1:14 reads literally, ‘the logos was made flesh and pitched his tent [eskenosen] among us’; and after the Resurrection the Lord ‘camps’ with his disciples, Acts 1:4. At the Transfiguration Peter prematurely proposed setting up three tents for taking possession (Matthew 17:4; Mark 9:5; Luke 9:33)” (ibid., p. 80 n. 41)] It is now fairly certain, moreover, that the great temples of the ancients were not designed to be dwelling-houses of deity but rather stations or landing-places, fitted with inclined ramps, stairways, passageways, waiting-rooms, elaborate systems of gates, and so forth, for the convenience of traveling divinities, whose sacred boats and wagons stood ever ready to take them on their endless junkets from shrine to shrine and from festival to festival through the cosmic spaces. The Great Pyramid itself, we are now assured, is the symbol not of immovable stability but of constant migration and movement between the worlds; and the ziggurats of Mesopotamia, far from being immovable, are reproduced in the seven-stepped throne of the thundering sky-wagon.

[T]hou from the first

Wast present, and with mighty wings outspread

Dovelike satst brooding on the vast abyss

And mad’st it pregnant.”

“Brooding” enjoys rich connotations, including, as Nibley observes (H. W. Nibley, Before Adam, p. 69), not only “to sit or incubate [eggs] for the purpose of hatching” but also: … “to dwell continuously on a subject.” Brooding is just the right word — a quite long quiet period of preparation in which apparently nothing was happening. Something was to come out of the water, incubating, waiting — a long, long time. Some commentators emphatically deny any connection of the Hebrew term with the concept of brooding (e.g., U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, pp. 24-25). However, the “brooding” interpretation is not [Page 125]only attested by a Syriac cognate (F. Brown et al., Lexicon, 7363, p. 934b) but also has a venerable history, going back at least to Rashi, who spoke specifically of the relationship between the dove and its nest. In doing so, he referred to the Old French term acoveter, related both to the modern French couver (from Latin cubare — to brood and protect) and couvrir (from Latin cooperire — to cover completely). Intriguingly, this latter sense is related to the Hebrew term for the atonement, kipper (M. Barker, Atonement; A. Rey, Dictionnaire, 1:555). Going further, Barker admits the possibility of a subtle wordplay in examining the reversal of consonantal sounds between “brood/hover” and “atone”: “The verb for ‘hover’ is rchp, the middle letter is cheth, and the verb for ‘atone’ is kpr, the initial letter being a kaph, which had a similar sound. The same three consonantal sounds could have been word play, rchp/kpr” (M. Barker, 11 June 2007). “There is sound play like this in the temple style” (ibid.; see M. Barker, Hidden, pp. 15-17). In this admittedly speculative interpretation, one might see an image of God, prior to the first day of Creation, figuratively “hovering/atoning” [rchp/kpr] over the singularity of the inchoate universe, just as the Ark smeared with pitch [kaphar] later moved over the face of the waters “when the waters cover[ed] over and atone[d] for the violence of the world” (E. A. Harper, You Shall Make, p. 4).

7 days of waiting for flood (7:4)

7 days of waiting for flood (7:10)

40 days of flood (7:17a)

150 days of water triumphing (7:24)

150 days of water waning (8:3)

40 days of waiting (8:6)

7 days of waiting (8:10)

7 days of waiting (8:12)

The description of God’s rescue of Noah foreshadows God’s deliverance of Israel in the Exodus. Just as later “God [Page 126]remembered his covenant” (Exodus 2:24) and sent “a strong east wind” to dry up the waters before his people (Exodus 14:21) so that they “went through … on dry ground” (Exodus 14:22), so also in the story of the Flood we read that “God remembered” those in the ark and sent a “wind” over the waters (Genesis 8:1) so that his people might come out on “dry ground” (Genesis 8:14).

So striking is the contrast between Noah the saint who survived the Flood and Noah the inebriated vintner that many commentators argue that the two traditions are completely incompatible and must be of independent origin.

Given the analogy between the Garden [of Eden] and the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle/temple, and that between the Ark and the Tabernacle/temple, Noah’s entrance may be understood as that of a high priest … ascending the cosmic mountain of Yahweh — an idea “fleshed out,” as it were, when Noah walks the summit of the Ararat mount. The veil separating off the Holy of Holies served as an “objective and material witness to the conceptual boundary drawn between the area behind it and all other areas,” a manifest function of the Ark door.

When he saw his father’s nakedness, Ham went and told (wayyagged) his brothers about it (Genesis 9:22). When Adam and Eve told Yahweh God that they had hidden because they were naked, God asked, “Who told (higgid) you that you were naked?” (Genesis 3:1). The source of this information turned out to be the serpent. Furthermore, when Ham told his brothers about their father’s nudity, he was undoubtedly tempting them with forbidden knowledge (the opportunity to see their father’s nakedness). Finally, for his part in the Fall, the serpent was cursed (‘arur) more than any of the other creatures (Genesis 3:14). His offspring were doomed to be subject to the woman’s offspring (Genesis 3:15). Ham’s offspring, too, became cursed (‘arur), doomed to subjugation to the offspring of his brothers (Genesis 9:25).

Why the insistence on [the idea of being “clothed upon with glory”]? Enoch says, “I was clothed upon with glory. Therefore I could stand in the presence of God” (cf. Moses 1:2, 31). Otherwise he could not. It is the garment that gives confidence in the presence of God; one does not feel too exposed (2 Nephi 9:14). That garment is the garment … of divinity. So as Enoch says, “I was clothed upon with glory, and I saw the Lord” (Moses 7:3-4), just as Moses saw Him “face to face, … and the glory of God was upon Moses; therefore Moses could endure his presence (Moses 1:2). In 2 Enoch, discovered in 1892, we read, “The Lord spoke to me with his own mouth: … ‘Take Enoch and remove his earthly garments and anoint him with holy oil and clothe him in his garment of glory.’ … And I looked at myself, and I looked like one of the glorious ones” (see F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, 22:5, 8, 10, pp. 137, 139). Being no different from him in appearance, he is qualified now, in the manner of initiation. He can go back and join them because he has received a particular garment of glory.

It appears that the ritual garment of skins was needed only for a protection during one’s probation on earth. Ephrem the Syrian asserted that when Adam “returned to his former glory, … [he] no longer had any need of [fig] leaves or garments of skin” (Commentary on the Diatessaron, cited in M. Barker, Hidden, p. 34). Note also Joseph Smith’s careful description of the angel Moroni (JS-H 1:31): “I could discover that he had no other clothing on but this robe, as it was open, so that I could see into his bosom.” We infer that Moroni had forever laid aside his “garment of repentance,” since he was now permanently clothed with glory. The protection provided by the garment was accompanied by a promise of heavenly assistance. In this connection, Nibley paraphrases a passage from the Mandaean Ginza: “ … when Adam stood praying for light and knowledge a helper came to him, gave him a garment, and told him, ‘Those men who gave you the garment will assist you throughout your life until [Page 133]you are ready to leave earth’” (H. W. Nibley, Apocryphal, p. 299. The German reads: “Wie Adam dasteht und sich aufzuklären sucht, kam der Mann, sein Helfer. Der hohe Helfer kam zu ihm, der ihn in ein Stück reichen Glanzes hineintrug. Er sprach zu ihm: ‘Ziehe dein Gewand an … Die Männer, die dein Gewand geschaffen, dienen dir, bis du abscheidest’” (M. Lidzbarski, Ginza, GL 2:19, p. 488)).

When this time of probation ended, the garment of light or glory that was previously had in the heavenly realms was to be returned to the righteous. As Nibley explained (H. W. Nibley, Message 2005, p. 489). See also E. Hennecke et al., Acts of Thomas, 108.9-15, pp. 498-499; B. T. Ostler, Clothed, p. 4):

The garment [of light] represents the preexistent glory of the candidate … When he leaves on his earthly mission, it is laid up for him in heaven to await his return. It thus serves as security and lends urgency and weight to the need for following righteous ways on earth. For if one fails here, one loses not only one’s glorious future in the eternities to come, but also the whole accumulation of past deeds and accomplishments in the long ages of preexistence.

While Noah had not yet finished his probation when he spoke with Deity in the tent, he and others of the prophets experienced a temporary transfiguration that clothed them with glory and allowed them to endure God’s presence (see, e.g., Moses 1:12-14, 31; 7:3). A conjecture consistent with this view is that Ham took the garment of skins that Noah had laid temporarily aside during his transfiguration.

Abraham was stripped of his clothes and thrown into the fire naked, Gabriel brought him a shirt made from the silk of the Garden [of Eden] and clothed him in it. That shirt remained with Abraham, and when he died, Isaac inherited it. When Isaac died, Jacob inherited it from him, and when Joseph grew up, Jacob put that shirt in an amulet and placed it on Joseph’s neck to protect him from the evil eye. He never parted with it. When he was thrown into the pit naked, the angel came to him with the amulet. He took out the shirt, dressed Joseph in it, and kept him company by day.

Later, when Joseph learned that his aged father had lost his eyesight (ibid., p. 228):

… he gave them his shirt. Al-Dahhak said that that shirt was woven in Paradise, and it had the smell of Paradise. When it only touched an afflicted or ailing man, that man would be restored to health and be cured … [Joseph] said to them, “Take this shirt of mine and cast it on my father’s face, he will again be able to see” (Qur’an 12:93) …

Go here to see the 2 thoughts on ““The Ark and the Tent: Temple Symbolism in the Story of Noah”” or to comment on it.