Abstract: In this article, I discuss how the ancient analogue to what President Nelson has called “the covenant path” might be seen in the Book of Mormon and elsewhere in scripture not so much as a journey of covenant-keeping that takes us to the temple but as a journey that takes us through the temple. Throughout the Book of Mormon, observant readers will find not only the general outline of the doctrine of Christ but also corresponding details about the covenant path as represented in temple layout and furnishings. Nowhere is this truth better illustrated than in 2 Nephi 31:19–20 where Nephi summarizes the sequence of priesthood ordinances that prepare disciples to enter God’s presence. In doing so, he masterfully weaves in related imagery—guiding readers on an end-to-end tour of the temple while reminding them of the three cardinal virtues of faith, hope, and charity. The doctrinal richness of these two verses is a compelling demonstration of the value of President Nelson’s encouragement to study the biblical context of modern temples as a source of enlightenment about the meaning of the ordinances. This essay also suggests that the foundational elements of Latter-day Saint temple rites are ancient and were given to Joseph Smith very early in his ministry as he translated the Book of Mormon. It is hoped that a closer look at the beautiful imagery in 2 Nephi 31 will provide profitable reflection for readers.

From the time of his first public address to the Church after becoming president of the Church, Russell M. Nelson highlighted the importance of personal progression on the “covenant path.”1 Latter-day Saint temple symbolism reflects the idea that the nature of progress [Page 178]on the covenant path is incremental. It employs an invariable succession of covenants,2 names,3 relationships,4 roles,5 virtues,6 ordinances and priesthoods,7 and types of clothing8 as figurative signposts9 corresponding to different stages of existence and their associated glories. These signposts are accompanied by a series of tokens, signs, names, and key words. Symbolism of this sort is not modern in origin but was once employed in a range of religious settings throughout the ancient Near East and in early Christianity.10

President Nelson has also taught that temple worship is ancient. Going further he said that knowing that “temple rites are ancient . . . is thrilling and another evidence of their authenticity.” Temple worship is a “sacred and ageless work.”11

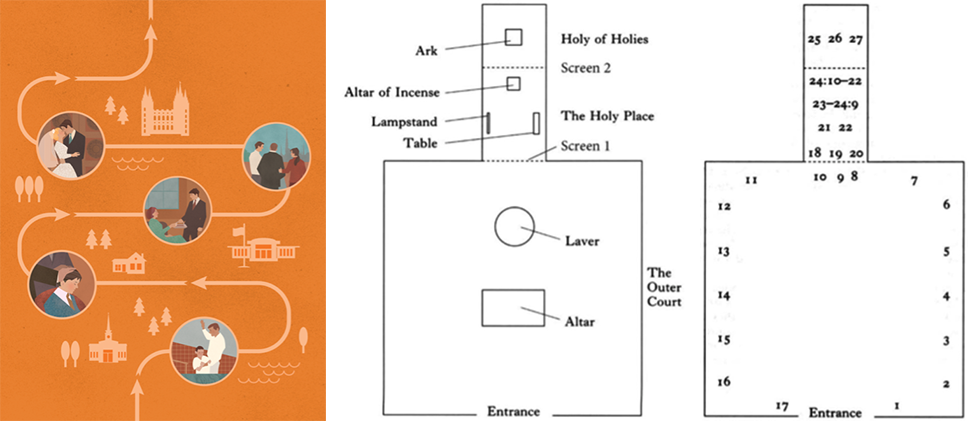

Figure 1 shows, at the left, an illustration of the covenant path from a Church magazine.12 It represents the path as a modern highway that passes through milestones representing priesthood ordinances. Such illustrations, conveying as they should the central role of ordinances in our progression toward eternal life, can be helpful teaching aids for modern readers. However, since the ordinances go back to the beginning of time, it may be useful to think about how the covenant path was envisioned anciently. The ancient analogue to the covenant path would not have been imagined as something that resembles a modern drive on a highway to the temple. Instead, what clues we possess indicate that it was often seen as a walking journey through the temple.

Figure 1. Left: Covenant path as a modern highway to the temple, passing through milestones representing required priesthood ordinances. Center and right: Mary Douglas’s correspondence of chapters in Leviticus to a counterclockwise movement through the temple.

For instance, John W. Welch has pointed attention to the research [Page 179]of Old Testament scholar Mary Douglas.13 In a brilliant leap of imagination, Douglas realized that the exposition of the laws contained in the book of Leviticus could be best understood when read as if they provided a tour through the ancient Israelite temple. The tour, illustrated in the center and right portions of figure 1, begins with a counterclockwise movement through the courtyard. Then it is followed by movement through the first veil into the Holy Place and then through the second veil into the Holy of Holies. Through this journey, temple worshippers who study Leviticus are exposed to the setting and context for the laws that were given to God’s people anciently. Thus, in this instance, the covenant path leads through the temple rather than to the temple.

One of the most important features of progress through the different spaces of sacredness in the endowment (whether represented as separate rooms or as different phases of existence within the same room) is that movement from one place to another is carefully controlled. The sequence of movement is always the same and is closely regulated by the temple workers, essentially “human cherubim,”14 who are assigned to lead temple worshipers in and out of each sacred space.

Following the example of Adam and Eve after the Fall, members of the endowment company are required to make covenants to keep the laws that apply to the next space they are preparing to enter before they are allowed to move there. For example, only those who have covenanted to keep the law of obedience and sacrifice are allowed to enter the space representing the mortal world, for those “who cannot abide the law of a telestial kingdom cannot abide a telestial glory” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:24). Likewise, only those who make a covenant to keep the law of the gospel while they are in the space representing the mortal world are allowed to enter the terrestrial world.

The principles of order that govern progress in the endowment are applicable to all ordinances, from baptism to the highest rites of the temple and beyond. Summarizing the progressive nature of the Nauvoo temple ordinances as they were introduced on 4 May 1842, Elder Willard Richards wrote that they included15

washings, anointings, endowments, and the communication of keys pertaining to the Aaronic Priesthood, and so on to the highest order of the Melchizedek Priesthood, setting forth the order pertaining to the Ancient of Days, and all those plans and principles by which anyone is enabled [Page 180]to secure the fulness of those blessings which have been prepared for the Church of the Firstborn, and come up and abide in the presence of the Elohim in the eternal worlds.

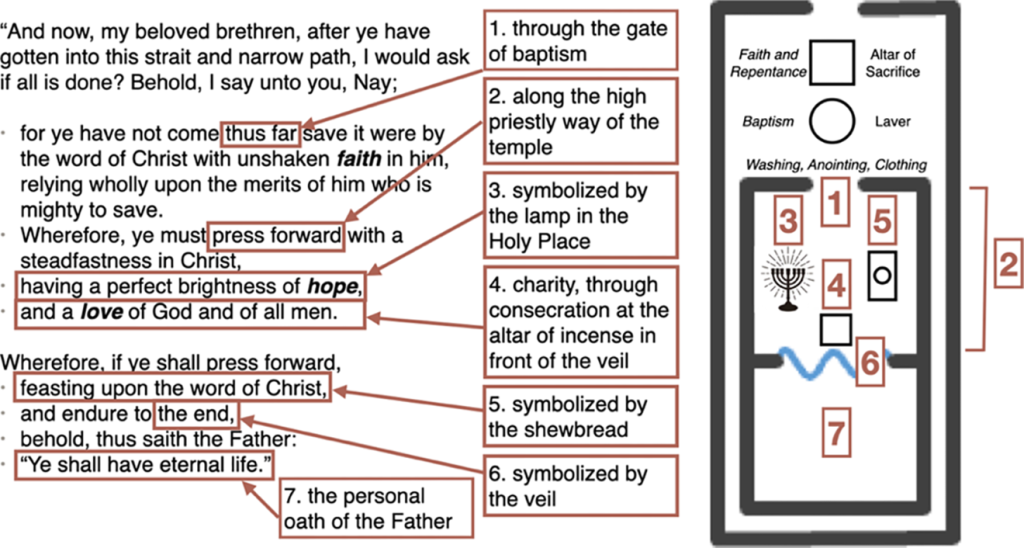

Faith, Hope, and Charity as the Principal Rungs on the Ladder of Exaltation

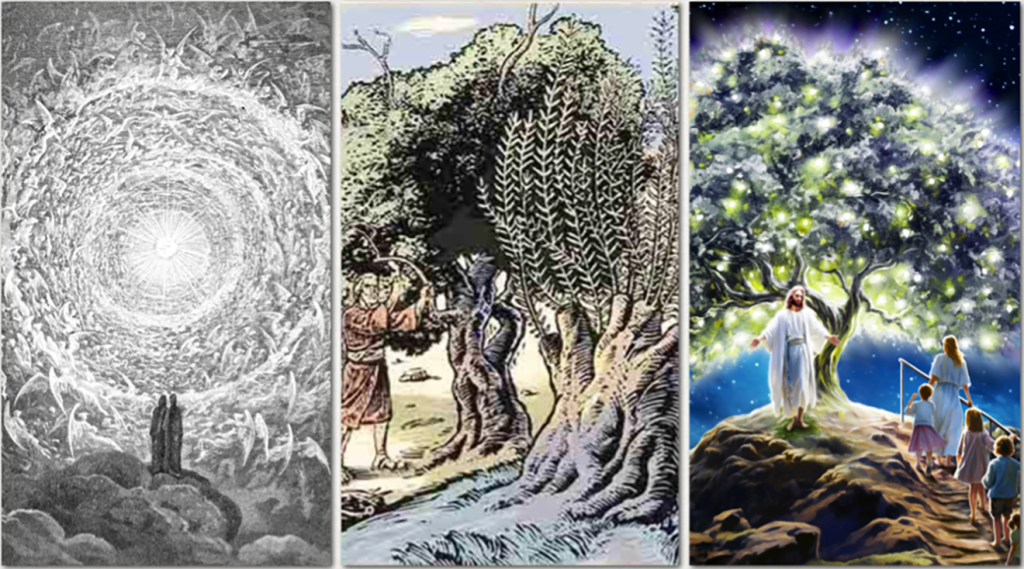

The orderly progression of Saints toward eternal life was often symbolized as a ladder of exaltation, drawn in part from the story of Jacob’s ladder in Genesis.16 Faith, hope, and charity—what eventually came to be known as the three theological virtues—were associated in the writings of early Christian teachers such as John Climacus, Saint Augustine, and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux with the three principal rungs on Jacob’s ladder. The ladder was a symbol of the general process of spiritual progression by which the disciple, enabled by the grace of God, climbs to perfection. Depictions such as the one in figure 2 also showed the fate of those who failed to hold firmly to the ladder as they continued their ascent. As in Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life, some, “after they had tasted of the fruit . . . fell away into forbidden paths and were lost” (1 Nephi 8:28).17

Figure 2. The Ladder of Virtues of St. John Climacus, north façade detail, Sucevita Monastery, Romania, 1602–1604. (Public domain.) The words above each rung of the ladder refer to Christian virtues. Angels hold a crown above the head of each ascending individual in anticipation of their being crowned as kings. The individual at the top of the ladder has already received his crown. The Lord greets him with a firm clasp of the wrist while displaying a parchment with writing in Old Slavonic that reads: “Come unto me all ye who labor and are heavy laden.”24

Table 1 illustrates how graphical depictions of the three principal rungs of the ladder in medieval times correspond to textual illustrations in the New Testament and in modern scripture. The table demonstrates that scriptural catalogs of virtues, far from being a randomly assembled laundry list, were usually deliberately structured to form an ordered progression leading to a culminating point.18 In Greek, Jewish, and Christian literature, this rhetorical device is called sorites, climax, or gradatio.19 Bible scholar Harold Attridge explained the incremental, ladder-like property of the personal qualities given in such lists:20

In this “ladder” of virtues, each virtue is the means of producing the next (this sense of the Greek is lost in translation). All the virtues grow out of faith, and all culminate in love.

Though some elements of the four lists differ,21 the qualities of faith, hope (or its equivalents, patience and endurance), and charity are always present, forming, as Joseph Neyrey puts it, “the determining framework in which other virtues are inserted.”22 The idea of three key virtues embedded within a varying list of secondary attributes appears to be very old. Although the biblical triad of faith, hope, and charity is, strictly speaking, a New Testament construct, older Old Testament analogues have also been proposed.23

[Page 181]In each of the instances shown in table 1, the promised reward is the same: personal fellowship with Deity—as also symbolized in the illustrations shown in figures 2, 10, and 11. Specifically, in Romans 5:2 disciples are told that they will “rejoice in hope of the glory of God.” This means they can look forward with glad confidence, knowing they “will be able to share in the revelation of God—in other words, that [they] will come to know Him as He is.”25

Similarly, in 2 Peter 1:4, 8, 10, disciples are promised that they will become “partakers of the divine nature” and that they will ultimately be fruitful “in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ”—thus, in Joseph Smith’s reading, making their “calling and election sure.”26 This is similar to the promise given in 2 Nephi 31:19–20, a passage we will discuss in more detail later below.

[Page 182]Table 1. Table illustrating how faith, hope, and charity—usually listed in this order—form the determining framework in which other personal qualities are inserted within longer lists of scriptural virtues.

| Romans 5:1–5 | 2 Peter 1:5–7 | 2 Nephi 31:19–20 | Doctrine and Covenants 4:6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| faith | faith | faith | faith |

| virtue | virtue | ||

| peace | knowledge | knowledge | |

| temperance | temperance | ||

| hope [patience27] | patience | hope | patience |

| godliness | |||

| brotherly kindness | brotherly kindness | ||

| godliness | |||

| love | charity | love | charity |

| humility | |||

| diligence |

Finally, the promise given to faithful Saints in Doctrine and Covenants 4:7 echoes the words of Jesus that outline requirements for entrance into the kingdom of heaven: “Ask, and it shall be given you. Seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you”28—a threefold promise that Matthew L. Bowen correlates to faith, hope, and charity.29

Note that, as discussed in more detail elsewhere,30 there are exactly ten virtues in the list and that, exceptionally, the last item is not charity.

2 Nephi 31–32 Traces the Covenant Path Through the Temple

Joseph Smith’s prophetic gifts enabled him to reveal things that were both old (that is, rooted in antiquity) and new (that is, newly revealed). As one of many examples of such revelations, we will now examine 2 Nephi 31–32, where Nephi provides “a few words . . . concerning the doctrine of Christ” (2 Nephi 31:2, 21; 32:6). 2 Nephi 31–32 is part of a set of significant scriptural passages in the New Testament and the Book of Mormon that describes the intimate relationship of the doctrine of Christ to the virtues of faith, hope, and charity (expressed, in this case, using the word love). These chapters and related passages are discussed in more detail elsewhere.31

In 2 Nephi 31–32, the relationship between the doctrine of Christ and faith, hope, and love is defined as a progression that successively [Page 183]highlights the different areas of the temple in which the ordinances and covenants relating to the three virtues are introduced:

- faith leads to justification through repentance, baptism, and the initial gift of the Holy Ghost in the temple courtyard

- hope and a capacity to “endure all things”32 increases through the enlightening influence of the Spirit until it leads to complete sanctification33 (“a fulness of the Holy Ghost,” Doctrine and Covenants 109:15), symbolized by, among other things, the illumination of the menorah in the Holy Place

- love qualifies the disciple for the presence of God in the Holy of Holies and, eventually, exaltation.

Note that faith, hope, and love are similarly highlighted in an exhortation to disciples to approach the temple veil in the book of Hebrews.34

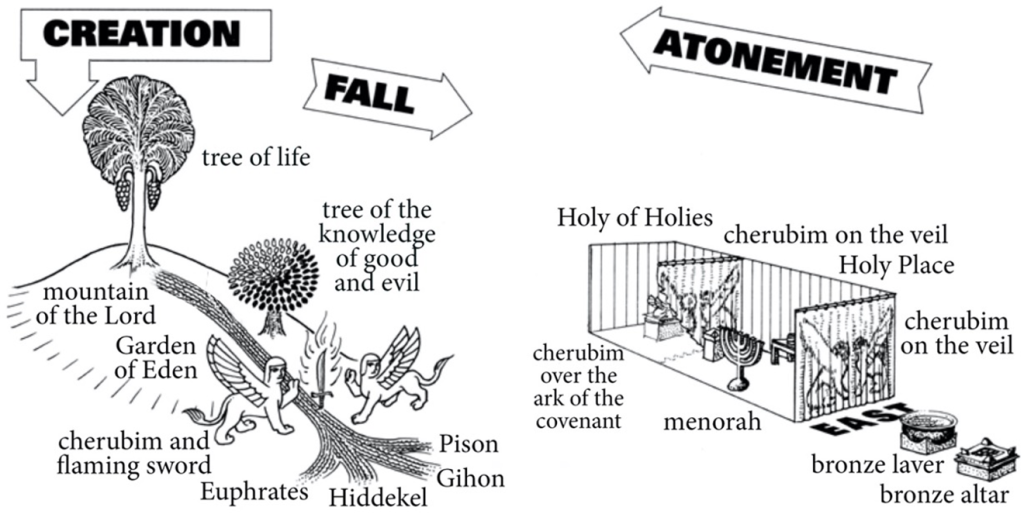

To fully grasp Nephi’s teachings, we need to understand that the course taken by the Israelite high priest through the temple symbolized the journey of the Fall of Adam and Eve in reverse (see figure 3). Specifically, as BYU professor Donald W. Parry has observed, just as the route of Adam and Eve’s departure from Eden led them eastward past the cherubim with the flaming swords and out of the sacred garden into the mortal world, so in ancient times the high priest would return westward, that is, from the mortal world, past the consuming fire, the cleansing water, the woven images of cherubim on the temple veils, and, finally, back into the presence of God.35 “Thus,” according to Parry, the Israelite high priest has returned “to the original point of creation, where he pours out the atoning blood of the sacrifice, reestablishing the covenant relationship with God.”36

Figure 3. Adapted from Michael P. Lyon, Sacred Topography of Eden and the Temple, 1994.40 The outbound journey of the Creation and the Fall at left is mirrored in the inbound journey of the temple at right. Each major feature of Eden (the river, the cherubim, the tree of knowledge,41 the tree of life) corresponds to a symbol in the Israelite temple (the bronze laver, the cherubim, the veil, the menorah). Likewise, the high priest is “cultic Adam.”42

The Two-Way Temple Journey Reflected in the Layout of Nephite and Modern Temples.37 Some Book of Mormon scholars believe that Nephite temple activities would have not only included the Aaronic priesthood ordinances of sacrifice just described, but also rites originally associated with Israelite royal priesthood “after the order of Melchizedek.”38 The Melchizedek priesthood rites seem to have differed in at least three respects.

1. Two-Way vs. One-Way Temple Journey. In line with Parry’s proposal that Israelite high priest’s westward journey of atonement represents a reversal of the Fall of Adam and Eve is evidence from elsewhere in antiquity that a story of creation and of the victory of the god over primordial adversaries (an analogue to the story of the Fall) were standard elements of temple ritual.39

[Page 184]Consistent with this idea, both Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saint scholars have proposed that the creation account of Genesis 1 may have been used within Israelite temple ceremonies.43 Going further, Louis Ginzberg has reconstructed ancient Jewish sources to argue that the results of each day of the Creation are symbolically reflected in temple furnishings.44 From this perspective, when God finished the Creation, what came of it was an earthly temple that was laid out and furnished in symbolic likeness to the heavenly temple. That earthly temple, the result of Creation, was none other than “Eden.” Its Holies of Holies was the celestial top of the figurative mountain of God, and its Holy Place was a Garden of terrestrial glory located on its “eastern” slope.

Carrying this idea forward to a later time, Exodus 40:33 describes how Moses completed the Tabernacle. The Hebrew text exactly parallels the account of how God finished creation (Moses 3:1).45 Genesis Rabbah comments on the significance of this parallel: “It is as if, on that day [on which the Tabernacle was raised in the wilderness], I actually created the world.”46 With this idea in mind, Hugh Nibley famously called the temple “a scale-model of the universe,”47 a place for taking bearings on the cosmos and finding one’s place within it.

The idea that the process of creation provides a model for subsequent temple building and ritual48 is found elsewhere in the ancient [Page 185]Near East. For example, this is made explicit in Nibley’s reading of the first, second, and sixth lines of the Babylonian creation story, Enuma Elish: “At once above when the heavens had not yet received their name and the earth below was not yet named. . . . The most inner sanctuary of the temple . . . had not yet been built.”49 Consistent with this reading, the account goes on to tell how the god Ea founded his sanctuary (1:77),50 after having “established his dwelling” (1:71, an analogue to the Creation account), “vanquished and trodden down his foes” (1:73, an analogue to God’s victory over the devilish serpent after the Fall of Adam and Eve51), and “rested” in his “sacred chamber” (1:75, an analogue to the Sabbath).

In the modern endowment—as also, it seems, in Nephite and early Christian equivalents of the temple ordinances—an explicit retelling of the Fall of Adam and Eve was the natural follow-on to the narrative of Creation. One purpose of relating the events of the Fall in modern temple ordinances is to make clear the absolute necessity of the later rites of atonement and investiture that are part of the bestowal of the fulness of the Melchizedek priesthood. However, even in the truncated Aaronic-priesthood version of the Israelite temple rites, the story of Adam and Eve seems to have implicitly informed the understanding of temple worshipers in ancient Israel.

For example, agreeing with Donald Parry’s proposal that Israelite temple rites were a reflection and reversal of the Fall, Leviticus scholar L. Michael Morales sees the Day of Atonement as an event that, for the children of Israel, “called upon both memory and faith: memory, a looking back to the first Adam’s failure and expulsion from divine Presence in Eden; faith, a looking forward to the remedy for that expulsion.”52

In summary, while the Old Testament description of the Day of Atonement depicts a one-way journey by priests into the temple, the (older) text of the Book of Mormon hints that the Melchizedek priesthood ordinances of the Nephites could have mirrored in a general way the two-way journey of modern temple worshipers.

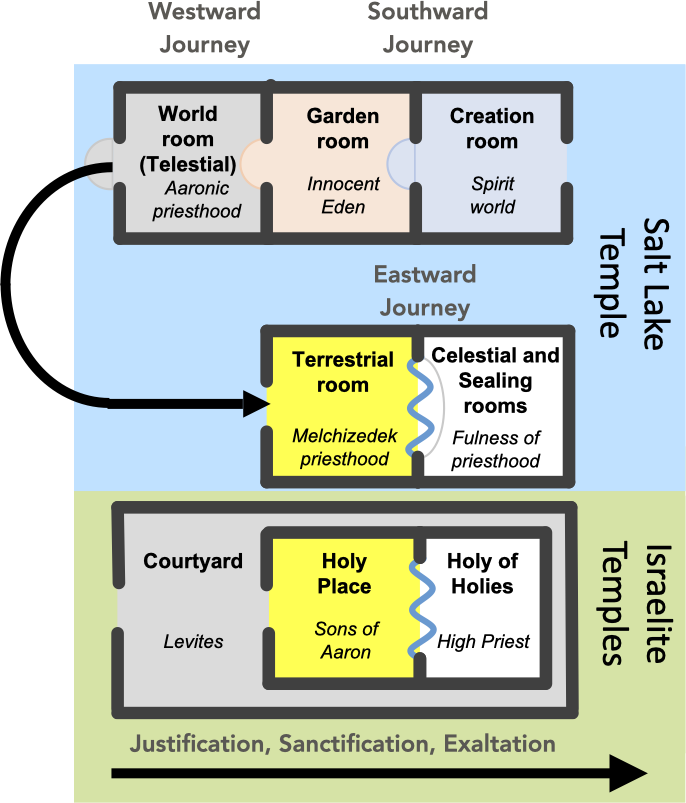

Figure 4 makes it clear how some early Latter-day Saint temples both reflected and adapted the overall layout of Israelite temples. In these temples, the rooms representing “celestial”53 (Holy of Holies), “terrestrial”54 (Holy Place), and “telestial” (baptismal) areas of sacredness of the endowment are doubled. This facilitates both the downward, “outward bound” journey of Adam and Eve from the Creation room to the Garden room to the World room (celestial to terrestrial to telestial) and their upward, “inward bound” return to the presence of [Page 186]God, starting with baptism and the Aaronic priesthood in the telestial or World room, and then progressing from the terrestrial to the celestial areas of the temple.

Figure 4. Layout of the Salt Lake Temple and Israelite temples.55

The two-way journey that involves turning away from the sinful world and back toward one’s heavenly origins is mirrored in the layout of ordinance rooms.56 The process of repentance and return to God is beautifully reflected in the change in physical orientation of movement as the endowment progresses. For example, when we leave the telestial glory of the world room and enter the terrestrial room in the Salt Lake Temple, we make a 180-degree U-turn from west to east. After making the turn, we are no longer moving away from God but instead drawing near to Him again. In other modern temples, the change in orientation after leaving the telestial world is represented symbolically rather than literally.

Figure 5 shows how a “two-way” temple journey in Nephite temples and the temple of Solomon—outward-bound followed by inward-bound—could have been accommodated without requiring a doubling of sacred spaces. In trying to imagine such a scenario, Latter-day Saint scholar David Calabro has argued, speculatively, that specific narrative features of Moses 2–6 could have been linked to architectural features of Solomon’s temple (or, for that matter, Nephite temples) in ways that reflect its relevance to the outward-bound sequence of [Page 187]the endowment.57 In this conception, something like an earlier version of Moses 2–4, a narrative relating the Creation and the Fall, would have been dramatized as part of an outward-bound progression within the temple. Likewise, something like an earlier version of Moses 5 could have been staged near the altar of sacrifice, and Moses 6 near the laver. Going further, although Calabro did not explicitly discuss the possibility, it could be easily imagined that an older text roughly analogous to Moses 7 could have been used after that point to accompany the culminating inward-bound endowment sequence.58

Figure 5. Conjectural layout of Nephite temples showing outbound and inbound directions. Nephite temples seem to have differed from Israelite temples in their two-way journey (1), Melchizedek priesthood investiture (2), and meeting at the veil (3).

The journey of the inward-bound sequence would have begun with faith and repentance (symbolized at the altar of sacrifice) and baptism (symbolized by the laver). This prepared worshipers who had been thus justified to enter the temple through its first curtain or “gate.” As they approached the veil by traversing the Holy Place, they would have encountered symbols of sanctification in the light of the lampstand, the temple shewbread, and the incense altar. Finally, having consecrated their all and called upon the Lord in prayer, worshipers would have been prepared to figuratively enter the presence of the Lord and continue their ritual preparations for exaltation.

2. Melchizedek Priesthood Investiture and “Second Sacrifice” at the Altar of Incense. While the initial blessing of justification comes exclusively by means of a substitutionary offering on the altar of sacrifice in the temple courtyard—“relying wholly upon the merits of him who is mighty to save” (2 Nephi 31:19)—the culminating step of the process of sanctification in Melchizedek priesthood temple rites can be viewed as a joint effort,59 symbolized by a “second sacrifice”60 made on the altar of incense that stands before the veil.61 While that second sacrifice is no less dependent on the “merits, and mercy, and grace” of Christ (2 Nephi 2:8) and the ongoing endowment of His strengthening power, it requires in addition that individuals grow in their capacity to meet the stringent measure of self-sacrifice62 enjoined by the law of consecration as exemplified by Nephi and his companions in their soul-saving labor on behalf of their “children” and “brethren”—“for we [Page 188]know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23, emphasis added).63

3. Conversing with the Lord at the Veil. In Hugh Nibley’s interpretation of the Septuagint version of Exodus 29:42, the Lord promises that at the tent of meeting: “I shall make myself known to you that I might converse with you.”64 The mention that God would “converse” with His people is reminiscent of Doctrine and Covenants 124:39, which speaks of similar encounters that were to take place in the Nauvoo Temple. These are described by the Lord as “oracles in your most holy places wherein you receive conversations.”65

However, as part of the general withdrawal of the Melchizedek priesthood ordinances from Israelite temples that is documented in ancient sources and modern revelation,66 there was a loss of narrative, signs, and tokens relating to the higher priesthood that included the final atoning rites at the veil. According to Nibley, “the loss of the old ceremonies occurred shortly after Lehi left Jerusalem” and “the ordinances of atonement were, after Lehi’s day, supplanted by allegory.”67 By way of contrast, in describing the temples that the Nephites built “after the manner of the temple of Solomon” (2 Nephi 5:16). Nibley wrote,68

Let us recall that Lehi and his people who left Jerusalem in the very last days of Solomon’s temple were zealous in erecting altars of sacrifice and building temples of their own. It has often been claimed that the Book of Mormon cannot contain the “fulness of the gospel,” since it does not have temple ordinances. As a matter of fact, they are everywhere in the book if we know where to look for them, and the dozen or so discourses on the Atonement in the Book of Mormon are replete with temple imagery.

From all the meanings of kaphar and kippurim69 [Hebrew words relating to the atonement in Israelite temples] we concluded that the literal meaning of kaphar and kippurim is a close and intimate embrace, which took place at the kapporeth or the front cover or flap of the Tabernacle or tent [“later the veil of the temple”70].71 The Book of Mormon instances are quite clear, for example, “Behold, he sendeth an invitation unto all men, for the arms of mercy are extended towards them, and he saith: Repent, and I will receive you” (Alma 5:33). “But behold the Lord hath redeemed my soul from hell; I have beheld his glory, and I am encircled eternally [Page 189]in the arms of his love” (2 Nephi 1:15). To be redeemed is to be atoned. From this it should be clear what kind of oneness is meant by the Atonement—it is being received in a close embrace of the prodigal son, expressing not only forgiveness but oneness of heart and mind that amounts to identity.

Taken together, the scant, allusive, but suggestive evidence in the Book of Mormon72 and the book of Hebrews73 seem to confirm Nibley’s description of the older culminating rites of the Melchizedek Priesthood at the veil that symbolized sanctification through the once-and-for-all atonement of Jesus Christ rather than through the annual Day of Atonement rites of the Aaronic priesthood that were performed at the mercy seat. Similar ordinances constitute the ultimate symbolism of atonement we encounter in the culminating rites of the modern temple endowment as well as in some ancient Near East kingship ceremonies that go back four millennia (Doctrine and Covenants 84:33–48).74

The relevant imagery in Hebrews 6:18–20, which suggests a literal encounter between the initiate and the Lord at the veil, should also be noted:75

Here, then, are two irrevocable acts . . . to give powerful encouragement to us, who have claimed his protection by grasping the hope set before us. That hope we hold. It is like an anchor for our lives, an anchor safe and sure. It enters in through the veil, where Jesus has entered on our behalf as a forerunner, having become a high priest forever after the order of Melchizedek.

The terse prose of this verse bears some unpacking, in which we will draw largely on commentary from non-Latter-day Saint scholars. Anticipating the blessings described in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood,76 the author of Hebrews assures the Saints of the firmness and unchangeableness of God’s promises. The “two irrevocable acts” mentioned are “God’s promise and the oath by which He guarantees that promise,”77 the latter constituting the means by which one’s calling and election is made “sure.”78 In reading verses 18–20, we are meant to understand that so long as we hold fast to the Redeemer, who has entered “through the veil on our behalf . . . as a forerunner,” we will remain firmly anchored to our heavenly home, and the eventual realization of the promise “that where I am, there ye may be also” (John 14:3).79 Undoubtedly, there is also the sense that “Jesus, the high priest, [Page 190][stands] behind the veil in the Holy of Holies to assist those who [pass] through.”80 “The anchor would thus constitute the link that ‘extends’ or ‘reaches’ to the safe harbor of the divine realms . . . providing a means of access by its entry into God’s presence.”81 As Jesus was “exalted” . . . above the entire created order—to the heavenly throne at God’s right hand,” so “humanity will be elevated to the pinnacle of the created order”82 as sons and daughters of God.83 And as the Son received “all the glory of Adam,”84 so “his followers will also inherit this promise if they endure . . . testing.”85

It is apparent that Joseph Smith anticipated a conversation of God’s elect with the Lord at the “veil” of the “heavenly temple” long before he got to Nauvoo. This heavenly assurance of exaltation, “confirmed . . . by an oath” (Hebrews 6:17), is described in a letter he wrote to his uncle Silas on 26 September 1833:86

Paul said to his Hebrew brethren that God being more abundantly willing to show unto the heirs of his promises the immutability of his council “confirmed it by an oath” (Hebrews 6:17). He also exhorts them who through faith and patience inherit the promises.

“Notwithstanding we (said Paul) have fled for refuge to lay hold of the hope set before us, which hope we have as an anchor of the soul both sure and steadfast, and which entereth into that within the veil” (Hebrews 6:18–19). Yet he was careful to press upon them the necessity of continuing on until they as well as those who then inherited the promises might have the assurance of their salvation confirmed to them by an oath from the mouth of Him who could not lie, for that seemed to be the example anciently and Paul holds it out to his brethren as an object attainable in his day.

And why not? I admit that, by reading the scriptures of truth, saints in the days of Paul could learn beyond the power of contradiction that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had the promise of eternal life confirmed to them by an oath of the Lord, but that promise or oath was no assurance to them of their salvation. But they could, by walking in the footsteps and continuing in the faith of their fathers, obtain for themselves an oath for confirmation that they were meet to be partakers of the inheritance with the Saints in light.

Later, on 14 May 1843, the Prophet gave a Nauvoo sermon similarly [Page 191]describing how one’s calling and election is made sure. Though more detailed in its descriptions, Joseph Smith’s teachings in this sermon are entirely consistent with his 1833 letter to Silas.87

The Nephite (and Temple) Manner of Teaching the Plan of Salvation. Throughout the Book of Mormon and in other places in modern scripture the plan of salvation is often taught using the same general three-part outline that is given in the temple endowment, namely Creation, Fall, and the Atonement of Jesus Christ.88 In describing this teaching approach, Elder Bruce R. McConkie liked to speak of its emphasis on the “three pillars” of eternity.89 This “Christ-centered” presentation of the plan of salvation is a stark contrast to the “location-centered” diagram that is used widely in classroom settings to illustrate the sequence of events that chart the journey of individuals from premortality to the resurrection. Nathan Richardson observed that in the location-centered diagram there is no mention of Jesus Christ and His role as Savior and Redeemer—thus leaving out the very heart of the Plan.90

Going further, in a brilliant article entitled “Lehi’s Dream, Nephi’s Blueprint,”91 Noel B. Reynolds argues that Lehi and Nephi received the same vision and that the teachings of what they learned about the covenant path that leads to the tree of life echoed for a thousand years throughout the rest of the Book of Mormon.92 Building on insights from Reynolds, as well as Joseph Spencer93 and Neal Rappleye,94 one might straightforwardly conclude that the elements of the vision constituted a sort of heavenly endowment for Lehi and Nephi—analogous to the experiences of Moses and Abraham at formative junctures in their respective ministries.95

Significantly, the three major themes of Lehi’s and Nephi’s dreams are the “three pillars of eternity” (see figure 6) correspond to the three phases of the modern endowment:

Figure 6. The three pillars of eternity as reflected in the dream of Lehi and vision of Nephi. Left, Gustave Doré, The Empyrean, 1857.98 Center, Brad Teare, Allegory of the Olive Tree.99 Right, Jachoon Choi, Tree of Life.100

- the blueprint of Creation revealed in the presence of God and His angels as described in greatest detail in Lehi’s dream;96

- a sketch of “salvation history” as acted out in the telestial world—apostasy and dispensational restoration through the labors of God’s servants as summarized in Lehi’s and Nephi’s visions (1 Nephi 12–14)97 and graphically illustrated in all its phases in Jacob’s allegory of the olive tree (Jacob 5);

- [Page 192]the covenant path in the terrestrial world that parallels an iron rod that leads to the Tree of Life in the celestial world. This theme is most thoroughly outlined in Lehi and Nephi’s dreams (1 Nephi 8, 11)101 and the accompanying personal explanations given to him by the Father and the Son.102

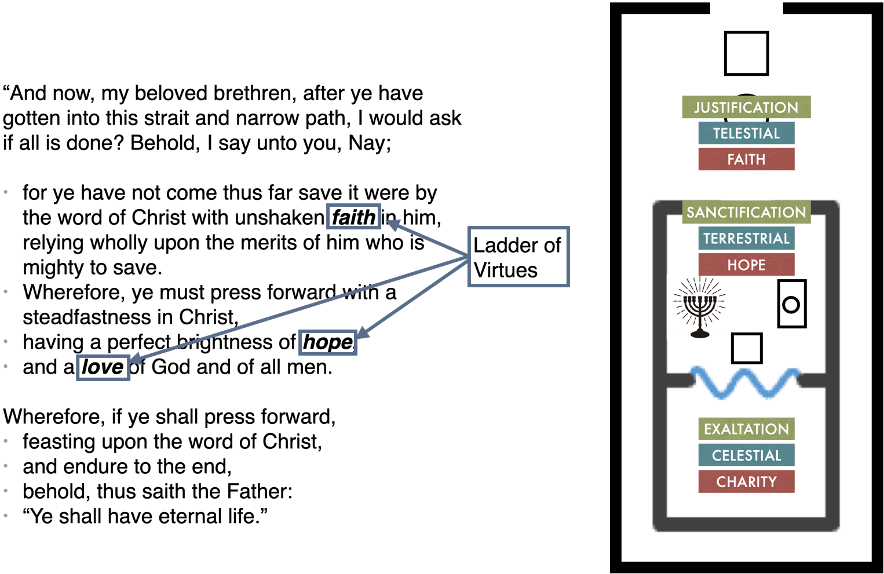

Mapping the three cardinal virtues, the three degrees of glory, and the three progressive stages of discipleship to the journey through the three areas of the temple. In our scan of 2 Nephi 31:19–20, the first thing we notice is that three important Christlike attributes or virtues—faith, hope, and charity—have been unobtrusively inserted into the text in their natural order, suggesting a progression that can be seen as successively highlighting the different areas of the temple in which the ordinances and covenants relevant to each virtue are introduced.103

Going further, Joseph Smith related the three cardinal virtues of the ladder of exaltation to the three different areas of the temple when he taught that “the three principal rounds [or rungs] of Jacob’s ladder are the telestial, the terrestrial, and the celestial glories or kingdoms."104 Because these three kingdoms are represented in the temple, Joseph Smith also equated the symbolism of Jacob’s ladder to the “mysteries of godliness.”105

Figure 7. The three cardinal virtues, the three degrees of glory, and the three progressive stages of discipleship mapped to the three areas of the temple.

Finally, the three different areas of ancient temples are symbolized in different kinds of sacrifices that relate to the three progressive [Page 193]stages of justification, sanctification, and, ultimately, exaltation. This is explained in the following excerpt from the Latter-day Saint Bible Dictionary:106

It is noteworthy that when the three offerings were offered together, the sin always preceded the burnt, and the burnt the peace offerings. Thus, the order of the symbolizing sacrifices was the order of atonement [justification], sanctification [culminating in complete consecration at the altar of incense in front of the second veil107], and fellowship with the Lord [exaltation].

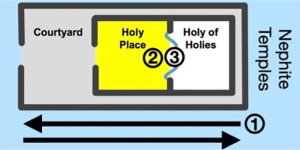

Nephi’s description of the inbound temple journey. Now let’s look at 2 Nephi 31:19–20 in more detail.108 In prior verses, Nephi has already exhorted his readers to “follow the Son, with full purpose of heart” (2 Nephi 31:13) and to enter the gate of “repentance and baptism by water” (2 Nephi 31:17). The altar of sacrifice and the laver that sit in the courtyard, outside the temple door, evoke these two themes. Nephi teaches that baptism, in turn, prepares his readers to receive “a remission of . . . sins by fire and by the Holy Ghost” (2 Nephi 31:17). Then, Nephi weaves the single mention of faith, hope, and love within these chapters into a masterful description of the culminating sequence [Page 194]of the pathway to eternal life that leads through the ancient temple (please refer to the numbered annotations in figure 8):

Figure 8. Correlation of faith, hope, and love in 2 Nephi 31:19–20 to the different areas of the temple.

- Nephi begins with a description of the “gate of baptism” that most of his readers have probably already entered. They have “come thus far” through “unshaken faith” in Christ, being justified through “relying wholly upon the merits of him who is mighty to save.” The gate of baptism, the last requirement governing entrance through the temple door, brings us out of the telestial world (Doctrine and Covenants 76: 81–90, 98–106) and into the terrestrial glory that fills the Holy Place of the temple.

- Nephi says that we must “press forward”—which evidently means that we are to advance steadfastly along the high priestly way of the Holy Place toward greater light and knowledge. The same phrase about “pressing forward” is used earlier by Nephi’s father in his account of the vision of the tree of life (1 Nephi 8:21, 24, 30; see figure 9). He said that “multitudes” were “pressing forward; and they came and caught hold of the end of the rod of iron; and they did press their way forward, continually holding fast to the rod of iron, until they came forth and fell down and partook of the fruit of the tree” (1 Nephi 8:30). Lehi is very particular about his description, writing twice that the people “caught hold of the end of the rod of iron” (1 Nephi 8:24, [Page 195]30). To me, the language about catching hold of the “end” of the rod of iron suggests the necessity of beginning the covenant path by entering in at the gate of baptism. This could be taken as implying that people couldn’t begin their journey by grabbing hold of the rod at a random spot in the middle, but instead “caught hold of the end of the rod of iron.”

- The lamp in the Holy Place symbolizes our quest to attain a “perfect brightness of hope,” the culmination of a lifelong increase of the enlightening and sanctifying influence of the Spirit that culminates in “a fulness of the Holy Ghost” (Doctrine and Covenants 109:15).

- Faithfulness to the last and most difficult law of consecration, symbolized by the incense offering at the altar in front of the second veil,110 requires the development of charity, “a love of God and of all men.”

- The complete sanctification that is required of all who would enter the kingdom of heaven requires “feasting upon the word of Christ” and is symbolized by the temple shewbread that was eaten by the temple priests and their [Page 196]family each week. Non-Latter-day Saint scholars have compared this symbol to the eucharist (the counterpart to the Latter-day Saint sacrament of bread and water)111 a “repeated maintenance ritual”112 associated symbolically with the bread and wine of the table of shewbread.

- In scripture, “the end” usually refers to the end of one’s probation, the moment when Saints will have been prepared to meet God at the veil.113

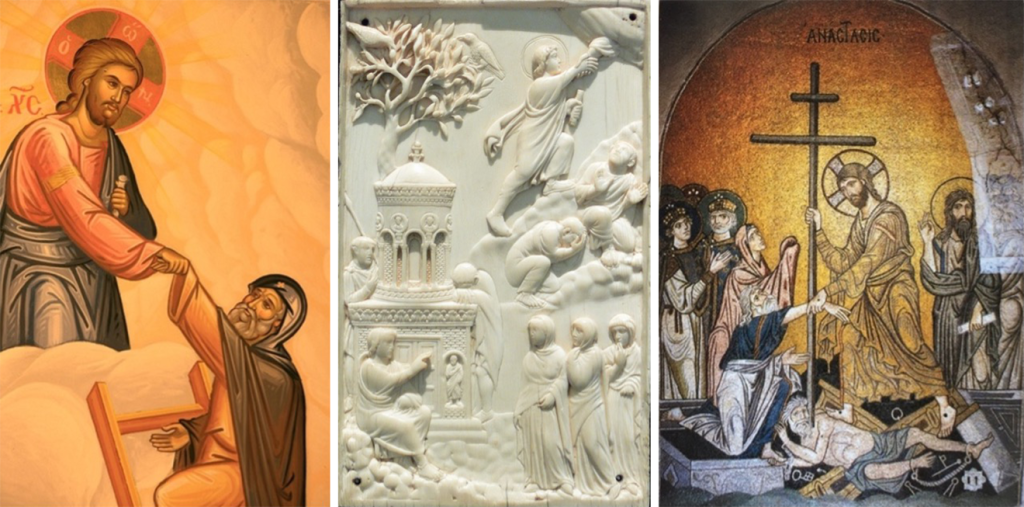

- In a divine face-to-face encounter at the heavenly veil, those who have endured faithfully to the end of their probation will receive the sure oath of the Father: “Ye shall have eternal life.” An essay analyzing Joseph Smith’s 21 May 1843 discourse on 2 Peter 1—the context in which the Prophet’s mention of the three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder appeared—identifies the oath described in 2 Nephi 31:20 (“Ye shall have eternal life”; compare Psalm 110:4114) as the “more sure word of prophecy” (defined in the discourse as being “the voice of Jesus saying my beloved thou shalt have eternal life”).115 By equating these concepts, the teachings of Joseph Smith confirm that not only sacred gestures (such as those shown in figure 10 and described in Hebrews 6:18–20116) but also sacred words are exchanged at the top of the ladder of exaltation. Thus, the Prophet endowed ritual teachings of temple ordinances with literal significance in the context of actual heavenly ascent.117 With the ritual atonement being symbolically represented at the veil rather than in the Holy of Holies, the symbolism of the celestial room of modern temples is transformed from the solemn, solitary locus of annually repeated atoning ritual described in the Old Testament into a joyful meeting place that represents eternal “fellowship with the Lord.”118

Figure 9. Jachoon Choi, The Tree of Life.109

Figure 10. Three mutually illuminating images shed light on the significance of Christian conceptions of the culminating step of ritual ascent and its counterpart in actual heavenly ascent. Left: Greek Orthodox icon depicting the ladder of virtues.119 In many depictions of the ladder of virtues, Christ is positioned at the top of the ladder taking the ascending disciple by the wrist. Center: The Woman at the Tomb and the Ascension, ca. 400. (Public domain.) A similar grasping gesture is shown where Christ is welcomed to heaven after his ascension. Right: Anastasis, Daphni Monastery, near Athens, Greece, ca. 1080–1100.120 Nicoletta Isar brilliantly concludes that the gesture of the hand of Christ grasping the wrist of Adam, “an anchor . . . sure and steadfast” (Hebrews 6:19) that binds them together in unbreakable fashion, represents not only the “meeting ground of both life and death,” but also serves as a “visual metaphor of the . . . nuptial bond,”121 an equally indissoluble union, “the conjugal harness by which both parts are yoked together.”122 This metaphor is visually highlighted by the stigma on the hand of the Savior that is carefully positioned at the center of the image to overlay both the cross of Christ and the wrist of Adam.123

Nephi paints a stunning word picture of exactly what this moment looks like in his anguished psalm of deliverance: “O Lord, wilt thou encircle me around in the robe of thy righteousness!” (2 Nephi 4:33). The moment suggests the loving embrace of the prodigal son, illustrated in figure 11. In the words of his plea for deliverance, Nephi drew on the culture of the desert. Fleeing to the tent of a sheikh who will defend him against his enemies, the weary fugitive humbly kneels and tells his would be protector, “I am your suppliant.” Honor impels the [Page 197]sheikh to put the hem of his great hooded robe over the suppliant’s shoulder with a promise of protection, “This is your tent, this is your family. We’ll make a place for you.”124

Nephi’s eloquent two-verse exposition in 2 Nephi 31:19–20 provides strong support for the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon and the idea that it contains the fulness of what Jacob 7:6 calls “the gospel, or the doctrine of Christ,” including detailed descriptions of the significance and sequence of temple ordinances. These teachings were not withheld until Joseph Smith and the Saints arrived in Nauvoo but rather were made available the Prophet very early in his ministry as he translated the Book of Mormon.125

[Page 198]

Figure 11. Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787): The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1773.126

[Author’s Note: This essay expands on an earlier version of this paper that was published in Meridian Magazine (https://latterdaysaintmag.com/the-covenant-path-in-2-nephi-3119-20/) as well as [Page 199]material from my book on Freemasonry and the Origins of Latter-day Saint Temple Ordinances. Thanks to the many friends, both explicitly mentioned below and unnamed, who made helpful suggestions on earlier versions of some of this material, including Rebecca Lambert, who offered many helpful comments and shepherded final changes to this version for journal publication.]

In his careful paraphrase of Paul’s description of faith, hope, and charity within the thirteenth Article of Faith, Joseph Smith pointedly distinguished between the early Saints’ previous attainments with respect to the first ladder rungs of faith (“We believe all things”) and hope (“we hope all things”), and their unfulfilled aspirations as they climbed toward the last, hardest rung of charity: “we have endured many things, and hope to be able to endure all things.” With happy anticipation, the last Article of Faith looks forward to the brighter day when the Saints will be able to endure all things—to complete the climb of the ladder of heavenly ascent “by the patience of hope and the labor of love” (“Come, Let Us Anew,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), 217, stanza 1. See 1 Thessalonians 1:3).

Note that Joseph Smith could not have been aware of the triad of virtues that appeared in Hebrews 10:22–24, as the King James Bible, unlike most modern translations, uses “faith” in place of “hope” in v. 23.

Note that in this conception of creation the focus is not on the origins of the raw materials used to make the universe, but rather their fashioning into a structure providing a useful purpose. The key insight, according to Walton, is that: “people in the ancient world believed that something existed not by virtue of its material proportion, but by virtue of its having a function in an ordered system . . . Consequently, something could be manufactured physically but still not ‘exist’ if it has not become functional. . . . The ancient world viewed the cosmos more like a company or kingdom” that comes into existence at the moment it is organized, not when the people who participate it are created materially (Walton, Lost World of Genesis One, 26, 35. See Smith, Teachings, 181, Abraham 4:1).

Walton continues:

[Page 207]It has long been observed that in the contexts of bara’ [the Hebrew term translated “create”] no materials for the creative act are ever mentioned, and an investigation of all the passages mentioned above substantiate that claim. How interesting it is that these scholars then draw the conclusion that bara’ implies creation out of nothing (ex nihilo). One can see with a moment of thought that such a conclusion assumes that “create” is a material activity. To expand their reasoning for clarity’s sake here: Since “create” is a material activity (assumed on their part), and since the contexts never mention the materials used (as demonstrated by the evidence), then the material object must have been brought into existence without using other materials (that is, out of nothing). But one can see that the whole line of reasoning only works if one can assume that bara’ is a material activity. In contrast, if, as the analysis of objects presented above suggests, bara’ is a functional activity, it would be ludicrious to expect that materials are being used in the activity. In other words, the absence of reference to materials, rather than suggesting material creation out of nothing, is better explained as indication that bara’ is not a material activity but a functional one (Walton, Lost World of Genesis One, pp. 43–44).

In summary, the evidence . . . from the Old Testament as well as from the ancient Near East suggests that both defined the pre-creation state in similar terms and as featuring an absence of functions rather than an absence of material. Such information supports the idea that their concept of existence was linked to functionality and that creation was an activity of bringing functionality to a nonfunctional condition rather than bringing material substance to a situation in which matter was absent. The evidence of matter (the waters of the deep in Genesis 1:2) in the precreation state then supports this view” (Walton, Lost World of Genesis One, p. 53).

In another correspondence between these events, Mark Smith notes a [Page 208]variation on the first Hebrew word of Genesis (bere’shit) and the description used in Ezekiel 45:18 for the first month of a priestly offering (bari’shon): “‘Thus said the Lord: ‘In the beginning (month) on the first (day) of the month, you shall take a bull of the herd without blemish, and you shall cleanse the sanctuary.’ What makes this verse particularly relevant for our discussion of bere’shit is that ri’shon occurs near ’ehad, which contextually designates ‘(day) one’ that is ‘the first day’ of the month. This combination of ‘in the beginning’ (bari’shon) with ‘(day) one’ (yom ’ehad) is reminiscent of ‘in beginning of’ (bere’shit) in Genesis 1:1 and ‘day one’ (yom ’ehad) in Genesis 1:5” (Mark S. Smith, The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1 [Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010], 47).

Hahn notes the same correspondences to the creation of the cosmos in the building of Solomon’s Temple (Scott W. Hahn, “Christ, Kingdom, and Creation: Davidic Christology and Ecclesiology in Luke-Acts,” Letter and Spirit 3 [2007], 176–77. See Morrow, “Creation”; Levenson, “Temple and World”, 283–84; Crispin H. T. Fletcher-Louis, All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls [Leiden, NL: Brill, 2002), 62–65; Weinfeld, “Sabbath, Temple and the Enthronement of the Lord: The Problem of Sitz Im Leben of Genesis 1:1–2:3,” 506, 508):

As creation takes seven days, the Temple takes seven years to build (1 Kings 6:38). It is dedicated during the seven-day Feast of Tabernacles (1 Kings 8:2), and Solomon’s solemn dedication speech is built on seven petitions (1 Kings 8:31–53). As God capped creation by “resting” on the seventh day, the Temple is built by a “man of rest” (1 Chronicles 22:9) to be a “house of rest” for the Ark, the presence of the Lord (1 Chronicles 28:2; 2 Chronicles 6:41; Psalm 132:8, 13–14; Isaiah 66:1).

When the Temple is consecrated, the furnishings of the older Tabernacle are brought inside it. (R. E. Friedman suggests the entire Tabernacle was brought inside). This represents the fact that all the Tabernacle was, the Temple has become. Just as the construction of the Tabernacle of the Sinai covenant had once recapitulated creation, now the Temple of the Davidic covenant recapitulated the same. The Temple is a microcosm of creation, the creation a macro-temple.

Narrative features of the Book of Moses described by Calabro that would have been relevant to its use as a temple text include lamination of discourse frames; verbs of motion, repeated themes, and wordplays that relate to temple architecture; and narrative displacement.

As a specific example, consider that the mention that “the Holy Ghost fell upon Adam” occurs in Moses 5:9, while the story of his baptism is “put in the mouth of Enoch, several pages later” (Calabro, “Joseph Smith and the Architecture,” 173). Calabro hypothesizes that its “position in chapter 6 conforms to the setting of the ritual, near the laver, where instruction about baptism is appropriate.” Similarly, Adam and Eve are taught the law of sacrifice only after they have been driven out of the Garden, allowing those who, according to Calabro’s conjecture, were participating in temple ritual to be situated near the altar of sacrifice before the presentation of that law.

Just as Jesus Christ will put all enemies beneath his feet (1 Corinthians 15:25–26), so Joseph Smith taught that each person who would be saved must also, with His essential help, gain the power needed to “triumph over all [their] enemies and put them under [their] feet” (Smith, Teachings, 297. See also 301, 305), possessing the “glory, authority, majesty, power, and dominion which Jehovah possesses” (Larry E. Dahl and Charles D. Tate, Jr., eds., The Lectures on Faith in Historical Perspective, Religious Studies Specialized Monograph Series [Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1990], 7:9, 98. See 7:16—note that it is not certain whether Joseph Smith authored these lectures).

As Chauncey Riddle explains (Chauncey C. Riddle, “The New and Everlasting Covenant,” in Doctrines for Exaltation: The 1989 Sperry Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989], 228), “the covenant of baptism is [not only ] our pledge to seek after good and to eliminate all choosing and doing of evil in our lives, [but] also our receiving the power to keep that promise,” that is, through the gift of the Holy Ghost. For Latter-day Saints, Jesus Christ is not only their Redeemer but also their literal prototype, the One who demonstrates the process of probation that all people must pass through as they follow Him (Matthew 4:19; 8:22; 9:9; 16:24; 19:21; Mark 2:14; 8:24; 10:21; Luke 5:27; 9:23, 59, 61; 18:22; John 1:43; 10:27; 12:26; 13:36; 21:19, 22).

As we approach the second barrier of sacrifice, we move symbolically from the moon to the sun. All of the moon’s light is reflected from the sun—it is borrowed light [See Book of Abraham, explanation of Facsimile 2, Figure 5].

Heber C. Kimball used to say that when life’s greatest tests come, those who are living on borrowed light— the testimonies of others—will not be able to stand (Orson F. Whitney, The Life of Heber C. Kimball, 2nd ed. [Salt Lake City: Stevens & Wallis, 1945], pp. [Page 212]446, 449–50; J. Golden Kimball, “Discourse, 8 April 1906, Overflow Meeting in the Assembly Hall,” in Seventy-Sixth Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, ed. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [Salt Lake City: The Deseret News, 1906], pp. 76–77; “Discourse, 4 October 1930,” in One-Hundred and First Semi-Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, ed. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930], pp. 59–60; Harold B. Lee, “Watch! Be Ye Therefore Ready,” Improvement Era 68, no. 12 [1965]: 1152. Compare Brigham Young, “Necessity for a Reformation a Disgrace; Intelligence a Gift, Increased by Imparting; Spirit of God; Variety in Spiritual as Well as Natural Organizations; God the Father of the Spirits of All Mankind, Etc. [Discourse Delivered in Great Salt Lake City, 8 March 1857],” in Journal of Discourses [repr. 1853–1886; Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1966], 265–66; Amasa M. Lyman, “Mormonism and Its Results; Internal Light and Development; Decrease of Evil; the Fountain of Light [a Discourse by Elder Amasa Lyman, Delivered in the Bowery, Great Salt Lake City, July 12, 1857],” in Journal of Discourses, 36–38; Orson Hyde, “The Way to Eaternal Life; Practical Religion; All Are Not Saints Who Profess to Be; Prison-House of Disobedient Spirits [a Discourse by Elder Orson Hyde, Delivered in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, March 8, 1857],” in Journal of Discourses, 71–72; Charles W. Penrose, “Sincerity Alone Not Sufficient; the Gathering Foretold; Inspired Writings Not All Contained in the Bible; Province of the Holy Ghost; the Reformers; Confusion of Sects; Apostate Condition of the World Foretold; How the Apostles Were Sent out; Authority Required; What the Saints Should Do; Opposition to the Gospel, Ancient and Modern; Testimony (Discourse by Elder Chas. W. Penrose, Delivered in the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Sunday Afternoon, May 20th, 1883),” in Journal of Discourses, 41. See also Matthew 25:1–13). We need our own access to the light of the Son.

Baptism represents the first sacrifice. The temple endowment represents the second sacrifice. The first sacrifice was about breaking out of Satan’s orbit. The second one is about breaking fully into Christ’s orbit, pulled by His gravitational power. The first sacrifice was mostly about giving up temporal things. The second one is about consecrating ourselves spiritually, holding back nothing. As Elder Maxwell said, the only thing we can give the Lord that He didn’t already give us is our own will. Neal A. Maxwell, “Jesus, the Perfect Mentor,” Ensign, February 2001, 17.

Seeking to be meek and lowly, disciples gladly offer God their will. As our children sing, “I feel my Savior’s love. . . . / He knows I will follow him, / Give all my life to him” (Children’s Songbook, “I feel my Savior’s love,” 74–75). And then what happens? In President Benson’s words, “When obedience ceases to be an irritant and becomes our quest, in that moment God will endow us with power” (cited in Donald L. [Page 213]Staheli, “Obedience—Life’s Greatest Challenge,” Ensign 28, May 1998, 82).

Before [the author of Hebrews] sounds the familiar note of Christ’s exalted status [which is, incidentally, the theme of the first verses of Alma 13], our author reverts to the results of the self-sacrificial act by which that status is achieved.

It is in this sense that the Lord can say, despite the fact that it is His sacrifice that ultimately makes us holy, “sanctify yourselves” (for example Exodus 19:22; Leviticus 11:44, 20:7; Numbers 11:18; Joshua 3:5, 7:13; 1 Samuel 16:5; 1 Chronicles 15:12, 14; 2 Chronicles 29:5, 15, 34; 30:3, 8, 15, 24; 31:18; 35:6; Isaiah 66:17; Doctrine and Covenants 43:11, 16; 88:68, 74; 133:4, 62. See also John 17:19; 2 Timothy 2:21).

I understand the preposition “after” in 2 Nephi 25:23 to be a preposition of separation rather than a preposition of time. It denotes logical separateness rather than temporal sequence. We are saved by grace “apart from all we can do,” or “all we can do notwithstanding,” or even “regardless of all we can do.” Another acceptable paraphrase of the sense of the verse might read, “We are still saved by grace, after all is said and done.”

For additional discussion of this verse in the context of general discussions of divine grace, see Bruce C. Hafen, The Broken Heart (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 155–56; Brad Wilcox, “His Grace Is Sufficient,” speeches.byu.edu/talks/brad-wilcox/his-grace-is-sufficient/; Joseph M. Spencer, “What Can We Do? Reflections on 2 Nephi 25:23,” Religious Educator 15, no. 2 (2014), rsc.byu.edu/vol-15-no-2-2014/what-can-we-do-reflections-2-nephi-2523. Two excellent studies by Jared Ludlow and Daniel O. McClellan have gone further to place the scripture in its required literary context: Daniel O. McClellan, “2 Nephi 25:23 in Linguistic and Rhetorical Context” (Presentation, ‘Book of Mormon Studies: Toward a Conversation’ Conference, Utah State University, Logan, Utah, October 12–13, 2018),”; McClellan, “Despite All We Can Do,” LDS Perspectives, 18 March 2020, interpreterfoundation.org/ldsp-despite-all-we-can-do-with-daniel-o-mcclellan/).

[Page 214]Although Alma 24:10–11 defines “all we could do” [note the past tense, emphasis added] solely in terms of repentance, I believe that one of the purposes of the process of sanctification is to allow us to grow in holiness, gradually acquiring a capacity for doing “more”—specifically, becoming “good” like our Father (see Matthew 19:17; Mark 10:18; Luke 18:19) and “doing good” (Acts 10:38, emphasis added) like the Son, an evolution of our natures jointly enabled by the Atonement and our exercise of moral agency.

Despite all this, of course, it must never be forgotten that even repentance itself, which is “all we can do” at the time we first accept Christ, would be impossible had not the merciful plan of redemption been laid before the foundation of the world (Alma 12:22–37). And, of course, it is His continuous grace that lends us breath, “preserving [us] from day to day, . . . and even supporting [us] from one moment to another” (Mosiah 2:21).

The kapporeth is usually assumed to be the lid of the Ark, yet it fits much better with the front, since one stands before it.

Nibley gives further arguments for his interpretation in “Atonement”, 610n13.

Comparing the symbol of the anchor to an image in Virgil, Witherington concludes that he was “thinking no doubt of an iron anchor with two wings rather than an ancient stone anchor” (Ben Witherington III, Letters and Homilies for Jewish Christians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Hebrews, James and Jude [Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2007], 225). The shape of the anchor recalls both the covenant and the oath by which the former is “made sure” (2 Peter 1:10).

The symbol of the anchor evokes the tradition of pounding nails into the Western Wall of the Jerusalem Temple. Daniel Rona writes: “Older texts reveal a now forgotten custom of the ‘sure nails.’ This was the practice of bringing one’s sins, grief, or the tragedies of life to the remains of the temple wall and [Page 216]‘nailing’ them in a sure place. The nails are a reminder of Isaiah’s prophecy [22:23–25] that man’s burden will be removed when the nail in the sure place is taken down” (Daniel Rona, Israel Revealed: Discovering Mormon and Jewish Insights in the Holy Land [Sandy, UT: The Ensign Foundation, 2001], 194). Christian use of anchor imagery goes back to “the first century cemetery of St. Domitilla, the second and third century epitaphs of the catacombs” (“Christian Symbols,” FishEaters [website], fisheaters.com/symbols.html). Although the anchor is frequently depicted in connection with a figure representing the Hope afforded by Jesus Christ, it is, from the perspective of those who aspire to a place in God’s presence, an even more appropriate companion to the crowning blessings associated with the requirement of Charity, as shown in a stained glass panel by Ward and Hughes from the cathedral in Lichfield, England (Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure 6–13, 472). In 2 Nephi 31:20, Nephi associates this “love of God and of all men” with the ultimate attainment of both a “perfect brightness of hope” and the sure promise of the Father (“Ye shall have eternal life”).

While literary and visual artists continue to find inspiration in the human dramas retold throughout the book, the text itself features visualizations of its basic doctrinal messages: (1) God on his throne in heavenly council, (2) the tree of life with the straight and narrow path, the iron rod, and the great and spacious building, and (3) the allegory of the olive tree. As I will explain below, those three visual images are part of Lehi’s and Nephi’s great vision and provide the blueprint for the complex of covenant history and doctrinal teaching recorded by multiple authors throughout the entire book.

Speaking specifically of the importance of 2 Nephi 31, Reynolds writes in “The Gospel According to Nephi: An Essay on 2 Nephi 31,” Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Resotred Gospel 16, no. 2 (2015), 53–54, 69, rsc.byu.edu/vol-16-no-2-2015/gospel-according-nephi-essay-2-nephi-31:

Second Nephi 31 is . . . the earliest comprehensive statement of the gospel message in the Book of Mormon—even though several previous passages make it clear that Lehi, Nephi, and Jacob knew the gospel—as it clearly sets forth all six elements of that message as it is recognized in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints today, including:

1. Faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

2. Repentance.

3. Baptism of water.

4. Gift of the Holy Ghost.

5. Enduring to the end.

6. Eternal life.

These same six elements are included in both of the other Book of Mormon presentations of the gospel or doctrine of Christ that were given by Christ himself. . . .

This passage may have served the Nephite dispensation in much the same way that Joseph Smith’s First Vision has served this last dispensation by providing the highest possible authority for its central claims—including the prophetic claims of the first leader. We find the Nephite prophets across 1000 years of ministry staying true to the concepts and phraseology introduced by Nephi in this passage. This is most clearly reflected in their teachings on the gospel, baptism, and charity. Although we cannot know the extent to which later[Page 218] prophets had access to Nephi’s small plates, it is clear that his phrasing and teachings persist through their writings to the very end of Mormon’s volume.

Spiritual preparation is enhanced by study. I like to recommend that members going to the temple for the first time read short explanatory paragraphs in the Bible Dictionary, listed under seven topics: “Anoint,” “Atonement,” “Christ,” “Covenant,” “Fall of Adam,” “Sacrifices,” and “Temple.” Doing so will provide a firm foundation.”

The eucharist sacrament is another ritual activity referred to by Philip. It seems to correspond to the Holy of the Holy shrine, the shrine closely tied to “redemption” (69:23). Accordingly, this shrine is to be associated with the second room in the Temple, the hekhal or holy place. In the hekhal stood a golden altar for incense offerings (1 Kings 7:48. See 1 Kings 6:20–21), ten lampstands (1 Kings 7:48–49), shulchan ha-panim or the table of the Countenance (1 Kings 7:48–49) upon which was ritually offered lechem ha-panim, the bread of the Countenance. Every Sabbath twelve loaves of unleavened bread [Page 220]were placed on the table before the face of Yahweh (Leviticus 24:5–9). After a week, the loaves were eaten by the priests (Leviticus 6:7–9; 24:5–9). There seems also to be evidence that the priests placed jugs of wine on the Table along with the loaves and then partook of beverage and bread when the time came for them to participate in the weekly meal.

See also Exodus 25:22–29; 37:9–12; Numbers 4:7; 1 Samuel 21:7; 1 Kings 7:34–35; 2 Chronicles 4:19.

unfolds a soteriological symbolism that is parallel to and overlaps with that of baptism–anointing [confirmation, in Latter-day Saint tradition]. . . . The fact that the eucharist has soteriological significance autonomously of the baptism-anointing sequence is probably related to the nature of the eucharist as a repeated maintenance ritual, which makes it functionally distinct from the initiation ritual performed only once for each candidate.”

Sometimes . . . we refer to the first principles as if they represented the entire process of discipleship. When we do that, “endure to the end” can sound like an afterthought, as if our baptism and confirmation have hooked us like a trout on God’s fishing line, and so long as we don’t squirm off the hook, He will reel us safely in. Or some assume that “endure to the end” simply describes the “no worries” stage of life, when our main job is to just enjoy frequent trips to our cozy retirement cottage while refraining from doing anything really bad along the way. (Bruce C. Hafen and Marie K. Hafen, The Contrite Spirit: How the Temple Helps Us Apply Christ’s Atonement [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015], 57–58)

But there is more. As President Russell M. Nelson has said, “Enduring to the end . . . means the endowment and sealing ordinances of the holy temple” “Begin with the end in mind,” Seminar for New Mission Presidents, June 22, 2014. For a summary of Elder Nelson’s talk, see S. J. Weaver, “Begin Missionary Work.” Also Noel and Sydney Reynolds have taught that “endure to the end” is a gospel principle that is paired with the temple endowment, just as repentance is paired with baptism (personal communication, May 17, 2014). Nephi offered a similarly expansive view of “enduring”: we should “endure to the end, in following the example of the Son of the living God” (2 Nephi 31:16). The first principles will always be first—yet they are but the foundation for pressing on toward the Christlike life: “Therefore not leaving the principles of the doctrine of Christ, let us go on unto perfection; not laying again the foundation of repentance from dead works, and of faith toward God, . . . [and] baptisms” (JST Hebrews 6:1–2; emphasis added).

Though [the Saints addressed by Peter] might hear the voice of God and know that Jesus was the Son of God, this would be no evidence that their election and calling was made sure (2 Peter 1:10), that they had part with Christ, and were joint heirs with Him. Then they would want that more sure word of prophecy (2 Peter 1:19), that they were sealed in the heavens and had the promise of eternal life in the kingdom of God.

Then, having this promise sealed unto [us is] an anchor to the soul, sure and steadfast. Though the thunders might roll and lightnings flash, and earthquakes bellow, and war gather thick around, yet this hope and knowledge would support the soul in every hour of trial, trouble, and tribulation. Then knowledge through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is the grand key that unlocks the glories and mysteries of the kingdom of heaven. . . .

Then I would exhort you to go on and continue to call upon God until you make your calling and election sure for yourselves, by obtaining this more sure word of prophecy, and wait patiently for the promise until you obtain it.

Go here to see the 14 thoughts on ““The Covenant Path of the Ancient Temple in 2 Nephi 31:19–20”” or to comment on it.