Abstract: For decades, several Latter-day Saint scholars have maintained that there is a convergence between the location of Nahom in the Book of Mormon and the Nihm region of Yemen. To establish whether there really is such a convergence, I set out to reexamine where the narrative details of 1 Nephi 16:33–17:1 best fit within the Arabian Peninsula, independent of where the Nihm region or tribe is located. I then review the historical geography of the Nihm tribe, identifying its earliest known borders and academic interpretations of their location in antiquity. My investigation brings in data on ancient Yemen and Arabia that has not been previously considered in discussions about Nahom or Lehi’s journey more generally, and leads to some surprising conclusions. Nonetheless, after establishing both where we should expect to find Nahom and the most likely location of ancient Nihm independent of one another, the two locations are compared and found to substantially overlap, suggesting that the “Nahom convergence” is real. With the convergent relationship established, I then explore four possible scenarios for Lehi’s stop at Nahom, the burial of Ishmael, and the party’s journey eastward toward Bountiful based on the new data presented in this paper.

In his seminal work Lehi in the Desert, originally published serially in the 1950 Improvement Era, Hugh Nibley pointed out a subtle detail in the wording of 1 Nephi 16:34: “Note that this is not ‘a place which we called Nahom,’ but the place which was so called.”1 In the mid-1970s, Lynn and Hope Hilton also noticed this detail, and reasoned that Nahom “was almost certainly a settled place, because Nephi says it already ‘was called Nahom,’ while every other campsite … was named by [Lehi’s [Page 2]family] themselves,” leading them to ask: “Called Nahom by whom?”2 As a place name known to others on the Arabian Peninsula, Nahom could possibly be found in other historical sources. Sure enough, a year after the Hiltons published their exploration of Lehi’s trail in the Ensign,3 archaeologist Ross T. Christensen identified the name Nehhm on an old eighteenth century map of Yemen prepared by German explorer and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr and suggested it might be “the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:34).4 In a short note published in the Ensign, Christensen recommended three steps be taken for further research,5 and in the intervening decades, each of his recommended avenues of inquiry have borne significant fruit.6

The first was “to invite semiticists to give their opinions as to whether Nahom and Nehhm are probable phonetic equivalents.”7 Starting with Warren Aston in the 1980s, researchers learned that Nehhm was a variant spelling of the name Nihm, a regional and tribal name still attested today in Yemen, and spelled a variety of different ways, including Naham, Nahim, Nahm, Neham, Nehem, etc., with only the consonants N-H-M consistent.8 Such inconsistencies are a hallmark of attempts to transcribe Arabian names into the Latin alphabet,9 and a total of seventeen different variants of this name are attested.10 In most ancient Semitic languages, however, vowels go unwritten, and thus only the consonantal spelling NHM would have been on the plates.11 Thus, after considering possible linguistic factors, Semiticist Stephen D. Ricks — who literally wrote the dictionary on one of the major languages spoken anciently in Yemen — concluded: “Nahom as the realization of the southwest Arabian proper name nhm is eminently plausible.”12

The next step recommended by Christensen was to “search for the name on [additional] maps … even going back to medieval and ancient ones, if any can be found.”13 Several additional maps from the eighteenth and early nineteenth century attesting to this name, usually spelled Nehem, as well as several more contemporary government maps, where the spelling is frequently Naham or Nahm, have since been identified by Aston and others.14

For his final suggestion, Christensen wrote, “Still another step — when the political situation allows — would be archaeological fieldwork.”15 Yemen opened to archaeological fieldwork in the 1980s, and various excavations have been conducted by scholars from around the world since that time. As first noticed by S. Kent Brown, such fieldwork has recovered Ancient South Arabian inscriptions mentioning “Nihmites” (nhmyn) which confirm that the name went back to [Page 3]Lehi’s day.16 Fieldwork also uncovered extensive burial grounds in the surrounding area.17

Christensen also noted, “Nehhm is only a little south of the route drawn by the Hiltons.”18 Subsequent researchers identified ancient trade routes leading further south into Yemen and then swinging in a more easterly direction, consistent with Nephi’s directional statements (1 Nephi 16:13, 33; 17:1).19 It has also been confirmed that the only plausible candidates for Bountiful are located nearly due east of the Nihm region.20

As all these discoveries emerged, it generated a consensus among Latter-day Saint scholars and researchers identifying Nahom with the Nihm region of Yemen, with some coming to regard the complex relationship of all these interlocking details as a “convergence.”21 For example, Brant A. Gardner concluded, “This combination of a named location in the right place at the right time provides a less-than-coincidental convergence between the text and the appropriate real world setting.”22

Defining and Reexamining the Convergence

When discussing the relationship between archaeological discoveries and written sources, archaeologist William G. Dever explained that “convergences” are “points at which the two lines of evidence, when pursued independently and as objectively as possible, appear to point in the same direction and can be projected eventually to meet.”23 Therefore, if there really is a convergent relationship between Nahom and Nihm, it will be confirmed by independent examinations of both (1) where Nahom should be located, based on where the narrative details of 1 Nephi 16:33–17:1 best fit within Arabia; and (2) the historical geography of the Nihm tribe, seeking to understand its earliest known location and ancient boundaries, as best as can be determined from historical, archaeological, and scholarly sources. Only after the likely location(s) of both Nahom and Nihm have been independently assessed can they be compared — if they overlap, then it is fair to say that there is indeed a convergent relationship between the two, and “whenever the two sources or ‘witnesses’ happen to converge in their testimony,” according to Dever, “a historical ‘datum’ (or given) may be said to have been established beyond reasonable doubt.”24

In order to properly reexamine the “Nahom convergence” afresh, it will be necessary to revisit the details of Lehi’s journey as a whole, without assuming or taking for granted interpretations of the text that may be influenced by the presumed location of Nahom in Yemen. [Page 4]The past interpretations offered by Latter-day Saint scholars and researchers will not be ignored, of course, but emphasis will be placed on those interpretations that can be traced back to before the potential identification of Nahom with Nihm in 1977 or that can otherwise be shown to be formulated independently of any presumed association of Nahom and Nihm. These interpretations will then be considered against the data on ancient Arabia as reported by mainstream, non-Latter-day Saint scholars who are naturally uninfluenced by the details of the Book of Mormon narrative.

There will be four steps to this reexamination process: First, as mentioned, it will be necessary to look at Lehi’s journey as a whole — specifically looking at the details of Lehi’s route and the directions followed to get to and leave from Nahom, and then establishing where in Arabia such travel directions lead based on historically documented routes. This alone will considerably narrow the geographic window wherein Nahom should be found.

Second, the main detail in the text about Nahom is that it was the place where Ishmael was buried. Although we cannot determine with certainty that this was at a formal burial site, for various reasons (discussed below) it seems likely that Ishmael’s family would have preferred a more formal burial if such were available and accessible to them. As such, it is worth looking at the geographic distribution of burial sites and known necropolises within or near the region established by Lehi’s travel directions.

Third, 1 Nephi 16:33–39 will be reviewed for additional details that can potentially shed light on the location of Nahom, and these will be considered in the context of what is known about the general vicinity to which Lehi’s travel directions lead. All these factors combined may not necessarily pinpoint a single, specific spot, but they do provide a relatively clear view of the general locality wherein Nahom must be found.

Fourth, the historical geography of the Nihm region will then be independently considered based on scholarly interpretation of primary sources from Arabia. This location will be subsequently compared against the location established for Nahom, to determine if there is any overlap that thereby confirms a convergence. Then, in light of all the evidence reviewed throughout this paper, four potential scenarios will be considered for the specific location of Lehi’s basecamp established in 1 Nephi 16:33, the burial of Ishmael, and the subsequent turn eastward.

[Page 5]Lehi’s Route and the Frankincense Trail

To get to Nahom, Lehi first led his family from Jerusalem to “the borders near the shore of the Red Sea,” and then traveled another three days before establishing a camp in a valley near the coastline (1 Nephi 2:5–8).25 When they resumed their journey, they went in “nearly a south-southeast direction,” a bearing they generally maintained for the duration of “many days” until stopping just before Ishmael’s death (1 Nephi 16:13–17, 33–34). After Ishmael’s burial at Nahom, when the family resumed their journey, they “did travel nearly eastward from that time forth,” until arriving at a verdant coastal region they called “Bountiful” (1 Nephi 17:1–6).

Of course, determining every step and stop of Lehi’s route through Arabia with exacting precision is impossible to do, but this is to be expected from an ancient travel account — especially one written as a generalized summary decades after the fact (see 2 Nephi 5:28–34). As Daniel T. Potts has noted, when studying travel through Arabia in antiquity, “there are many well-known, logical routes, the existence of which can be demonstrated through time,” yet “it [is] nearly impossible to determine exactly which route was taken in an historical case, unless the itinerary is specified, and even then, the toponyms mentioned may no longer be identifiable.”26 In the specific historical case of Lehi’s journey, Nephi only provides a sparse and incomplete itinerary — mentioning only four camps (out of what must have been dozens) prior to the burial of Ishmael at Nahom, and afterwards only mentioning the final destination of their overland journey (see 1 Nephi 2:5–10; 16:6, 12–14, 17, 33–34; 17:5–6). Such sparse references to named locations is not uncommon in ancient Arabian travel accounts, and typically makes it difficult to determine the exact route followed in any given case.27 This difficulty is further compounded in Lehi’s case by the fact that, apart from Nahom, all the toponyms in Lehi’s itinerary are given to their various camps by Lehi or his family and are thus unidentifiable via outside historical records:28

- “And it came to pass that he called the name of the river Laman” (1 Nephi 2:8)

- “my father dwelt in a tent in the valley which he called Lemuel” (1 Nephi 16:6)

- “and we did call the name of the place Shazer” (1 Nephi 16:13)

- “Ishmael died and was buried in the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:34)

- [Page 6]“And we did come to the land which we called Bountiful” (1 Nephi 17:5)

- “And we beheld the sea, which we called Irreantum” (1 Nephi 17:5)

- “And we called the place Bountiful because of its much fruit” (1 Nephi 17:6)

Despite this limitation, the first two camps can be identified with a reasonably high degree of confidence, thanks to Nephi’s specific statements on the number of days traveled to reach each destination. First, nearly all researchers agree that the Valley of Lemuel (see 1 Nephi 2:5–10) is located in Wadi Tayyib al-Ism, approximately 74 miles of travel south of Aqaba.29 Similarly, there is a general consensus identifying the next camp, called Shazer (see 1 Nephi 16:12–14), with Wadi Agharr (also known as Wadi Sharma), which lies approximately 70 miles of travel southeast of Wadi Tayyib al-Ism.30 Whether or not these exact identifications are correct, however, the specification of exactly seven days total for the trek from Aqaba to Shazer (1 Nephi 2:5; 16:13) guarantees that Lehi’s location by this point in his journey could not have been too far from the general vicinity of Wadi Agharr.31

From here, Nephi only specifies that the party traveled “many days” before reaching the next, unnamed camp mentioned in his account, and then they continued on once again for “many days” before arriving at another unnamed location, after which they buried Ishmael at Nahom (1 Nephi 16:15–17, 33–34). Unsurprisingly, this indefinite itinerary makes “it nearly impossible to determine exactly which route was taken”32 from Shazer to Nahom, just as is the case with many other accounts of trans-Arabian travel. Despite this inability to pin down Lehi’s exact route, Latter-day Saint researchers have long recognized that the fabled “incense road” or “frankincense trail” demonstrates the existence of well-known, logical routes that mirror the general course taken by Lehi and his family as outlined in 1 Nephi.

The Frankincense Trail in the Early First Millennium bc

The main course of the Frankincense Trail transported incense from Dhofar and Hadramawt westward through the South Arabian “caravan kingdoms,” and then north-to-northwest through western Arabia (see Map 1).33 In 1957, Hugh Nibley was the first to point out that this route mirrored Lehi’s trail, at least in its general course: “For many centuries the richest trade route in the world was that which ran along the eastern shore of the Red Sea for almost the entire length of the Arabian peninsula. [Page 7] This is the route that Lehi took when he escaped from Jerusalem.”34 Nearly 20 years later, when the Hiltons were commissioned to retrace Lehi’s steps, they used the Frankincense Trail as their template, arguing that Lehi’s family would have stuck to this well-known route with access to water and other key resources.35 Since then, most researchers have agreed that Lehi likely followed this major trade route for at least parts — and perhaps even the majority — of his journey, with George Potter and Richard Wellington developing the most comprehensive argument for placing Lehi on the Frankincense Trail.36

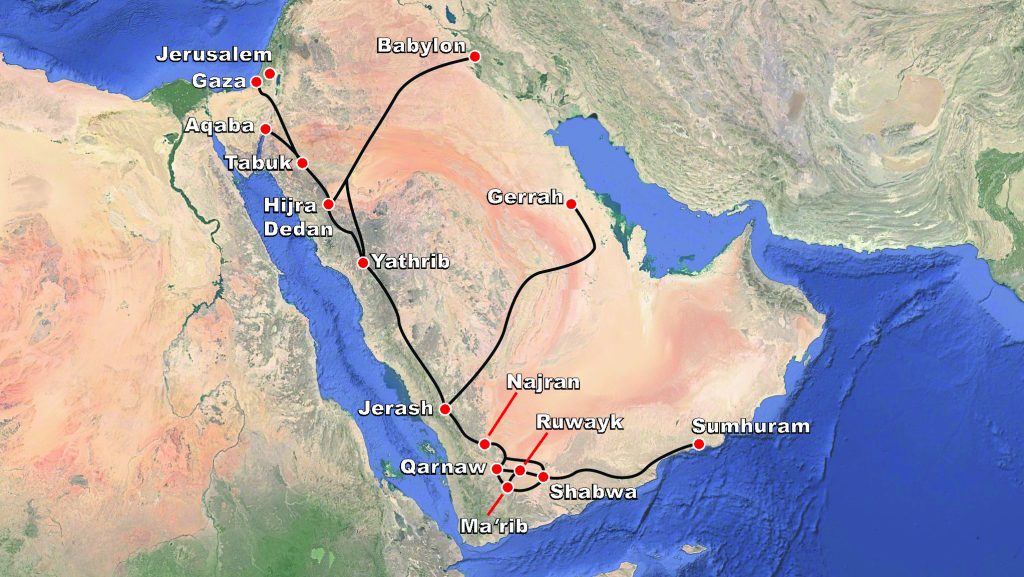

Map 1. The Main Overland Routes of the Frankincense Trail.

The most detailed information on the incense trade and the roads it used comes from Greco-Roman and other classical era sources that post-date Lehi’s time by hundreds of years.37 Nonetheless, numerous sources confirm that this trade was well underway in Lehi’s day.38 The origins of the South Arabian incense trade with Mesopotamia and the Levant began sometime between the thirteenth and the eighth centuries bc.39 Assyrian records attest to trade and other interactions with Sabaeans by the mid-eighth century bc, with some indications suggesting such trade was already in place by the early ninth century bc.40 More recently, an inscription discovered in Jerusalem, potentially referring to incense and written in Ancient South Arabian, dates to the tenth century bc.41 If this is accurate, it brings the evidence to within King Solomon’s era, giving historical credence to his reported visit from the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10:1–13) and suggesting that Israel was already involved in trade [Page 8]with South Arabia by the beginning of the first millennium bc.42 Various additional biblical texts and archaeological finds clearly establish contact between Judah and South Arabia by the seventh (and likely the eighth) century bc.43

While the most detailed information is from later periods, a generalized outline of the main trade routes can be recovered from early-to-mid first millennium bc sources that are closer to Lehi’s time. One recently discovered bronze inscription written in Sabaic, dated by many scholars to ca. 600–550 bc, narrates the military and commercial travels of a man named Ṣabaḥuhumu (ṣbḥhmw) from Nashq (ns2qyn), one of the Wadi Jawf city-states.44 Under the auspices of the Sabaeans, Ṣabaḥuhumu “traded and led a caravan to Dedan and Gaza and the towns of Judah.”45 Not only does this confirm that there was contact between Judah and Saba at this time, it also indicates that the south-to-north trade route linking them began in the Wadi Jawf (Nashq) and passed through Dedan.46 As Alessandra Avanzini concluded, in the early first millennium bc, “Sabaʾ must have controlled … a commercial path along the Red Sea towards Palestine and the Mediterranean.”47 A fifth century bc Minaic wall inscription from Barāqish, another city-state in the Jawf, talks about caravaneers traveling “on the route between Maʿīn and Rajma.”48 Rajma (rgmtm) refers to Najran, another major stop along the north-south trade route, and according to Avanzini, this text indicated that the Minaeans had wrested control of the “caravan route along the Ḥijāz” from the Sabaeans by the end of the fifth century bc.49

Thus, in the early-to-mid first millennium bc the south-to-north route of the incense trade evidently began in the Wadi Jawf, passed through Najran and Dedan, and then continued on to places in Judah and along the Mediterranean coast — the same basic route documented in greater detail in later times.50 Biblical texts also link Dedan, Sheba (Saba), and Raamah (Rajma/Najran) in a way that suggests Israelites of the seventh–sixth centuries bc had a clear knowledge of this important trade route (see Genesis 10:6; Ezekiel 27:21–22).51

Inscriptional evidence also indicates that the Wadi Jawf was the nexus of the north-south trail and the roads bringing incense from the east during the early first millennium bc. Key evidence comes from the city of Haram, located in the Jawf, where an early seventh century bc inscription was found which invokes the god of Najran (ʿṯtr ḏ-rgmt).52 This most likely means that Haram and Najran had commercial ties,53 linking Haram to the northward trade route discussed above. Two other inscriptions from Haram, also dated to the early seventh century bc, [Page 9]identify leaders of Haramite trading outposts established in areas to the east of the Jawf — the “chief of ʿArarāt” (kbr ʿrrt), identified as al-Asaḥil, northwest of Marib, and the “chief of the Ḥaḍramawt” (kbr ḥḍrmwt), the easternmost tribal kingdom of South Arabia.54

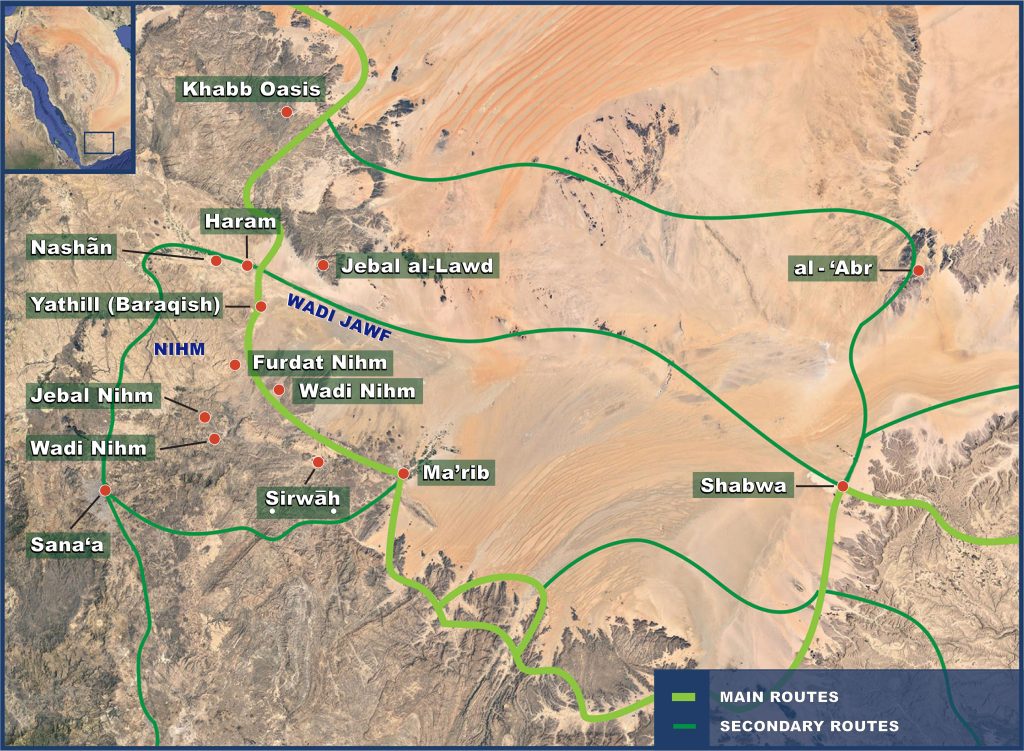

Thus, Haram was evidently the turning point within a trading network that expanded northward and eastward from the Jawf, going from Hadramawt in the east, to ʿArarāt, and then Haram, from whence it turned north toward Najran. While this does not allow us to reconstruct the exact route eastward used by the Haramite traders, as with the north-to-south trail discussed above, this is generally consistent with the east-to-west roads used in the incense trade, as documented in later sources (see Map 2).55

Map 2. Main Trade Routes in South Arabia.

This overall consistency hardly comes as a surprise, given the “geographical determinism” that dictated travel in the ancient Near East, and Arabia in particular. As Barry J. Beitzel explains it, “there were certain largely unchanging physiographic and/or hydrologic factors which determined … that routes followed by caravans, migrants, or armies remained relatively unaltered throughout extended periods of time.”56 Because of this, according to Michael C. Astour, “It is thus possible, when at least some of the transit points can be located on the map, to restore the [Page 10]entire route by using the data of physical geography and of more-detailed itineraries from a later age.”57 Speaking specifically of South Arabia, Richard L. Bowen noted “that the country is geographically rugged and climatic conditions have not changed much in several thousand years,” and thus the same “routes have probably been in use for millennia.”58 Potts similarly observed, “The basic topography and hydrology of Arabia has not changed significantly in the last two to three thousand years,” and thus later travel reports — ranging from early Islamic pilgrimage roads to accounts of travel by camel in early modern times — “provide invaluable information on non-motorized travel possibilities in Arabia … in all periods” when properly “intergrat[ed] … with more ancient historical accounts.”59

With this in mind, we can plausibly use the later reconstructions of the Frankincense Trail — and the local road networks it intersected with — to flesh out the basic overall route that can be confirmed by early-to-mid first millennium bc sources. Even if some specific routes did not come into common use until later periods, the general stability of the terrain, hydrology, and climate over time suggest most were possible to use by earlier travelers, and likely were used at least occasionally by some prior to the time when they were more widely documented.

Lehi’s Connecting Route to the Frankincense Trail

The Frankincense Trail provides a well-known, logical route which existed in the early first millennium bc that broadly mirrors Lehi’s route, and most Latter-day Saint scholars (beginning with Hugh Nibley in 1957) agree that Lehi likely followed this trail for at least part of his journey. To get to the main route of the incense road from the area of Wadi Agharr/Sharma (the likely location of Shazer), sooner or later Lehi would have needed to take a connecting pass through the Hijaz or Asir mountains. Once again, there are a number of logical, historically documented routes that Lehi potentially could have taken.60

Perhaps the most direct option would be to follow Wadi Sharma itself, which Aston notes “provides a pathway further into the interior of Arabia.”61 If the Roman port Leuke Kome was located at Wadi Ainounah, as many scholars believe, then there may have been a route going straight through Wadi Sharma and onto Tabuk — a stop along the main incense road — at least during the Roman period.62 However, such a path — nearly due east for approximately 85 miles — does not fit well with the directions provided by Nephi for this part of his journey.63

[Page 11]A more likely route is the early Islamic pilgrimage road that went from the Gulf of Aqaba to Medina, passing right through Wadi Agharr and continuing to al-Ula (the location of ancient Dedan), where it merged with the main incense trail.64 Nigel Groom suggests that this route was used as a secondary trail in the incense trade, based on references from Greco-Roman sources and archaeological evidence near Aqaba dated to the sixth century bc.65 Connecting to the fertile areas of the Hijaz mountains in a generally southeastward direction, this trail fits well with Nephi’s account, as Potter and Wellington have argued.66

Alternatively, Lehi’s party could have gone down the coastline another 150 miles to al-Wajh, passing through oases such as Wadi al-Muweileh and Wadi al-Aznam.67 From al-Wajh, they could go southeast to the mouth of Wadi Hamd — a broad, fertile valley that provides natural passage into the mountains southeastward to Medina.68 In pre-Islamic times, Medina was known as Yathrib and is attested as a stop along the main trade route in Babylonian sources from the sixth century bc.69 If Leuke Kome was alternatively located in al-Wajh (or the nearby Ras Karkuma), as favored by some scholars, then Wadi Hamd was almost certainly used as the main route connecting the port to the caravan trails inland.70 Thus, taking this generally south-southeastward route from Wadi Agharr to Medina would also be largely consistent with Nephi’s account.

Several additional wadi networks also provide passage through the northern Hijaz, and other passes exist further to the south, such as the routes linking Mecca to the Frankincense Trail.71 Further south still is the road leading southeastward from al-Qunfudah to Najran that the Hiltons proposed as part of Lehi’s route.72 No doubt several more possible passes could be proposed. It is impossible to determine with certainty which route was followed, but three clues suggest that they went into the mountains soon after departing from Shazer: (1) the Red Sea and its “borders” quickly drop from the narrative; (2) they were hunting and “slaying food by the way,” and (3) traversing through “fertile parts of the wilderness” (1 Nephi 16:14–17). All these details are consistent with moving away from the coast and crossing the northern Hijaz, where there is greater fertility and hunting grounds in the mountains and the inland plateau than along the coast.73

In any case, all of these demonstrate the existence of well-known, logical routes that generally maintain a south-to-southeastward course and could have been taken by Lehi to cross the mountains and merge onto the main route of the Frankincense Trail somewhere between [Page 12]Dedan and Najran. From there, they naturally would have continued on, “following the same direction” further south-southeast into Arabia, “traveling nearly the same course as in the beginning” until Ishmael’s passing (1 Nephi 16:14, 33–34).

Lehi’s “Nearly Eastward” Trek: Possible Turning Points

After Ishmael’s burial at Nahom, Lehi’s party turned “nearly eastward from that time forth” (1 Nephi 17:1). Using the known points where ancient trade routes turned to a generally east-west directional bearing provides a limited number of places where Lehi and his family could have turned “nearly eastward” for the final leg of their journey. This, in turn, puts constraints on where Nahom must be located, independent of any historical or inscriptional evidence for where a tribe or toponym with an NHM name might be found. As the Hiltons reasoned in 1976, “the locale of Nahom would be in the area where the frankincense trail is known to have turned eastward. Thus, we determined that a study of the communities in this area might uncover a possible Nahom.”74

Historically, there are three main routes known to connect the Jawf region of Yemen to the Hadramawt in the east (see Map 2). The southernmost route — which most scholars presume was the primary road used by the incense caravans — departed from the Wadi Jawf at Barāqish (known anciently as Yathill) southward for roughly 10–15 miles before bending eastward toward Marib. It was then possible to cut northeastward to Ruwayk (see Map 1, following Loreto), thereby merging with the route coming directly out of the Jawf (discussed below).75 The main trail, however, took a more circuitous route eastward from Marib, as it skirted the edges of the mountains first in a southeastward, then a northeastward direction, “leading one through settlements in an eastward arc from Marib to Shabwah.”76 Despite the fact that it was the least direct route eastward, the main trail had the greatest access to water, food, and other resources, and hence S. Kent Brown argued that Lehi most likely stuck to this road, reasoning that “it was more prudent for them to follow the [main] incense trail as long as they could.”77

More directly eastward was the route that departed out of the Wadi Jawf and cut across the desert along a narrow gravel corridor in a generally east-southeast direction toward Shabwa.78 Because this route lacked regular access to water, most scholars presume that it was a rarely used short-cut followed mainly by lightly loaded caravans and smaller groups (such as Lehi’s family would have been).79 A. F. L. Beeston, however, believed it was actually the primary route of the incense trade.80 Also [Page 13]according to Beeston, the armies of Saba and Hadramawt — and on one occasion, he argued, the Romans — used this corridor to launch military campaigns against one another, traveling directly east-west between the Jawf and the wells of al-ʿAbr.81 Thus, Ṣabaḥuhumu probably followed this route when he marched “with the army of Sabaʾ into the land of Ḥaḍramawt,”82 indicating the likely use of this eastward road close to Lehi’s day.83 Both Warren Aston and co-authors George Potter and Richard Wellington independently proposed variations on Lehi’s trail which incorporate routes running through this eastward corridor.84

The final east-west route bypassed the Wadi Jawf altogether, skirting along the southern edge of the Empty Quarter to the well of Mushayniqah and then to al-ʿAbr and on to Shabwa or elsewhere within Wadi Hadramawt. Like the route through the Jawf, this trail is generally presumed to have been used by smaller, lightly loaded caravans due to its difficulty and limited access to water and other resources. Nonetheless, inscriptional graffiti attests to its use in antiquity.85 Before Nahom was thought to correlate with the Nihm region, the Hiltons suggested that this was the route the Lehites followed, stating, “The shorter but more difficult part of the frankincense trail that Lehi and his party took in turning eastward skirted the very fringe of the largest sand desert on earth.”86

While the exact itineraries of each eastward route could vary depending on different factors and circumstances, these represent the only three junctures where well-known ancient routes go in a primarily east-west direction across the Arabian Peninsula. While there were routes north of Najran that led across to the eastern side of the peninsula — namely the road to Gerrha, and the North Arabian trails to Mesopotamia — these all run in a decisively northeastward direction (see Map 1).87 It is hard to imagine a southbound traveler along the incense trail from Palestine switching over onto any of these northeast-trending trails and describing their new course as “nearly eastward.”88

Truly, as Brown previously observed, it is only “after passing south of Najran … [that] both the main trail and several shortcuts turned eastward” and this “is the only place along the incense trail where traffic ran east-west.”89 Unsurprisingly, considering the “geographical determinism” already discussed, there are environmental factors that dictate this course, as Aston noted:

Only recently has satellite-assisted mapping enabled us to appreciate that after traveling southward into Arabia, as the Lehites did, people are prevented from easterly travel by the [Page 14]shifting, waterless dunes of the vast Empty Quarter, as much today as in the past. However, a narrow band of flat plateaus … marking the southern end of the Empty Quarter, presents the first opportunity for travel in an easterly direction.90

Furthermore, the text does not merely require that it be possible to turn eastward but that Lehi and his family be able to continue eastward to a fertile coastal location that fits Nephi’s description of Bountiful (1 Nephi 17:5–6). Since the 1950s, scholars have generally agreed that the only place along the entire southeastern coast of Arabia that matches Nephi’s description is the Dhofar region in southern Oman.91 The exact east-west relationship of Nahom and Bountiful depends to some extent on which specific turning point is used and where in Dhofar Lehi specifically camped (as discussed below), but generally speaking Dhofar is basically eastward from the Wadi Jawf and its surrounding region. Thus, for our purposes, it is sufficient to note that each of these eastward routes converge around either al-ʿAbr or Shabwa, and from there various overland routes could be followed further eastward to Dhofar.92

For all practical purposes, Lehi’s turn eastward must have taken place within this limited range — approximately 60-miles in length, north to south — positioned around the Wadi Jawf, regardless of whether or not a place or tribe called NHM could be documented within or near that zone.

Ishmael’s Burial within Ancient Yemen’s Funerary Landscape

Nephi’s succinct statement, “And it came to pass that Ishmael died and was buried in the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:34) can be interpreted in two ways: (1) that Ishmael both died and was buried at Nahom, or (2) that Ishmael died while they were camped at an unnamed location (see v. 33) and was then taken to Nahom for burial. Aston has argued it this way:

It is important to note that Nephi does not state that Ishmael died at Nahom, but that he was buried there. While it remains possible, it is unlikely that Ishmael conveniently died right at a place of burial. Despite the need in a hot climate to bury the deceased quickly, Ishmael’s body may have been carried by the Lehite group for some distance, perhaps for days, in order to provide him a proper burial.93

It must be understood that burial of the dead was of grave importance in the biblical world, and lack of proper burial was considered a disgrace.94 [Page 15]In the Bible, according to Elizabeth Bloch-Smith, “interment was accorded to all who served Yahweh; sinners were cursed with denial of burial or exhumation.”95

For an Israelite, burial preferably occurred in the land of Israel in a family tomb where one’s ancestors were buried. As Rachel S. Hallote explains, “A person who was gathered to his ancestors and buried in a family tomb would not be lost [or forgotten]. … Burial in a family tomb associated an individual with the greatness of his ancestors who were also buried there.”96 The patriarchs Jacob and Joseph insisted they were not to be permanently interred in Egypt but that their remains were to be taken back to the land of Israel and buried with their fathers (Genesis 47:29–31; 49:29–33; cf. 50:24–26). Some Jews of the diaspora returned to Judea to inter the remains of their deceased loved ones — as attested to by sarcophagi of Yemeni Jews from the third century ad found in the Jezreel Valley.97 Martin Gilbert explains, “Yemeni Jews made great efforts to return to Judaea when burying their dead, sometimes embarking on a journey across the deserts of Arabia that would take at least sixty days by caravan.”98 This puts a new perspective on the daughters of Ishmael’s bitter lament that Lehi “had brought them out of the land of Jerusalem, saying: Our father is dead” (1 Nephi 16:35). This was not merely a yearning for the comforts of home, but a desire to bury their father in their homeland with his ancestors. No matter how “desirous to return again to Jerusalem” they may have been (1 Nephi 16:36), however, this was not a viable option for the families of Lehi and Ishmael.

Absent the opportunity to bury Ishmael in their homeland, it is certainly possible that he was simply buried along the roadside near where he died, as was apparently done on other occasions (see, e.g., Genesis 25:8; 35:18–20; Numbers 20:1).99 Yet for several reasons, this would have been considered suboptimal. Formal burial grounds could include a ceremonial center or shrine (cf. the “house of mourning,” byt mrzḥ, in Jeremiah 16:5) that could be used for the proper performance of funerary rites.100 It would also have the added benefit of ensuring the grave is occasionally visited by others, something that was believed to actually benefit and provide care for the deceased in the afterlife.101 Ishmael’s family no doubt lamented that they must bury their father in a strange land to which they will never be able to return to commemorate and care for him, but if he was buried near other tombs, then at least others may visit and commemorate him as an “adopted ancestor,”102 a possibility that could have brought some comfort to the grieving travelers.

[Page 16]Ultimately, according to Bloch-Smith, “Proper burial required interment in a qeber (Gen. 23.4; Exod. 14.11; Isa. 22.16) or qeburâh (Genesis 35.20; Deuteronomy 34.6; Isa. 14.20), ‘a burial place’.”103 John A. Tvedtnes pointed out that the Hebrew word typically meaning “place” (mqwm) is at times used to mean the grave, tombs, or the “destination of the dead.”104 Thus, when Nephi says Ishmael “was buried in the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:34), he may be conveying the fact that this was a place with a formal mortuary complex — a “destination of the dead” of sorts. As early as 1950, Hugh Nibley proposed that Nahom was not simply where Ishmael happened to die, but rather was “a desert burial ground,” noting that “though Bedouins sometimes bury the dead where they die, many carry the remains great distances to bury them.”105 Therefore, the location of appropriate burial grounds is another consideration for the location of Nahom that can be assessed independent of the historical or geographic evidence regarding the Nihm tribal territory.

Turret Tomb Necropolises

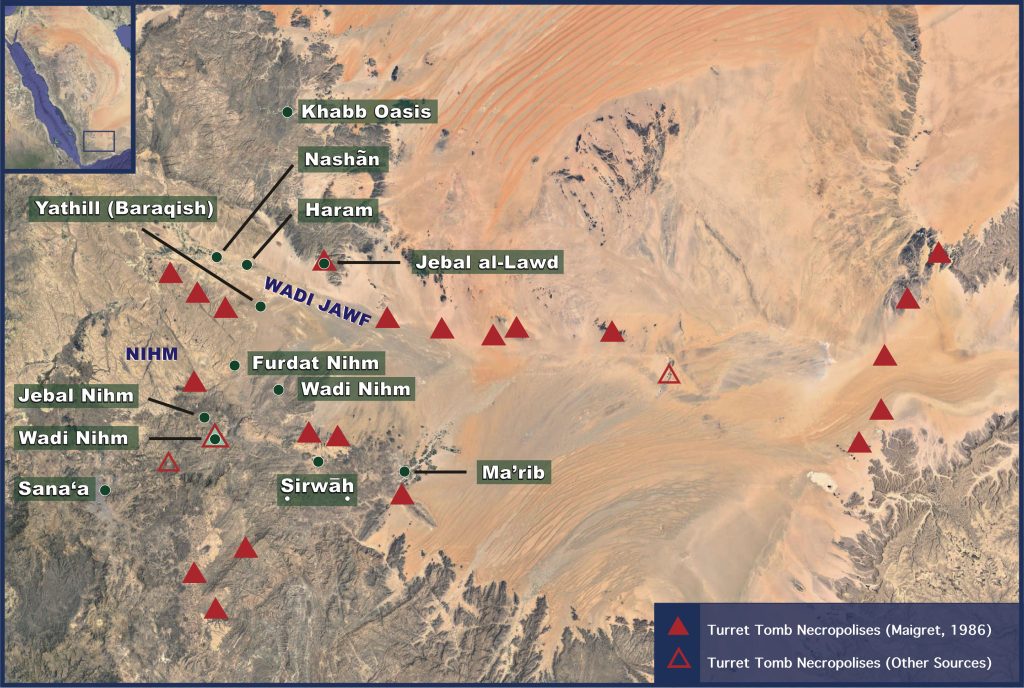

To this day, the desert landscape of northern Yemen is dotted with extensive, ancient burial grounds. As Jean-François Breton has noted, “tombs have been found in fairly dense concentrations throughout the [Yemeni] countryside.”106 Aston has long drawn attention to the large ancient necropolises at Ruwayk and Jidran,107 where thousands of above-ground cairns, or “turret tombs,” stretch across the outlying desert east of the Wadi Jawf.108 Alternatively, when Brown visited Yemen to film the documentary Journey of Faith, Yemeni archaeologist Abdu Othman Ghaleb took him to an ancient cemetery “with thousands of burials at the eastern end of Wadi Nihm where it turns north and runs toward Wadi Jawf.”109 In addition to these, there are several other places of burial within or near the “eastward turn zone” defined above.

According to Alessandro de Maigret, there are also “huge necropolises” of circular cairns “in the mountains on the borders of the Jawf valley.”110 Starting west of Barāqish, on the slopes of Jebal Yām, these tombs “continue almost uninterruptedly as far as Jabal Silyām,” as documented by Angela Luppino.111 Turret tombs were also found to the north, on Jebal al-Lawd, which lies on the northeastern edge of the Wadi Jawf.112 Further south, turret tombs were found near the village of Milḥ.113 Italian archaeologists have documented and mapped the distribution of these and other turret tomb necropolises that are spread across the Yemeni landscape (see Map 3).114

[Page 17]

Map 3. Turret Tomb Necropolises in Northern Yemen.

Based on current evidence, most of these turret tombs were built in the early 3rd millennium bc,115 but many were either built or reused in the first millennium bc and even into the early centuries ad.116 Human remains recovered in the cairns just north of Ṣirwāḥ, for example, were radiocarbon dated to between the eighth century bc to the first century ad, and the tombs along the southern edge of the Jawf are also believed to have been in use during this same time-period.117

Since these tombs are typically found in isolated regions of the desert, far away from any major ancient settlements, they are generally believed to have served remote “outsider” populations, such as nomads, foreigners, and travelers connected with the caravan trade.118 They may have been connected to the “Arabs,” which were a distinct ethnic group in antiquity that lived on the periphery of South Arabian society (more on this below).119 Imported items from as far away as Iran recovered from some of these tombs “seems to point to a certain ‘internationality’ of the people who buried their dead in these towers,” and other evidence indicates “the deceased had to be preserved during long journeys before reaching the designated tomb.”120

Thus, these burial grounds with turret tombs were in active use when Lehi’s family would have arrived in South Arabia, and in some cases may have been used by long-distance, foreign/international travelers.

[Page 18]The Eastward Trails and the Distribution of Turret Tombs

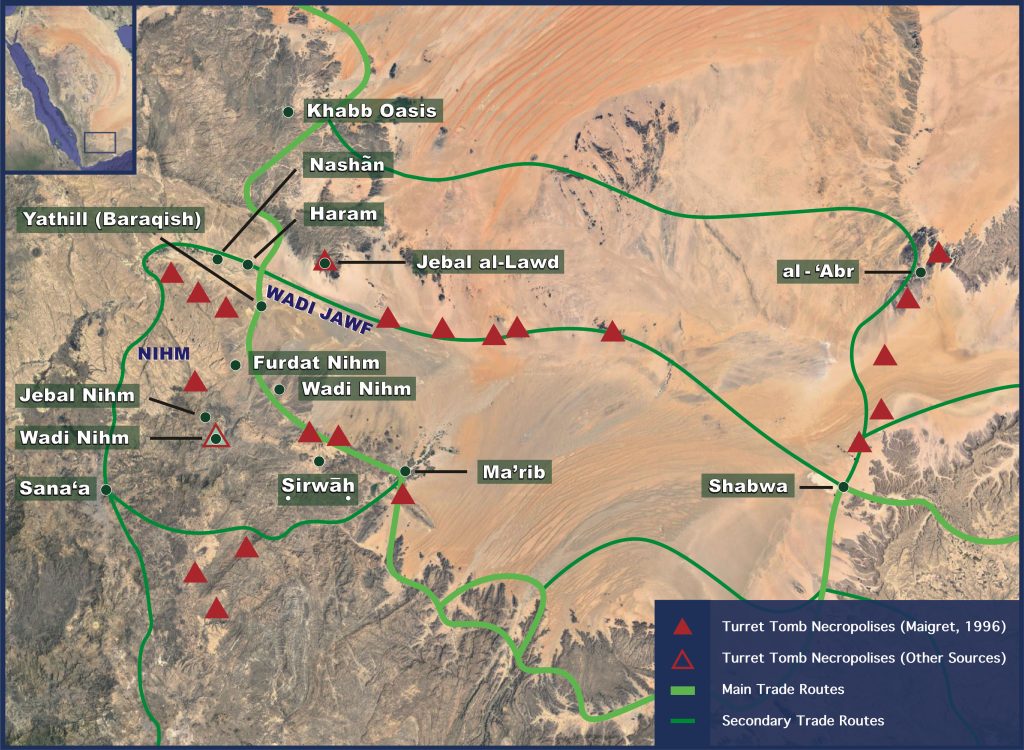

One of the major reasons why these tombs are thought to be connected to transient populations is because, according to de Maigret, “their particular distributive pattern seems to suggest that there was a link between these structures and the ancient trade routes.”121 Burkhard Vogt further explained, “Since these [tombs] align with trade routes it has been proposed that they represent people who were also in charge of the caravan trade in frankincense, aromatics and other commodities.”122 In fact, archaeologists have “found traces of the ancient roads, which are otherwise unrecognisable” by “following the lines of the turret tombs.”123 Thus, according de Maigret, “the turret tombs … can be used as precious indicators in a reconstruction of the ancient itineraries.”124

Potentially reconstructing Lehi’s ancient itinerary from Nahom using a trail of tombs certainly feels apropos, since his stay in this region involved the burial of the dead. Interestingly, the most striking correlation between tombs and trail is the “continuum of funerary complexes” that stretches out in a “nearly eastward” direction, from “the Jawf, [to] Jabal Jidran, Jabal Ruwaik, ath-Thanīyah, [and] al-ʿAbr,” continuing into the Hadramawt “until east of Tarīm.”125 According to Breton, this chain of burial complexes corresponds with the eastward caravan trail: “A map of these sites shows how they run along the principal routes eastward from ʿIrma to Shabwa to Barâqish to upper Jawf …. There is a clear connection between the geographical distribution of these burial sites and the caravans that followed these routes.”126 This is dramatically confirmed when the geographic distribution of the tombs is overlaid onto the map of eastward trails (see Map 4).

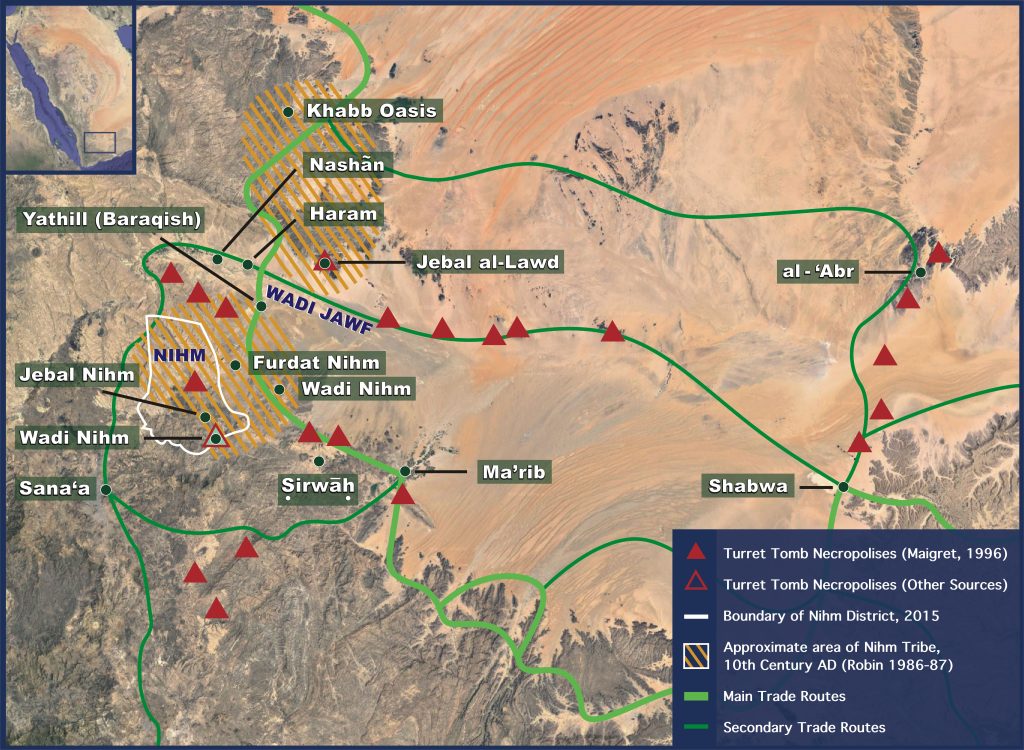

Map 4. South Arabian Trade Routes with Turret Tombs.

This convergent relationship between burial of the dead and eastward travel in ancient Yemen is certainly interesting when compared with Nephi’s account of burying Ishmael at Nahom and then turning “nearly eastward” (1 Nephi 16:34; 17:1). This is consistent with Nahom being somewhere in or near the general vicinity of the Wadi Jawf, as concluded from the evidence of the known eastward turning points.

Carved Face Funerary Stelae

Further indication that this was an appropriate region for travelers to bury or commemorate their dead comes from the large corpus of about 640 funerary stelae recovered from the Wadi Jawf region.127 These mortuary stelae are generally made out of sand- or limestone, are rectangular in shape, and have facial features carved (often crudely) into them with the name of the deceased individual usually inscribed [Page 19]beneath the face.128 The exact origins of the population these monuments represent is still a subject of some debate, but scholars generally agree that the use of cheap materials and low-quality craftsmanship indicate that these were people with little means or limited access to resources.129 Most also agree that at least some of the individuals commemorated by these stelae were foreigners, travelers, or otherwise outsiders among the Jawf population.130

Christian Robin and Sabina Antonini have each suggested that these stelae attest to the presence of ethnic “Arabs” from the mountains north of Wadi Jawf living among Jawf populations in the early first millennium bc.131 Several other scholars have noted ties with North Arabian cultures.132 Some evidence even suggests that some of these stelae represent people who came from beyond the Arabian cultural sphere. For instance, according to Mounir Arbach and Jérémie Schiettecatte, one represented a woman of Babylonian origin.133 A study of the onomastics of those stelae found in situ at Barāqish found links to Northwest Semitic and Akkadian, in addition to ties with North Arabian names.134 Thus, some of the people memorialized by these stelae may have been from far off places in North Arabia, Mesopotamia, and the Levant.

[Page 20]Overall, this evidence suggests that these stelae represented a combination of both locals and foreigners who were involved in long distance travel; not necessarily wealthy merchants and traders, but “the caravaneers themselves … the people who materially transported the merchandise up and down the Peninsula, on behalf of princes, priests or traders who lived in the cities,” perhaps including ethnic “Arabs” who lived on the northern fringes of South Arabian society.135 This is all the more likely in light of evidence from the archaeological context at Barāqish suggesting that some of these stelae were used as cenotaphs — monuments commemorating persons who died and were buried somewhere else.136 If this is correct, then it would imply that the Jawf was a central location where some who traveled long distances on the caravan trails commemorated their dead, even if they had died somewhere else and their bodies could not be brought for burial.

This large corpus of funerary stelae thus provides further evidence that the region around the Jawf was an appropriate place for travelers such as Lehi and his family to bury, or at least memorialize, their deceased companion, Ishmael (1 Nephi 16:34). In fact, one of these funerary monuments (Figure 1), dated to around the sixth century bc, is inscribed with the South Arabian form of the name “Ishmael” (ys1mʿʾl).137 Based on the broader context drawn from the overall corpus of carved face stelae, it is possible this Ishmael was a foreigner who traveled along the caravan trails and had ties to the Arab tribes north of the Jawf. This could fit, in very broad strokes at least, with the general profile of Ishmael in the Book of Mormon, but it is impossible to come to even a tentative conclusion as to whether he is the “Ishmael” of this stela.138 Nonetheless, given its dating and overall context, this possibility should not be ruled out.

Figure 1. Carved face funerary stela with the name YS1MʿʾL (Ishmael) on it. (Used with permission of Mounir Arbach.)

Other Textual Clues in 1 Nephi 16:33–39

The clearest and strongest indication of Nahom’s location is the directional shift “nearly eastward,” and the second most significant clue is its use as a place of burial. Yet other details in the narrative of 1 Nephi 16:33–39 also need to be taken into consideration when trying to determine the setting for these events. Unfortunately, this terse account does not yield as much clear information as one might hope; nonetheless, probing the full narrative may provide hints or clues that can help further triangulate where we should be looking.

First, Nephi says that after an extended journey of “many days” they once again established camp so they could “tarry for the space of a time” [Page 21](1 Nephi 16:33). The next thing reported in the text is Ishmael’s death and burial at Nahom (v. 34). As already noted, it is possible the family carried Ishmael’s body to an appropriate burial ground, and so it is unclear whether they were already at Nahom or if this is a separate location unnamed in the narrative. Yet in ancient Israel, according to R. Dennis Cole, “People were buried as soon as possible after death.”139 Roland de Vaux explained that the exact “interval which elapsed between death and burial” is not known with certainty, but “the delay was probably very short … it is probable that, as a general rule, burial took place on the day of death.”140 Extenuating circumstances — such as passing away in a remote area far from any proper places of burial — may have justified postponing the burial by a day or two, but Ishmael’s family was still undoubtedly eager to bury their deceased patriarch with as little delay as possible. Thus, they were almost certainly near Nahom, if not already within its boundaries, by the time they stopped and set up camp.

[Page 22]In order for Lehi’s group to “tarry for the space of a time,” there had to be access to needed resources — at the very least water, and perhaps food and other provisions as well. Warren Aston reasons, “This wording makes it certain that they were in a place where they could rest and obtain food,” and speculates that they harvested crops and their women gave birth during this period of respite.141 He thus suggests that they had already arrived in the fertile and populated Wadi Jawf by this point.142

On the other hand, upon their father’s passing, the daughters of Ishmael lamented “we have suffered much affliction in the wilderness, hunger, thirst, and fatigue” (1 Nephi 16:35). Laman and Lemuel also complain of Nephi’s deceiving them by “cunning arts,” and leading them in “some strange wilderness” with the intent to make himself “a king and a ruler over us” (1 Nephi 16:38). From a narratological perspective, these complaints appear to allude back to their previous camp, where Nephi’s bow broke, the family suffered from hunger and fatigue, and Nephi made himself a new bow — a symbol of kingship in the ancient Near East — and used the Liahona to guide him to where he should obtain food (1 Nephi 16:17–32).143 Yet some researchers have also suggested that these complaints may reflect the experiences of the family on their journey between the broken bow camp and Nahom.144

There is generally little fertility in the vast desert-mountain region between Najran and the Jawf. Travelers have little choice but to skirt along the edge of the rocky hills on the west and the sand dunes of the Empty Quarter on the east, or try their luck in the winding maze of twisting wadis still used as camel trails in fairly recent times.145 Nineteenth century Jewish-French explorer and Semitist Joseph Halévy got lost and “wandered, hungry and thirsty” in this region after being abandoned by his local guides.146 The stretch between Bishah and Najran, where the broken bow camp was most likely located, is equally unforgiving.147 With few opportunities to rest and restock on food and water supplies, Lehi’s family well could have “suffered much hunger, thirst, and fatigue” during this challenging stretch of their journey, and the large sand dunes of the Empty Quarter would have been a new — and perhaps “strange” — kind of wilderness to the people in Lehi’s party.

Even after arriving at Nahom, the daughters of Ishmael evidently still feared that they would “perish in the wilderness with hunger” and it was only through the Lord’s blessing that they obtained “food that we did not perish” (1 Nephi 16:35, 39). If they were in a populated, fertile area (such as the Wadi Jawf), it is possible they had to wait for a crop harvest or that they lacked provisions to trade for food, and so perishing [Page 23]for want of food remained a concern.148 In the midst of the daughters’ grieving over the loss of their father, it is also likely that other risks and fears became magnified. As Aston reasoned, “in the bitterness of their grief they saw only the prospect of more hardship and hunger in the future under Lehi’s leadership” and “they knew their present stop was only temporary and not their final destination.”149 Thus, Aston concludes, “Concern over the immediate lack of food, and fear that only more of the same lay ahead, seems to be at the heart of their complaint.”150 In addition, their complaint could reflect exaggerated frustration that their limited food resources prevented them from hosting a marzeaḥ — a feast that was a customary part of Judahite mourning rituals of their time, and intended to “comfort” (nḥm) and provide “consolation” (tnḥmṯ) to the bereaved (see Jeremiah 16:5–9).151

In contrast, Potter and Wellington argue that the party’s risk of perishing at Nahom was real, and thus it could not have been a populated, fertile place. Instead, they argue that Ishmael’s health forced Lehi’s family to stop for an extended period in a less-than-ideal location, where they had access to water but not food or other needed resources.152 Thus, Potter and Wellington argued that the events of 1 Nephi 16:33– 39 occurred before Lehi and his family reached the Wadi Jawf, “most probably somewhere in the 50 miles north of jabal al-Lawdh … and south of wadi Khabb.”153

These contrasting interpretations of 1 Nephi 16:33–39 yield slightly different conclusions about the location of Nahom, both of which fall within the boundaries of the eastward turn zone within which Nahom must be located. In either case, the implication from the text is that the journey prior to their arrival at Nahom passed through a barren, waterless region which forced the group to endure greater hardships. This is consistent with the region south of Najran, which Lehi’s family would have had to pass through to reach the area where trails branch out eastward. Furthermore, whether one assumes they must have reached a fertile, populated area to set up camp or were forced to stop in the midst of the barren desert, either interpretation can be accommodated for within the boundaries established by other criteria for Nahom’s location.

The Historical Geography of Nihm and the Location of Nahom

Thus far, we have assessed all the available details about Nahom provided in the text — except the toponym itself — and found that they all converge together around what might be called “the greater Jawf area,” extending [Page 24]north and south from the Wadi Jawf. No other region is known to fit with all the relevant details in Nephi’s text, and thus Nahom most logically should be situated within this general vicinity — regardless of whether or not an NHM toponym can be documented in this region anciently. Furthermore, a place called NHM located outside of this region would not likely be Nephi’s Nahom, regardless of the similarity in names.

It is within this context that I would like to finally turn our attention to the Nihm region of Yemen and consider whether it falls within the bounds independently established for the location of Nahom. In order to do so, however, we cannot simply rely on the modern borders of Nihm (see Map 5a). While there has been a great deal of stability in the historical geography of this region over time, the tribal geography has experienced periods of change and fluctuation. Thus, we must consider the Nihm tribe’s historical geography, and seek to establish its earliest known borders — only then can we compare its location against Nephi’s record to determine if it fits the criteria outlined for Nahom.

Modern Nihm

In modern times, Nihm has been the name of an administrative district within the Republic of Yemen (since 1990) and was part of the bureaucratic apparatus of the Yemen Arab Republic before then (see Map 5a).154 This modern administrative system was overlaid on a pre-existing tribal structure that goes back centuries, with some aspects even going back millennia. Anthropologist Marieke Brandt explains, “In the 20th century, these tribal territories became the basis of the administrative divisions of northern Yemen; the borders of most of today’s districts (sg. mudīriyyah) and municipalities (sg. ʿuzlah) are congruent with the boundaries of the tribes and tribal sections that inhabit them.”155 Thus, several of the districts and municipalities are identical with the pre-existing tribal territories and bear the tribe’s name.156

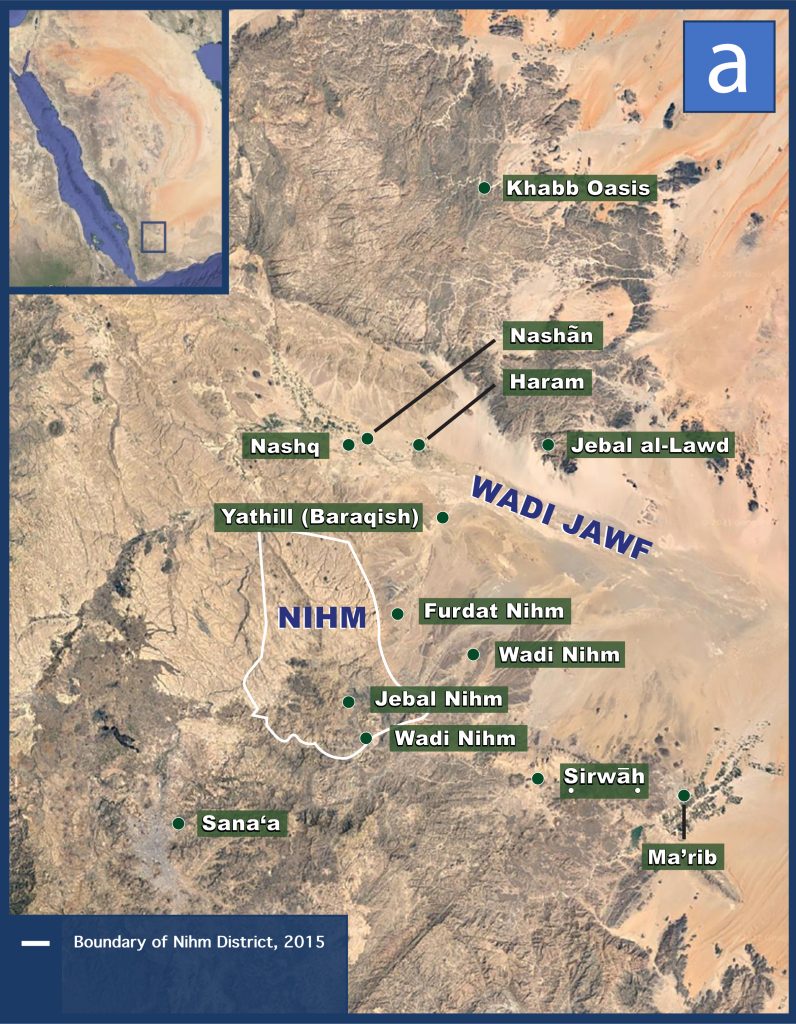

Map 5a. The historical geography of Nihm, present-day district.

The tribal boundaries, however, are not as rigid as those of the official districts, and sometimes a tribe’s territory expands beyond that of its eponymous district.157 Christian Robin’s mapping of the modern Nihm’s tribal territory is significantly more expansive than the present-day district, encompassing roughly five thousand square kilometers (see Map 5b).158 Earlier sources suggest they had approximately the same boundaries throughout much of the twentieth century. For instance, in 1947 Egyptian archaeologist Ahmed Fakhry identified Wadi Hirran as the westernmost border of “the land of the bedouins of Nahm,” which [Page 25]matches the boundaries outlined by Robin nearly forty years later.159 In 1936, British explorer Harry St. John Philby described “Bilad Nahm” (“the country/land of Nahm”) as a region to the west of Wadi Raghwan, suggesting a similar eastern border as that sketched out fifty years later by Robin.160 Various maps from the mid-eighteenth and nineteenth century plotting the name Nehem or Nehhm do not allow us to reconstruct the [Page 26]exact borders of the tribal region but illustrate that it was in the same approximate location more than 250 years ago.161

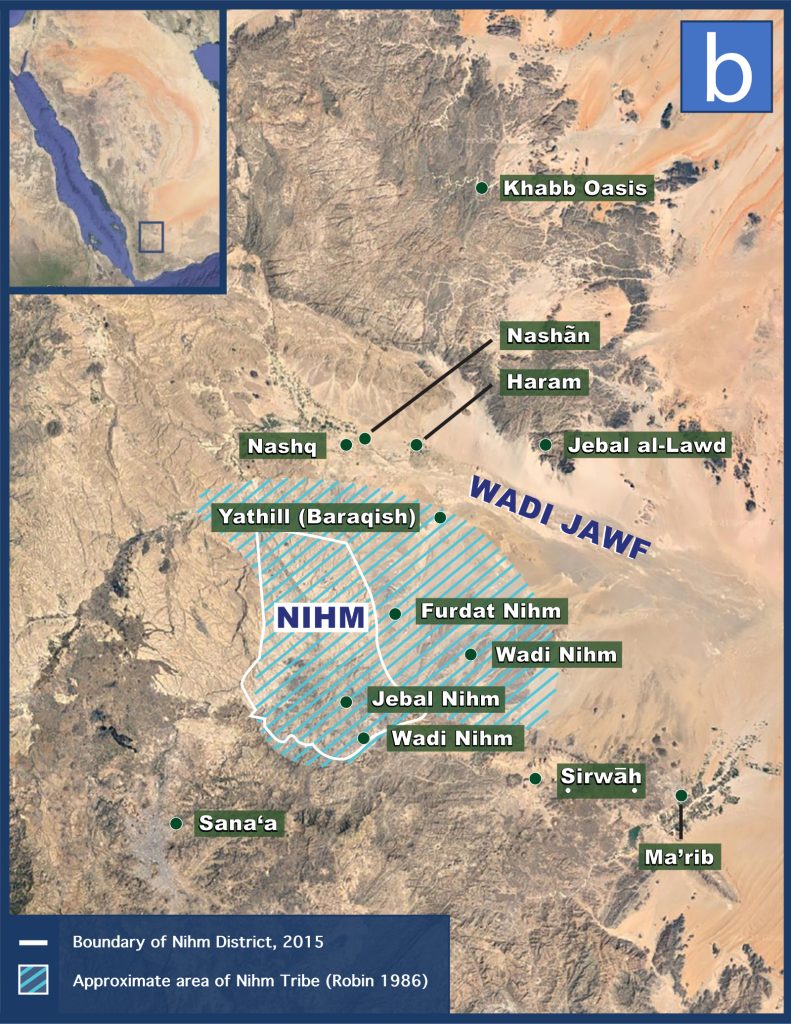

Map 5b. The historical geography of Nihm, 20th century tribal territory.

Nihm in the Early Islamic Period

As noted, aspects of the tribal structure of northern Yemen go centuries, and even millennia, back in time. According to Robert Wilson, “Over the past ten centuries there is little or no evidence of any major tribal [Page 27]movements in this part of Yemen, and the overwhelming impression is one of minimal change, even if tribal alliances have from time to time altered or developed.”162 Wilson noted that in the writings of Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani, the great Arab scholar of the tenth century (ca. 893–945 ad), many of “the tribes listed and the places which they occupied present few surprises to anyone familiar with the positions of the tribes of Bakīl today,” including the Nihm.163

This isn’t to say that there have been no changes and fluctuations in tribal boundaries over the last millennium. Wilson himself documented a number of differences between the tribal boundaries of present-day Yemen and those of the tenth century.164 Christian Robin found both continuity and change in the geography of the Nihm tribe in Hamdani’s writings, noting that they did indeed occupy a similar, though smaller, territory as the present-day tribe on the south side of the Wadi Jawf and also held territory that “extended north of Jawf between the jabal al-Lawdh and the wādī Khabb” (see Map 5c).165 Interestingly, as mentioned earlier, this northern region is exactly where Potter and Wellington concluded Nahom must be located based on the textual evidence from the Book of Mormon — without any awareness of the geographical details in Hamdani’s writings.166

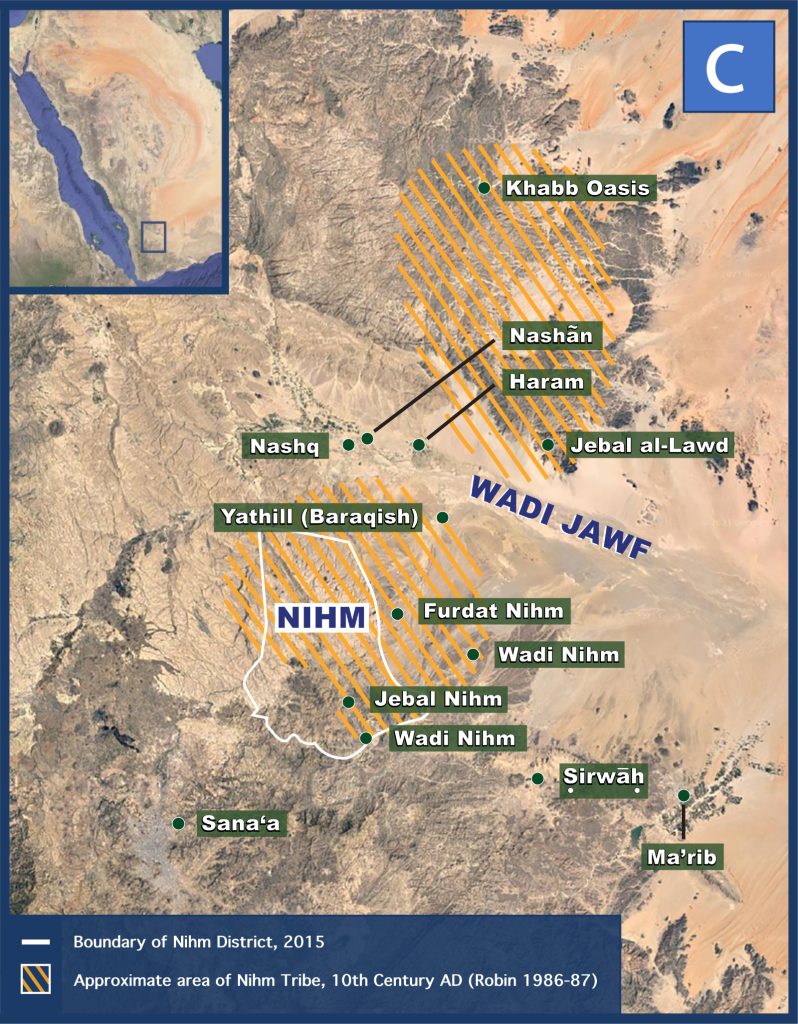

Map 5c. The historical geography of Nihm, 10th century tribal territory.

Earlier Islamic sources indicate that the Nihm were one of the “Arab” tribes within the Hamdan confederation that converted to Islam around the year 630 ad, and a letter from Muhammed himself survives mentioning the Nihm among the Hamdan tribes.167 This does not allow us to confirm their exact borders in these earlier centuries, but Hamdan is the collection of tribes — split into two main sub-tribal groups, Hashid and Bakil — occupying the region north of Sanaʿa going back into antiquity.168 The inclusion of the Nihm among these tribes when they converted to Islam thus indicates that already by the seventh (and likely the sixth) century ad, they were established in the same general area documented in later sources.169

NHM in Pre-Islamic Inscriptions

The continuity and longevity of the Yemeni tribes does not begin with the Islamic era, but extends deep into the pre-Islamic past. As R. B. Serjeant noted, “It is remarkable that tribes today are so generally to be found in the regions they occupied before Islam, though some movement has certainly taken place in the intervening centuries.”170 In recent years, Robin has emphasized that Yemen’s “tribal territorial distribution … is regularly remodelled, with profound modifications in its general inner [Page 28]workings.”171 Yet despite periodic upheavals, he still notes that there has been considerable stability over time:

One of the unique aspects of Yemen is the stability of toponyms during the last 3000 years. Four times out of five, the name of a town, of a valley or of a mountain, recorded in ancient inscriptions, has survived to this day. Some twenty names of tribes also show a very exceptional longevity; this sometimes [Page 29]happens in the same territory; in other cases one can observe a displacement from the desert to the mountains.172

Brandt observes that “the overwhelming impression is one of minimal change of tribal territories, even if tribal structures have altered or developed from time to time,”173 adding that “in some cases, the continuity of tribal names and their related territories spans almost three millennia,” citing Nihm as an example.174

Numerous pre-Islamic inscriptions referring to individuals as nhmy(n) or to a group called nhmt(n) have been found in Yemen (see Table 1).175 It is possible, in light of the meaning of the root nhm in South Arabian languages,176 that the nhmy/nhmt were originally a group of stonemasons who became known as the Nihm tribe.177 Drawing on these inscriptions, various scholars have located the ancient NHM community within the same general region documented for the Nihm tribe in early Islamic sources. For instance, German-Austrian scholar Hermann von Wissmann studied the pre-Islamic inscriptions to reconstruct Yemen’s ancient tribal geography, and concluded based on various inscriptions referring to nhm, nhmyn, and nhmt that in antiquity, that the Nihm occupied the same two regions outlined in Hamdani’s writings (see Map 5c).178 More recently, Peter Stein included NHM, located at present-day Nihm, on his map reconstructing the “geographic horizon” of South Arabian inscriptions carved on palm stalk texts, citing nhmyn in a tribal list found at Nashān (YM 11748).179 Commenting on the altars well-known to Latter-day Saints (DAI Barʾān 1988–2, 1994/5–2, and 1996–1), Burkhard Vogt said the inscription’s author, named Biʿathtar, “comes from the Nihm region, west of Mārib,” thereby situating ancient Nihm in the same general region as the present-day.180

Table 1. NHM in Ancient South Arabian Inscriptions.

| Sigla | Language | Text and Translation | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIH 673 | Sabaic | [h]lkʾmr kbr nhmt bn ʾl[ḏr]ʾ … k[b]r nhmt | [Ha]lakʾamar, chief of the Nihmites, son of ʾIlī[dhar]aʾ … ch[ie]f of the Nihmites | 7th cent. bc |

| Haram 16, 17, and 19 | Sabaic | [ʿm]ʾns¹ bn k[lb]m kbr nh[mt]n | [ʿAmmī]ʾanas son of Ka[l]bum, chief of the Nihmatān | 7th cent. bc |

| DAI Barʾān 1988–2, 1994/5–2, and 1996–1 | Sabaic | bʿṯtr bn swdm bn nwʿm nhmyn | Biʿathtar son of Sawdum, lineage of Nawʿum, the Nihmite | 7th cent. bc |

| RES 5095 | Sabaic | [… w-bn-hw] rʾbm nhmynhn … w-hʿn w-bn-hw (ḥ)mʿṯt n[h]mynhn | [… and his son] Riʾābum, the two Nihmites … and Haʿān and his son (Ḥa)mīʿathat, the two Ni[h]mites | Early Sabaic (8th–4th cent. bc); exact dating uncert[Page 30]ain |

| Gl 1637 | Sabaic | [ʿ]zzm bn […]bm nhmyn mydʿyn | [ʿA]zizum, son of […]BM, the Nihmite, the Mayadaʿite | 5th–4th cent. bc |

| YM 11748 | Sabaic | ḏ-ns²n / bn ns²mr / nhmyn | dhu-Nashān / banu Hashmar / Nihmite | ca. 1st–3rd cent. ad; exact dating uncertain |

| CIH 969 | Sabaic | ṣwr mṯwbm nhmyn | Image of Muthawibum the Nihmite | 3rd cent. ad |

| Ph. 160 n 20 | South Arabian graffito | mdd bn sʿdm nhmyn | Madid, son of Saʿdum, the Nihmite | pre-Islamic; exact dating uncertain |

As previously mentioned, early Islamic sources identify the Nihm as an “Arab” tribe, and Arabs were a separate ethnicity on the margins of South Arabian society in antiquity. Detailed analysis of pre-Islamic inscriptions indicates that the “land of the Arabs” (ʾrḍ ʿrb) in ancient South Arabia was the region to the north of the Jawf, extending up to Najran.181 This is likely why Norbert Nebes believed that in Biʿathtar’s (and thus, Lehi’s) day, the Nihm tribe was “undoubtedly north of the Jawf,” thus correlating it with the northern extension from Hamdani’s time.182 Others have similarly suggested that the Nihm originated as Arabs/Bedouins in the deserts to the north or northeast, and over the course of time migrated south/southwestward to their present day position.183

If the Nihm originated north of the Jawf, it could explain why an individual from Haram bore the title kbr nhmtn in the early seventh century bc (Haram 16, 17, and 19), which some scholars have interpreted as referring to a tribal group called Nahmatan or Nihmatān — likely a variant of Nihm (cf. kbr nhmt in CIH 673).184 As discussed earlier, Haram had trade connections with Najran at this time, and other inscriptions from Haram identify leaders of trading outposts with the title kbr.185 As such, it’s possible that the kbr nhmtn was the leader of a Haramite trading colony located to the north, at an intermediary point between Haram and Najran, within the northern Nihm region.186 The large oasis at Wadi Khabb, near the juncture where the trails coming from the Jawf and Hadramawt converged, would be the most plausible location for [Page 31]such an outpost, and according to von Wissmann a secondary caravan route through the mountains directly connected Najran to Haram, via the Khabb Oasis.187 As noted, this was the northern limit of the Nihm in Hamdani’s time, and von Wissmann argued that “the region of the oasis Ḫabb and the lowlands … in the far eastern semicircle around Ḫabb to the sandy desert are already called NHM in pre-Islamic times,” citing the occurrence of nhm and nhmyn in ancient graffiti texts near Najran (Ph. 160 n 20).188

Even if the Nihm originated in the northern mountains/desert, however, it seems likely their presence to the south of Jawf began in pre-Islamic times, as indicated by von Wissmann, Stein, and Vogt. Some Arabs were known to be “living on or inside the borders” of mainstream South Arabian society, specifically to the south of Wadi Jawf, in pre-Islamic times,189 and evidence from the carved face funerary stelae mentioned earlier indicates that this was so from very early on.190 A burial monument belonging to a nhmyn appears to have come from the southern Nihm region (CIH 969).191 References to nhmyn (or the dual nhmynhn) as “vassals” (ʾdm) and “servants” (ʿbd) to the elites at Ṣirwāḥ (RES 5095 and Gl 1637) also suggest that the Nihm already had a presence in their southern territory by the fifth–fourth century bc, and perhaps even earlier.192 Jan Retsö carefully studied the pre-Islamic geography of the “Arabs” in South Arabian inscriptions, and like von Wissmann he identified branches of the Nihm on both the northern and southern sides of the Wadi Jawf, around the same areas occupied by the Nihm in Hamdani’s writings (see Map 5c).193

Given historical fluctuations in tribal boundaries, it is unlikely the Nihm’s borders in Lehi’s day were identical to those of Hamdani’s time. Yet the boundaries outlined by Hamdani are the earliest that can be established with some degree of certainty, and the general sentiment expressed by various scholars who studied the pre-Islamic NHM texts is that there was continuity or overlap with either the northern or southern locations (and possibly both) of Hamdani’s Nihm going back to the early first millennium bc. Hamdani’s borders thus provide a helpful reference point for the geographic range within which the Nihm were most likely located in Lehi’s day, even if they did not occupy the entirety of both areas at that time.

The Earliest Nihm Borders and the Location of Nahom

Now that we have a better understanding of the Nihm’s earliest known borders and a more comprehensive picture of their potential geographic [Page 32]range, we are in a better position to consider how this may or may not fit with the location of Nahom, as established from the independent criteria in the Book of Mormon.

Remarkably, when the borders of Hamdani’s Nihm are overlaid on a map with the eastward trade routes and turret tomb necropolises, it reveals significant overlap with the eastward turn zone previously defined (see Map 6). Indeed, the earliest known borders of Nihm essentially span the length, north to south, of the eastward turn zone. This means that all the potential eastward routes begin within or near Nihm’s earliest known borders, which in turn virtually guarantees that whatever Nihm’s specific location and boundaries were in Lehi’s day, they would have been in close proximity to a trail eastward across the desert. It is also readily apparent that several of the known burial areas fall within the Nihm’s earliest borders, with others in close proximity just outside those borders. In short, there is effectively a direct convergence between where the independent criteria triangulate the location of Nahom and the earliest known borders of the Nihm tribe.

Map 6. Nihm’s Earliest Known Borders with Turret Tombs and South Arabian

Trade Routes.

According to Dever, as quoted earlier, when such a convergence occurs, “a historical ‘datum’ (or given) may be said to have been established beyond reasonable doubt.” That datum, in this case, being that “the place which was called Nahom” was indeed the Nihm tribal area.194 “To ignore or to deny the implications of such convergent testimony is irresponsible scholarship, since it impeaches the testimony of one witness without reasonable cause by suppressing other vital evidence.”195

Beyond this general correlation, reconstructing a more complete picture of the relevant data now makes it possible to consider and evaluate specific scenarios for the burial of Ishmael and the eastward turn. Starting with the southernmost routes and moving northward, I will review four different possible scenarios (each with potential variations), all of which intersect to some degree with previous theories regarding Nahom and the eastward turn.

1. Wadi Nihm

In one scenario that has been proposed, Lehi and his family get lost along the twisting, confusing trails south of Najran and end up completely by-passing the fertile region in Wadi Jawf and eventually establish an encampment near the mouth of Wadi Nihm, where Ishmael dies.196 From there, no more than a day’s journey southwest through Wadi Nihm would have led the family to the extensive necropolis reported by S. Kent Brown, mentioned earlier.197 Returning northeast to the mouth of Wadi Nihm, some researchers have suggested that the family then continued [Page 33]in a northeast direction for about another day, where they would have then merged with the eastward trail going from the Jawf to Shabwa.198

The mouth of Wadi Nihm, however, is near the main trail leading to Marib, which was only about 35 miles to the east. If they had truly been at risk of starvation when they arrived at Nahom, and had completely by-passed the Wadi Jawf, then it seems more likely that they would have joined this main trail eastward so they could take advantage of the opportunity to restock on provisions at Marib before the longer, more arduous journey across the desert. They could then cut across the desert northeast from Marib (rather than from Wadi Nihm), merging with the trail extending east from the Jawf around the area of Ruwayk (see Map 1), or they could have followed the “eastward arc” of the main trail, as proposed by Brown.

2. Village of Milḥ

Another possibility, that to my knowledge has never been considered, is the necropolis just north of the village of Milḥ, located right in the heart of the modern-day Nihm. This possibility would require that the family continue southward from the Wadi Jawf, entering the northeast corner of Hamdani’s southern Nihm region, before pulling off the trail [Page 34]— perhaps due to an illness or tragedy befalling Ishmael. Depending on exactly where they pulled off the main trail, there are multiple wadi-trails they could have taken into the heart of the Nihm region to reach the necropolis just north of Milḥ. One option would have been to take Wadi Majzar southwest through Furdat Nihm and then cross over a mountain ridge, a journey which took Joseph Halévy and Hayyim Habshush about a day to make by camel (from the opposite direction, starting near Milḥ and going to Majzar).199 If they pulled off the road further to the south, they would simply have to follow Wadi al-Atf into the generally east-west trending Wadi al-Fardah and then continue west about 14 miles (along a route roughly similar to the modern N5 highway) until reaching a broad, flat plain where the necropolis would be less than a mile to the south.

What makes this proposal attractive is that to return to the main road after burying Ishmael, Lehi’s family would essentially just turn around and go back out along Wadi al-Fardah, in a “nearly eastward” direction, merging naturally with the main trail just as it bends eastward and continues on to Marib. Once at Marib, as mentioned previously, they could either continue along the main trail or cut northeast across the desert to merge with the trail that extends east from the Jawf.

3. Wadi Jawf

As previously noted, Warren Aston has long maintained that the Wadi Jawf was the base camp wherein the events of 1 Nephi 16:33–39 unfolded. For example, in 1994 Aston wrote: “Likely the Lehite encampment was in the Jawf valley and Ishmael was carried up into the hills for burial.”200 One of the strengths of this model is it potentially works with either the southern or the northern Nihm, as they could have buried Ishmael on the slopes of Jebal Yām and Jebal Silyām to the south, bordering the southern Nihm and the Jawf, or if we assume a northern Nihm, then Jebal al-Lawd is also a possibility.

Some may wonder why they would have taken Ishmael’s body up to these remote burial areas rather than burying him near one of the Jawf city-states, but to date, no proper burial grounds have been found in association with those sites.201 The one possible exception to this is the “necropolis” outside Barāqish, where some carved face funerary stelae were found, but these burials lacked any human remains, and (as mentioned earlier) may thus have been cenotaphs rather than proper graves.202 All the other funerary stelae from the Jawf were looted from their original context, and no other graves have been found. Furthermore, if there were proper cemeteries with elaborate burial [Page 35]monuments associated with those cities, as some scholars assume, then they may have been reserved for the cities’ elites, not foreigners traveling from distant lands.

Since both the turret tombs in the outlying areas and some of the carved face stelae have been associated with foreigners, caravan traders, and Arabs, the pattern for such groups may have been to bury their dead in the outlying hills or desert in above-ground cairns along the trail, and then make a cenotaph — which were smaller, and thus presumably more affordable than a proper grave — at one of the Jawf cities using the roughly hewn carved face funerary stelae. If Lehi and his family followed this same pattern, they could have buried Ishmael in one of the tombs along the border of Jawf and Nihm, and then perhaps a member of the Nihm tribe with contacts in one of the cities, such as Haram, assisted them in getting a cenotaph made with a memorial stone similar to the “Ishmael Stela” previously mentioned.

After burying Ishmael, Lehi and his family could have then followed the eastward chain of burials marking the way out to either Shabwa or, if a more “nearly eastward” bearing is preferred, the wells of al-ʿAbr and beyond, as Aston has proposed.203

4. Khabb Oasis

In light of the northern extension of the Nihm’s territory in Hamdani’s time, and the possibility that the Nihm occupied at least part of this region in antiquity, it seems worthwhile revisiting Potter and Wellington’s unpublished hypothesis that the events of 1 Nephi 16:33–39 unfolded within this region between Jebal al-Lawd and Wadi Khabb.204 There are no doubt a number of possible scenarios that could be explored, but for the sake of space and simplicity, I wish to merely consider the possibility that the place where the family stopped to “tarry for the space of a time” (1 Nephi 16:33) was the Wadi Khabb, on the northern end of the earliest known Nihm borders.

The main route of the Frankincense Trail likely stopped at the well near the mouth of Wadi Khabb, known today as Bir al-Mahashima.205 Here, the wadi appears every bit as dry and sandy as the rest of this stretch of the trail. If the family were forced to stop at this point due to concerns about Ishmael’s health, they very well could have been concerned about “perish[ing] in the wilderness with hunger” (1 Nephi 16:35). Just around the hills, however, are several patches of fertility. Here, Philby found “quite the forest of tall acacias of the umbrella type” and chased a gazelle into the main wadi channel until coming to “an extensive tract of bushes and trees — Rak, Abal, acacias — at the edge of the hills,” in which he [Page 36]went “wandering about … in search of birds.” Later, he met shepherds who graze their flocks in this area.206 As one wanders into this wadi’s winding mountain canyon and its tributaries, about twelve miles west of Bir al-Mahashima, one encounters an extensive oasis which sustains several towns and villages in modern times.207 According to Habshush, in the nineteenth century grapes and dates grew well here, and the people had well-nourished flocks of sheep.208

While smaller and probably less fertile than Wadi Jawf was in antiquity, this would nonetheless be a more than suitable place for the family to “tarry for the space of a time” (1 Nephi 16:33). The barrenness in the immediate area around the well of Mahashima, near the mouth of the wadi and the edge of the desert, certainly could have left the family initially concerned about “perish[ing] in the wilderness with hunger,” but the discovery of a nearby oasis and wildlife initially hidden behind the hills and sandy plain would have been seen as a great blessing from the Lord allowing them to obtain “food that we did not perish” (1 Nephi 16:35, 39).

Upon Ishmael’s death, Nihmite tribesmen could have guided them down the backtrail to Haram, which modern accounts suggest only takes a couple of days.209 Once in the Jawf, they could have taken Ishmael to Jebal al-Lawd or one of the other burial areas along its borders, as previously discussed. In this scenario, the Book of Mormon Ishmael would be a foreigner connected (if only loosely) to a northern Arab tribe (the Nihm) — the very profile hypothesized for the individual commemorated by the “Ishmael Stela.” Perhaps, as previously suggested, the family’s Nihmite guides used their contacts at Haram to assist the family in procuring a carved face stela as a burial monument. After the burial, the most likely scenario would be that the family stayed in the Wadi Jawf until ready to depart again, at which point they could have taken the eastward trail that leads out across the desert, as discussed above.