Abstract: The first oral draft of the Book of Mormon dictated by Joseph Smith reflected remarkable literary refinement and complexity. Such observations demonstrate that he exhibited highly developed composition and oratory skills. To date, no scholar has attempted to describe the specific skills Joseph manifested while dictating. This essay addresses whether Artificial Intelligence (AI) could generate an accurate list of the skills necessary. It begins by identifying and informally testing eleven chatbots to see if they can accurately predict the skills needed to perform a task. Seeing success, they are next asked a long question about the skills needed to dictate a book like the Book of Mormon. Fifteen skills are common in the responses from the eleven chatbots, which are compiled into a list. The list is then validated by appealing to experts in the field of literary composition. Next, his documentable 1829 skills are cross-referenced to the list. The historical reality is that none of Joseph’s personal acquaintances describe him as accomplished with the skills that AI calculated would be needed. This AI “fail” deserves additional investigation. If eyewitnesses accurately reported he lacked the predicted skills, what skills did AI miss and what skills enabled him to dictate the Book of Mormon?

[Editor’s Note: This article is an updated version of a paper first presented at the 2024 FAIR Virtual Conference. Those interested in the original presentation can find it at fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/virt_2024-history/skills-needed-to-dictate-book-of-mormon.]

[Page 258]For nearly three months in 1829, Joseph Smith dictated a 269,320-word manuscript that became the 1830 Book of Mormon.1 He attributed his ability to produce the words to supernatural assistance—the “gift and power of God.”2 Predictably, most secular observers reject these claims. Some postulate Joseph Smith received outside help from collaborators or a preexisting manuscript. Others hypothesize that mental illness, trances, or hallucinogens enhanced his cognitive abilities. Most of those theories have been debunked, and skeptics have moved on to other speculations.3

Currently, the most popular secular theory describes how Joseph Smith’s natural cognitive abilities were sufficient to accomplish the task.4 As Eran Shalev observes: “Historians have long denied Smith the [Page 259]image of the ignorant rural boy who could not have acquired all the material that he would have needed to write The Book of Mormon.”5 Similarly, after mentioning “some 6,000-plus titles” that scrutinize the “empirical claims” of Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon, Richard S. Van Wagoner declared: “The main conclusion of this particular growing body of work is that there is no element in the Book of Mormon that cannot be explained naturalistically.”6 Fawn Brodie agreed: “The source of his [Joseph Smith’s] power lay not in his doctrine but in his person, and the rare quality of his genius was due not to his reason but to his imagination. He was a mythmaker of prodigious talent.” And “His talent, it is true, was not exceptional, for his book lacked subtlety, wit, and style. He was chiefly a tale-teller and preacher.”7 In his biography, The Making of a Prophet, Dan Vogel consistently reflects this idea, explaining that the process “was a more-or-less stream-of-consciousness composition,” dictated “mostly impromptu and without the aid of notes.”8

Beyond the supernatural versus natural debate, it is undeniable that Joseph Smith exhibited proficient literary skills every day for almost three months in 1829 as he spoke the first draft of the Book of Mormon.9 Curiously, among the thousands of research studies [Page 260]exploring the book and its origin, none have attempted to identify those skills generally or specifically. Admittedly, such an approach assumes a naturalistic origin for the word-stream, which Latter-day Saint researchers might consider faithless. However, secular scholars have similarly avoided this inquiry (with one exception discussed below). The question, “What literary skills did Joseph Smith exhibit while dictating the Book of Mormon?” remains unanswered and largely unaddressed.

Recently, Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots have boasted their ability to answer complex questions using English language interfaces. Part of the new usefulness of AI is advancements in natural language processing that enable it to understand and reply in everyday speech. These advancements, coupled with its training on large amounts of data, sometimes measured in petabytes, from text-based sources like websites, books, articles, and other publications, allow AI modules to respond to questions regarding the skills a person would need to accomplish a specific task. Recognizing this, I explored what AI might contribute to the question regarding the skills Joseph Smith manifested while dictating the Book of Mormon.

The remainder of this article is divided into four parts. Part One identifies eleven chatbots and informally tests them for accuracy. Part Two discusses the challenges of formulating the proper question (regarding the skills needed to dictate the Book of Mormon) to pose to the AI modules. Part Three compiles fifteen of the most popular skills mentioned by the chatbots and tests their validity. Part Four then brings us back to Joseph Smith to identify which skills the historical record shows he possessed in 1829 and whether they correlate to AI predictions.

Part One: Choosing and Testing Artificial Intelligence Chatbots

This study queried only free-of-charge and free-trial AI modules. Included were Microsoft Bree, ChatGPT 4o, Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft Copilot, Google Gemini, LDSBot, iAsk.AI, Meta AI, Inflection’s PI, Quora’s POE, and Perplexity.10 Some of these chatbots [Page 261]are derivatives of others. For example, LDSbot is based on an older version of ChatGPT, which means that posing questions to LDSbot might be considered more as a second query to ChatGPT. However, all the chatbots were accessed through distinct online portals, supporting differences in their use of the underlying AI programming. Regardless, their answers consistently reflected beneficial diversity and were included.

In all, nine different questions were posed to the eleven chatbots. This essay only mentions five of them. However, all of the 99 raw responses can be downloaded at ldsperspectives.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/11-AI-Chatbot-Answers-to-9-Questions-BofM.pdf.

Informally testing chatbot accuracy

For the past few years, Artificial Intelligence has received increasing media coverage. Reports outlining AI chatbots’ remarkable abilities are usually accompanied by accounts of occasional errors and even extreme blunders. Aware of these reports, I sought to first test their responses informally by asking them four questions:

- What skills would I need to safely anesthetize a person for surgery?

- What skills would I need to be a chef in a restaurant?

- What skills would I need to fix an automobile?

- What skills would I need to play for the Los Angeles Lakers?

As a retired anesthesiologist, I felt competent evaluating the accuracy of the answers to the first question. Having less expertise with the remaining three questions, I could only detect obvious inaccuracies. My review of all 44 responses (one from each chatbot for each of the four questions) failed to identify even one egregious error. Regarding anesthesia, the chatbots provided consistently correct information; the responses to the other three questions seemed equally defensible. In summary, all of the answers offered by the individual chatbots seemed accurate to me.

After this initial exercise, I concluded that AI responses can provide a starting point for thinking about task-related skills. The possibility of error requires that their predictions be treated as suggestions, like brainstorming-level ideas to address a problem. But their responses are far from useless. The potential for inaccuracy is real but should not be interpreted as expected inaccuracy. Expert validation or [Page 262]invalidation is always required, but the initial responses can provide a valuable jumpstart to answering the questions at hand.

Part Two: Formulating the Proper Book of Mormon Author-Skills Question

A key to successful AI chatbot interactions is providing accurate details in the wording of the original questions. As with all computer programming, the AI output depends on the input. The saying, “garbage in, garbage out” consistently applies. Consequently, multiple variables, including the syntax and composition of the question, may significantly influence the answers. The AI module’s previous learning input is also vital.

Accordingly, formulating a question with the proper phrasing and content is integral to obtaining useful data from the chatbots. Initially, I wanted to ask: “What skills would I need to dictate in three months a 269,320-word book with the literary characteristics of the Book of Mormon?”11 However, since no scholar has published a comprehensive list of Book of Mormon literary characteristics, AI chatbots would have to guess at that part of the question. Possibly, they could glean a characteristic or two from available published writings. Yet, borrowing an entire list is currently impossible. Neither would AI algorithms automatically perform their own deep textual analyses of the Book of Mormon in order to generate a list of literary characteristics. They are not programmed to function that way.

Identifying Book of Mormon literary characteristics

To improve the chances of receiving useable responses, specific Book of Mormon literary characteristics were identified so they could be included in the question posed to the AI chatbots:

- 269,320 words.12

- [Page 263]Unique words: about 5,600.

- College-level vocabulary words: dozens.13

- Reading level: eighth grade.14

- Storylines: 77 major plus more minor.15

- Characters: 207.16

- Socio-geographic groups: 44.17

- Geographical locations in the “promised land” world: 147.18

- Number of separate travels between specific locations: over 400.19

- Original proper nouns: 170.20

- [Page 264]Distinct titles for the primary protagonist: over 100.21

- Chronological systems: 3.22

- Flashbacks and embedded storylines: 5.23

- Genealogies greater than twenty generations: 2.24

- Ecological references: 2,065.25

- Sermons: 63 comprising over 87,000 words.26

- Sermon topics: over 80.27

- Parallel poetic devices like chiasmus: over 400.28

- [Page 265]Bible intertextuality: at least 650 allusions and similar phraseology.29

- Subjects discussed with precision include biblical law, olive tree husbandry, and warfare tactics.30

An additional characteristic is that no full-sentence edits have been applied to the original dictation.31

Combining literary characteristics into the form of a question

Most of these Book of Mormon literary features are objective qualities found in the text of the book, although subjectivity is evident in some. These can be compiled into one question:

[Page 266]What skills would be needed to mentally create and dictate in three months without written notes a book with 269,320 words using about 5,600 unique words, including dozens of college-level vocabulary words, and reads at an eighth-grade level with the following characteristics: 77 storylines; 207 named characters; 44 socio-geographic groups; over 100 geographical locations in the imagined world; over 400 geographic movements by characters; over 170 original English proper nouns; over 100 distinct titles for the primary protagonist; three chronological systems; several lengthy flashbacks; two genealogies with greater than twenty generations; 100s of ecological references; at least 63 religious speeches comprising over 87,000 words discussing over 80 Christian themes; hundreds of parallel poetic devices like chiasmus; hundreds of intertextual King James Bible phrases; and discussing with precision subjects like biblical law, olive tree husbandry, and warfare tactics. Also, no full-sentence edits are afterward permitted.

This question was presented verbatim to the eleven AI chatbots through their the interfaces on their respective websites.32

Part Three: Compiling and Testing the Most Commonly Predicted Skills

Ten of the chatbots seemed oblivious to the possibility that the question above described an actual historical event. Only LDSBot connected it to Joseph Smith, reporting: “The skills required to accomplish something like that would be pretty remarkable. From a Latter-day Saint perspective, Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon is often seen as a remarkable accomplishment, attributed to divine inspiration.”33 Of the eleven responses, ChatGPT 4o provided the most comprehensive reply:

Creating and dictating such a complex book in three months, without written notes and without permitting full-sentence edits afterward, is a monumental task. It requires a combination of advanced skills and capabilities in various areas. Here’s a detailed list of the skills and attributes needed:

[Page 267]Cognitive and Memory Skills

- Exceptional Memory: Ability to retain vast amounts of detailed information about storylines, characters, locations, and other elements without written notes.

- Mental Organization: Organize the entire book structure, including intricate details, in your mind.

Advanced Language and Vocabulary Skills

- Vocabulary Management: Use a diverse vocabulary of around 5,600 unique words, including advanced terms, while maintaining an eighth-grade reading level.

- Language Simplification: Simplify complex ideas and vocabulary to make them accessible to an eighth-grade audience.

- Precision and Clarity: Communicate ideas clearly and precisely, avoiding ambiguity.

Dictation Proficiency

- Clear Articulation: Speak clearly to ensure accurate transcription by dictation software.

- Consistent Pacing: Maintain a steady pace that balances speed with clarity and accuracy.

- Natural Speech Patterns: Dictate in a way that sounds natural and engaging, avoiding overly complex sentence structures.

Creative and Analytical Skills

- Creative Visualization: Vividly imagine scenes, characters, and settings to describe them in detail.

- Complex Plotting: Weave multiple storylines, character arcs, and flashbacks seamlessly into the narrative.

- Analytical Thinking: Ensure logical consistency and coherence in the story, characters’ actions, and plot developments.

Planning and Structuring

- Comprehensive Mental Outline: Develop a detailed mental outline of the book’s structure before starting.

- Story Structure Management: Ensure the book has a coherent structure with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

- Chronological Management: Handle multiple chronological systems and flashbacks with precision.

Concentration and Focus

- Sustained Focus: Maintain deep concentration for extended periods to dictate large volumes of text.

- Distraction Management: Minimize distractions and maintain mental clarity during dictation sessions.

Self-Discipline and Motivation

- Daily Commitment: Dictate consistently every day to meet the word count goal (approximately 2,993 words per day).

- Resilience: Stay motivated and push through any mental fatigue or writer’s block.

[Page 268]Time and Stress Management

- Effective Scheduling: Allocate specific times each day for dictation to ensure consistent progress.

- Stress Reduction Techniques: Use techniques to manage stress and prevent burnout.

Technological Proficiency

- Dictation Software: Use high-quality dictation software that can accurately transcribe your speech.

- Error Handling: Quickly correct minor transcription errors during the process to maintain the flow of dictation.

Specific Subject Matter Expertise

- Biblical Knowledge: Deep understanding of biblical law, themes, and the ability to integrate King James Bible phrases.

- Specialized Knowledge: Expertise in subjects like olive tree husbandry and warfare tactics.

- Ecological Understanding: Familiarity with a wide range of ecological references relevant to the story.

Literary and Rhetorical Skills

- Poetic Devices: Ability to use parallel poetic devices like chiasmus effectively.

- Intertextuality: Integrate intertextual references to the King James Bible seamlessly.

- Speech Writing: Craft compelling religious speeches that discuss Christian themes with depth and clarity.

Organizational and Tracking Skills

- Character Management: Keep track of 207 named characters, their movements, and interactions.

- Geographic Awareness: Manage over 100 geographical locations and over 400 geographic movements by characters.

- Proper Nouns and Titles: Remember and consistently use over 170 original English proper nouns and 100 distinct titles for the primary protagonist.

- Genealogical Tracking: Maintain accuracy in genealogies spanning over twenty generations.

Religious and Thematic Integration

- Thematic Consistency: Integrate and discuss over 80 Christian themes with precision.

- Religious Discourse: Compose and deliver lengthy religious speeches that are coherent and impactful.

Environmental and Support Systems

- Conducive Environment: Create a quiet, distraction-free environment for dictation.

- Support Network: Engage with a support network for encouragement and feedback, if possible.

[Page 269]Problem-Solving Skills

- On-the-Fly Editing: Make immediate minor adjustments to ensure the overall quality and coherence of the dictated content.

- Adaptability: Quickly adapt to any issues that arise during the dictation process.

By mastering these skills and maintaining a disciplined approach, you can tackle the daunting task of creating and dictating such a complex and detailed book within the specified constraints.

Summarizing chatbot responses

Table 1 summarizes the fifteen most commonly mentioned skills across the chatbot responses.34

Table 1. Summary of the most popular skills identified by eleven AI chatbots.

| AI-identified skills needed to dictate a book with characteristics of the Book of Mormon | Bree AI | Chat GPT 4o | Claude | Copilot | Gemini | LDSBot | iAsk.AI | Meta AI | Perplexity | PI | POE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention to detail | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Biblical and religious knowledge | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Creativity-imagination | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Discipline-stamina | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Editing | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Memory | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Mental focus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Organizational | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Religious composition | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Research-specialized knowledge | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Speaking—dictation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Storytelling | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Time management | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Vocabulary-language | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| World-building | X | X | X | X | X | X |

[Page 270]The eleven chatbots identified dozens of additional major and minor skills, but the chart is representative of those most commonly reported.

Validating the list of skills—appealing to author-experts

As discussed above, AI predictions require independent validation from experts for their results to be considered correct. While less scientific, I corroborated the results through four exercises. For the first, I reasoned that such endorsement could be made by authors who have written long, complex books, even if not dictated. Over the past two decades, Three of the books I have authored have more than 200,000 words: Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2006) with 240,864 words; Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2013), volume one with 274,402 words and volume two with 235,367 words. After carefully reviewing the list of fifteen skills and having read the Book of Mormon dozens of times, I concluded that all are needed, and the list is reasonably accurate.

William L. Davis’s Visions in a Seer Stone validates most of the list

A second validation comes unintentionally from William L. Davis’s 2020 book, Visions in a Seer Stone: Joseph Smith and the Making of the Book of Mormon. Davis is the only author to approach Joseph Smith’s production of the Book of Mormon by looking at it through the lens of skill sets. He also considers the Book of Mormon to be “the result of Smith’s individual creative efforts,” the result of Joseph’s natural intellect and abilities.35 Despite flaws in documentation and logic, Visions in a Seer Stone represents a milestone in Book of Mormon studies and hopefully a watershed moment in naturalistic treatments of its origin (see Appendix B).

The skills-based approach in Visions in a Seer Stone focuses primarily on one specific oratorical ability. Called “laying down heads,”36 Davis portrays how the ability enabled Joseph Smith to dictate the Book of Mormon.37 “Laying down heads” is composed of three skills linked together. First is the ability to compose summary headings (of the material to be recited) and to organize them into outlines; [Page 271]second is to memorize and recall the outlines in real time; and third is to speak extemporaneously to fill in the outlines with pre-memorized or spontaneously-invented narrative details. The word “outline” is mentioned over 300 times in Visions in a Seer Stone and is a primary theme in the theory Davis presents.38

Throughout its pages, Visions in a Seer Stone depicts Joseph Smith exhibiting more than the three skills needed to lay down heads. Most of these abilities are not directly discussed or highlighted. Instead, they show up when needed, generally without exploring how he might have learned or acquired them. In all, twelve of the fifteen skills identified by AI chatbots are attributed by Davis to Joseph (directly or indirectly) as he dictates the Book of Mormon, as demonstrated in table 2.

Table 2. AI-identified skills and the page numbers in Visions in a Seer Stone where it is asserted that Joseph demonstrated those skills.

| AI-identified skills needed to dictate a book with characteristics of the Book of Mormon | Was the skill attributed to Joseph Smith in Visions in a Seer Stone? | Page numbers depicting Joseph Smith needing or demonstrating the skill |

|---|---|---|

| Attention to detail | Yes | 105, 122, 146, 150, 155, 156, etc. |

| Bible and theology | Yes | 3, 7, 108, 110, 113, 125, 178, etc. |

| Creativity-imagination | Yes | xi, 58, 61, 90, 108, 158, 162, etc. |

| Discipline-stamina | Not mentioned | – |

| Editing | Yes | 2, 135, 143, 163, 190, 224, etc. |

| Memory | Yes | 23, 24, 34, 46, 51, 80, 138, 143, etc. |

| Mental focus | Not mentioned | – |

| Organizational | Yes | 16, 17, 80, 86, 105, 121, 131, 140, etc. |

| Religious composition | Yes | 8, 17, 22, 25, 81, 90, 117, 120, etc. |

| Research-specialized knowledge | Yes | 44, 48, 57, 173, etc. |

| Speaking—dictation | Yes | 4, 36–38, 49, 105, 110–16, etc. |

| Storytelling | Yes | vii, 3, 4, 87, 127, 158, 168, 193, etc. |

| Time management | Yes | 49, 58, 61, 163–65, 190, 192, etc. |

| Vocabulary-language | Yes | x, 113, 133, 163, 92, 168, 175, etc. |

| World-building | Not mentioned | – |

[Page 272]By describing Joseph Smith employing twelve of these fifteen skills during the dictation, Visions in a Seer Stone indirectly corroborates the necessity of the AI-generated skills list.

Additional validation of the fifteen skills

A third validation is implied by consulting books written by experts on composition, creative writing, and oratory.39 These fifteen skills are repeatedly discussed in the respective books and referenced in their indexes, which illustrate that the list seems highly defensible from a literary standpoint.

The final observation involves how critics of any specific skill would need to successfully argue it was nonessential. They would need to explain how a long, complex, and literarily refined first draft narrative could be mentally created and dictated by an author lacking that particular skill. It appears such reasoning would be unsuccessful since all the skills can be rationally defended as at least contributory. Alternatively, skeptics could provide a reliable historical account describing how an author has duplicated this process using their intellect but without employing that particular skill.40

[Page 273]Part Four: Comparing to Joseph Smith’s Documentable Skills

The final portion of this paper compares the fifteen AI chatbot skills to Joseph Smith’s 1829 documentable skills.41 Due to limitations in the documentary record, some skills are evaluated together in the sections below.

Attention to detail, discipline and stamina, mental focus, organizational, and time management skills

Unfortunately, most accounts describing Joseph Smith before age twenty-three do not directly address his attention to detail, personal discipline and stamina, mental focusing capability, organizing ability, or time management skills. However, historical references to his general ambition and resourcefulness in the 1820s reveal a common theme of alleged laziness.42 Neighbor Christopher M. Stafford related in 1885: “Jo was the laziest one of the family.”43 Pomeroy Tucker wrote:

The larger proportion of the time of the Smiths, however, was spent in hunting and fishing, trapping muskrats (“mushrats” was the word they used), digging out woodchucks from their holes, and idly lounging around the stores and shops in the village. Joseph generally took the leading direction of the rural enterprises mentioned, instead of going to school like other boys—though he was seldom known personally to participate in the practical work involved in these or any other pursuits.44

[Page 274]Another writer, Orsamus Turner, also used the terms “lounging” and “idle” to describe Joseph, but he admitted, “Joseph had a little ambition; and some very laudable aspirations.”45 Neighbor Orlando Saunders remembered Joseph “was a good worker.”46

In 1831, James Gordon Bennett toured upstate New York with Martin Van Buren (the future United States President) and Nathaniel S. Benton.47 Bennett did not personally meet Joseph Smith during that visit but soon after, published the rumors he heard:

Young Joe, who afterwards figured so largely in the Mormon religion, was at that period a careless, indolent, idle, and shiftless fellow. He hung round the villages and strolled round the taverns without any end or aim—without any positive defect or as little merit in his character. He was rather a stout able bodied fellow, and might have made a good living in such a country as this where any one who is willing to work, can soon get on in the world. He was however, the son of a speculative Yankee pedlar, and was brought up to live by his wits.48

Bennett, then a freelance newspaper writer, had little to gain by misrepresenting the gossip he encountered; neither was he apparently worried about its accuracy. Whether true or not, this glimpse into the general tales describing Joseph Smith in 1831 supports that he was not then known as energetic or enterprising. If he had been training in the years before 1829 to acquire the skills needed to dictate a long book, he evidently was successful at keeping his efforts secret from the general neighborhood.

Bible and theology skills

Conflicting historical accounts from Joseph Smith’s contemporaries describe his early familiarity with the Bible. John Stafford, who grew [Page 275]up with the Smiths in Manchester, recalled that the Smith family “studied the Bible” in their home school.49 Similarly, an unidentified Western New Yorker told William Kelley in 1881: “they [the Smith family] had school at their house and studied their Bible.”50

In 1882, Stephen S. Harding wrote to Thomas Gregg saying Joseph “was familiar with the Scriptures, and never tired of reading the miracles in the Old Testament and in the New.”51 A. W. Cowles recalled: “He [Joseph Smith] read the Bible, especially its historical narratives and prophecies.52 Pomeroy Tucker provided this description:

As he [Joseph Smith] further advanced in reading and knowledge, he assumed a spiritual or religious turn of mind, and frequently perused the Bible, becoming quite familiar with portions thereof, both of the Old and New Testaments; selected texts from which he quoted and discussed with great assurance when in the presence of his superstitious acquaintances. The Prophecies and Revelations were his special forte. His interpretations of scriptural passages were always original and unique, and his deductions and conclusions often disgustingly blasphemous, according to the common apprehensions of Christian people.53

Tucker added: “The final conclusion announced by him [Joseph Smith] was, that . . . the Bible [was] a fable.”54 In contrast, Joseph taught that the Bible was “the word of God as far as it is translated correctly” (Article of Faith 8). So, it is unclear whether Tucker based his report upon firsthand recollections or possibly derived it from the Book of [Page 276]Mormon’s criticism of the Bible.55 In contrast, Orson Pratt, who first met Joseph Smith in 1830, summarized:

This young man was not learned, like those educated in colleges and theological institutions; indeed, he was a farmer’s boy, unacquainted with the arguments, and the tenets, and the creeds, and the institutions of religion that existed around him . . . a young man not versed in the Scriptures any more than most of the common lads of that age. And we all know that there are but a very few among farmers that have the opportunity of informing their minds at so early a period—at the age of twenty-one, in regard to the doctrines and prophecies contained in the Scripture.56

Additional accounts from eyewitnesses corroborate Joseph Smith’s limited biblical knowledge. Lucy Mack Smith quoted a youthful Joseph saying: “I can take my Bible, and go into the woods and learn more in two hours than you can learn at meetings in two years, if you should go all the time.”57 But she also noted that by 1823 Joseph had “never read the Bible through in his life.”58 Similarly, David Whitmer remembered that “Smith was ignorant of the Bible” at the time of translation of the Book of Mormon.59 Emma Smith told Edmund C. Briggs in 1856 that Joseph “had such a limited knowledge of history at that time that he did not even know that Jerusalem was surrounded by walls.”60 Years later, in 1877, Emma repeated the story to Nels Madsen and Parley P. Pratt Jr.: “He had not read the Bible enough to know that there were walls around Jerusalem.”61

[Page 277]Joseph’s not knowing of the walls around Jerusalem is often repeated as evidence of his ignorance of the Bible. However, he described several times how he “searched the scriptures” as a youth.62 He remembered how, after reading James 1:5, he retired to a grove of trees to pray vocally in 1820. Accounts depicting Joseph Smith as ignorant of the Bible are undoubtedly in error. However, it is also clear his familiarity was limited, and few verses, if any, had been committed to memory by 1829.

Composition, editing, vocabulary, and language

Unfortunately, Joseph Smith wrote very little before dictating the Book of Mormon; if he if he had written even moderately, virtually none of his handwritten communications survived. This reality makes evaluating his composition, editing, and language skills by reviewing his 1820s literary works impossible.

Nonetheless, multiple eyewitnesses left relevant historical observations. In an 1842 account, Orson Hyde observed: “He could read tolerably well, but he wrote very poorly, and had but little knowledge of rhetoric.”63 David Whitmer described Joseph Smith as “quite illiterate, knew nothing of grammar or composition.”64 He was “little versed in Biblical lore, was ofttimes compelled to spell the words out, not knowing the correct pronunciation.”65 In 1884, Martin Harris recalled: “I was Joseph Smith’s scribe, and wrote for him a great deal; for he was such a poor writer, and could not even draw up a note of hand as his education was so limited.”66 John H. Gilbert recalled the Book of Mormon [Page 278]manuscript “was not punctuated at all,” declaring: “They [Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery] did not know anything about punctuation.”67

In an 1875 account, Joseph’s brother, William, specifically addressed Joseph’s writing abilities in the 1820s:

It is to be remembered that Joseph Smith was only 17 years of age [in 1823] when he first first began his profesional career in the Minestrey. That he was illitterate to some extent is admitted but that he was enterly [entirely] unlettered is a mistake. In Sintax, orthography Mathamatics grammar geography with other studies in the Common Schools of his day he was no novis and for writing he wrote a plain intelegable hand.68

William refers to Joseph as “no novis,” regarding syntax (sentence formation), orthography (spelling), mathematics, grammar, and geography. Yet he also states that Joseph was then “illiterate to some extent,” suggesting his progress was limited. Orson Pratt agreed:

His education was limited to a slight acquaintance with two or three of the common branches of learning. He could read without much difficulty, and write a very imperfect hand; and had a very limited understanding of the ground rules of arithmetic. These were his highest and only attainments; while the rest of those branches, so universally taught in the common schools throughout the United States, were entirely unknown to him.69

Memory and recall

Assessing Joseph Smith’s 1829 memory and recall ability is difficult due to a lack of specific evidence. No eyewitness statements describe him possessing extraordinary recall or a photographic [Page 279]or eidetic memory. Likewise, through thousands of pages of their publications, biographers Fawn Brodie, Richard Bushman, George Q. Cannon, G. Homer Durham, Donna Hill, Preston Nibley, Lucy Mack Smith, Edward W. Tullidge, Dan Vogel, and John A. Widtsoe describe many of his personal qualities.70 Yet, none portray him as possessing a phenomenal memory. Equally, none of the transcripts published in Dan Vogel’s five-volume series Early Mormon Documents describe Joseph Smith as having an extraordinary ability to memorize and remember. Neither did Joseph Smith’s brother-in-law, Michael Morse, describe him as capable of producing the Book of Mormon using his memory and other cognitive skills.71

Joseph Smith’s attempt to learn Hebrew in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1836 demonstrated his memory and recall skills seven years after dictating the Book of Mormon. Professors Elvira V. Masoura and Susan E. Gathercole observe: “Research has revealed a close link between language acquisition and the capacity of the verbal component of working memory.”72 After attending the Hebrew classes taught by Joshua Seixas, Joseph learned to translate Hebrew into English satisfactorily but without becoming proficient.73 In contrast, Orson Pratt mastered [Page 280]the language enough to be certified as a teacher.74 Pratt bested him on that occasion, indicating an upward limit to Joseph Smith’s memory capacity. Overall, his youthful memory abilities seemed at least average, but not prodigious.

Research and specialized knowledge

Most available data support the idea that Joseph Smith possessed a limited understanding of the world beyond his immediate surroundings in 1829. He may have read his father’s newspapers, which would have expanded his views. Orsamus Turner remembered: “Once a week he [Joseph Jr.] would stroll into the office of the old Palmyra Register, for his father’s paper.”75 The Palmyra Register was published between 1817 and 1821, indicating that Joseph would have been between eleven and fourteen. William E. McLellin described Joseph Smith’s knowledge of science in 1834:

I was personally and intimately acquainted with Joseph Smith <the man who read off the> the translation of the book, for five years near the beginning of his ministry. He attended my High school during – <the winter> of 1834. He attended my school and learned science all winter. . . . When I took him into my school, he was without scientific knowledge or attainments.76

After hearing Joseph Smith speak in 1844, Josiah Quincy reported that Smith’s “comments, though rambling and disconnected, were delivered with the fluency and fervor of a camp-meeting orator.” And, “he talked as from a strong mind utterly unenlightened by the teachings of history.”77

During the months and years immediately after the 1830 publication of the Book of Mormon, critics sought plausible explanations for the source of its words to counter Joseph Smith’s claims of divine [Page 281]inspiration. However, among their accusations, no acquaintances remembered him writing or hiding a manuscript. None of the local storekeepers described him (or an accomplice) buying ink and paper in quantities not inconsistent with letter-writing or penmanship practice. No recollections from his contemporaries mention him visiting libraries or bookstores to read, borrow, or buy their books. Even ambiguous recollections of 1820–1829 might have been spun into evidence of Joseph’s fabrication of the words. Yet, little or no supportive historical data has been found.78 In addition, other documentable activities likely competed for his time and resources, like farming, clearing land, treasure-seeking expeditions, maple sugar production, schooling, and day-labor employment.79

Creativity, imagination, and world-building skills

Among the skills needed to replicate Joseph Smith’s dictation of the Book of Mormon, AI chatbots repeatedly refer to creativity, imagination, and world-building. In her recollections, Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph’s mother, recounted the family recitals that he delivered around 1823 when he was in his seventeenth year:

During our evening conversations, Joseph would occasionally give us some of the most amusing recitals that could be imagined. He would describe the ancient inhabitants of this continent, their dress, mode of travelling, and the animals upon which they rode; their cities, their buildings, with every particular; their mode of warfare; and also their religious worship. This he would do with as much ease, seemingly, as if he had spent his whole life with them.80

If Joseph’s stories originated in his imagination, this recollection could be evidence of his creativity and an effort to hone rhetorical [Page 282]skills as a youth. That scenario does not fit recollections from Joseph’s younger brother, William, who witnessed those recitals:

Knowing that he [Joseph Smith] was very young, that he had not enjoyed the advantages of a common education; and knowing too, his whole character and disposition, they were convinced that he was totally incapable of arising before his aged parents, his brothers and sisters, and so solemnly giving utterance to anything but the truth.81

William also described how Joseph was incapable of authoring a “historey of a once enlightned people, their rise their progress, their origin, and their final over throw that once in habited this american Continent.”82

Lucy Mack Smith also reported that the details he related in those family gatherings, including references to “the ancient inhabitants of this continent,” originated with the angel Moroni.83 Concerning Lucy’s account, H. Donl Peterson notes: “From Mother Smith’s report we can see that the visions that accompanied Moroni’s instructions were vivid.”84 It is also possible that Lucy’s memory faltered when recalling some details. Jeff Lindsay points out that the Book of Mormon

has no descriptions of people riding animals in over 500 pages that include several major migrations and 100 distinct wars. It provides no notably detailed descriptions of clothing (other than armor) and no detailed descriptions of the structure of later buildings. The most detail we get involves descriptions of fortifications with palisaded walls and ditches.85

[Page 283]Speaking, dictation, and storytelling

The historical record describes Joseph Smith’s involvement in a few oratory activities n the 1820s. In 1893, Daniel Hendrix recalled that Joseph Smith “was a good talker and would have made a fine stump-speaker if he had had the training.”86 According to several sources, Smith attended Methodist meetings but never joined the church. Pomeroy Tucker wrote:

Protracted revival meetings were customary in some of the churches, and Smith frequented those of different denominations, sometimes professing to participate in their devotional exercises. At one time he joined the probationary class of the Methodist church in Palmyra, and made some active demonstrations of engagedness, though his assumed convictions were insufficiently grounded or abiding to carry him along to the saving point of conversion, and he soon withdrew from the class.87

In 1851, Orsamus Turner recalled that Joseph Smith “was a very passable exhorter” at Methodist camp gatherings.88 Joseph’s informal involvement with the Methodists may have lasted only a few months, from the fall of 1824 to the winter of 1825.89 As a nonmember participant who spoke impromptu during Methodist meetings, he would have received little or no formal rhetorical training compared to that available to exhorters with complete membership.90 Turner also reported:

Joseph had a little ambition; and some very laudable aspirations; the mother’s intellect occasionally shone out in him [Page 284]feebly, especially when he used to help us solve some portentous questions of moral or political ethics, in our juvenile debating club, which we moved down to the old red school house on Durfee street.91

Here, Turner described Smith as a capable debater but attributes the skill to his “mother’s intellect” when it “shone out in him feebly.” Overall, he seemed less impressed with the youthful Joseph: “He was lounging, idle; (not to say vicious,) and possessed of less than ordinary intellect. The author’s own recollections of him are distinct ones.”92

Richard Bushman observed that Joseph Smith “is not known to have preached a single sermon before organizing the church in 1830.”93 He had no reputation as a preacher. James Gordon Bennett recorded that Joseph Smith’s father was a “grand story teller,” but wrote nothing similar concerning the younger Joseph.94

Other references to Joseph Smith’s oratory skills before and after the Book of Mormon dictation are varied. Jared Carter remembered him in the early 1830s as “not naturally talented for a speaker.”95 An unidentified critic from Henrietta, New York, described him in 1834: “His manner is ungainly, his diction coarse, and his delivery slow and labored. There is nothing in his appearance or language to excite much attention.”96

[Page 285]Peter H. Burnett, who had served as Joseph Smith’s lawyer in Missouri and later governor of California, recalled:

His appearance was not prepossessing, and his conversational powers were but ordinary. You could see at a glance that his education was very limited. He was an awkward but vehement speaker. In conversation he was slow, and used too many words to express his ideas, and would not generally go directly to a point.97

In 1886, Sarah Pratt recalled:

Joseph did not talk much in society, his talk was not very fluent. He used to make a remark now and then, letting the others talk. Whenever he spoke of Church affairs, his talk grew intelligent. He had no great choice of words, and generally expressed his ideas in a very humble, common-place way. . . . Joseph was no orator. He said what he wanted to say in a very blundering sort of way.98

This review of Joseph Smith’s documentable skills should not be interpreted as evidence he was dumb or cognitively challenged. Joseph was intelligent, but this data show that in 1829, he was not proficient in any of the aptitudes AI chatbots predicted would be needed to dictate the Book of Mormon using only an author’s intellect.

AI fail: Inability to document Joseph Smith possessed the fifteen skills

Although the fifteen skills identified by AI appear to be reasonable and valid, historical accounts indicate Joseph Smith did not possess them in 1829. These observations indicate that Artificial Intelligence has failed in this application. However, the reasons for failure are not empirically obvious.

[Page 286]Identifying Two Historically Defensible Lists of Joseph Smith’s 1829 Skills

Two contradictory but historically defensible lists of Joseph Smith’s 1829 skills emerge from the discussion above.

Joseph Smith dictated the words therefore he possessed the skills

Multiple eyewitness accounts describe how Joseph Smith spoke all 269,320 words of the 1830 Book of Mormon. Employing this fact and the Latin phrase res ipsa loquitur, which means: “The thing speaks for itself,” logical reasoning supports he did it; therefore, he had the skills.

Fawn Brodie employed this approach: “There is no doubt . . . that Joseph had developed a remarkable facility for dictation. The speed was not ‘far beyond his natural ability;’ it was evidence of his ability.”99 Robert M. Bowman Jr. agreed: “As a matter of historical inquiry, the proper question to ask is not how Joseph Smith could have written the Book of Mormon but rather whether the evidence shows that he did so.”100 This approach circumvents the need to dive further into the historical record, substituting deductive argument for documentation. Accordingly, answering “What skills were needed?” simultaneously answers “What skills did Joseph Smith possess in 1829?”

Eyewitness statements declare Joseph Smith did not have the skills

A second list of Joseph Smith’s 1829 skills is derived from eyewitness accounts describing his capabilities at the time of the dictation of the Book of Mormon. As shown above, this approach fails to historically document any of the skills selected by the AI modules to any significant degree. This database of eyewitness statements also acknowledges that no one who knew Joseph personally attributed the words of the Book of Mormon to his abilities or intellect then or anytime thereafter.

Dealing with the two contradictory approaches

Latter-day Saint believers have capitalized on the disconnect between [Page 287]the predicted essential skills and the documentable ones. Hugh B. Brown included these observations in a talk titled “The Profile of a Prophet” in 1955.101 Hugh Nibley expanded on the idea with his 1960s “Book of Mormon Challenge.”102 Other authors have followed this lead in book-length manuscripts.103 However, these discussions included highly devotional content and were easily dismissed by secular scholars examining the origin of the Book of Mormon.

As the dialogue moves forward regarding Joseph Smith’s ability to dictate all 269,320 words, contextualizing it to the skills needed or exhibited, provides essential nuance. If accurate, the fifteen skills identified by the AI chatbots could be helpful. They more precisely define the discrepancies between the skills he should have possessed versus those skills eyewitnesses attributed to him.

Summary

AI chatbots can produce data as a starting point for task-skills inquiries, but experts must validate such results. When AI chatbots are asked specifically about the skills needed to dictate a book like the Book of Mormon, a generalized list of fifteen skills is generated. According to several criteria, that list accurately predicts the composition and oratory skills an author would need. However, the historical record fails to corroborate that Joseph Smith possessed them in 1829, suggesting a need for additional research. As Robert N. Hullinger observes: “Even if one believes that Joseph Smith was at best a scoundrel, one still must account for the Book of Mormon.”104 Possibly, the greatest usefulness of the AI responses is that they provide a new tool to assist investigators in evaluating how Joseph Smith produced all the words.

[Page 288]Appendix A:

College-Level Vocabulary Words Missing from the Bible

The Book of Mormon includes dozens of vocabulary words not found in the Bible but rated at a college-level difficulty by modern standards.105 Table 3 lists sophisticated words used in the Book of Mormon but absent from the KJV Bible and seldom found in other popular books of the day.106 Word difficulty is scaled from 1 (low) to 10 (high). The abbreviation “n/a” signifies no data available.

Table 3. Comparison of occurrences of sophisticated words used in the Book of Mormon, Bible, and selected 1820s books.

| Words found in the Book of Mormon | Difficulty | Book of Mormon | KJV Bible | English Reader |  |

|

The Late War |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| arraigned | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| derangement | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ignominious | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| scantiness | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| breastwork | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| priestcraft | 10 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [Page 289]abridgment | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cimeter [scimitar] | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| indolent | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| insensibility | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| interposition | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| typifying | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| condescension | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| stratagem | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| depravity | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| discernible | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| enumerated | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| frenzied | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| impenetrable | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| iniquitous | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| repugnant | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| serviceable | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| abhorrence | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nothingness | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| flaxen | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| embassy | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| probationary | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| hinderment | n/a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| overbearance | n/a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| consignation | n/a | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| unwearyingness | n/a | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

An additional sixty-nine words occur only once in the Book of Mormon and are not found in the KJV Bible (with vocabulary difficulty score in parentheses):107

[Page 290]aggravating (7), appellation (9), apprised (9), astonishing (6), awkwardness (9), baseness (10), beggars (8), beguile (10), bliss (6), brazen (8), captivation (9), censured (8), coarseness (10), confounding (8), consecrating (9), consign (9), deformed (7), disowned (9), dispelled (8), dissenter (10), divulge (7), dormant (6), droop (9), earnestness (6), enact (6), engulf (9), exert (6), exhausting (7), exult (9), faction (6), frailties (9), garb (7), glimmer (7), havoc (6), incomprehensible (7), indolence (10), inexpressible (10), infancy (6), infirm (8), infused (8), insensibility (9), insurrections (8), intrigues (7), lonesome (8), massacre (6), misunderstand (8), monarchy (6), observance (6), perversion (8), pester (9), plunged (6), precarious (7), recollection (7), redoubled (9), relinquished (7), reluctance (6), reunite (8), scoffing (9), slackened (10), sprouted (8), stupor (9), subsistence (6), trifle (8), triumphant (7), tyrant (7), undaunted (9), unsteadiness (10), victorious (7), and wilfulness (10).

Similarly, the twenty-seven words below are used only once in the Book of Mormon and three times or less in the 783,137-word KJV Bible (vocabulary difficulty in parentheses):

austere (8), avenging (8), babblings (8), banished (8), barbarous (9), barbarous (9), canker (9), conquerors (9), daunted (10), extolled (9), fain (9), foretold (9), garners (7), gnash (10), grudgingly (9), moisture (4), nurture (6), overshadow (9), overspread (10), orphans (6), providence (7), solemnity (9), tarrying (9), thicket (9), weariness (8), zealously (8), and wrestle (7).

Words appearing even once require the same vocabulary training and skill as words used dozens of times. “Both practice and repeated encounters with words seem to be important for the acquisition of vocabulary,” observe Elfrieda H. Hiebert and Michael L. Kamil in their book, Teaching and Learning Vocabulary.108

[Page 291]Appendix B:

Documentary Evidence and Visions in a Seer Stone

In his book Visions in a Seer Stone, William L. Davis introduces a theory that attributes remarkable sermon-composition skills to Joseph Smith in 1829. It describes those abilities as emanating from his natural intellect but does not entirely discount the possibility of divine assistance.109

Joseph Smith’s alleged 1829 skill of “laying down heads”

William L. Davis asserts that in 1829 Joseph Smith possessed a highly developed skill of “laying down heads,” or the ability to create, memorize, recall, and spontaneously expand (vocally) outlines of the content to be communicated. However, the supportive evidence for this claim is sparse and problematic.

The primary corroborating documentation presented in Visions in a Seer Stone is Joseph’s 1832 History.110 Davis reports: “Smith’s 1832 history begins with an opening paragraph that provides the reader with a sketch outline of the historical events that Smith wished to emphasize in his narrative.”111 Davis further explains:

Smith’s method of using a preliminary outline, or, as more commonly termed, a “skeleton” of “heads” (an outline formed with key summarizing phrases) to organize and arrange his 1832 historical narrative, was a standard technique of composition in the early nineteenth century. The explicit use of the skeletal sketch in the opening of the history, marking each stage in the sequence of the narrative with a summarizing phrase, provides one of several expressions of the method commonly known as “laying down heads.”112

Davis refers to the 1832 History more than forty times in Visions in a Seer Stone as evidence of Joseph Smith’s proficiency in laying down heads.113 Additionally, the 1832 History is portrayed as an example of the technique and a manifestation of Joseph’s “personal method and style of composition.”114

[Page 292]Examining Joseph Smith’s 1832 History

Nine subjects or “headings” can be identified in the 173-word opening paragraph of Joseph Smith’s 1832 History (in bold brackets):

[1] A History of the life of Joseph Smith Jr. [2] an account of his marvilous experience and [3] of all the mighty acts which he doeth in the name of Jesus Ch[r]ist the son of the living God of whom he beareth record and also [4] an account of the rise of the church of Christ in the eve of time according as the Lord brought forth and established by his hand [5] <firstly> he receiving the testamony from on high [6] seccondly the ministering of Angels [7] thirdly the reception of the holy Priesthood by the ministring of—Aangels to adminster the letter of the Law <Gospel—> <—the Law and commandments as they were given unto him—> and in <the> ordinencs, [8] forthly a confirmation and reception of the high Priesthood after the holy order of the son of the living God power and ordinence from on high to preach the Gospel in the administration and [9] demonstration of the spirit the Kees of the Kingdom of God confered upon him and the continuation of the blessings of God to him &c——

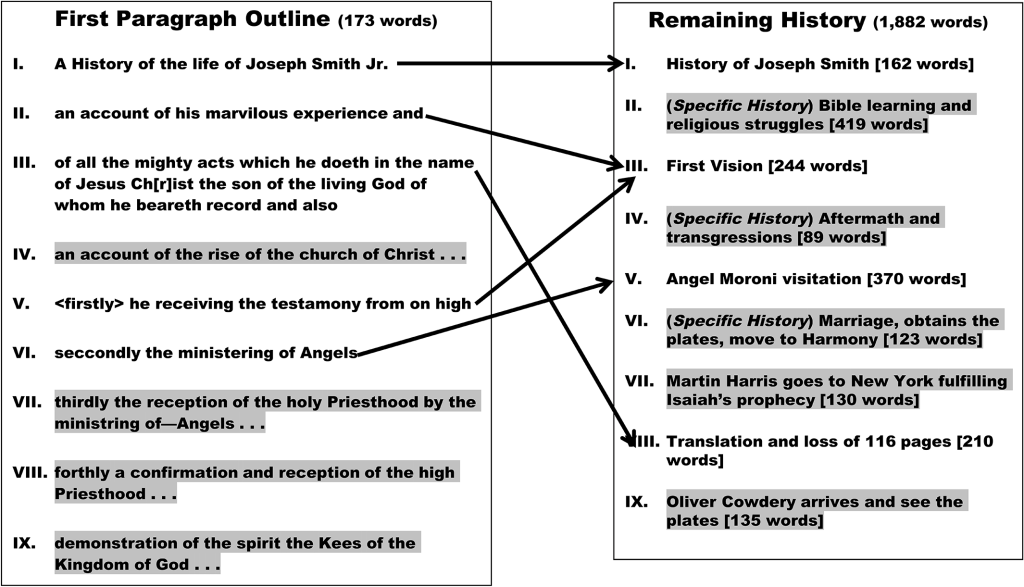

However, the nine outlined topics do not correlate well with the subjects covered in the ensuing 1,882-word account (see figure 1).

For the “laid down” headings in the opening skeleton outline to be helpful to the speaker, they must be appropriately sequenced and sufficiently specific to guide the ensuing speech. This does not occur in this example. For example, several headings are not covered: “an account of the rise of the church . . .,” “thirdly . . .,” “fourthly . . .,” and “demonstrations of . . . .” Some of these hanging headings could result from Joseph Smith’s inability to complete the manuscript as he originally intended.

However, a more significant disconnect becomes apparent as multiple topics in the remaining narrative are not predicted in the first paragraph, including his Bible learning and religious struggles, the aftermath of the First Vision and his transgressions, his marriage and move to Harmony, Martin Harris’s journey to New York, or Oliver Cowdery’s arrival. These mini-storylines comprise nearly half the remaining account but are not forecasted in any specific way in the outline headings. The order of presentation also reflects inconsistencies.

[Page 293]

Figure 1. Diagram showing that the first paragraph outline (left) contains nine headings that correspond poorly to the headings of topics discussed in the remaining 1,882-word history (right). Items in gray are not addressed.

Handwriting analysis shows that Joseph Smith wrote 1,013 words of the 1832 History and dictated the other 1,043 words to his scribe, Frederick G. Williams, who wrote most of the first paragraph.115 The divergences between the outline paragraph and the ensuing content raise the question of why Joseph didn’t simply follow the written outline by referring back to it. It appears that strictly following the original outline was not his intent.

These observations demonstrate that Joseph Smith’s 1832 History does not corroborate Davis’s assertions that Joseph possessed expertise in laying down heads in 1829. Instead, the opening paragraph and subsequent narration contradict that conclusion, supporting he was either unfamiliar or inexperienced with that preaching style.

Supplementary evidence from late problematic sources

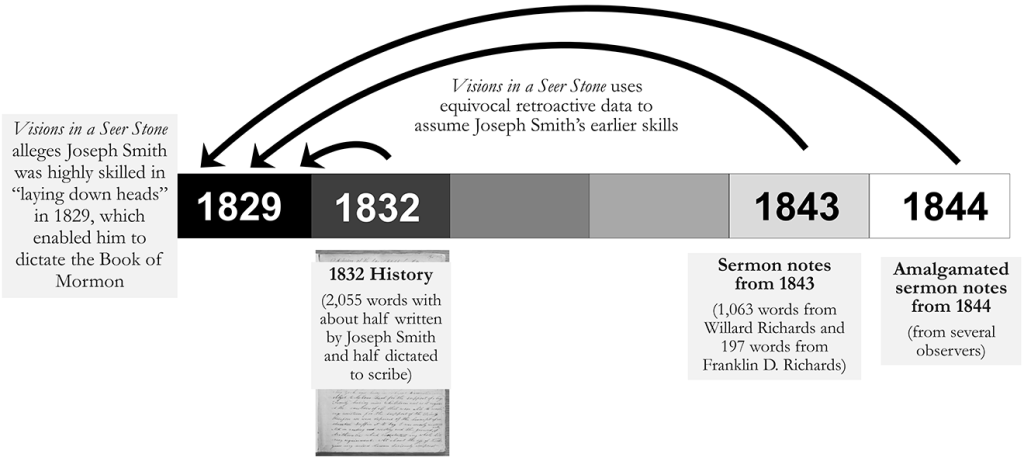

To bolster his theory, Davis also discusses two Nauvoo-era discourses. The importance of the fourteen and fifteen-year gaps between the evidence and the event it seeks to corroborate is minimized (see figure 2). Additional problems stem from the fact that the discourses were not recorded verbatim. Hence, the notes recorded reflect the style of the listener in each instance.

[Page 294]

Figure 2. Visions in a Seer Stone seeks to document Joseph Smith’s 1829 skills from a very small sampling, all from years afterward. Multiple additional problems can be identified (see discussion in text).

Visions in a Seer Stone draws detailed conclusions regarding Joseph Smith’s 1829 skills from very small narrative samples. It also assumes that the skills existed retroactively and fails to address the possibility that they may have been learned after 1829.

It could be argued that the notes from listeners to Joseph Smith’s discourses over a decade after dictating the Book of Mormon have minimal direct application to his 1829 abilities. He demonstrably learned new skills in the interim.

Undocumented skills in Visions in a Seer Stone

As noted in this paper, Visions in a Seer Stone also portrays Joseph Smith exhibiting many of the other skills listed by the AI chatbots. However, Davis presents little or no historical documentation to verify Joseph acquired them before 1829. Instead, by assuming the Book of Mormon flowed from Joseph Smith’s intellect, Davis repeatedly uses its content as evidence of Smith’s 1829 skillset. The resulting conclusions are based on circular logic and are less convincing. A second approach assumes that Joseph picked up skills through environmental influences without documenting that he did. Table 4 summarizes the assumed skills.

[Page 295]Table 4. Sources of evidence presented in Visions in a Seer Stone to document Joseph Smith’s assumed 1829 skills. High correlation is ++++.

| AI-generated list of skills needed to dictate a book with characteristics of the Book of Mormon | Source of evidence cited in Visions in a Seer Stone | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assumptions based on Book of Mormon text | Assumptions based on environmental influences | Historical accounts of Joseph Smith’s 1829 abilities | |

| Attention to detail | ++++ | ++ | + |

| Bible and theology | ++ | ++++ | + |

| Creativity-imagination | ++++ | + | – |

| Discipline-stamina | – | – | – |

| Editing | +++ | + | – |

| Memory | ++++ | ++++ | – |

| Mental focus | – | + | – |

| Organizational | ++++ | ++ | – |

| Religious composition | +++ | ++++ | – |

| Research-specialized knowledge | +++ | +++ | – |

| Speaking—dictation | +++ | ++++ | + |

| Storytelling | +++ | ++++ | + |

| Time management | – | – | – |

| Vocabulary-language | ++++ | ++++ | – |

| World-building | – | – | – |

Summary

Visions in a Seer Stone is a significant contribution to Book of Mormon studies because it approaches Joseph Smith’s 1829 dictation in terms of the literary skills he would have needed (and ostensibly possessed) to accomplish it. However, the primary evidence presented to support the skill discussed—“laying down heads”—is his 1832 History. It contains multiple disconnects between the headings outlined in the opening paragraph and those discussed in the remaining narrative. At best, it might represent a beginner’s attempt to harness the power of laying down heads, but shows little or no proficiency with the process. Visions in a Seer Stone also quotes observations on discourses delivered more than a decade afterward. But such provide minimal additional persuasiveness.

[Page 296]Lastly, Visions in a Seer Stone portrays Joseph Smith exhibiting at least twelve AI-generated skills during the dictation, even though it does not openly acknowledge that such skills would have been needed. In so doing, it tacitly validates those chatbot responses. Most of these additional abilities are not corroborated historically. Instead, assumptions based on textual observations and environmental influences consistently substitute for documented evidence of Joseph Smith’s 1829 skills.

Go here to see the 4 thoughts on ““What Can Artificial Intelligence Tell Us About the Literary Skills Needed to Dictate a Text Like the Book of Mormon?”” or to comment on it.