[Page 183]Abstract: Grant H. Palmer, former LDS seminary instructor turned critic, has recently posted an essay, “Sexual Allegations against Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Polygamy in Nauvoo,” on MormonThink.com. In it, Palmer isolates ten interactions between women and Joseph Smith that Palmer alleges were inappropriate and, “have at least some plausibility of being true.” In this paper, Palmer’s analysis of these ten interactions is reviewed, revealing how poorly Palmer has represented the historical data by advancing factual inaccuracies, quoting sources without establishing their credibility, ignoring contradictory evidences, and manifesting superficial research techniques that fail to account for the latest scholarship on the topics he is discussing. Other accusations put forth by Palmer are also evaluated for correctness, showing, once again, his propensity for inadequate scholarship.

Sometime after 1999, Grant Palmer outlined his views on Joseph Smith and plural marriage up to 1835.1 More recently, he has expanded that paper and retitled it: “Sexual Allegations against Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Polygamy in Nauvoo.” His newer work contains the same material as the former essay, with added observations and allegations.

[Page 184]Recently Palmer posted the article on MormonThink, a website that is primarily antagonistic to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and reportedly submitted it for consideration to a scholarly journal.2 This essay will examine both the accepted methodology Palmer consistently neglects to employ and the errors in his analysis, which following scholarly standards could have prevented.

Weaknesses of Grant Palmer’s Methodology

Throughout Palmer’s essay, several problematic issues can be readily discerned:

1. Factual inaccuracies. For example, on page 8 he speaks of a man, “Benjamin F. Winchester,” but there is no such person. Church history participants included “Benjamin F. Johnson” and “Benjamin Winchester” but no “Benjamin F. Winchester.” This might seem a nitpicky criticism, but it is an example of how poorly Palmer’s essay has been constructed and edited. It also suggests a reliance on secondary sources rather than a consultation of the original documents.3

2. Quoting historical sources without establishing credibility of the documents. Palmer is willing to quote just about any source so long as it conveys the message he desires. Whether his source is reliable is apparently a non-issue. In this, Palmer resembles hardened anti-Mormons or uncritical apologists, both of whom are often willing to quote any persuasive voice if it reinforces their predetermined message.

[Page 185]3. Ignoring contradictory evidence. Palmer is entitled to his opinion of Joseph Smith and plural marriage. However, good scholarship requires authors to consider and address all of the evidence, even those sources that contradict the writer’s agenda. Palmer carefully ignores all contradictory evidence, but he does so at the peril of appearing overly biased and agenda-driven.

4. Ignoring the most recent scholarship. In 2013, Greg Kofford Books published Brian Hales’s three volume work Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology. With over 1500 pages, it aims to either reference or quote every known document dealing with Joseph Smith’s polygamy. Palmer references these volumes only once, in footnote 34. A single mention in itself is not necessarily problematic. But in dealing with the individual topics in his essay, Palmer routinely ignores pertinent historical manuscripts that are discussed in those volumes and plainly identified in the bibliography. Thus, Palmer either did not read or understand a work that he cites, or he chooses to hide important details from his readers. Even if Hales’s conclusions are in error, these new publications contain data, which Palmer must address if he is to be credible.

Joseph Smith’s Reasons for Establishing Plural Marriage

Palmer begins by asking why Joseph Smith established plural marriage. He acknowledges one reason, as part of a “restitution of all things” (Acts 3:21), which restoration is mentioned in Doctrine and Covenants 132:40, 45. While Palmer is to be commended for mentioning the revelation three times in his essay, he fails to discuss the primary reason for plural marriage in Joseph Smith’s theology. Verse 17 explains the need for all the righteous to be sealed to an eternal spouse, otherwise they “remain separately and singly, without exaltation, in their saved condition, to all eternity.” Verse 63 likewise says that plural marriage is intended “for their exaltation in the eternal worlds.” Unsurprisingly, Palmer completely ignores this nonsexual dimension to Joseph’s theology of plurality, even though it deals with eternity and eternal rewards rather than [Page 186]earthly aspects of plurality. Within Joseph Smith’s teachings there is more emphasis on eternal matters than on the sexual desire to which Palmer directs our attention.

Following the tradition of Mormon fundamentalists today, Palmer writes: “Joseph Smith taught, ‘No one can reject this covenant [polygamy] and be permitted to enter into my glory. For all … must and shall abide the law, or he shall be damned, saith the Lord God’” (p. 1). Palmer is quoting a portion of D&C 132:19, though the addition of the bracketed word is misleading. Typically, such textual emendations are intended to add clarity to a citation. In this case, however, it is not clear upon what Palmer bases his gloss, save his own opinion, since he provides no documentation to support it. If an emendation is not patently obvious from elsewhere in the source text, the author has a duty to justify his reading or risk distorting his source.

Unfortunately for his reconstruction and his readers, Palmer’s bracketed commentary “[polygamy]” contradicts the first line of the verse, which promises exaltation to a worthy monogamous couple who are sealed by proper authority. “If a man marry a wife” (D&C 132:19, italics added) clearly refers to a single worthy man being sealed to a single worthy wife by proper authority. Such sealed couples “shall pass by the angels, and the gods, which are set there, to their exaltation and glory.” Nineteenth century leaders certainly understood that “a Man may Embrace the Law of Celestial Marriage in his heart & not take the Second wife & be justified before the Lord.”4 This calls Palmer’s interpretation into question.

In Part 1 of this review, we will consider Palmer’s ten claims of Joseph Smith’s alleged extra-marital sexual encounters. In Part 2, we will examine related claims and historical missteps that Palmer makes as he strives, but fails, to establish his thesis.

[Page 187]

Part 1 — Ten Claims of Alleged “Sexual Encounters”

Palmer alleges that Joseph may have confessed to “sexual encounters” (p. 4). He selectively quotes Joseph’s official account in an effort to reinforce this impression for his readers:5

I was left to all kinds of temptations, and mingling with all kinds of society, I frequently fell into many foolish errors and displayed the weakness of youth and the corruption of human nature, which I am sorry to say led me into divers temptations, to the gratification of many appetites offensive in the sight of God.6

Palmer then asks: “Could the ‘gratification of many appetites’ refer to sexual encounters with women?” (p. 4). Curiously, Palmer quotes Joseph’s answer, but hides it in footnote 7. Apparently, after publishing the quotation above, the Prophet anticipated allegations like Palmer’s, so in December 1842 he dictated an addition that permits no misunderstanding:

In making this confession, no one need suppose me guilty of any great or malignant sins: a disposition to commit such was never in my nature; but I was guilty of Levity, & sometimes associated with jovial company &c, not Consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as I had been; but this will not seem very strange to any one who recollects my youth & is acquainted with my native cheerly [sic] Temperament.7

[Page 188]Lest Palmer assume that this addition was a late attempt to cover having revealed too much, we note that Joseph made essentially the same clarification to Oliver Cowdery in 1834:

During this time, as is common to most, or all youths, I fell into many vices and follies; but as my accusers are, and have been forward to accuse me of being guilty of gross and outrageous violations of the peace and good order of the community, I take the occasion to remark, that, though, as I have said above, “as is common to most, or all youths, I fell into many vices and follies,” I have not, neither can it be sustained, in truth, been guilty of wronging or injuring any man or society of men; and those imperfections to which I allude, and for which I have often had occasion to lament, were a light, and too often, vain mind, exhibiting a foolish and trifling conversation.

This being all, and the worst, that my accusers can substantiate against my moral character, I wish to add, that it is not without a deep feeling of regret that I am thus called upon in answer to my own conscience, to fulfill a duty I owe to myself, as well as to the cause of truth, in making this public confession of my former uncircumspect walk, and unchaste conversation: and more particularly, as I often acted in violation of those holy precepts which I knew came from God. But as the “Articles and Covenants” of this church are plain upon this particular point, I do not deem it important to proceed further. I only add, that (I do not, nor never have, pretended to be any other than a man “subject to passion,” and liable, without the assisting grace of the Savior, to deviate from that perfect path in which all men are commanded to walk!)8

[Page 189]One of the more remarkable statements in Palmer’s article is on page three: “it is generally unknown that he [Joseph Smith] was accused of illicit sexual conduct with a number of women from 1827 on, until his death in 1844.” One must ask if this observation remains “generally unknown” because there is scant supporting evidence or for some other reason.

Palmer discusses ten allegations that, according to his research, “have at least some plausibility of being true”:

Sexual claims made against his [Joseph Smith’s] character began only after he was married in January 1827. From 1827–1841, a number of sexual allegations are leveled against Smith, several of which I think contain so little information they are not worth mentioning. This section of the article [the following ten accounts] concentrates on the declarations that have at least some plausibility of being true. (p. 5)

Surprisingly, Palmer seems unaware — or unconcerned — that available contemporaneous evidence does not support his assertion. That is, there is at most one accusation of “illicit sexual conduct” (p. 3) (case #2 below). As explored below, this claim was made in an off-handed manner, and it was not echoed by those who could have confirmed it. After one mention, it did not resurface until decades after Joseph’s death.

We will see that Palmer’s other “evidences” (p. 28) are all likewise problematic and dubious on multiple other grounds, and they were all made after Joseph’s death.

Given that novel religious groups were often charged with sexual deviancy,9 regardless of their actual conduct, it is astonishing that Joseph Smith was not so accused simply as a matter of course. Had there been even a hint of such scandal, Joseph’s enemies would have pounced upon it. The virtual silence is a telling clue that Joseph was not seen as lecherous by [Page 190]his contemporaries until the doctrine of plural marriage was taught.

#1: Broome County Trial

Palmer’s first “declaration” of Joseph Smith’s sexual impropriety is associated with a trial in South Bainbridge, Broome County, New York (p. 5). The Prophet was arrested on 30 June 1830 and was tried the following day. Twelve witnesses were called, including Miriam and Rhoda Stowell. No trial records are extant.

Twelve years later Joseph recalled the trial and claimed that nothing was found against him: “The young women arrived and were severally examined, touching my character, and conduct in general but particularly as to my behavior towards them both in public and private, when they both bore such testimony in my favor, as left my enemies without a pretext on their account.”10 His recollection was fully corroborated in 1844 when John S. Reed — his non-Mormon attorney for the case — visited Nauvoo. Reed recalled: “Let me say to you that not one blemish nor spot was found against his character; he came from that trial, notwithstanding the mighty efforts that were made to convict him of crime by his vigilant persecutors, with his character unstained by even the appearance of guilt.”11

To summarize, Joseph was tried on charges unrelated to immorality and all accounts state he was not guilty of anything improper. Had sexual liberties been proven or even seemed plausible, contemporary anti-Mormon authors would have surely used such damning material against Joseph.

Nothing in these accounts appears to support “illicit sexual conduct.” Palmer could speculate about the reasons for the girls’ testimony and then criticize Joseph based on his speculations, but this would not be evidence.

[Page 191]

#2: Eliza Winters

Palmer’s second bit of evidence is an incident that reportedly occurred between October 1825 and June 1829, involving a woman named Eliza Winters. Testimony of the described interaction was not recorded until 1834. Palmer writes:

When Joseph and his wife Emma Hale Smith were living in Harmony in 1827–1829, Emma’s cousin, Levi Lewis, accused him of attempting “to seduce Eliza Winters,” Emma’s close friend.12 Lewis further said that he was well “acquainted with Joseph Smith Jr. and Martin Harris, and that he has heard them both say, [that] adultery was no crime. Harris said he did not blame Smith for his attempt to seduce Eliza Winters” (p. 6).13

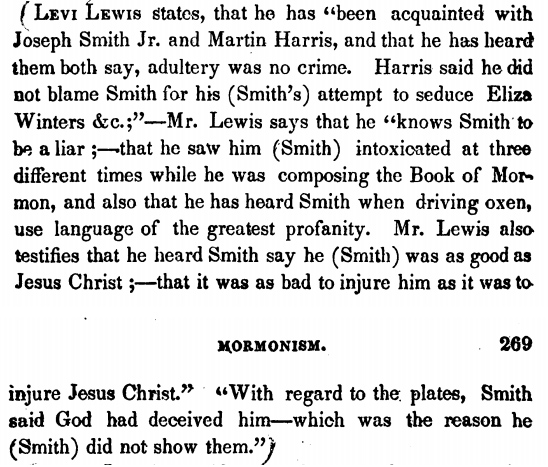

Palmer’s presentation of the evidence is curious, if not deceptive. He states: “Levi Lewis, accused him [Joseph Smith] of attempting ‘to seduce Eliza Winters,’” and then he quotes a longer sentence containing the same quoted words as if they were separate allegation, when in fact he is just re-quoting the same sentence (see Figure 1, top of next page).

Importantly, Palmer misrepresented the quotation. According to the published version, Levi Lewis did not accuse Joseph Smith from direct personal knowledge — he does not provide us with a first-hand allegation. Instead, we read that Lewis was allegedly quoting Martin Harris. Palmer deftly transforms a dubious second-hand or third-hand account into a first-hand allegation.

There is much in this account that should make us doubt its accuracy.

[Page 192]

Figure 1: Levi Lewis affidavit citation in E.D. Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed (1834)14

First, it seems unlikely that Martin Harris would have remained devoted to Joseph Smith as a missionary in the 1830s if he were aware of such hypocritical and immoral behavior. Joseph taught that sexual immorality was a sin next to murder in severity (Alma 39:5).15

[Page 193]Second, Eliza Winters never referred to a seduction attempt by Joseph Smith. Despite having at least two perfect opportunities to corroborate Lewis’s allegations, she failed to do so.

The first opportunity occurred in 1833 when Martin Harris accused her of having given birth to a “bastard child.” (That Martin regarded this as a damning accusation makes it even less likely that he would tolerate a dalliance by Joseph as Levi Lewis claimed.) Eliza retaliated by suing Martin in court.16 Throughout the proceedings, no one, including Eliza herself, mentioned a seduction attempt by Joseph, and the case was ultimately dismissed due to jurisdictional problems.

The second opportunity for Eliza to confirm Lewis’s charge occurred nearly fifty years later. Newspaperman Frederick G. Mather interviewed the seventy-year-old Eliza in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, specifically to gather derogatory statements about the Prophet from his former acquaintances. In the interview, Mather recorded Eliza saying, “Joe Smith never made a convert at Susquehanna, and also that his father-in-law became so incensed by his conduct that he threatened to shoot him if he ever returned.”17 Notwithstanding her critical attitude toward Joseph and the church he founded, Eliza did not make any accusation regarding Joseph’s personal conduct toward her or other women. Her failure to incriminate the Prophet is puzzling if the Lewis allegations were true.18

[Page 194]A third reason to doubt Levi Lewis’s account is silence from other sources. Lewis was Emma Hale Smith’s cousin, and he provided his affidavit as part of the collection amassed by Doctor Philastus Hurlbut19 and published by Eber D. Howe in the first anti-Mormon book.20 The following members of Lewis’s family also provided affidavits to Hurlbut and Howe:

- Isaac Hale (Emma’s father),

- Alva Hale (Emma’s brother),

- Nathaniel Lewis (Emma’s uncle, a Methodist preacher), and

- Sophia Lewis (wife of Levi).21

These testators were quick to condemn Joseph for eloping with Emma Smith, yet they remain utterly silent on the matter of Joseph’s supposed adulterous conduct. They would have been witnesses in the same sense as Levi was — he could only repeat information supposedly gained from a third party. Despite their interest in condemning Joseph, these other family members made no mention of Joseph’s alleged conduct, even as a matter of rumor.

A fourth reason to doubt Lewis arises from falsehoods or implausibilities in the rest of his testimony. If he perjures himself on these points, then he is a less convincing witness in other matters. We do not have the original affidavit, but the published version includes the following claims:

- he heard Joseph admit that “God had deceived him” about the plates, so did not show them to anyone,

- [Page 195]he heard Joseph say “he … was as good as Jesus Christ; … it was as bad to injure him as it was to injure Jesus Christ,” and

- he saw Joseph drunk three times while writing the Book of Mormon.22

These claims simply do not hold water. Far from denying that he had shown anyone else the plates, Joseph insisted that he had and published the testimonies of eleven witnesses in every copy of the Book of Mormon. Levi’s honesty is questionable if he can blithely ignore what any Book of Mormon reader can easily discover.

A study of Joseph’s letters and life from this period makes it difficult to believe that Joseph would insist he was “as good as Jesus Christ.”23 Joseph’s private letters reveal him to be devout, sincere, and almost painfully aware of his dependence on God.24

The claim to have seen Joseph drunk during the translation is entertaining. If Joseph were drunk, it would make the production of the Book of Mormon more impressive. The charge sounds like little more than idle gossip designed to bias readers against Joseph as a “drunkard.”25

In sum, when all the evidence is examined, this report of an “attempted” seduction appears unconvincing and implausible. Palmer’s audience, however, will learn none of these facts.

[Page 196]

#3: Marinda Nancy Johnson

Palmer’s third “declaration” involves Marinda Nancy Johnson in conjunction with the 1832 tar and feathering of the Prophet and Sidney Rigdon (p. 7). Luke Johnson, who was not present but knew some of the participants, published this account in 1864:

In the fall of [1832], while Joseph was yet at my father’s [John Johnson’s home], a mob of forty or fifty came to his house, a few entered his room in the middle of the night, and Carnot Mason dragged Joseph out of bed by the hair of his head; he was then seized by as many as could get hold of him, and taken about forty rods from the house, stretched on a board, and tantalized in the most insulting and brutal manner; they tore off the few night clothes that he had on, for the purpose of emasculating him, and had Dr. Dennison there to perform the operation; but when the Dr. saw the Prophet stripped and stretched on the plank, his heart failed him, and he refused to operate.26

If these events were triggered in part by sexual crimes against Marinda, it is strange that Luke — her brother — was neither incensed by them, nor even mentioned them.

Concerning Luke Johnson’s account, Palmer claims in his paper:

Eli Johnson was more specific. He was troubled because Smith and Rigdon were urging his brother John Johnson to “let them have his property,”27 and was “furious because he suspected Joseph of being intimate with his sister [actually she was his sixteen year old niece], Nancy Marinda Johnson, and he was screaming for Joseph’s castration.”28 (p. 8)

[Page 197]

Figure 2: Drawing by unknown artist, published in Charles Mackay, ed., The Mormons, or Latter-day Saints; with Memoirs of the Life and Death of Joseph Smith, the American Mahomet, 4th ed. (London: Office of the National Illustrated Library, 1851), 55; 1851 edition in Hales’s possession.

Palmer’s willingness to detail Eli Johnson’s feelings is remarkable because there is no known report from Eli. At best Palmer is extrapolating, at worst he is mindreading.29

It is probable that Palmer’s commentary is ultimately based upon a late, second-hand reference from Clark Braden, a

[Page 198]

Figure 3: Clark Braden30

Church of Christ (Disciples) minister whose religious debates were reputedly free and economical with the facts.31 Braden (b. 1831) was not present in Kirtland in the 1830s, but in a debate with RLDS missionary E. L. Kelly fifty-two years later he stated: “In March 1832, Smith was stopping at Mr. Johnson’s, in Hiram, Ohio, and was mobbed. The mob was led by Eli Johnson, who blamed Smith for being too intimate with his sister Marinda.”32

Importantly, prior to this 1884 claim by a non-participant, all accounts strongly suggest that the mob members were primarily concerned with attempts to live the law of consecration in 1832. For example, “Symonds Rider … clarified” in 1868 that

Rigdon and Smith were not assaulted because of their beliefs. “The people of Hiram were liberal about religion and had not been averse to Mormon teaching,” he said afterwards. What infuriated the evildoers were [Page 199]some official documents they found, possibly a copy of the revelation outlining the “Law of Consecration and Stewardship,” which instructed new converts about “the horrid fact that a plot was laid to take their property from them and place it under the control of Smith.”33

Rigdon’s biographer theorized that Sidney was, in fact, the primary target, since he was attacked first and treated more harshly than Joseph.34 In addition, Marinda recalled in 1877: “I feel like bearing my testimony that during the whole year that Joseph was an inmate of my father’s house I never saw aught in his daily life or conversation to make me doubt his divine mission.”35 If sexual impropriety was an issue in 1832, it is strange that even hostile sources made no mention of it until 1884. It does not appear in the historical record prior to that time.

#4: Vienna Jacques

Palmer continues his list of “declarations” by presenting the case of Vienna Jacques:

While Vienna Jacques was living in Kirtland in 1833, a Mrs. Alexander quoted Polly Beswick as saying:

It was commonly reported, Jo Smith said he had a revelation to lie /with/ Vienna Jacques, who lived in his family. Polly told me, that Emma, Joseph’s wife, told her that Joseph would get up in the middle of the night and go to Vienna’s bed. Polly said Emma would get out of humor, fret and scold and flounce in the harness. Jo would shut himself up in a room and pray for a revelation. When he came [Page 200]out he would claim he had received one and state it to her, and bring her around all right.”36 (p. 9)

Research supports that “Mrs. Warner Alexander” was actually Nancy Maria Smith, daughter of William Smith (no relation to Joseph Smith) and Lydia Calkins Smith, born 1 December 1822.37 She married Justin Alexander on 4 September 1850, at Kirtland, Ohio, making her “Mrs. Justin Alexander” or “Mrs. Nancy Alexander.”38 It is not clear how or when her name was mis-transcribed, but other internal references also corroborate Nancy as the author.39

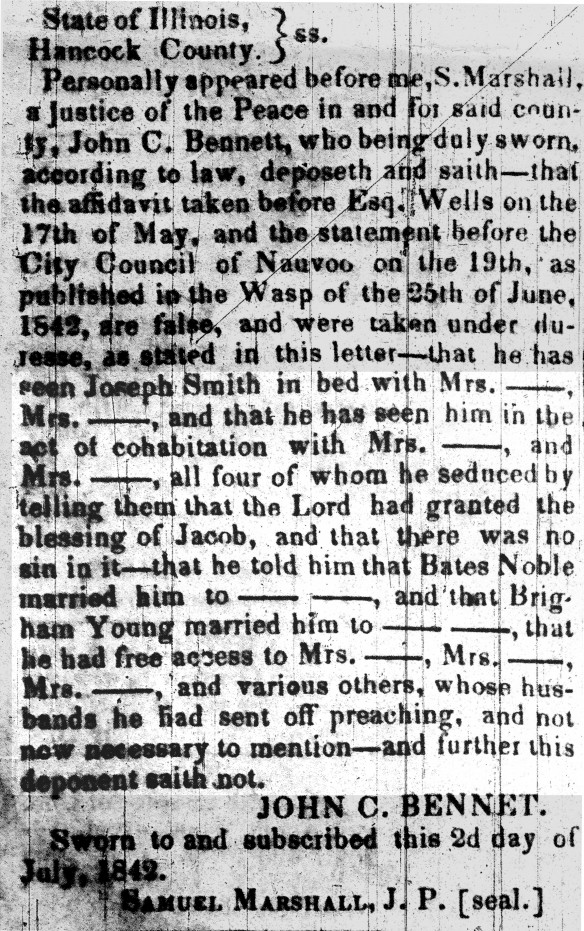

Figure 4: Signature at the bottom of the typed sheet ostensibly quoting Polly Beswick. Hales’s research supports the case for it reading “Mrs Nancy Alexander,” but whether it is her actual signature is unknown.

The historical record shows the Joseph Smith family living around Kirtland, Ohio, from 1831 to 1838. In 1831, Vienna traveled from her home in Boston, Massachusetts, to Kirtland. There she met the Prophet and was baptized. She stayed in Ohio for about six weeks and then rejoined her family in Boston [Page 201]and was instrumental in converting many of them.40 Vienna returned to Kirtland in early 1833 and may have stayed with the Smiths, although we are unaware of any documentation to that effect. On March 8, the Prophet received a revelation telling her to gather to Missouri (D&C 90:28–31). She apparently left in June because he addressed a July 2 letter to her in that state. These two brief periods are the only times during which Vienna and the Smiths lived in the same town.

Accordingly, if Nancy Alexander’s statement is true, in early 1833 Joseph Smith would have needed to accomplish one of two difficult tasks within three or four months. He would have needed to confirm Vienna Jacques’s conversion when she arrived in Kirtland, baptize her, convince her of the doctrine of polygamy and immediately marry her (although the form such a union would take is not known), while also convincing Emma to let him have a plural wife share their home. The second alternative is that Joseph succeeded in seducing the new convert and persuading Emma to allow him to conduct a physical relationship with Vienna (without a plural marriage ceremony) under their roof. Neither proposal seems likely.

As a woman possessing conservative moral values, there [Page 202]is little indication that Emma would have ever approved of her husband having sexual relations outside of marriage. Emma struggled mightily in 1843–1844 to accept plural marriage; it seems a frank affair would have been even more difficult for her in 1833. All records from the Kirtland period demonstrate that she did not then believe that God-approved plural marriage had been restored. Accordingly, she would have considered any polygamous intimacy as adultery and would not have permitted contact between the two as described by Nancy.

Palmer’s brief and uncritical reference to Vienna Jacques is another evidence of his willingness to include any potentially negative account regardless of the narrative’s credibility. One gets the impression that he is simply borrowing any critical material from secondary sources without rigorously evaluating it for his readers.

#5: A “Miss Hill”

Palmer also alleges that Joseph Smith had an inappropriate relationship in Kirtland with a woman called “Miss Hill” in a letter from William McLellin to Joseph Smith III (pp. 9–10). In this 1872 letter, McLellin claimed to reveal facts that he had been told by Emma Smith in 1847:

You will probably remember that I visited your Mother and family in 1847, and held a lengthy conversation with her, retired in the Mansion House in Nauvoo. I did not ask her to tell, but I told her some stories I had heard. And she told me whether I was properly informed. Dr. F. G. Williams practiced with me in Clay Co. Mo. during the latter part of 1838. And he told me that at your birth your father committed an act with a Miss Hill — a hired girl. Emma saw him, and spoke to him. He desisted, but Mrs. Smith refused to be satisfied. He called in Dr. Williams, O. Cowdery, and S. Rigdon to reconcile Emma. But she told them just as the circumstances took place. He found he was caught. He confessed humbly, and begged forgiveness. Emma and all forgave him. She told me this story was [Page 203]true!! Again I told her I heard that one night she missed Joseph and Fanny Alger. she went to the barn and saw him and Fanny in the barn together alone. She looked through a crack and saw the transaction!!! She told me this story too was verily true.41

Predictably, Palmer interprets this letter as recounting two separate stories, one about Joseph Smith’s involvement with “a Miss Hill” and a second regarding a relationship with Fanny Alger (see case #6, below). (One again suspects he may be merely following the lead of one of his secondary sources.42)

Four observations indicate that McLellin was telling only one story and simply became confused.

First, there is no additional evidence that Joseph Smith had a relationship with a woman named “Hill” at Kirtland or at any time in his life. Richard L. Anderson concurs: “I cannot find a possible ‘Miss Hill’ in Kirtland, nor is there any verification of the story.”43

Second, the first part of the paragraph specifies that Emma saw an interaction between Joseph and “a hired girl” identified as “Miss Hill.” In the second half of the same paragraph, McLellin states that Emma “saw him [Joseph] and Fanny in the barn together.” If there were two separate encounters, Emma apparently witnessed them both. McLellin claimed that when Emma learned of the relationship she “refused to be satisfied,” requiring immense efforts from Joseph to assuage her distress. [Page 204]That Joseph would thereafter engage in the same behavior with a second lady, only to be caught yet again by Emma, seems less likely.

Third, an interview three years later between McLellin and anti-Mormon newspaperman J. H. Beadle44 reports only one relationship. Beadle visited Independence, Missouri, in 1875 and reported:

My first call was on Dr. William E. McLellin, whose name you will find in every number of the old Millennial Star, and in many of Smith’s revelations. I found the old gentleman in pleasant quarters. …

He also informed me of the spot [in Kirtland, Ohio] where the first well authenticated case of polygamy took place,45 in which Joseph Smith was “sealed” to the hired girl. The “sealing” took place in a barn on the hay mow, and was witnessed by Mrs. Smith through a crack in the door!46

McLellin’s 1875 story spoke only of one young lady and one relationship. Specifically, he called her “a hired girl” (like “Miss Hill” in the 1872 letter) who was involved with the Prophet “in a barn” (like Fanny Alger in the 1872 letter),47 and the single interaction was witnessed by Emma. Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery hypothesize: “Perhaps, in his old age, William McLellin confused the hired girl, Fanny Alger, with Fanny Hill of John Cleland’s 1749 lewd novel and came up with the hired girl, Miss Hill.”48

Fourth, [Page 205]if McLellin had information on more than one alleged sexual impropriety, it is probable that he would have shared it in other venues than one confusing reference in his 1872 letter. J. H. Beadle would have been elated to include two allegations of Kirtland “sealings” in his published interview with McLellin, especially if both were caught in the act by Emma.

In evaluating all the available evidence, it appears that the accounts consistently refer to one affiliation between Joseph Smith and Fanny Alger in Kirtland in the mid-1830s. The minor variations in the documents are not unexpected in light of the inherent limitations of the historical record. Palmer’s audience will, on the other hand, not learn any of this.

#6: Fanny Alger

Consistent with his overall prejudices, Palmer discusses Joseph Smith’s first plural marriage as if it was an adulterous relationship (pp. 10–11). However, in a 1904 letter Mary Elizabeth Rollins reported: “Joseph the Seer … said God gave him a commandment in 1834, to take other wives besides Emma.”49 Joseph soon complied.

There is strong evidence that this was the Prophet’s first plural marriage. According to the only known account of the circumstances, which comes to us secondhand, Joseph did not approach Fanny directly to discuss a polygamous union. Instead, he enlisted the assistance of his friend Levi Hancock — who was distantly related to Fanny’s family — to serve as an intermediary and officiator. Levi’s son Mosiah wrote in 1896:

Father goes to the Father Samuel Alger — his Father’s Brother in Law and [said] “Samuel the Prophet Joseph loves your Daughter Fanny and wishes her for a wife [Page 206]what say you” — Uncle Sam Says — ”Go and talk to the old woman about it twi’ll be as She says” Father goes to his Sister and said “Clarissy, Brother Joseph the Prophet of the most high God loves Fanny and wishes her for a wife what say you” Said She “go and talk to Fanny it will be all right with me” — Father goes to Fanny and said “Fanny Brother Joseph the Prophet loves you and wishes you for a wife will you be his wife”? “I will Levi” Said She. Father takes Fanny to Joseph and said “Brother Joseph I have been successful in my mission” — Father gave her to Joseph repeating the Ceremony as Joseph repeated to him.50

Eliza R. Snow, who was “well acquainted” with Fanny, also confirmed that a plural marriage occurred when she personally added Fanny’s name to an 1886 list of Joseph Smith’s plural wives.51

As discussed above, Emma discovered the relationship and confronted Joseph. In an effort to placate her, Joseph called on Oliver Cowdery. However, Oliver apparently sided with Emma, likely concluding that the relationship did not constitute a valid union despite the performance of a priesthood ceremony. On 21 January 1838, he wrote to his brother Warren of Joseph’s “dirty, nasty, filthy, scrape.” The word “scrape” is overwritten by “affair.”52 Whether Oliver authorized the change of wording is unknown.

Regarding this first plural marriage, Palmer identifies several “problems” (p. 12):

Palmer: “(1) There is no marriage/sealing ceremony or record of the ordinance.”

[Page 207]Response: Here Palmer demonstrates ignorance of the secrecy surrounding plural ceremonies during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. A few of his sealings can be documented in records written at that time, usually in coded language. For example, Brigham Young’s journal for 6 January 1842 records: “I was taken in to the lodge J Smith was Agness.”53 The second word “was” probably stands for “wed and sealed.”54 However, the vast majority of the Prophet’s sealings were not documented contemporaneously in any way.

As discussed above, Mosiah Hancock provides a second-hand account of a marriage ceremony. Perhaps even more persuasive is the witness of two critics. After she left Joseph and Emma’s home, Fanny would stay with the Chauncey Webb family. Webb would later apostatize from the Church in Utah, and his daughter Ann Eliza Webb would marry Brigham Young, divorce him, and then embark upon a career as an anti-Mormon author and lecturer.

Yet, even though hostile to the Church, both Webb and his daughter referred to Fanny’s plural marriage as a “sealing.”55 The anachronistic use of the term “sealing” by the Webbs during the Utah period to describe a Kirtland-era plural marriage should not be used to imply that Joseph saw his marriage to Fanny as a sealed, “eternal marriage.”56 It does, however, dispel Palmer’s notion that the relationship was a mere dalliance. Eliza Jane also noted that the Alger family “considered it the highest honor to have their daughter adopted into the prophet’s family, and her mother has always claimed that she [Fanny] was sealed [Page 208]to Joseph at that time.”57 This would be a strange attitude to take if their relationship was nothing but a disgraceful affair.

Furthermore, the hostile Webbs had no reason to invent a “sealing” if they knew Fanny was really a case of adultery. The astonishing thing is that they did not think to change the story into an affair or seduction, but they probably thought that a polygamous marriage would be scandalous enough for their audience, as it doubtless was. Their critical account, however, is a valuable clue to how Fanny, her family, and Joseph understood the relationship: as a legitimate, solemnized marriage.

Palmer: “(2) A witness was not present.”

Response: While the Mosiah Hancock account does not list a witness besides his father Levi, it also does not declare there were no witnesses. Less than half of the recollections discussing plural marriages prior to the martyrdom list the names of witnesses. Palmer is making an assumption and then criticizing his assumption, not the historical evidence. Hancock is said to have performed the ceremony, so he serves as a witness of the arrangement — it was formally solemnized, and not simply an adulterous coupling that Joseph later strove to justify as a “marriage” after the fact.

Palmer: “(3) There is no text of a revelation permitting polygamous marriage. Joseph Smith may have talked about polygamy in Kirtland, but there is no evidence that he practiced it until 5 April 1841 at Nauvoo.”

Response: While section 132 was not written until 12 July 1843, multiple evidences document that Joseph learned of the [Page 209]correctness of the principle in 183158 and was commanded to establish the practice in 1834.59 The idea that a revelation had to be written before it could be followed is novel, but inaccurate. The first baptisms for the dead were performed without a written revelation authorizing such ordinances.60

Palmer: “(4) The LDS Church believes Joseph Smith received the keys to “seal” couples for eternity on 3 April 1836 not before.”

Response: We do not claim the Fanny Alger plural marriage was a sealing. Joseph possessed priesthood authority that could solemnize marriages. The first such recorded marriage occurred 24 November 1835, when the Prophet performed the monogamous wedding ceremony of Lydia Goldthwaite Bailey and Newell Knight.61 It is common nowadays to think of plural marriage as always tied to the doctrines of sealing and eternal marriage, but the two concepts are separate. The historical evidence has Joseph discussing plural marriage years prior to expressing ideas about eternal sealings.62

[Page 210]Palmer: “(5) Alger left the state and quickly rejected counsel by marrying a non-Mormon, something one would not expect from a plural wife.”

Response: Fanny Alger told Eliza Jane Webb “her reasons for leaving ‘Sister Emma.’”63 And Andrew Jenson’s notes record that Emma “made such a fuss” about Fanny.64 Palmer is entitled to his opinion, but his supposition of what should be “expected” of a plural wife who had been thrust out of the home by Emma may or may not be valid. Palmer also knows nothing of what “counsel” she received from Joseph, if any. Palmer piles one speculation upon another here to support his theories.

#7: Lucinda Harris

Palmer’s discussion of Lucinda Harris includes a brief statement from Wilhem Wyl’s anti-Mormon work (pp. 12–13).65 Wyl claims that prior to 1886 Sarah Pratt said:

Mrs. [Lucinda Pendleton Morgan] Harris was a married lady, a very good friend of mine. When Joseph had made his dastardly attempt on me, I went to Mrs. Harris to unbosom my grief to her. To my utter astonishment she said, laughing heartily: “How foolish you are! I don’t see anything so horrible in it. Why I am his mistress since four years!”66

Without troubling to evaluate the credibility of either Wyl or Sarah Pratt, Palmer’s shallow scholarship apparently [Page 211]permitted him to cite a brief statement and then move on. However, as witnesses, Sarah Pratt and Wyl are known to have made allegations that can be shown to be blatantly false.67 Both, like Palmer, seemed willing to repeat any rumor so long as it undermined Joseph Smith. Concerning Wyl’s accuracy, non-Mormon writer Thomas Gregg wrote: “The statements of the interviews [in his book] must be taken for what they are worth. While many of them are corroborated elsewhere and [corroborated] in many ways, there are others that need verification, and some that probably exist only in the mind of the narrator.”68 Biographer Richard L. Bushman provided this assessment: “He [Wyl] introduced a lot of hearsay into his account of Joseph. Personally I found all the assertions about the Prophet’s promiscuity pretty feeble. Nothing there [was] worth contending with.”69 Hales has discussed multiple additional problems with the timeline and allegations elsewhere.70

#8: Sarah Pratt

While it may seem unlikely that Grant Palmer’s historical documentation methodology could get any worse, it does. He next quotes from John C. Bennett quoting Sarah Pratt allegedly quoting Joseph Smith (p. 13):

Sister Pratt, the Lord has given you to me as one of my spiritual wives [somewhat like a concubine, or a wife for the night]. I have the blessings of Jacob granted me, as God granted holy men of old, and as I have long looked upon you with favor, and an earnest desire of [Page 212]connubial bliss, I hope you will not repulse or deny me. (p. 13; material in square brackets added by Palmer)

The dramatics in this alleged conversation appear to be Bennett’s elaborations. He refers to “spiritual wifery,” a term Joseph Smith never used except in derision.71 The revelation on celestial and plural marriage, dictated by the Prophet (now section 132), contains no mention of the words “spiritual” or “wifery.” Interestingly, Bennett did not adopt other terms like “everlasting wifery,” “celestial wifery,” “eternal wifery,” or “spiritual marriage,” which is evidence that Joseph’s teachings and Bennett’s claims were completely unrelated to each other and casts significant doubt that Joseph Smith would have ever used the term as Bennett alleged.

An additional problem with Sarah’s alleged account, as filtered through John C. Bennett, is that the evidence strongly supports that they were sexually involved with each other. In August of 1842, non-Mormon72 J. B. Backenstos, signed an affidavit charging, “Doctor John C. Bennett, with having an illicit intercourse with Mrs. Orson Pratt, and some others, when said Bennett replied that she made a first rate go, and from personal observations I should have taken said Doctor Bennett and Mrs. Pratt as man and wife, had I not known to the contrary.”73 Ebenezer Robinson similarly reported in 1890: “In the spring of 1841 Dr. Bennett had a small neat house built for Elder Orson Pratt’s family [Sarah and one male child] and commenced boarding with them. Elder Pratt was absent on [Page 213]a mission to England.”74 John D. Lee recalled: “He [John C. Bennett] became intimate with Orson Pratt’s wife, while Pratt was on a mission. That he built her a fine frame house, and lodged with her, and used her as his wife.”75 Another Nauvooan recalled that Joseph Smith tried to intervene. Mary Ettie V. Coray Smith76 related:

Orson Pratt, then, as now [1858], one of the “Twelve,’ was sent by Joseph Smith on a mission to England. During his absence, his first (i.e. his lawful) wife, Sarah, occupied a house owned by John C. Bennett, a man of some note, and at that time, quartermaster-general of the Nauvoo Legion. Sarah was an educated woman, of fine accomplishments, and attracted the attention of the Prophet Joseph, who called upon her one day, and alleged he found John C. Bennett in bed with her. As we lived but across the street from her house we heard [Page 214]the whole uproar. Sarah ordered the Prophet out of the house, and the Prophet used obscene language to her.77

Precisely what Joseph and Sarah discussed is not known; however, she later complained that Joseph made an offensive “proposal” to her.78 In a meeting of the Twelve Apostles dated 20 January 1843, Joseph Smith told Orson that Sarah “lied about me,” saying, “I never made the offer which she said I did.”79 In 1845, Orson Pratt was interviewed by Sidney Rigdon. After the interview, Rigdon concluded that Orson was “literally telling the people that all Smith said about his wife was true.” Rigdon added: “He has left on the character of his wife a stain, by this degraded condescension, that he can never wash out. … Pratt is determined to make us believe it, by virtually declaring it was true; for if he was wrong when he called Smith a liar, then his wife was guilty of the charges preferred.”80

If he was going to opine on these matters, Grant Palmer should have been aware of this data. And, had he known, he ought then have refrained from including such feeble evidence to support allegations of impropriety between Joseph Smith and Sarah Pratt without making a cogent case, which overcomes the limitations we outline above.

#9: Melissa Schindle

Palmer continues to quote John C. Bennett’s publication, History of the Saints, by reproducing an affidavit from Melissa Schindle (p. 14):

[Page 215]In the fall of 1841, she was staying one night with the widow Fuller, who has recently been married to a Mr. Warren, in the city of Nauvoo, and that Joseph Smith came into the room where she was sleeping about 10 o’clock at night, and after making a few remarks came to her bedside, and asked her if he could have the privilege of sleeping with her. She immediately replied no. He, on the receipt of the above answer told her it was the will of the Lord that he should have illicit intercourse with her, and that he never proceeded to do any thing of that kind with any woman without first having the will of the Lord on the subject; and further he told her that if she would consent to let him have such intercourse with her, she could make his house her home as long as she wished to do so, and that she should never want for anything it was in his power to assist her to — but she would not consent to it. He then told her that if she would let him sleep with her that night he would give her five dollars — but she refused all his propositions. He then told her that she must never tell of his propositions to her, for he had ALL influence in that place, and if she told he would ruin her character, and she would be under the necessity of leaving. He then went to an adjoining bed where the Widow [Fuller] was sleeping — got into bed with her and laid there until about 1 o’clock, when he got up, bid them good night, and left them, and further this deponent saith not. MELISSA (her X mark) SCHINDLE.

Subscribed and sworn to before me, this 2d day July, 1842. A. FULKERSON, J. P. (seal).81

[Page 216]Palmer evidently takes this affidavit at face value, writing that on an “1841 evening … Melissa Schindle was propositioned by Smith,” and “Melissa rejected” Joseph Smith’s offer (p. 14). However, the affidavit’s credibility is questionable on several grounds.

Schindle’s illiteracy, indicated by her signing an “X,” shows that she would have required assistance from other individuals — including, potentially, John C. Bennett — to compose the document. Two weeks after the affidavit was published, Melissa Schindle’s moral character was questioned in Nauvoo’s secular newspaper, The Wasp: “Who is Mrs. Shindle? A harlot.”82 Catherine Fuller (see case #10) was tried before the Nauvoo High Council on 25 May 1842 for immoral activity with John C. Bennett. During her trial, she accused Bennett of also sleeping with Melissa Schindle. 83 D. Michael Quinn lists her as one of Bennett’s “free-love” companions.84

The events described in the affidavit include several details that seem implausible. In 1841 Nauvoo, no man — even Joseph Smith — was likely to be allowed to wander into a room where women were already in bed sleeping at ten o’clock at night.

Schindle’s claim that Joseph Smith “told her it was the will of the Lord that he should have illicit intercourse with her” depicts him as an adulterous hypocrite, acknowledging from the onset that the relationship would have been “illicit.” Such a depiction of the Prophet contradicts the numerous other public and private evidences that Joseph taught and practiced a different moral standard.

It is also implausible that the Prophet would offer Schindle to “make his house her home” if she would acquiesce. It seems clear that Emma, the Prophet’s legal wife, would not have tolerated such an arrangement at their Nauvoo homestead. [Page 217](The Smiths did not move into the spacious Nauvoo Mansion until August of 1843.)

The offering of money, “five dollars,” is also singular. None of Joseph’s plural wives reported any promises of material benefits or financial favors to them. Plural wife Lucy Walker recalled Joseph telling her as he discussed a plural sealing with her: “I have no flattering words to offer.”85 There is simply too much here that does not add up.

#10: Catherine Warren Fuller

In her affidavit, Schindle declared that she refused Joseph Smith’s advances and then witnessed sexual relations between him and Catherine Fuller. To support this allegation, Palmer also quotes an affidavit from John C. Bennett (p. 14):

…he [John C. Bennett] has seen Joseph Smith in bed with Mrs. ______, Mrs. ______, and that he has seen him in the act of cohabitation with Mrs. ______, and Mrs. ______, all four of whom he seduced by telling him that the Lord had granted the blessing of Jacob, and that there was no sin in it — that he told him that Bates Noble married him to ____ ______, and that Brigham Young married him to ____ ______, that he had free access to Mrs. ______, Mrs. ______, and Mrs. ______, and various others.86

Bennett asserted that Joseph Smith was sleeping with seven married women, and Bennett personally witnessed relations between the Prophet and four of them. Bennett’s affidavit is remarkable for its voyeuristic features. Were Joseph behaving as described, it would be surprising if he allowed any man or woman the level of access Bennett claimed. It is also dubious to claim that the women would have permitted it. Bennett and Palmer’s reconstruction makes them passive objects or props, not realistic human beings of their time and place.

[Page 218]

Despite his many claims of being a polygamy confidant of Joseph Smith’s, an examination of Bennett’s writings [Page 219]demonstrates that he learned nothing about eternal marriage from the Prophet.

In a 28 October 1843 letter written to the Iowa Hawk Eye newspaper, Bennett reported that “This ‘marrying for eternity’ is not the ‘Spiritual Wife doctrine’ noticed in my Expose [The History of the Saints], but is an entirely new doctrine established by special Revelation.” That is, eternal marriage was “an entirely new doctrine” to Bennett. Since Joseph never taught plural marriage in Nauvoo without emphasizing its eternal nature, Bennett’s admission that he had never heard of eternal marriage in Nauvoo is a tacit admission that he never learned of plural marriage there either.

As discussed above, on 25 May 1842, Catherine was called before the Nauvoo High Council on charges of “unchaste and unvirtuous” behavior — not with Joseph Smith, but with John C. Bennett and other men:

The defendant confessed to the charge and gave the names of several others who had been guilty of having unlawful intercourse with her stating that they taught the doctrine that it was right to have free intercourse with women and that the heads of the Church also taught and practiced it which things caused her to be led away thinking it to be right but becoming convinced that it was not right and learning that the heads of the church did not believe nor practice such things she was willing to confess her sins and did repent before God for what she had done and desired earnestly that the Council would forgive her and covenanted that she would hence forth do so no more.87

In this confession Catherine directly contradicts Bennett’s accusation, acknowledging that the “heads of the church,” which would have included Joseph Smith, “did not believe [Page 220]nor practice” what Bennett described as “free intercourse.” Given that Catherine exposed Bennett and implicated Melissa Schindle in fornication with Bennett, it is perhaps not surprising that Bennett would try to discredit her, though his zeal resulted in less-than-plausible slander.

“At Least Some Plausibility”

As quoted above, Grant Palmer explained in his introduction: “a number of sexual allegations are leveled against Smith, several of which I think contain so little information they are not worth mentioning.” Instead, he chose these ten “declarations” because he believed they “have at least some plausibility of being true.” Questions of “plausibility” can be answered in different ways by observers, usually due to the individual biases they possess. Apparently, these ten allegations are the most convincing evidences Palmer could identify in the entire historical record in order to support his belief that Joseph Smith “was accused of illicit sexual conduct with a number of women from 1827 on, until his death in 1844” (p. 3). If so, then the “allegations” that were “not worth mentioning” because they were more skimpily documented must have been very dubious indeed.

Part 2 — Other Historical Claims and Errors

No Accuser Equals No Sin?

On page 16, Palmer proposes an utterly unlikely interpretation of Joseph Smith’s public teaching on 7 November 1841: “If you do not accuse each other, God will not accuse you.”88 There is no question that Bennett utilized this seduction line. Margaret Nyman testified that Chauncey Higbee, a follower of Bennett, approached her saying: “Any respectable female might indulge in sexual intercourse, and there was no [Page 221]sin in it, provided the person so indulging keep the same to herself; for there could be no sin where there was no accuser.”89

Palmer extrapolates and claims that by 7 November 1841, “this philosophy was already being practiced by Joseph Smith and John C. Bennett” (p. 16). Unfortunately for Palmer, he provides no evidence to support the tenuous claim that the Prophet did so. It seems that if John C. Bennett had known about eternal marriage and celestial sealing, he would have exploited those secret teachings rather than twisting a public statement from the Prophet. Palmer includes Joseph in his net without any documentation.

With the exception of Bennett, there are likewise no witnesses that Joseph would ever have tolerated secret sexual liaisons between unmarried individuals. On the contrary, he disciplined such behavior when it came to his attention.

Evidence or Unscholarly Propaganda?

Halfway through the article, Palmer summarizes:

Improper sexual advances relating to the Stowell daughters, Eliza Winters, Marinda Nancy Johnson, Vienna Jacques, Miss Hill, Fanny Alger, Lucinda Harris, Sarah Pratt, Melissa Schindle, and Catherine Fuller Warren were made against the character of Joseph Smith from 1827–1841. (p. 16)

Palmer apparently believes his interpretations regarding these alleged interactions, but our closer look reveals that none of them constitute a credible report of sexual immorality.

Expanding his case with innuendo, Palmer writes:

Additionally, of the thirty-three women listed by Todd Compton as being plural wives of Joseph Smith, twelve do not have an officiator, ceremony or witness to their marriage/sealing. Fanny Alger and Mrs. Lucinda [Page 222]Harris, who we have already discussed, fall into this category in the 1830s; Mrs. Sylvia Sessions, Mrs. Elizabeth Durfee, Mrs. Sarah Cleveland, and widow Delcena Johnson, in 1842; and single women, Flora Ann Woodworth, Sarah and Maria Lawrence, Hannah Ells, Olive Frost and Nancy Winchester, in 1843. Is inadequate record keeping the problem, or are some of these women — especially the married ones — sexual consent relationships? (p. 16)

It appears Palmer simply performed a superficial review of these women and then drew his extreme conclusion. If he had dug a little further he would have learned that documentation exists showing that Levi Hancock performed the marriage of Fanny Alger; Andrew Jenson documented a sealing between the Prophet and Sylvia Sessions; Emma Smith participated in the sealings of Sarah and Maria Lawrence; and valid eternal marriage ceremonies were attested for Olive Frost (by Mary Ann Frost), Elizabeth Davis [Durfee] (by Eliza R. Snow), Sarah Cleveland (by John L. Smith), Hannah Ells (by William Clayton), Nancy Winchester (by Eliza R. Snow), Delcena Johnson (by Benjamin F. Johnson), and Flora Ann Woodworth (by Helen Mar Whitney). The volume of evidence Palmer needed to ignore to arrive at his conclusion is impressive.90

Joseph Smith’s “Tremendous Power Over Church Members”?

Palmer’s version of Joseph Smith’s polygamy becomes more entertaining as he asserts:

Claiming heavenly sealing keys to “bind and loose” gave Smith tremendous power over church members. He used it as an inducement to persuade at least three and probably four young females to accept his proposals between mid-July 1842 and mid-May 1843. Sarah Ann Whitney, Helen Mar Kimball, Lucy Walker and perhaps Flora Woodworth — all between the ages [Page 223]of fourteen and seventeen[ — ]were persuaded by this approach. (pp. 17–18.)

Specifically, Palmer asserts: “Newel K. Whitney, Sarah Ann’s father was promised by Smith to receive ‘eternal life to all your house, both old and young,’ by having Sarah Ann marry him” (p. 18). In fact, Palmer misrepresents the statement:

Verily thus saith the Lord unto my servant N. K. Whitney the thing that my servant Joseph Smith has made known unto you and your family and which you have agreed upon is right in mine eyes and shall be crowned upon your heads with honor and immortality and eternal life to all your house both old and young because of the lineage of my priesthood saith the Lord it shall be upon you and upon your children after you from generation to generation By virtue of the Holy promise which I now make unto you saith the Lord.91

Palmer affirms that the “thing” capable of bringing “honor and immortality and eternal life to all your house both old and young … and upon your children after you from generation to generation” is Joseph’s plural marriage to Sarah, which is an incomplete interpretation. He ignores the other factor at play in Joseph’s communications with the Whitney’s: the eternal marriage sealing of Newel and Elizabeth Whitney on 21 August 1842. Three days prior to their sealing, Joseph wrote them urgently of “one thing I want to see you for it is to git the fulness of my blessings sealed upon our heads.” Joseph praised the Whitneys “for I know the goodness of your hearts, and [Page 224]that you will do the will of the Lord, when it is made known to you.”92

Plural marriage is thus a token of the Whitneys’ willingness to obey God, but their complete commitment and the eternal sealing that it permits seems to us the more likely source of the promised blessings.

Helen Mar Kimball’s father arranged for her to be sealed to Joseph Smith. Palmer writes: “He [Joseph Smith] told Helen Mar Kimball in front of her father, Heber C. Kimball, that: ‘If you will take this step, it will ensure your eternal salvation & exaltation and that of your father’s household & all of your kindred’” (p. 18).93 Palmer forgets to include Helen’s other comment regarding the teachings she heard that day: “I confess that I was too young or too ’foolish’ to comprehend and appreciate all” that Joseph Smith taught.94 Contemporaneous evidence from more mature family members who were better positioned to “comprehend and appreciate” the Prophet’s promises to Helen demonstrates that she did, in fact, misunderstand the blessings predicated on this sealing.95

Palmer misrepresents still another relationship: “Lucy Walker, like the other two girls was told by Smith that by marrying him, ‘that it would prove an everlasting blessing to my father’s house’” (p. 18). A closer look at the entire quote shows that it is the principle of sealing, not Lucy’s specific marriage to Joseph that would bring blessings: “He [Joseph Smith] fully explained to me the principle of plural or celestial marriage. He said this principle was again to be restored for the benefit of the human family, that it would prove an everlasting blessing to [Page 225]my father’s house, and form a chain that could never be broken, worlds without end.”96

Sending Men on Missions?

By quoting secondary sources such as Todd Compton, Palmer asserts:

A second method Smith used to get females to say yes to his proposals was to send family males on a mission that might or did object to his advances. … Smith directly approached young Lucy Walker only after sending her father, John Walker, on a mission. He also sent Horace Whitney on a mission because he felt that Horace was too close to his sister Sarah Ann, and would oppose the marriage.97 Smith married Marinda Nancy Johnson Hyde, a year before her husband Orson, an Apostle, returned from his mission. (p. 19)

A closer look reveals that John Walker was sent on a mission to help his health. Lucy recalled: “The Prophet came to our rescue. He said: ‘If you remain here, Brother Walker, you will soon follow your wife. You must have a change of scene, a change of climate.’ … [M]y father sought to comfort us by saying two years would soon pass away, then with renewed health” 98 and upon his return he was told and approved of the marriage. Similarly, Horace Whitney approved of Sarah’s sealing upon learning of it after his mission was finished.

Two separate sealing dates for Joseph Smith’s marriage to Marinda Nancy Johnson are available. Joseph Smith’s journal contains a list of plural marriages in the handwriting of Thomas Bullock is found written after the 14 July 1843 entry: “Apri 42 marinda Johnson to Joseph Smith,” well over a year [Page 226]after Orson had left on his mission to Palestine.99 However, the second sealing date of “May 1843” was written on an affidavit she personally signed. The significance of the two dates is unknown, but as evidence that the Prophet would send a woman’s family members on missions in order to marry her, these cases are not impressive. If Orson had been sent away so Joseph could marry his wife, why did Joseph wait at least a year before proceeding? And, why does Palmer emphasize the amount of time remaining on Orson’s mission, instead of the amount of time that had elapsed before the marriage? His choice shades the account to Joseph’s disadvantage.

Angel with a Sword

Palmer writes that Joseph Smith told Zina Huntington: “The angel will slay me with a sword if you don’t accept my proposal” (p. 19). This entertaining fabrication is not supported by any known account of Joseph Smith’s visit with the angel.100 In fact, Zina testified that Joseph never spoke to her until the sealing. Zina explained: “My brother Dimick told me what Joseph had told him” regarding plural marriage, and she reported: “Joseph did not come until afterwards. … I received it from Joseph through my brother Dimick.”101 Importantly, Mary Elizabeth Rollins stated that the angel did not appear with a sword until “early February” of 1842 — this was months after Joseph’s sealing to Zina, so a claim about a sword to Zina appears anachronistic.102

[Page 227]Throughout Palmer’s discussion, he seems unaware of Joseph’s open condemnation of a “plurality of husbands.” That is, at no time could a woman have two husbands according to God’s laws.103 In the cases of Zina Huntington (legal wife of Henry Jacobs) and Mary Elizabeth Rollins (legal wife of Adam Lightner), the women chose Joseph over their civils spouses in “eternity only” sealings that begin after death.104

Joseph H. Jackson?

Just when we thought Palmer’s documentation could not get any worse, he quotes Joseph H. Jackson:

For example, he [Joseph Smith] asked Joseph Jackson for help in winning over Jane Law in January of 1844, stating that Smith: “Informed me he had been endeavoring for some two months, to get Mrs. William Law for a spiritual wife. He said that he had used every argument in his power to convince her of the correctness of his doctrine, but could not succeed.”105 (pp. 20–21)

Joseph H. Jackson published an extraordinary account of his alleged interactions with Joseph Smith, including those with William and Jane Law in 1844.106 However, the historical record demonstrates that Jackson had few opportunities for [Page 228]private conversations with the Prophet. Jackson lied when he introduced himself as a “Catholic priest,” on 18 May 1843.107 Two days later, William Clayton recorded Joseph remarking, “Jackson appears a fine and noble fellow but is reduced in circumstances.” Apparently Jackson immediately disappointed the Prophet’s expectations. Only three days later, Joseph told Clayton, “Jackson is rotten hearted.” This gives the supposed Catholic priest no more than a five-day window without Joseph’s distrust.108

It appears that Joseph Jackson sought to marry Lovina Smith, daughter of Hyrum Smith, but was rebuffed by both Hyrum and Joseph. One month before his death the Prophet exclaimed: “Jackson has committed murder, robbery, and perjury; and I can prove it by half-a-dozen witnesses.”109 Given how closely Joseph guarded the secret of plural marriage in Nauvoo, it is extraordinary to claim that he would unveil everything less than a week after first meeting Jackson.

Slandering Women Who Refused Plural Proposals?

Palmer seems to believe John C. Bennett’s claim that if a woman refused a plural proposal, Joseph Smith would ruin her reputation (p. 22).110 History records that Joseph was turned down by seven women. His preferred response was to quietly let the matter rest. No evidence of retaliatory excommunications or other vengeful reactions have been found, although twice he sought to counteract allegations he considered untrue.

[Page 229]Benjamin F. Johnson wrote of one rejection, relating that the Prophet “asked me for my youngest sister, Esther M. I told him she was promised in marriage to my wife’s brother. He said, ‘Well, let them marry, for it will all come right.’”111 Esther and her future husband were married by Almon Babbit in Nauvoo on 4 April 1844.112

In another case, on 15 September 1843, William Clayton recorded an incident regarding Lydia Moon: “He [Joseph Smith] finally asked if I would not give Lydia Moon to him I said I would so far as I had any thing to do in it. He requested me to talk to her.”113 Two days later, Clayton wrote: “I had some talk with Lydia. She seems to receive it kindly but says she has promised her mother not to marry while her mother lives and she thinks she won’t.”114 Lydia was not sealed to Joseph.

Another unsuccessful proposal occurred with Sarah Granger Kimball, who was legally married to non-Mormon Hiram Kimball:

Early in 1842, Joseph Smith taught me the principle of marriage for eternity, and the doctrine of plural marriage. He said that in teaching this he realized that he jeopardized his life; but God had revealed it to him many years before as a privilege with blessings, now God had revealed it again and instructed him to teach with commandment, as the Church could travel (progress) no further without the introduction of this principle. I asked him to teach it to some one else. He looked at me reprovingly and said, “Will you tell me who to teach it to? God required me to teach it to you, and leave you with the responsibility of believing or disbelieving.” He said, “I will not cease to pray for you, [Page 230]and if you will seek unto God in prayer, you will not be led into temptation.”115

After this snub, Sarah Kimball sent Joseph on his way. His only response was to encourage her and to pray for her.

Cordelia C. Morley recounted a similar situation: “In the spring of forty-four, plural marriage was introduced to me by my parents from Joseph Smith, asking their consent and a request to me to be his wife. Imagine if you can my feelings, to be a plural wife, something I never thought I ever could. I knew nothing of such religion and could not accept it. Neither did I.”116 However, Cordelia had second thoughts and was sealed to the Prophet after his death. 117

Rachel Ivins also turned Joseph down, but she was later sealed to him by proxy in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City on 29 November 1855.118

All five of these rejections came and went, unknown to most in Nauvoo. According to available records, these women suffered no consequences at Joseph Smith’s hand, directly or indirectly, for spurning him. Had the woman not personally recounted the events afterwards, knowledge of the proposals would have likely been lost to later generations.

However, Joseph’s interactions with two women, Sarah Pratt and Nancy Rigdon, demonstrate that he would defend himself against claims he considered to be false.119 Joseph likely proposed plural marriage to Nancy, but she declined.120 While [Page 231]she did not publicly accuse the Prophet, she also did not keep the episode secret. One account claimed that “she like a fool had to go & blab it.”121 Months later John C. Bennett broadcast his version of the episode in a letter to the Sangamo Journal.122 Joseph publicly denied Bennett’s account, and within weeks Nancy denounced Bennett’s claims in a statement made through her father, Sidney Rigdon.123

Joseph likewise publicly refuted Sarah Pratt’s accusations (see discussion above, Part 1, Claim #8). He later confided to Orson Pratt, Sarah’s husband that Sarah “lied about me.”124 Orson would eventually conclude that Joseph had told the truth.125

When we review Joseph Smith’s actions in the cases of Nancy Rigdon and Sarah Pratt and compare them to his reactions upon being rebuffed by Esther M. Johnson, Lydia Moon, Sarah Granger Kimball, Cordelia C. Morley, and Rachel Ivins, the historical data make it clear that if Nancy and Sarah had kept silent concerning Joseph Smith’s discussion of plurality, the public scandals that followed would have almost certainly been avoided.

Helen Mar Kimball — Consummated Plural Marriage?

Without any supporting evidence, Palmer asserts:

Helen [Mar Kimball] thought she had married Smith “for eternity alone” but soon found out differently. She said Joseph protected her from the attention of young men, and that her marriage was “more than ceremony,” [Page 232]suggesting that she did have or would have a sexual relationship with Smith. (p. 13)

In fact there is no evidence that the sealing between Joseph and Helen was intended or said to be “for eternity only.” However, several observations argue that Joseph’s sealing to Helen Mar Kimball was never consummated. Heber C. Kimball requested that Joseph be sealed to his daughter, to which Helen agreed.126 There is no historical data suggesting that the Prophet initiated or actively sought this plural union.

In 1892, depositions seeking to discover if Joseph Smith practiced sexual polygamy were sought for litigation between the RLDS Church and the Church of Christ (Temple Lot). Helen Mar Kimball was not called to testify, even though she lived nearby and had written two books defending plural marriage. Instead, three wives who lived further away were summoned, and all affirmed sexual relations with the Prophet in their plural marriages. The most likely reason for Helen’s absence was her inability to offer the required testimony of a sealing with a sexual dimension.

While we have no firsthand accounts of the Prophet’s counsel on marriages to women in their teens, a pattern which began in Nauvoo and was carried over into Utah is instructive. This protocol taught that polygamous husbands should allow young wives to physically mature before beginning a family with them. Eugene E. Campbell described Brigham’s latter instructions:

To one man at Fort Supply, Young explained, “I don’t object to your taking sisters named in your letter to wife if they are not too young and their parents and your president and all connected are satisfied, but I do not want children to be married to men before an age which their mothers can generally best determine.” Writing to another man in Spanish Fork, he said, “Go [Page 233]ahead and marry them, but leave the children to grow.” … To Louis Robinson, head of the church at Fort Bridger, Young advised, “Take good women, but let the children grow, then they will be able to bear children after a few years without injury.”127

“Multiply and Replenish the Earth”

Palmer seems obsessed with the fact that some of Joseph Smith’s plural marriages included sexual relations (pp. 22–28). In fact, to “multiply and replenish the earth” was a lesser reason for the establishment of plural marriage. God explained to the Nephites that He might “command” plural marriage in order to “raise up seed” to Him (Jacob 2:30). Hales has made all known documentation of sexuality in twelve of the plural marriages available in print and online.128

At present, there is evidence of two or three children fathered by Joseph Smith via plurality. Even if that number were doubled, it would still represent a surprisingly small number of children if sexual relations occurred often. The Prophet was virile, having fathered eight children with Emma despite long periods of time apart and challenging schedules.

A review of the child-bearing chronology of Joseph Smith’s wives after his death and their remarriages demonstrates impressive fertility in several of the women. Most of them married within two years after the martyrdom and prior to the Saints leaving for the West. Three of the women became pregnant within weeks after remarrying. Sarah Ann Whitney, who was sealed to Joseph Smith for twenty-three months, married Heber C. Kimball on 17 March 1845, and, based on the birth date of their first child, became pregnant approximately June 15.129 She bore Heber Kimball seven children between [Page 234]1846 and 1858. Lucy Walker, who was sealed to the Prophet for fourteen months, also married Kimball. About three months after their 8 February 1845 marriage, she became pregnant.130 She gave birth to nine of Kimball’s children between 1846 and 1864. Malissa Lott, who was sealed to Joseph Smith in September 1843, married Ira Jones Willes on 13 May 1849. Their first child was born 22 April 1850, with conception occurring approximately 30 July 1849 (or eleven weeks after the wedding ceremony). Seven Willes children were born between 1850 and 1863. Emily Partridge bore Brigham Young seven offspring between 1845 and 1862. Her sister Eliza married Amasa Lyman, and together they had five children between 1844 and 1860. Several other plural wives, including Louisa Beaman, Martha McBride, and Nancy Winchester, also remarried and became pregnant. In light of the obvious fertility of many of Joseph Smith’s plural wives (and Joseph himself with Emma), it seems that they either bore him children who are unknown today or that sexual relations in the marriages did not occur often.

Conclusion: Unsubstantiated Opinion and Poor Documentation

Grant Palmer is certainly entitled to his opinion of Joseph Smith and plural marriage. However, it is important for observers to discern whether his opinion is based upon documented history or simply his own notions. Palmer is not entitled to pass off his opinions — most poorly grounded, and some utterly fanciful — as historical fact.

Throughout his paper, Palmer consistently succumbs to a weakness found in similar antagonistic writings — he portrays Joseph Smith as a blatant hypocrite and depicts Church members as such gullible dupes that they remain blissfully unaware of what Joseph was up to. In doing so, Palmer enters the realm of historical fiction. To assume that Joseph Smith could have blithely transgressed his own theological teachings without disillusioning followers like Brigham Young, John [Page 235]Taylor, Eliza R. Snow, Zina Huntington, and many others is unrealistic. Joseph spent a good part of his life under intense scrutiny. Most of his closest followers were too perceptive to be bamboozled and too religious to become accomplices in a deliberate deception.131 Even Fawn Brodie admitted, “The best evidence of the magnetism of the Mormon religion was that it could attract men with the quality of Brigham Young, whose tremendous energy and shrewd intelligence were not easily directed by any influence outside himself.”132

Our review of Palmer’s methodology reveals a reconstruction filled with implausibilities and abysmally poor evidentiary support, which undermines the accuracy of most of his conclusions. There seems to be little doubt that Grant Palmer believes his version of Joseph Smith’s polygamy, but there seems to be equally little reason that anyone else should.[Page 236]

1. Grant H. Palmer, “Sexual Allegations against Joseph Smith, 1829–1835,” typescript, n.d. [after 1999], UU_Accn0900, H. Michael Marquardt Collection, Marriott Library. Photocopy in possession of Brian C. Hales.

2. Numerous non-LDS media outlets have noted the bias of the “anti-Mormon website called MormonThink.” John Johnson, “UK Judge to Mormon Leader: Defend Your Religion in Court,” Newser, 5 February 2014, http://www.newser.com/story/181832/uk-judge-to-mormon-leader-defend-your-religion-in-court.html. For further examples, see “How Does the News Media View MormonThink.com?” FairMormon Answers Wiki, accessed 23 September 2014, http://en.fairmormon.org/Criticism_of_Mormonism/Websites/MormonThink/Media_coverage_of_MormonThink.

3. Van Wagoner likewise cites this source as “Benjamin F. Winchester.” Richard S. Van Wagoner, Mormon Polygamy: A History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 4.

4. Brigham Young, cited in Scott G. Kenny, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 9 vols. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985), 7:31 (24 September 1871).

5. Comparable tactics are used in the similarly flawed and equally ideologically driven account found in George D. Smith, Nauvoo Polygamy: “… but we called it celestial marriage” (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2008), 15–20.

6. “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 3/11 (1 April 1842): 749.

7. “History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” The Joseph Smith Papers, Addenda, Note C • 1820–1823, accessed 24 September 2014, http://josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834?p=5#!/paperSummary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834&p=139.

8. Joseph Smith to Oliver Cowdery, Messenger and Advocate 1/3 (December 1834): 40, emphasis added.

9. See, for example, Orson Hyde, 1832 mission journal for date, typescript, American Collection, Box 8670, M 82, Vol. 11, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University or “From the Boston Patriot,” National Intelligencer, 13 November 1819.

10. “History of Joseph Smith — continued,” Times and Seasons 4/3 (15 December 1842): 41.