Abstract: In previous and pending publications I have proposed interpretations of various features of Nephi’s writings. In this paper I undertake a comprehensive discussion of the seven passages in which Nephi and his successor Jacob explain the difference between the large and the small plates and describe the divinely mandated profile for each. While most readers of the Book of Mormon have been satisfied with the simple distinction between the large plates in which the large plates are a comprehensive historical record of the Nephite experience and the small plates are a record of selected spiritual experiences, including revelations and prophecies, that approach has been challenged in some academic writing. What has been missing in this literature is a comprehensive and focused analysis of all seven of the textual profiles for these two Nephite records. In the following analysis, I invoke the insights of Hebrew rhetoric as developed by Hebrew Bible scholars over the past half century to articulate a vision of how these scattered explanations are designed and placed to support the larger rhetorical structures Nephi has built into his two books. The conclusions reached support the traditional approach to these texts.

The intent of this paper is not to advance either a comprehensive or a final interpretation of Nephi’s writings in First and Second Nephi. Rather, it is limited to a discussion of one dimension of those writings which has not previously been adequately identified and analyzed, but which should play an important role for any attempt at comprehensive interpretation. My own understanding of Nephi’s two books continues to evolve in important ways and benefits continually from the insights of other students of the text. I agree with Ben McGuire’s conclusion [Page 100]that both individuals and reading communities should keep their interpretations of this sacred text open to future insights.1

Readers of the Book of Mormon commonly assume the adequacy of a simple and straightforward explanation for the existence of Nephi’s Small Plates (sometimes abbreviated herein as SP).2 As explained at various points in the text, Nephi had undertaken a shorter version of his Large Plates (LP) record by selecting out the spiritual teachings, prophecies and revelations for a more focused presentation. But the adequacy of that explanation has come under considerable strain from two very different directions. In 1986 Fred Axelgard advanced the idea that the description provided for the Large Plates of Nephi as being more historical also applied to all of First Nephi and the first five chapters of Second Nephi.3 And now in an as yet unpublished working paper, I am advancing a new paradigm for interpretation of the Small Plates that both supports and pushes well beyond the traditional analysis by emphasizing Nephi’s use of Hebrew rhetoric4 to structure all of First [Page 101]and Second Nephi as a carefully calculated expansion and elaboration of Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life.5 In this essay I will explain why Nephi provides so many versions of his explanations for the Small Plates by showing how these repeated passages provide key pieces of Nephi’s rhetorical structures.6 Finally, the information will be condensed into a table that displays the multiple ways in which the seven different profiles for Nephi’s two sets of plates are composed and related.

The Small Plates of Nephi and Hebrew Rhetoric

Nephi’s writings constitute the bulk of the Small Plates of Nephi as we refer to them today. When he undertook that new composition thirty years after leaving Jerusalem, he was a mature prophet/ruler. He drew upon three primary records and his own experience:

- The Brass Plates that Lehi’s family brought from Jerusalem contained the five books of Moses, the genealogy of ancient Joseph’s descendants, “a record of the Jews from the beginning, even down to the commencement of the reign of Zedekiah, king of Judah, and also the prophecies of the holy prophets from the beginning, … and also many prophecies which have been spoken by the mouth of Jeremiah” (1 Nephi 5:12–13).7 These plates included the writings of prophets not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible8 and apparently a version of Genesis similar to the Book of Moses that was revealed [Page 102]to Joseph Smith.9 The genealogy it contained and possibly the selection of prophetic texts it preserved belonged to the descendants of Joseph of Egypt, or at least to the descendants of his son Manasseh. The bulk of, or at least the older materials in, the Brass Plates were written in Egyptian and appear to have been a Manassite record preserved in the northern kingdom by a Josephite scribal school.10

- The record of his father Lehi minimally contained original accounts of his numerous revelations and probably his own account of his life and experiences.11

- And the Large Plates of Nephi contained Nephi’s own record of the revelations received by Lehi, Nephi, and Jacob, their teachings, and the history of their descendants that Nephi had been commanded to record at some earlier point.12 This was the main record handed through generations of Nephite kings and prophets and which eventually provided Mormon a primary resource for the abridgment which he prepared at the end of the Nephite dispensation and which Joseph Smith translated “by the gift and power of God” and published as the Book of Mormon in 1830.

[Page 103]New Plates, New Profile

Nephi provides us with no less than six explanations of the differences between, and reasons for, his two sets of plates.13 His brother Jacob begins his continuation of Nephi’s Small Plates with a seventh and long explanation of those differences according to instructions he had received from Nephi (Jacob 1:1–8). From these seven explanations, we learn that both writing projects were responses to direct commandments of the Lord. Nephi was surprised by the second command that came later in his life but took full advantage of his earlier work and his prior scribal education to produce a thoroughly planned and concise expression of the central revelations and teachings given to Lehi and Nephi for their dispensation. The importance of these explanations for Nephi is emphasized not only by their number, but also by their rhetorical structuring and placement.

All six of Nephi’s explanations are themselves structured in classical Hebrew rhetorical forms and include six chiasms, two sets of parallel couplets, and two sets of parallel triplets. All but one are placed strategically in the text to support larger rhetorical structures — as will be explained further below. In Hebrew rhetoric, these rhetorical forms serve to demarcate and identify these passages as separate and important textual units serving specific purposes — which purposes can be inferred from their contents and contexts in each case.

Two additional passages provide passing comments that also confirm the traditional understanding of the distinction Nephi made between his large and small plates — without rising to the level of independent Hebrew rhetorical structures. In describing the tense family division he was dealing with immediately after the death of Father Lehi, Nephi writes in these Small Plates that the extended sayings of Lehi “are written upon mine other plates, for a more history part are written upon mine other plates. And upon these plates I write the things of my soul and many of the scriptures which are engraven upon the plates of brass” (2 Nephi 4:14‒15). And at the very end of his writings in the Small Plates, Nephi shifts into a reflective farewell mode that does not clearly distinguish the two sets of plates and could be interpreted to refer to both. Pondering the potential future impact of his writings, he recognizes that many will “harden their hearts against the Holy Spirit” and “cast many things away which are written and esteem them as things of naught” (2 Nephi 33:2). [Page 104]Nephi has struggled endlessly with that problem in his own family, as his writings forcefully attest. Now at the end, he simply invokes the Semitic idiom of idem per idem to close the debate: “I Nephi have written what I have written” (2 Nephi 33:3).14

2 Nephi 5:28–34

The sixth and final explanation offered by Nephi provides the specific historical context for the original commandment to make this second record and tells us it was not yet finished after a full decade of work. While the full text and its intricate rhetorical structure must have been worked out by this point, he had only reached 2 Nephi 5 in the process of engraving his composition onto the metal plates. Like most others that have written about the Small Plates, I used to assume that the form and content evolved over the decade or more that Nephi spent writing First and Second Nephi. But as is obvious in my recent writings, I now see strong evidence that these two books were carefully designed and polished as a finished whole before being committed to their final form on metal plates.15

| A |

And thirty years had passed away from the time we left Jerusalem. |

| B |

And I Nephi had kept the records upon my plates (LP) which I had made of my people thus far. |

| C |

And it came to pass that the Lord God said unto me: |

|

a “Make other plates (SP); |

|

|

b and thou shalt engraven many things upon them (SP) which are good in my sight for the profit of thy people.” |

|

| D |

Wherefore I Nephi, to be obedient to the commandments of the Lord, went |

| C* |

And I engravened that which is pleasing unto God. |

|

a And if my people be pleased with the things of God, |

|

|

[Page 105]b they be pleased with mine engravings which are upon these plates (SP). |

|

| B* |

And if my people desire to know the more particular part of the history of my people, they must search mine other plates (LP). |

| A* |

And it sufficeth me to say that forty years had passed away, and we had already had wars and contentions with our brethren. |

While this last account helps us understand the historical context, it does not do much to clarify the prescribed profile for the new plates beyond saying that they should contain only those things “which are good in my sight for the profit of thy people.” And we are told that the Large Plates contain “the more particular part of the history of my people.” Nephi’s other five explanations all occur in First Nephi and provide a much more complete explanation of the profile. But before looking at each of these individually, it will be instructive to consult Jacob’s version of that profile as summarized in detail at the very opening of his contribution to the Small Plates.

Jacob’s Version

Interestingly, Jacob’s account of the instructions given to him by Nephi gives us a much more complete and far richer explanation of the distinctive profiles assigned by divine mandate to the two sets of plates. We cannot miss what Jacob is doing when his opening line exactly mimics Nephi’s opening in the foregoing passage by informing us that “fifty-five years had passed away from the time that Lehi left Jerusalem.” But what follows is a considerably expanded statement of the guidelines he has been given by Nephi for choosing what to include in the Small Plates. By describing how those guidelines relate to his responsibilities and activities as the spiritual leader of his people, he provides us with a more practical and in-depth understanding of the Small Plates and their contents.

Jacob 1:1–8

For behold, it came to pass that fifty and five years had passed away from the time that Lehi left Jerusalem;

| A |

wherefore Nephi gave me Jacob a commandment concerning these small plates (SP) upon which these things are engraven. |

| B |

[Page 106]And he gave me Jacob a commandment that I should write upon these plates (SP) a few of the things which I considered to be most precious, |

|

1 that I should not touch save it were lightly concerning the history of this people, which are called the people of Nephi. |

|

|

2 For he said that the history of his people should be engraven upon his other plates (LP). |

|

| C |

and that I should preserve these plates (SP) and hand them down unto my seed from generation to generation. |

|

1 And if there were preaching which was sacred, |

|

|

a or revelation which was great, |

|

|

b or prophesying, |

|

|

2 that I should engraven the heads of them upon these plates (SP) and touch upon them as much as it were possible, |

|

|

a for Christ’s sake |

|

|

b and for the sake of our people. |

|

| D |

For because of faith and great anxiety, it truly had been made manifest unto us concerning our people what things should happen unto them. |

| E |

And we also had many revelations |

| E* |

and the spirit of much prophecy; |

| D* |

wherefore we knew of Christ and his kingdom, which should come. |

| C* |

Wherefore we labored diligently among our people That we might persuade them to come unto Christ |

|

1 and partake of the goodness of God, that they might enter into his rest, |

|

|

2 lest by any means he should swear in his wrath they should not enter in, |

|

|

a as in the provocation in the days of temptation |

|

|

b while the children of Israel were in the wilderness. |

|

| B* |

Wherefore we would to God that we could persuade all men |

|

1 not to rebel against God, to provoke him to anger, |

|

|

2 but that all men would believe in Christ |

|

|

a and view his death |

|

|

[Page 107]b and suffer his cross |

|

|

c and bear the shame of the world. |

|

| A* |

Wherefore I Jacob take it upon me to fulfill the commandment of my brother Nephi. (Jacob 1:1–8) |

This long passage does not constitute a clear chiasm with repeated terminology in each of its parallel elements. But it does seem to feature a chiastic organization in that it begins and ends with references to the commandment Jacob had received from Nephi — making it minimally a rhetorical inclusio. And the two center lines feature simple synonymous descriptions of the key contents of the Small Plates. Further, it is easy to believe that Jacob saw parallels in the other elements marked out here as parts of a possible chiasm that may have been more obvious in the original language.

Given some of the interpretive confusion in the literature about the divinely prescribed purposes for Nephi’s second record, it is more than helpful to have the instructions he gave to his chosen successor author and custodian of the small plates as he (Jacob) interpreted those instructions. For Jacob the distinction between the Small Plates and the Large Plates was both simple and clear. Inasmuch as the Large Plates contained the history of the people of Nephi, he was instructed to touch only lightly on that history in the Small Plates. Rather Jacob was to include only “a few of those things which [he] considered to be most precious,” whether they be “preaching which was sacred, or revelation which was great, or prophesying.”

Jacob then goes on to make it clear that he was talking about preaching, revelation, and prophecies about Christ. Nephi took a more gradual approach, sprinkling references to Christ throughout his text. He eventually made his focus on Christ explicit and clear:

For we labor diligently to write, to persuade our children and also our brethren to believe in Christ and to be reconciled to God, for we know that it is by grace that we are saved after all that we can do. And notwithstanding we believe in Christ, we keep the law of Moses and look forward with steadfastness unto Christ until the law shall be fulfilled, for for this end was the law given. Wherefore the law hath become dead unto us, and we are made alive in Christ because of our faith, yet we keep the law because of the commandments. And we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ; and we write according to our prophecies that [Page 108]our children may know to what source they may look for a remission of their sins. (2 Nephi 25:23–26)

Rather than beginning with a statement of his focus on Christ, Nephi made that focus even more powerfully clear by building the chiastic center of Second Nephi on that witness of Christ.16

One reviewer asked if I should recognize comments by three of Jacob’s successors as additional explanations of the purpose of the Small Plates, inasmuch as they seemed to echo Jacob’s phraseology that linked prophesy and revelation in Jacob 1:4 and 6, all in the context of references to the prophesied future coming of Christ. While I agree that these passages in Jarom 1:2, Omni 1;11, 25, and Words of Mormon 1:6 do reflect an awareness of Jacob’s account, they are only echoes and do not seem to constitute additional developed explanations of the purpose of the Small Plates, nor do they add additional insight on that issue. But the question does point to what eventually became a hard linkage in Nephite discourse between revelation and the spirit of prophecy, which I have treated at some length as one prominent example of the many hendiadyses that characterize Nephite discourse.17

As predicted by Nephi, Jacob and others found the Small Plates to be a precious resource as the spiritual leaders of the people of Nephi. That practical role had led Jacob to see the spiritual choices of the Nephites in a binary way:

Wherefore we labored diligently among our people that we might persuade them to come unto Christ and partake of the goodness of God, that they might enter into his rest. …

Wherefore we would to God that we could persuade all men not to rebel against God, to provoke him to anger, but that all men would believe in Christ and view his death and suffer his cross and bear the shame of the world. (Jacob 1:7–8)

Nephi’s Other Five Explanations

From these explanations, we learn that the Large Plates contain the “full account of the history of my people,” including “an account of the reigns of the kings and the wars and contentions of my people” (1 Nephi 9:2, 4). This included “the record of my father and also our journeyings in the [Page 109]wilderness and the prophecies of my father,” “the genealogy or [Lehi’s] forefathers,” and also “many of mine own prophecies” (1 Nephi 19:1–2). In his final explanation, Nephi says, “if my people desire to know the more particular part of the history of my people, they must search mine other plates” — the Large Plates (2 Nephi 5:33).

The Small Plates were to meet a different profile. Nephi was instructed by the Lord God to “engraven many things upon them which are good in my sight for the profit of thy people” and “that which is pleasing unto God” (2 Nephi 5:30, 32). Nephi had earlier explained what he meant by “the things of God” and “things which are pleasing unto God” when he said: “For the fullness of mine intent is that I may persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham and the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob and be saved” (1 Nephi 6:3–5). For Nephi, that phrasing constitutes a meristic (abbreviated) version of the doctrine or gospel of Jesus Christ, which will be spelled out in its fullness only at the climax of his writing in 2 Nephi 31.18 But at this point he is ready to plunge into an account of the visualization of that gospel as given to Lehi and Nephi in the vision of the tree of life. In another paper, I show how these central chapters of First Nephi provide the foundation and visualization of the spiritual teachings and prophecies that are distributed throughout First and Second Nephi.19

At another point, Nephi explained that the Small Plates were made “for the special purpose that there should be an account engraven of the ministry of my people” (1 Nephi 9:3). Another explanation provides even more detail and nuance:

And after that I made these plates by way of commandment, I Nephi received a commandment that the ministry and the prophecies — the more plain and precious parts of them — should be written upon these plates, and that the things which were written should be kept for the instruction of my people, which should possess the land, and also for other wise [Page 110]purposes, which purposes are known unto the Lord. (1 Nephi 19:3)

The “other wise purposes … known unto the Lord” are usually interpreted to refer to an incident in the modern translation process which necessitated the insertion of the Small Plates translation as a replacement for the lost 116 pages of translation from the beginning of Mormon’s Gold Plates abridgement. The key point is that these Small Plates would preserve the prophecies and teachings “for the instruction” of the people. They may contain select bits of Nephite history to contextualize and support those teachings, but prophecies of Christ and God’s future dealings with Israel and the Gentiles and the teaching of the gospel and the plan of salvation will prove to be the clear focus of all of Nephi’s writings. The six stories that give First Nephi a historical cast are in fact carefully constructed into parallel chiastic sections designed to prove the decidedly spiritual thesis announced in chapter one:

But behold, I Nephi will shew unto you that the tender mercies of the Lord is over all them whom he hath chosen because of their faith to make them mighty, even unto the power of deliverance. (1 Nephi 1:20)20

Inspired by the mid-century writings of Jacques Derrida, literary specialists began to rethink reading and writing and produced studies relating authors, audiences, and narrative beginnings in the 1970s and 1980s. LDS writer Benjamin McGuire leveraged some of this work to interpret some of these passages in Nephi in his 2014 postmodernist reading of Nephi.21 Of particular relevance to this paper, McGuire discussed four “narrative beginnings” he had identified in Nephi’s writings. I see McGuire’s paper as a very helpful contribution to the larger project of interpreting Nephi’s Small Plates. Once the role of Hebrew rhetoric is identified and assessed in Nephi’s writings, I see numerous additional ways in which McGuire’s framework can produce valuable new insights. But that will fall outside the limited scope of this paper.

1 Nephi 1:1–3

Nephi launched his introduction of the Small Plates with the facts that he “was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father” and that he had received “a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of [Page 111]God.” This preface points us to the mental and spiritual profile of the Small Plates as discussed above. But he also brings in the material and physical aspects of metal record production:

| A |

I Nephi having been born of goodly parents, |

| B |

therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father. |

| A* |

And having seen many afflictions in the course of my days, |

| B* |

nevertheless having been highly favored of the Lord in all my days, … |

The alternating parallel lines of this opening construction simultaneously introduce the blessings of being born in Lehi’s family and the afflictions suffered during his life of service to the Lord in a negative contrast. They also introduce his qualifications for writing an important book in a positive pairing. First, he has been taught in the highest compositional arts known to the Jerusalem scribal schools. And second, he has been taught by the Lord directly. This latter point will be repeated and made more explicit as he continues:

| A |

yea, having had a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God, |

| B |

therefore I make a record of my proceedings in my days. |

| C |

Yea, I make a record in the language of my father, |

|

a which consists of the learning of the Jews |

|

|

b and the language of the Egyptians. |

|

| C* |

And I know that the record which I make to be true. |

| B* |

And I make it with mine own hand, |

| A* |

and I make it according to my knowledge.22 |

Nephi holds this small chiasm together with an inclusio that refers to his “great knowledge of the goodness and mysteries of God,” which in turn provides the basic motivation and justification for making this record. While the scribal skills he has developed in Jerusalem — mastery of the Egyptian language, the learning of the Jews (Hebrew rhetoric), and the ability to manufacture writing materials, including metal plates — are also listed here, we will see that his knowledge of the goodness and mysteries of God will come from his own visions and revelations, and not from his scribal training.

[Page 112]As Nephi later confirms in regard to the Large Plates, he personally made the “plates of ore” and engraved the record of his people upon those plates.23 Nephi has explicitly laid claim not only to the educated skills of writing, rhetoric, and foreign languages, but also to the material skills of producing metal plates and metal engraving. As several new studies of Ancient Near Eastern literacy have shown, this rare combination of intellectual and material skills could be obtained only through years of training in a scribal school and its workshop.24

1 Nephi 1:16–17

Nephi’s second explanation of the Small Plates says more about the internal rhetorical structure of First Nephi than it does about the spiritual profile of the larger Small Plates project itself and emphasizes a distinction between an account of Lehi’s proceedings and Nephi’s own account. This prepares us for the fact that First Nephi will be divided structurally between those two accounts and gives us a more fine-grained understanding of Nephi’s writing.

| A |

And now I Nephi do not make a full account of the things which my father hath written, |

| B |

for he hath written many things which he saw in visions and in dreams. |

| C |

And he also hath written many things which he prophesied and spake unto his children, |

| D |

of which I shall not make a full account. |

| D* |

But I shall make an account of my proceedings in my days. |

| C* |

Behold, I make an abridgment of the record of my father upon plates (SP) which I have made with mine own hands. |

| B* |

Wherefore after that I have abridged the record of my father, |

| A |

then will I make an account of mine own life. |

[Page 113]It would be reasonable to ask why these five sentences are not attached immediately to Nephi’s first explanation in verses 1–3, where they would have fit perfectly by expanding that first explanation. What we will now see is that this multiplication of explanations in First Nephi serves an important purpose in the rhetorical structure of that book. Because of their connection to and identity with each other, these explanations can be located in a series of chiasms to provide parallel elements for those chiasms and make their chiastic structures more recognizable. Note how these first two explanations provide parallel structure for the chiasm embedded in chapter one:

| a |

Nephi … the learning of his father |

(1) |

| b |

Nephi’s many afflictions |

(1) |

| c |

the goodness and mysteries of God |

(1) |

| d |

Nephi’s record … his own hands |

(2-3) |

| e |

Many prophecies |

(4) |

| f |

Lehi prays … with all his heart |

(5) |

| g |

Lehi saw and heard much … trembles |

(6) |

| h |

Lehi overcome with the Spirit |

(7) |

| i |

The heavens opened to Lehi |

(8) |

| j |

He sees God |

(8) |

| k |

He sees one descend |

(9) |

| j* |

He sees twelve |

(10) |

| i* |

The Lord opens a book to Lehi |

(11) |

| h* |

Lehi filled with the Spirit |

(12) |

| g* |

Lehi reads much … doom of Jerusalem |

(13) |

| f* |

Lehi’s whole heart filled … praises God |

(15) |

| e* |

Lehi records other prophecies |

(16) |

| d* |

Nephi’s record … his own hands |

(17) |

| c* |

the Messiah and redemption of the world |

(19) |

| b* |

Lehi’s afflictions |

(20) |

| a* |

Nephi’s teaching (learned from his father) |

(20) |

Any long, conceptual chiasm like this one needs to have multiple solid parallel elements indicated by the repetition of the same words — as we see here the repetitions in d-d*, f-f*, h-h*, combined with the strong apex structure in j-k-j*. Here we see Nephi’s first two explanations of the Small Plates located parallel to one another in the rhetorical structure of 1 Nephi 1 labeled d and d* above. Two of the other three explanations located in First Nephi will serve this same function in multiple overlapping chiasms, demonstrating the options a seventh-century [Page 114]bce Hebrew scribe had in distributing pieces of his composition in the creation of these rhetorical structures.25 The remaining three of Nephi’s explanations of the Small Plates will be taken up out of order to make it easier to track how they provide key anchors for his rhetorical structures in First Nephi.

1 Nephi 9: 1–6

The first edition of the Book of Mormon shows that the current chapter 9 constituted the closing sentences of Nephi’s original second chapter and brings the section labeled “Lehi’s Account” to a conclusion. This fourth explanation of the Small Plates and their relationship to the Large Plates is placed at the end of Lehi’s account to connect back to the opening sentences of that account — the first explanation of the Small Plates in the opening sentences of chapter one. The presentation of this fourth explanation will be followed below by an outline of the chiasm that structures Lehi’s account that it anchors. Nephi has inserted this fourth explanation between his description of the Tree of Life portion of Lehi’s great vision in chapter eight and the long list of other prophecies and teachings that Lehi passed on to his family at the time he reported that vision to them, as summarized by Nephi in chapter ten. This fourth explanation emphasizes the different role of the Large Plates as a comprehensive history of Lehi’s descendants and states only once the primary “special purpose” of the Small Plates as an account “of the ministry of my people.” The explanation begins with a simple chiasm that explains the purpose of the Large Plates, followed first by a trio of couplets articulating the different purposes of the Large and Small Plates and concluding with a pair of parallel couplets relating the Small Plates to the Lord’s unstated purposes:

And all these things did my father see and hear and speak as he dwelt in a tent in the valley of Lemuel, and also a great many more things which cannot be written upon these plates (SP).

| A |

And now as I have spoken concerning these plates (SP), |

| B |

behold, they are not the plates (LP) upon which I make a full account of the history of my people, |

| B* |

[Page 115]for the plates (LP) upon which I make a full account of my people I have given the name of Nephi; |

| A* |

wherefore they are called the plates of Nephi after mine own name. |

Ballast:26 And these plates (SP) also are called the plates of Nephi.

| A |

Nevertheless I have received a commandment of the Lord that I should make these plates (SP) |

| B |

for the special purpose that there should be an account engraven of the ministry of my people. |

| A* |

And upon the other plates (LP) |

| B* |

should be engraven an account of the reigns of the kings and the wars and contentions of my people. |

| A** |

Wherefore these plates (SP) are for the more part of the ministry, |

| B** |

and the other plates (LP) are for the more part of the reigns of the kings and the wars and contentions of my people. |

| A |

Wherefore the Lord hath commanded me to make these plates (SP) for a wise purpose in him, which purpose I know not. |

| B |

But the Lord knoweth all things from the beginning. |

| A* |

Wherefore he prepareth a way to accomplish all his works among the children of men. |

| B* |

For behold, he hath all power unto the fulfilling of all his words. |

Closer for Nephi’s chapter 2 and Lehi’s account: And thus it is. Amen.

Chiastic organization of Lehi’s account

In a 1980 publication I identified a complex rhetorical structure in First Nephi in which the twelve subsections of Lehi’s account match up with the twelve subsections of Nephi’s account in the second half of the book.27 These lists are included below. Most of the important discoveries about Hebrew rhetoric in the eighth and seventh centuries bce have [Page 116]been published after that date, and while I see that original article as a still-serviceable guide to the rhetorical structure of First Nephi, I can see many ways in which it can be expanded and enriched from the perspective of Hebrew rhetoric as now understood by Bible scholars. The proposed chiastic analysis of Lehi’s account follows here and shows the connection of Nephi’s first and fourth explanations for the Small Plates in that account (italicized). The parallel listings of the twelve elements of each account will then be introduced to show the roles of Nephi’s third and fifth explanations.

Chiasmus in 1 Nephi 1–9 (Lehi’s Account)

| A |

Nephi discusses his record, and he testifies it is true (1:1–3). |

| B |

Lehi’s early visions are reported, followed by his preaching and prophesying to the Jews (1:6–15, 18–20).28 |

| C |

Lehi takes his family into the wilderness (2:2–15). |

| D |

The Lord speaks prophecies to Nephi about Lehi’s seed (2:19–24). |

| E |

Lehi’s sons obtain the brass plates, and Nephi records the most striking example of the murmuring of his faithless brothers (3:2–5:16). |

| D* |

Lehi, filled with the Spirit, prophesies about his seed (5:17–19; 7:1). |

| C* |

Ishmael takes his family into the wilderness (7:2–22). |

| B* |

Lehi’s tree of life vision is reported, followed by his prophecies and preaching to Laman and Lemuel (8:2–38). |

| A* |

Nephi again discusses his record, and he records his testimony (9:1–6). |

This analysis recognizes that the story of retrieving the Brass Plates is the centerpiece of Lehi’s account, which emphasizes the critical role that record played in Lehi’s dispensation and its supreme importance to Lehi and Nephi, who, as trained scribes in the tribe of Manasseh, may even have been involved in its very recent production.29 Further, Nephi has framed the account of his father’s proceedings with two of [Page 117]his explanations of the nature and purpose of the full record of which it constitutes the first of three sections — the Small Plates.

Lehi’s Account Compared to Nephi’s Account

1 Nephi 19:1–6

This fifth explanation, coming near the end of the book of First Nephi, is the most comprehensive of the six that Nephi has distributed throughout his writings. In this passage, Nephi clearly states the sequence in which he received divine commandments to make records. The first must have come early on and led Nephi to make his Large Plates, which contained both the history of his people and the prophecies and revelations received by him and his father. He was then surprised by the second command received thirty years after leaving Jerusalem to make a another set of plates. He was then commanded to write “the ministry and the prophecies — the more plain and precious parts of them” on these Small Plates. These would “be kept for the instruction of my people” and “for other wise purposes … known unto the Lord.”

This fifth explanation begins with a parallel pair of triplets (or extended alternates) that explain the Large Plates as a predecessor to these Small Plates. This is followed by a second pair of parallel triplets focused on explaining the Small Plates and how they are distinguished in their content and usage from the Large Plates.

| A |

And it came to pass that the Lord commanded me, |

|

a wherefore I did make plates of ore (LP) |

|

|

b that I might engraven upon them (LP) the record of my people. |

|

| B |

And upon the plates (LP) which I made I did engraven the record of my father |

|

a and also our journeyings in the wilderness |

|

|

b and the prophecies of my father. |

|

| C |

And also many of mine own prophecies have I engraven upon them (LP). |

| A* |

And I knew not at that time which I made them that I should be commanded of the Lord to make these plates (SP). |

| B* |

Wherefore the record of my father and the genealogy of his forefathers and the more part of all our proceedings in the wilderness are engraven upon those first plates (LP) of which I have spoken. |

| C* |

[Page 118]Wherefore the things which transpired before that I made these plates (SP) are of a truth more particularly made mention upon the first plates (LP). |

| A |

And after that I made these plates (SP) by way of commandment, I Nephi received a commandment that the ministry and the prophecies — the more plain and precious parts of them — should be written upon these plates (SP), |

| B |

and that the things which were written should be kept for the instruction of my people, which should possess the land, |

| C |

and also for other wise purposes, which purposes are known unto the Lord. |

| A* |

Wherefore I Nephi did make a record upon the other plates (LP), which gives an account or which gives a greater account of the wars and contentions and destructions of my people. |

| B* |

And now this have I done and commanded my people that they should do after that I was gone and that these plates (SP) should be handed down from one generation to another or from one prophet to another until further commandments of the Lord. |

| C* |

And an account of my making these plates (SP) shall be given hereafter. And then behold, I proceed according to that which I have spoken; and this I do that the more sacred things may be kept for the knowledge of my people. |

Ballast: Nevertheless I do not write any thing upon plates save it be that I think it be sacred.

Nephi’s creativity in using the principles of Hebrew rhetoric is on display in many ways in this book, but none is more compelling than the way he uses his fourth and fifth explanations of the Small Plates in his parallel linkage of the twelve subsections in Lehi’s and Nephi’s accounts. In Table 1, these subsections are easy to connect — except for the puzzling partial reversal of the order in two instances. Subsections #3 and #5 of Lehi’s account match up with subsections #5 and #3 respectively in Nephi’s account. And then at the bottom of the table the same reversal recurs as subsections #9 and #11 of Lehi’s account match up respectively with #11 and #9 of Nephi’s account. This allows Nephi to use his fourth explanation twice in the rhetorical structure — first in parallel position with the first explanation in the chiastic organization of [Page 119]Lehi’s account — and then in parallel position with the fifth explanation which is placed well before the end of his own account.

Table 1. Lehi’s Account Compared to Nephi’s Account.

| 1 Nephi 1–9 (Lehi’s Account) | 1 Nephi 10–22 (Nephi’s Account) |

|---|---|

|

1. Nephi makes a record (or account) of his proceedings but first gives an abridgment of Lehi’s record (1:1–3, 16–17). 2. Nephi gives a brief account of Lehi’s prophecies to the Jews, based on visions he received in Jerusalem (1:5–15, 19). 3. Lehi is commanded to journey into the wilderness, and he pitches his tent in the valley he names Lemuel (2:1–7). 4. Lehi teaches and exhorts his sons, and they are confounded (2:8–15). 5. Nephi desires to know the mysteries of God; he is visited by the Holy Spirit and is spoken to by the Lord (2:16–3:1). 6. Lehi is commanded in a dream to send his sons for the brass plates of Laban (3:2–5:22). 7. In response to a command from the Lord, Lehi sends for Ishmael’s family (7:1–22). 8. They gather seeds of every kind (8:1). 9. Lehi reports to his sons the great vision received in the wilderness (8:2–35). 10. Lehi exhorts Laman and Lemuel, preaching and prophesying to them (8:36–38). 11. Nephi makes a distinction between the two sets of plates (9:1–5). 12. Nephi ends with a general formulation of his thesis and the formal punctuation: “And thus it is. Amen” (9:6). |

1. Nephi now commences to give an account of his proceedings, reign, and ministry but first “must speak somewhat of the things of [his] father, and … brethren” (10:1). 2. Nephi reports Lehi’s prophecies about the Jews, as given to Laman and Lemuel in the wilderness (10:2–15). 3. Nephi desires to see, hear, and know these mysteries; he is shown a great vision by the Spirit of the Lord and by an angel (10:17–14:30). 4. Nephi instructs and exhorts his brothers, and they are confounded (15:6–16:6). 5. Lehi is commanded to journey further into the wilderness, and he pitches his tent in the land he names Bountiful (16:9–17:6). 6. Nephi is commanded by the voice of the Lord to construct a ship (17:6–18:4). 7. In response to a command from the Lord, Lehi enters the ship and then sails (18:5–23). 8. Lehi’s family plants the seeds and reaps in abundance (18:24). 9. Nephi details the distinctions between the two sets of plates (19:1–7). 10. Nephi preaches and prophesies to Laman and Lemuel, his own descendants, and all Israel (19:7–21:26). 11. To explain Isaiah’s prophecies to his brothers, Nephi draws on the great vision given to him and Lehi (22:1–28). 12. Nephi ends with the highest formulation of his thesis, and with the formal punctuation: “And thus it is. Amen” (22:29–31). |

1 Nephi 6:1–6

This leaves Nephi’s third explanation of the Small Plates with no obvious role in the larger rhetorical structures. It comes immediately after and therefore juxtaposed to Lehi’s survey of the newly acquired Brass Plates and the genealogies contained therein. Nephi exploits this opportunity to make two points about his Small Plates in two short chiasms. The [Page 120]first explains why the Small Plates will not contain their genealogy — which would have been an expected initial component for any lineage history in the Ancient Near East. The second provides a clear and precise statement of the mission of the small plates: the fullness of his intent in this writing is to bring men to God and to the salvation he offers.

| A |

And now I Nephi do not give the genealogy of my fathers in this part of my record, |

| B |

neither at any time shall I give it after upon these plates (SP) which I am writing, |

| C |

for it is given in the record which has been kept by my father; |

| B* |

wherefore I do not write it in this work. |

| A* |

For it sufficeth me to say that we are a descendant of Joseph.30 |

| A |

And it mattereth not to me that I am particular to give a full account of all the things of my father, |

| B |

for they cannot be written upon these plates (SP), |

| C |

for I desire the room that I may write of the things of God. |

| D |

For the fullness of mine intent is that I may persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham and the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob and be saved. |

| C* |

Wherefore the things which are pleasing unto the world I do not write, |

| B* |

but the things which are pleasing unto God and unto them which are not of the world. |

| A* |

Wherefore I shall give commandment unto my seed that they shall not occupy these plates (SP) with things which are not of worth unto the children of men. |

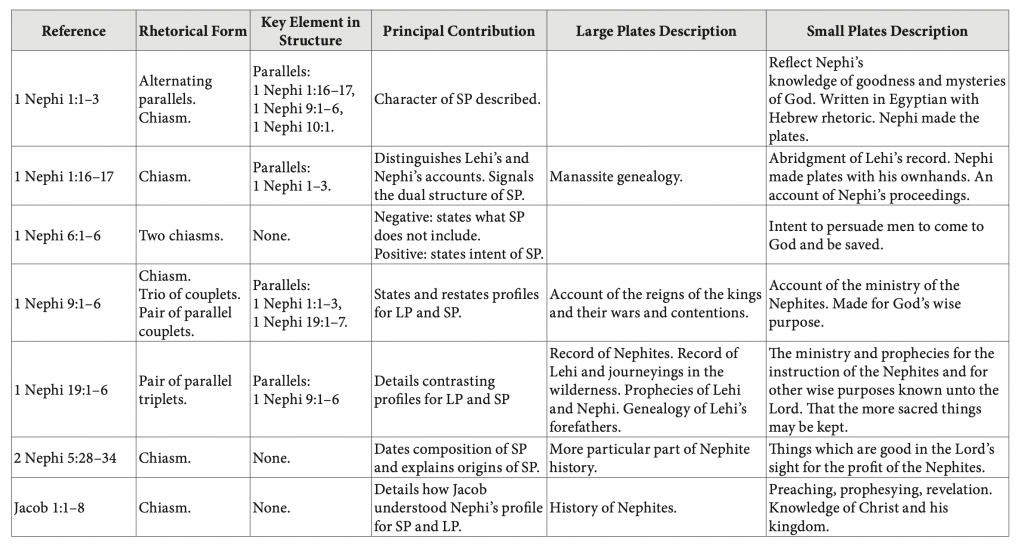

The characteristics of the seven passages are summarized in Table 2.

Conclusions

This paper provides a detailed review of the six passages in which Nephi refers to his second record directly and distinguishes its purpose from the first record. It also recognizes a seventh similar passage at the beginning of Jacob’s writings. All of these make it clear that Nephi and Jacob both understood the Large Plates to be a repository for a history of [Page 122]the people of Nephi, including their migrations, wars, and other events including preachings and revelations. The Small Plates were given a much narrower purpose by divine commandment. They should include only “a few of the most precious things” selected from the preaching, revelations, and prophecies. As it turned out, Jacob and his successors did not add that much to extend the Small Plates, and eighty percent of these plates would consist of Nephi’s writings. It is even more explicit in Jacob’s summary of Nephi’s instructions that the most precious things would be the prophecies and teachings about Christ that could be used to bring the people to him and be saved rather than rebelling against God — what Nephi referred to in his opening statement as his “knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God” (1 Nephi 1:1). And, finally, it has also been shown that Nephi had multiplied the passages in which he distinguished the two records in order to provide needed anchors for the rhetorical structures he had designed for his first section of the Small Plates (First Nephi).

[Page 121]Table 2. Summary of seven statements profiling the Small Plates (SP) and the Large Plates (LP).

Go here to see the 5 thoughts on ““Nephi’s Small Plates: A Rhetorical Analysis”” or to comment on it.