[Page 47]Abstract: In this article, I explore some of the opportunities and challenges that lie before us as we try to reach a better understanding of the prophetic corpus that has come to us from Joseph Smith. I turn my attention to a specific instance of these opportunities and challenges: the 21 May 1843 discourse on the doctrine of election, which Joseph Smith discussed in conjunction with the “more sure word of prophecy” mentioned in 2 Peter 1:19.

Recovering Lost Dimensions of Meaning

in the Records of the Restoration

Now that we enjoy an unparalleled ease of access to the original manuscripts of the history, translations, revelations, and teachings of Joseph Smith,1 we are in an ideal position to explore the many lost dimensions of ancient religion that we can see and appreciate because of what the Prophet restored. Unfortunately, however, as soon as we begin to explore in earnest, we realize that access to his papers addresses only the issue of transmission of his words, and accurate transmission “need in no way imply ‘understanding.’”2 For modern readers to understand the papers of Joseph Smith, some amount of translation must also be done, even for English–speakers.3

Hugh Nibley points out that a “translation must … be not a matching of dictionaries but a meeting of minds, for as the philologist William Entwistle puts it, ‘there are no ‘mere words’ … the word is [Page 48]a deed’; it is a whole drama with centuries of tradition encrusting it, and that whole drama must be passed in review every time the word comes up for translation.”4 Below, I will outline twelve interpretive and historiographical challenges that must be faced in order to achieve a better understanding of Joseph Smith’s words.

Interpretive Challenges

1. The challenge of replicating Joseph Smith’s range of experience. In an insightful presentation by John C. Alleman, he described several examples of difficulties that still plague translators when they are required to render the teachings of Joseph Smith in a form that can be understood by “every nation, and kindred and tongue, and people.”5 In the course of his discussion of specific issues in vocabulary, syntax, culture, scripture citations, and foreign phrases, Alleman summarized the one major proposition that underlies all translation:6 “namely, that one cannot translate that which one does not understand. … The problems [in translating the teachings of Joseph Smith require] … a range of experience equal to that which the Prophet himself had, almost, to understand some of his writings.”7

A range of experience equal to that which the Prophet himself had? This, the man whose mind8 “stretch[ed] as high as the utmost heavens, and search[ed] into and contemplate[d] the deepest abyss, and the broad expanse of eternity”— indeed, one who “commune[d] with God”!9 What greater range of experience could be imagined than that?

2. The challenges of decoding imagery and overcoming our lack of familiarity with scripture. Even if we thought ourselves capable of fully grasping the plain sense of Joseph Smith’s most straightforward statements, most of us will still struggle to decode his pervasive imagery, which is so often loaded with localisms, creative allusions, and scriptural wordplay.10 Moreover, the frequent allusions Joseph Smith made to scripture and other sources will never be recognized, let alone understood, unless we are familiar with these external texts ourselves.11 One of Joseph Smith’s frequent teaching methods was to take an obscure or misunderstood passage of scripture and unfold new meanings to his listeners, drawing on both his familiarity with an astonishing number of scriptural passages12 and also on the prophetic insights he had gained firsthand through divine revelation. Sadly, however, scriptures are not the staple of literary and religious life in our day that they were to those who lived in Joseph Smith’s time.[Page 49]

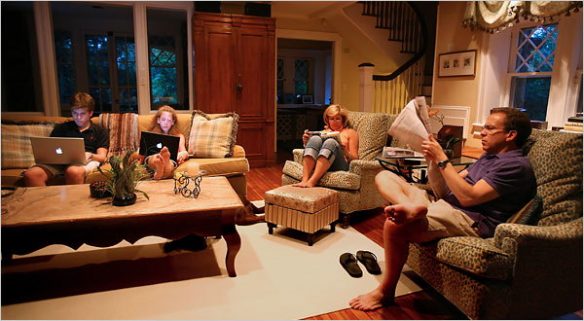

Figure 1. Nichole Bengiveno: “The Simses of Old Greenwich, Conn., gather to read after dinner. Their means of text delivery is divided by generation.”13

3. The challenges of vocabulary and reading skills. At the most basic level, many scriptural terms such as “endow,” “seal,” “mystery,” “key,” “sign,” “token,” “calling,” and “election” have significantly changed in meaning, connotation, and association since the early days of the Restoration.14 In some cases, the words have completely dropped out of our everyday vocabulary. Besides these challenges at the lexical level, some early evidence suggests that those of us who feed largely on today’s media may read differently than our ancestors.15 For one thing, we have become accustomed to a kind of reading that consists of facile skimming for rapid information ingestion — what the great Jewish scholar Martin Buber went so far as to term “the leprosy of fluency.”16 For another thing, even if one had the time and patience to read more reflectively, many today lack the capacity to follow the logic of passages that are longer than a sound bite. Complex descriptions or lines of argument are mentally processed as grab bags of simple, unordered, atomic associations rather than as linear structures that were carefully composed by divinely inspired authors of scripture to serve specific literary, expository, or revelatory purposes.17

4. The challenge of doctrinal ignorance. It cannot be doubted that our difficulties in grasping the larger logic of scripture — the logic that binds phrases and sentences together into coherent passages — are at least partly behind what Prothero calls a widespread “religious amnesia” that has dangerously weakened the foundations of faith.18 When scripture is consulted at all, it is too often “solely for its piety or its inspiring adventures”19 or its admittedly “memorable illustrations and [Page 50]contrasts” rather than the “deep memories” of spiritual understanding that provide context for the imagery and are woven throughout the stories themselves.20 Harold Bloom concludes that since the current “American Jesus can be described without any recourse to theology,” we have become, on the whole, a post-Christian nation.21 Similarly, Herberg characterized our national “faith in faith” as a “strange brew of devotion to religion and insouciance as to its content.”22 Little wonder that the teaching of the major doctrines of the Gospel, as centered in scripture, has become a significant emphasis in classroom teaching over in recent years.23

5. The challenge of personal revelation. According to Hugh Nibley, the written record of what the Prophet translated, revealed, and taught is a “means of helping those to understand who are unable to get the Spirit for themselves.”24 In other words, we might say that the revelatory corpus of Joseph Smith is intended to serve as a set of training wheels that aid readers to understand, through their own personal revelation,25 what “God [already] revealed”26 to the Prophet. Understanding what has already been revealed prepares us in turn to receive whatever additional revelation is needed on specific matters that concern our own lives and stewardships. In this connection, Elder Neal A. Maxwell once remarked: “God is giving away the spiritual secrets of the universe,” and then asked: “but are we listening?”27

6. The challenges of Joseph Smith’s reluctance to share sacred events publicly and of deliberately concealed meaning. A further difficulty that hinders our understanding of Joseph Smith’s words is his reluctance to share details of sacred events and doctrines publicly. Consider, for example, Joseph Smith’s description of the Book of Mormon translation process. While some of the Prophet’s contemporaries gave detailed descriptions of the size and appearance of the plates, the instruments used in translation, and the procedure by which the words of the ancient text were made known to him, Joseph Smith demurred when asked to relate such specifics himself, even in response to direct questioning in private company from believing friends.28 The only explicit statement we have from him about the translation process is his testimony that it occurred “by the gift and power of God.”29 More generally, Brigham Young referred to the fact that those who sat in Joseph Smith’s “secret councils year after year … heard [him] say thousands of things that the people have never yet heard.”30 Moreover, on at least one occasion — following the practice of Jesus when He taught in parables31 — the Prophet gave a sermon with a meaning that was deliberately concealed [Page 51]to all but a few of his listeners.32 All this leads one to wonder just how much we might be missing when we read the record of Joseph Smith’s teachings.33

7. The challenge of understanding the ancient context of scripture. Of course, all I have mentioned above is only the beginning of the challenge before us in trying to understand what Joseph Smith revealed and taught. Not only are we handicapped in our personal preparation to close the revelatory gap of prophetic experience with that of a nineteenth-century seer, we also live on the near side of a great historical divide that separates us from the religious, cultural, and philosophical perspectives of previous ages.34 Joseph Smith was far closer to this lost world than we are — not only because of his personal involvement with the recovery and revelatory expansion of ancient religion, but also because in his time many archaic traditions were still embedded in the language and daily experience of the surrounding culture.35 Margaret Barker describes the challenges this situation presents to contemporary students of scripture:

Like the first Christians, we still pray “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven,”36 but many of the complex systems of symbols and stories that describe the Kingdom are not longer recognized for what they are.37

It used to be thought that putting the code into modern English would overcome the problem and make everything clear to people who had no roots in a Christian community. This attempt has proved misguided, since so much of the code simply will not translate into modern English. … The task, then, has had to alter. The need now is not just for modern English, or modern thought forms, but for an explanation of the images and pictures in which the ideas of the Bible are expressed. These are specific to one culture, that of Israel and Judaism, and until they are fully understood in their original setting, little of what is done with the writings and ideas that came from that particular setting can be understood. Once we lose touch with the meaning of biblical imagery, we lose any way into the real meaning of the Bible. This has already begun to happen and a diluted “instant” Christianity has been offered as junk food for the mass market. The resultant malnutrition, even in churches, is all too obvious.38

Consistent with Barker’s observations, many observers have documented a worldwide trend toward a religious mindset that prizes [Page 52]emotion39 and entertainment40 as major staples of worship. Even when undertaken with evident sincerity, religious gatherings of this sort rarely rise above the level of a “weekly social rite, a boost to our morale,”41 with exhortations on ethics occasionally thrown in for good measure.

8. The challenge of applying ancient scripture to modern contexts. A factor that complicates the statement by Barker above is that Joseph Smith not only interpreted scripture by “enquiring” about the particulars of the situation which “drew out the answer”42 of a given teaching in its ancient context, but also, like Nephi, reshaped his interpretations in order to “liken them”43 to the situation of those living in the latter days. Indeed, on many occasions, the specifics of Joseph Smith’s interpretations of scripture and doctrinal pronouncements can be understood only with reference to current events in his life, among the community of the Saints, and in the world. Thus, Ben McGuire argues that in contrast to the traditional view that our job in reading scripture is simply to uncover an absolute, “true” meaning that was meant to be grasped by the original audience, Joseph Smith frequently “ignores the increasing gap between the cultural and societal contexts of the past and present, and re-inscribes scripture within the context of the present.”44 McGuire observes that Nephi’s reading strategy, like that of Joseph Smith, is quite foreign to the traditional way of thinking about scripture interpretation: “He is consistently re-fashioning his interpretation of past scripture through the lens of his present revelations, and the outcome is something that [might have been] … unrecognizable to the earlier, original audience.”45

9. The challenge of pragmatically adapting the language of scripture and revelation. Though Joseph Smith was careful in his efforts to render a faithful reading of scripture when he translated and interpreted, he was no naïve advocate of the inerrancy or finality of scriptural language.46 For instance, although in some cases his Bible translation attempted to resolve blatant inconsistencies among different accounts of the Creation or the life of Christ, as a general rule he did not attempt to merge the sometimes-divergent perspectives from different accounts of the same events into a single harmonized version. Of course, having multiple versions of these important stories should not be seen a defect or inconvenience. Differences in perspective between such accounts, and even seeming inconsistencies, composed “in [our] weakness, after the manner of [our] language, that [we] might come to understanding,”47 can be an aid rather than a hindrance to human comprehension, perhaps serving disparate sets of readers or diverse purposes to some advantage.

[Page 53]In translating the Bible, Joseph Smith’s criterion for the acceptability of a given reading was typically pragmatic rather than absolute. For example, after quoting a verse from Malachi in a letter to the Saints, he admitted that he “might have rendered a plainer translation.” However, he said that his wording of the verse was satisfactory in this case because the words were “sufficiently plain to suit [the] purpose as it stands.”48 This pragmatic approach is also evident both in the scriptural passages cited to him by heavenly messengers and also in his preaching and translations. In these latter instances, he often varied the wording of Bible verses to suit the occasion.49

Historiographical Challenges

10. The challenge of obtaining qualified and reliable scribes. If all I have described thus far were not enough, there is the reality “that almost all of what we have of Joseph Smith’s sayings and writings comes to us not through his own pen, but via scribes and recorders who could not possibly have been 100% accurate when they attempted to write down the Prophet’s words.”50 Consider that Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo sermons were neither written out in advance nor taken down by listeners verbatim or in shorthand as they were delivered. Rather, they were copied as fragmentary notes and reconstructions of his prose (sometimes retrospectively) by a small number of individuals, often, but not always, including one or more official recorders.51 Of the estimated 450 discourses the Prophet may have given throughout his public ministry, available sources “identify only about 250 discourses, and his published history only gives reasonably adequate summaries of only about one-fifth of these.”52

It was an almost impossible job for Joseph Smith to find qualified and reliable scribes, and to manage their frequent turnover: “More than two dozen persons are known to have assisted the Prophet in a secretarial capacity during the final fourteen years of his life. … Of these scribes, nine left the Church and four others died while engaged in important writing assignments.”53 The arduous culmination of the trial-and-error effort that eventually produced Joseph Smith’s History of the Church was successful only after eight previous attempts to write the history had been abandoned.54

11. The challenge of complex and divergent sources. Notes kept by various individuals were shared and copied by others.55 Later, as part of serialized versions of history that appeared in church publications, many (but not all) of the notes from such sermons were gathered,56 [Page 54]expanded, amalgamated, and harmonized; prose was smoothed out; and punctuation and grammar were standardized.57 Elaborations on the original notes were made not only to complete a thought but also to include additional material not now available in extant sources.58 Sometimes the wording of related journal entries from scribes and others was changed to the first person and incorporated into the History of the Church59 in order to fill gaps in the record, an accepted practice at the time.60 Unfortunately, this approach masks the provenance of sources and the hands of multiple editors within the finished manuscript.

Over the years, various compilations have drawn directly from various editions of the History of the Church61 while, more recently, transcriptions of contemporary notes (including sources that were unavailable to historians who produced the standard amalgamated versions) also have been collected and published.62 In addition, translations of these accounts into different languages has sometimes exposed new difficulties that required creative solutions.63

12. The challenge of assessing the reliability of a given teaching of Joseph Smith. An important point in assessing the reliability of a given teaching of Joseph Smith is that while each of the published accounts of the Prophet’s Nauvoo sermons has been widely used to convey his teachings to church members on his authority, none of these were reviewed by him personally.64 Moreover, not quite two hundred years after these sermons were delivered, multiple variants in their content and wording — none of which completely reflect the actual words spoken — are in common circulation. In some cases, imperfect transcriptions of Joseph Smith’s words led to misconstruals of doctrine by early Church members and, in consequence, have had to be corrected explicitly by later Church leaders. One need look no further than the March 2014 edition of the Ensign for a valuable apostolic correction of such a misunderstanding.65 In light of historical circumstances, it is easy to see how significant divergences in our understanding of Joseph Smith’s teachings have sometimes happened, even in the best case where like-minded scribes recorded events more or less as they occurred, doing the best they could to preserve the original words of the Prophet. This phenomenon also helps explain the great lengths that Joseph Smith went to, in compliance with the commandments of the Lord, in order to preserve an accurate written record of the doings of his day.66

With these considerations in mind, I will undertake a close look at the 21 May 1843 discourse of Joseph Smith. The detailed accounts of that sermon come to us from Elder Willard Richards67 (the keeper of Joseph [Page 55]Smith’s journal), from the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook,68 and from the expanded and polished version prepared for publication by church historians in the 1850s.69 Shorter summaries of portions of the sermon are also provided by Franklin D. Richards, James Burgess, Wilford Woodruff, and Levi Richards.70 In addition to these accounts, I will also quote relevant passages from the Prophet’s discourses on other occasions, including material from the diaries of Wilford Woodruff71 and William Clayton.72

Synopsis of Joseph Smith’s 21 May 1843 Discourse:

“The More Sure Word of Prophecy”

On the morning of Sunday, 21 May 1843, Joseph Smith “pressed his way through the crowd”73 to the stand on the floor of the unfinished Nauvoo temple.74 After the congregation sang, he read the text he had selected as the subject of his discourse: the first chapter of 2 Peter. After a prayer by William Law, more singing, and a few introductory remarks, he opened his sermon.

What Could Be “More Sure” Than Hearing the Voice of God Bearing Testimony of His Son?

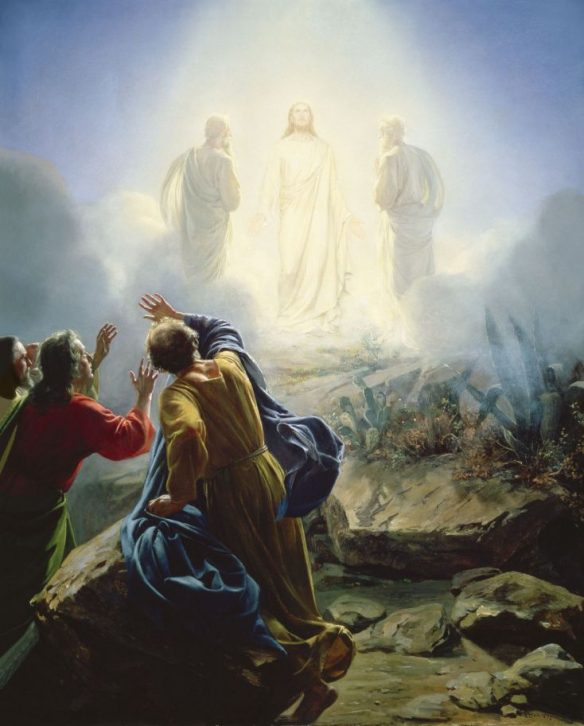

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: we have a more sure word of prophecy. whereunto you do well to take heed — as unto a light that shineth in a dark place.76 We were eyewitnesses of his maje[s]ty and heard the voice of his excellent glory — &. what could be more [p. [212]] sure? transfigu[re]d on the mou[n]t &c what could be more sure? Divines have been quarreeelig [quarreling] for ages about the meaning of this.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: “We have a more sure word of prophecy, whereunto you do well to take heed, as unto a light that shineth in a dark place.77 We were eye witnesses of his majesty and heard the voice of his excellent glory.”78 And what could be more sure? When He was transfigured on the mount,79 what could be more sure to them? Divines have been quarreling for ages about the meaning of this.

Original Notes in Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:80 we were eye witnesses of his Majesty we have also a more sure word of Prophecy.[Page 56]

The first topic taken up by the Prophet in this discourse is the meaning of the reference in 2 Peter 1:19 to the “more sure word of prophecy.” Continuing his effort to “stir … up” the Saints “in remembrance of these things” (vv. 13, 12), Peter reminded his readers of his firsthand experience at the Mount of Transfiguration. The overall scriptural account is cryptic, and translators have struggled particularly with the reference to the “more sure word of prophecy” in verse 19 — a “crux interpretum” for the entire book according to Jerome Neyrey.81

On the Mount of Transfiguration, Peter and his companions had become “eyewitnesses of [the] majesty”82 of the glorified Jesus Christ and had heard the voice of God the Father declare: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”83 Joseph Smith asked his hearers, “What could be more sure” than that? The Prophet will give the answer to that question near the end of his sermon.

The “more sure word of prophecy” is a topic to which the Prophet returned again and again, especially in the last two years of his life.84 He had made the first chapter of 2 Peter the subject of a sermon the previous Sunday, 14 May 1843,85 and preached on it again to a different audience on 17 May.86 He elaborated on the same principles and doctrines on 1387 and 27 August 184388 and again on 10 March89 and 12 May90 1844. Since [Page 57]our record of his sermons is incomplete, he may have addressed the topic on additional occasions as well. His discourse of the 21 May 1843 was not intended merely as an exposition of doctrine. Rather, at its heart was an urgently enjoined plea for the Saints to “go forward and make [their] calling and … election91 sure”92 “for in this way entry into the eternal kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ will be richly added to you.”93

Polishing the Rough Stone

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: rough stone roling down hill.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: I am like a huge, rough stone rolling down from a high mountain; and the only polishing I get is when some corner gets rubbed off by coming in contact with something else, striking with accelerated force against religious bigotry, priestcraft, lawyer-craft, doctor-craft, lying editors, suborned judges and jurors, and the authority of perjured executives, backed by mobs, blasphemers, licentious and corrupt men and women—all hell knocking off a corner here and a corner there. Thus I will become a smooth and polished shaft in the quiver94 of the Almighty, who will give me dominion over all95 and every one of them, when their refuge of lies shall fail, and their hiding place shall be destroyed,96 while these smooth-polished stones with which I come in contact become marred.97

Notes from a Sermon Recorded on 11 June 1843 in Joseph Smith’s Diary:98 I a rough stone. The sound of the hammer and chisel was never hea[r]d on me, nor never will be. I desire the learning & wisdom of heaven alone

Notes from a Sermon of Heber C. Kimball recorded by Wilford Woodruff on 9 September 1843:99 We are not Polished stones like Elder Babbit Elder Adams, Elder Blakesley & Elder Magin &c. But we are rough Stones out of the mountain, & when we roll through the forest & nock the bark of from the trees it does not hurt us even if we should get a Cornor nocked of occasionally. For the more they roll about & knock the cornors of the better we are. But if we were pollished & smooth when we get the cornors knocked of it would deface us.

[Page 58]This is the Case with Joseph Smith. He never professed to be a dressed smooth polished stone but was rough out of the mountain & has been rolling among the rocks & trees & has not hurt him at all. But he will be as smooth & polished in the end as any other stone, while many that were so vary poliched & smooth in the beginning get badly defaced and spoiled while theiy are rolling about.

The self-characterization of Joseph Smith as a “rough stone rolling” was made famous by the title of Richard Bushman’s biography of the Prophet.100 Starting out as a rough stone was a badge of honor in the rough culture in which Joseph Smith was raised101 — and the fact no one but God could take credit for the polishing only added to that honor: “The sound of the hammer and chisel was never hea[r]d on me, nor never will be. I desire the learning & wisdom of heaven alone.”

The comparison of the polishing of a rough stone to the moral education of Joseph Smith would have been familiar not only to students of the Bible but also to fellow Freemasons in the Prophet’s audience. According to Masonic historian W. Kirk MacNulty:102

The Rough Ashlar is a stone fresh from the quarry that must be cut to the appropriate shape before it can be placed in the building. It represents the Apprentice who has started his journey, and who must work to improve himself.

The Perfect Ashlar is a stone that has been cut and polished to its proper form and is ready to be placed in the building. It represents the Apprentice who has completed his work and is ready to advance to the Second Degree.

As mentioned above, Joseph Smith’s version of the thought emphasizes that his polishing was not so much the result of efforts at ordinary self-improvement as it was of “the learning & wisdom of heaven.” This is consistent with the biblical ethos of Exodus 20:25:103 “And if thou wilt make me an altar of stone, thou shalt not build it of hewn stone: for if thou lift up thy tool upon it, thou hast polluted it.” The imagery is also reflected in Daniel’s interpretation of the vision of the stone that was “cut out of the mountain without hands”104 and Jesus’ prophecy that contrasted the “temple that is made with hands” (i.e., Herod’s temple) to the temple that would be made “within three days … without hands”105 (i.e., Jesus’ resurrected body).

Why would one want to polish stones for building purposes before they are brought out of the mountain quarries and onto the construction [Page 59]site?106 An answer is provided in the description of how such stones were to be prepared for use in Solomon’s Temple:107

And the house, when it was in building, was built of stone made ready before it was brought thither: so that there was neither hammer nor axe nor any tool of iron heard in the house, while it was in building.

The brevity of Elder Richards’ note on this passage suggests that he may have heard similar comments on other occasions and only required a few words to remind him of the gist.108 Note the accounts of similar imagery used on 11 June and 9 September 1843 as given above.

“By Virtue of the Knowledge of God in Me”

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: 3 grand secrets lying in this chapter which no man can dig out. which unlocks the whole chapter.

what is writtn are only hints of things which ex[is]ted in the prophets mind. which are not written. concer[n]ing eternal glory.

I am going to take up this subj[e]ct by virtue of the knowledge of God in me. — which I have received fr[o]m heaven. [p. [213]]

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: There are three grand secrets lying in this chapter, [2 Peter 1] which no man can dig out, unless by the light of revelation, and which unlocks the whole chapter as the things that are written are only hints of things which existed in the prophet’s mind, which are not written109 concerning eternal glory.

I am going to take up this subject by virtue of the knowledge of God in me, which I have received from heaven.

Original Notes in Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:110 Now brethren who can explain this no man be [but] he that has obtained these things in the same way that Peter did. Yet it is so plain & so simple & easy to be understood that when I have shown you the interpretation thereof you will think you have always Known it yourselves — These are but hints at those things that were revealed to Peter, and verily brethren there are things in the bosom of the Father, that have been hid [Page 60]from the foundation of the world, that are not Known neither can be except by direct Revelation

In light of the Prophet’s reticence to share all the details of his sacred experiences openly, he was certainly commenting as much on his personal practice as he was on Peter’s when he explained that “what is written [is] only hints of things which existed in the prophet’s mind.”111 The secrets hinted at by Peter in this chapter could be discovered by no man except through direct revelation. Thus, of necessity, Joseph Smith would explain the passage “by virtue of the knowledge of God in me. — which I have received fr[o]m heaven.”

No doubt, the Prophet saw the “hints” given in this chapter as pointing to knowledge and keys received by Peter, James, and John on the Mount,112 including the firm “promise from God,” received personally for themselves, that they should “have eternal life. That is the more sure word of prophecy.”113 The comment that these things were “hid from the foundation of the world” reinforces the idea that these hints had to do with the highest blessings of the priesthood.114

“The Opinions of Men … Are to Me as the Crackling of the Thorns Under the Pot”

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: the opinions of men. so far as I am possessed concerned. are to me as the crackling of the thorns under the pot.115 or the whistle[n]g of the wind, Columbus and the eggs. —

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: The opinions of men, so far as I am concerned, are to me as the crackling of thorns under the pot,116 or the whistling of the wind. I break the ground; I lead the way like Columbus when he was invited to a banquet, where he was assigned the most honorable place at the table, and served with the ceremonials which were observed towards sovereigns. A shallow courtier present, who was meanly jealous of him, abruptly asked him whether he thought that in case he had not discovered the Indies, there were not other men in Spain who would have been capable of the enterprise? Columbus made no reply, but took an egg and invited the company to make it stand on end. They all attempted it, but in vain; whereupon he struck it upon the table so as to break one end, and left it standing on the broken [Page 61]part, illustrating that when he had once shown the way to the new world nothing was easier than to follow it.

Original Notes Recorded from a Sermon Delivered on 17 May 1843 in Wilford Woodruff’s Diary:117 I will make every doctrine plain that I present & it shall stand upon a firm bases And I am at the defiance of the world for I will take shelter under the broad shelter cover of the wings of the work in which I am ingaged. It matters not to me if all hell boils over. I regard it ownly as I would the Crackling of thorns under a pot.118

Expressing his disregard for the skepticism of unbelievers about his mission and teachings, Joseph Smith compared their views to “the crackling of the thorns under the pot” or “the whistle[n]g of the wind.” “By virtue of the knowledge of God in [him],” he was in a position to lead out in his teachings rather than follow the shallow opinions of others.

As with the previous reference to the rough stone rolling, church historians confidently expanded the brief note about “Columbus and the eggs” into a polished version of the well-known anecdote.119

Ladder and Rainbow

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: Ladder and rainbow.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: Paul ascended into the third heavens,121 and he could understand the three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder122 — the telestial, the terrestrial, and the celestial glories or kingdoms,123 where Paul saw and heard things which were not lawful for him to utter.124 I could explain a hundred fold more125 than I ever have of the glories of the kingdoms manifested to me in the vision,126 were I permitted, and were the people prepared to receive them.127

The Lord deals with this people as a tender parent128 with a child, communicating light and intelligence and the knowledge of his ways129 as they can bear it.130 The inhabitants of this earth are asleep;131 they know not the day of their visitation.132 The Lord hath set the bow in the cloud133 for a sign that while it shall be seen, seed time and harvest, summer[Page 62]

and winter shall not fail; but when it shall disappear, woe to that generation, for behold the end cometh quickly.134

Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:135 There are some things in my own bosom that must remain there. If Paul could say I Knew a man who ascended to the third heaven & saw things unlawful for man to utter, I more. [Note that this passage occurs at a later place in the discourse within the Coray notebook than it does in the church historians’ expansion. More on this below.]

Original Notes Recorded from a Sermon Delivered on 17 May 1843 in William Clayton’s Diary:136 Paul had seen the third heavens and I more.

Original Notes Recorded from a Sermon Delivered on 11 June 1843 in Joseph Smith’s Diary:137 I wou[l]d make you think I was climbi[n]g a ladder when I I was climbing a rainbow.

Original Notes Recorded from a Sermon Delivered on 10 March 1844 in Joseph Smith’s Diary:138 The bow has been seen in the cloud & in that year that the bow is seen seed time [Page 63]and harvest will be. but when the bow ceases to be seen look out for a famine. [5 lines blank] [p. [30]]

The sense of the words “ladder and rainbow” might be something like the statement made by Joseph Smith few weeks later: “I wou[l]d make you think I was climbi[n]g a ladder when I I was climbing a rainbow.” The point of the allusion is unclear, however Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers infer from the context of the 11 June discourse that Joseph Smith was “commenting on the misleading use of theological terms.”139 With respect to the conjectured application of a similar phrase during the 21 May sermon, Andrew Ehat and Lyndon Cook see it as an anecdotal comment on the general “theme of reluctance — the reluctance of others to accept Joseph Smith’s teachings,”140 as also expressed in the previous anecdotes of the rough stone rolling and Columbus and the egg. A third possibility is raised by Ben McGuire, who matches up Joseph Smith’s reference with a statement by Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), the Congregationalist theologian:141

Part of this bow is on earth, and part in heaven, so it is with the church. The bow gradually rises higher and higher from the earth towards heaven, so the saints from their first conversion are travelling in the way towards heaven, and gradually climb the hill, till they arrive at the top. So this bow in this respect is a like token of the covenant with Jacob’s ladder, which represented the way to heaven by the covenant of grace, in which the saints go from step to step, and from strength to strength, till they arrive at the heavenly Zion.

Comments McGuire: “I don’t know if Joseph Smith was aware of the material of Edwards, and so I cannot say with any sort of conviction that this was the case. But it makes me wary of the idea that Joseph was simply ‘commenting on the misleading use of theological terms’ — especially in a context where we can trace many of these ideas and anecdotes and allusions to existing contemporary material and sources.”142

Regardless of exactly how this phrase should be understood, it appears that later church historians were incorrect in reshaping and expanding “ladder and rainbow” into the passage that was published in Joseph Smith’s history. In further support of the view that the historians’ expansion failed to capture the intent of the Prophet is that “ladder” and “rainbow” seem to be joined as a single idea in the original notes, which contradicts their later rendering as two disjointed — and seemingly out-of-place — paragraphs. But if it is true that the brief note was incorrectly [Page 64]fleshed out by later church historians, where did the additional material they used for the published version come from?

With respect to the paragraph that expands on the mention “rainbow,” a plausible conjecture is that church historians borrowed, not only from their memories of the 21 May discourse, but also from Joseph Smith’s prophetic statements about the sign of the rainbow in his 10 March 1844 discourse. Though the passage does not really fit the context of the 21 May 1843 discourse where it was placed, it seems consistent with the more extensive notes taken on the later occasion.

With respect to the paragraph that expands on the “ladder,” parallels to the statements about Paul’s and Joseph Smith’s ascensions in the account of the 21 May sermon are recorded in the Coray notebook and in the record of William Clayton for 17 May. In addition, sentiments similar to Joseph Smith’s statements regarding how little of what he knew he was able to share with the Saints can be found elsewhere in his Nauvoo teachings143 as well as in the Book of Mormon.144

However, there is one idea in this same paragraph that has no other direct attestation elsewhere in the teachings of Joseph Smith, namely the assertion that Paul “could understand the three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder — the telestial, the terrestrial, and the celestial glories or kingdoms.”145 How did the historians come up with this statement? Three possibilities come to mind:

- The statement was made up by later historians from whole cloth. This possibility seems remote since nothing in its immediate context would have required inventing a statement to this effect, either to complete the rest of the thought or to enhance its readability. Had the historians simply left the idea out, no one would have noticed its absence. Moreover, according to Elder George A. Smith, inventing new material was something that he and his fellow historians strenuously avoided doing — and indeed there is nowhere else in this sermon where the polished prose they provided is not plausible. Of his work on the History of the Church, Elder Smith said that “the greatest care has been taken to convey the ideas in the Prophet’s style as near as possible; and in no case has the sentiment been varied that I know of; as I heard the most of his discourses myself, was on the most intimate terms with him, have retained a most vivid recollection of his teachings.” In addition, Elder Smith felt his own careful editorial work was enhanced by [Page 65]promised inspiration146 in his calling and the fact that he verified his work by reading each compiled discourse with members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve, many of whom had also heard the original discourses.147 Moreover, we know that Joseph Smith used related imagery about a ladder on at least two other occasions.148 Finally, this statement, if authentic, it would be — along with the “rough stone rolling” anecdote — a second direct instance of wordplay in the same discourse that would have been recognized by the Prophet’s fellow Freemasons. Although Freemasonry is not a religion and, in contrast to Latter-day Saint temple ordinances, does not claim saving power for its rites,149 within the first degree of Masonry, the ladder is also said to have “three principal rounds, representing Faith, Hope, and Charity,” which “present us with the means of advancing from earth to heaven, from death to life — from the mortal to immortality.”150 Similar to the reconstructed statement of Joseph Smith, Freemasonry correlates these three “principal rounds” with three different worlds or states of existence, beginning with the physical world and ending with the Heavens. All these culminate in a fourth level, associated with “Divinity.”151 Putting ancient imagery in Masonic terms already familiar to many of the early Saints would have served a pragmatic purpose, favoring their acceptance and understanding of specific aspects of the scriptural idea better than if a new and foreign vocabulary had been introduced.152

- The statement was derived from something Joseph Smith said elsewhere at one time or another. This possibility seems more plausible than the previous option. Indeed, as a prime example of such a practice, the expanded prose associated with the “rainbow” arguably was created in part from material the historians found in the 10 March 1844 sermon. But if Joseph Smith’s teaching about the ladder and the three kingdoms did originate elsewhere, the question remains, from where did it come?

- The statement was derived from something Joseph Smith said elsewhere within the 21 May 1843 sermon. This is, of course, a more specific version of the alternative just described, so the arguments in favor there also support this third [Page 66]possibility. I believe that the best explanation for the origin of the “ladder” material is that it was erroneously transposed and then expanded, along with related material about Paul’s vision, from a later portion of the 21 May 1843 sermon to its current, earlier position. The idea of such a transposition becomes all the more believable in the realization that in the symbolic vocabulary of many ancients the rainbow was no less a means of heavenly ascent than the ladder153 — perhaps making Joseph Smith’s statement on confusion between the “ladder and rainbow” more than just a frivolous comparison. Specific evidence supporting a mistaken transposition of material is found in the Coray Notebook, which was not accessible to the church historians when they expanded Elder Richards’ notes.154 The reference therein, regarding Paul’s visit to the third heavens, occurs at a later point in the record of the sermon than it does in the historians’ expanded version of this material. Moreover, in the Coray account, at the very point in the sermon corresponding to the mention of Paul’s visit to the third heavens, there seems to be a gap in the account of Elder Richards.155 It seems plausible that one of the historians, remembering Joseph Smith’s statements about Paul’s visit and Jacob’s ladder and erroneously associating it with the cryptic reference to “ladder” in Elder Richards’ brief notes, could have inserted the expanded prose in the wrong place. Additionally, although the material in Coray’s Notebook parallels some of the material in historians’ version,156 it could not have been a source for it. Thus, the Coray notes provide independent corroboration both for a significant part of the gist of the expansion as well as for where it should have been located in the polished version of the sermon.

Elsewhere, I discuss in more detail the logic of equating of the three kingdoms of glory with the “three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder,”157 an idea which now appears less likely to have been made up from whole cloth by later church historians. However, for now let’s turn our attention to another ladder, Peter’s so-called “ladder of virtues,” that appears as part of the next passage from Joseph Smith’s 21 May 1843 sermon.[Page 67]

Peter’s “Ladder of Virtues”

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: like precious faith with us … — add to your faith virtue &c … another point after having all these qualifictins [qualifications] he lays this injutin [injunction]. — but rather make your calling & election sure — after adding all. this. virtue knowledge &. make your cal[l]ing &c Sure. — what is the secret, the starting point. according as his divine power which hath given unto all things that pertain to life & godliness. [p. [214]]

how did he obtain all things? — th[r]ough the knowledge of him who hath calld him. — there could not any be given pertain[in]g to life & knowledge & godliness without knowledge

wo wo wo to the Ch[r]istendom. — the divine & priests; &c — if this be true.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: Contend earnestly158 for the like precious faith159 with the Apostle Peter “and add to your faith virtue,” knowledge, temperance, patience, godliness, brotherly kindness, charity; “for if these things be in you, and abound, they make you that ye shall neither be barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ.”160 Another point, after having all these qualifications, he lays this injunction upon the people “to make your calling and election sure.”161 He is emphatic upon this subject — after adding all this virtue, knowledge, etc.,162 “Make your calling and election sure.”163 What is the secret — the starting point? “According to his divine power hath given unto us all things that pertain unto life and godliness.”164 How did he obtain all things? Through the knowledge of Him who hath called him.165 There could not anything be given, pertaining to life and godliness,166 without knowledge.

Original Notes in Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:167 The Apostle says, unto them who have obtained like precious faith with us the apostles through the righteousness of God & our Savior Jesus Christ, through the knowledge of him that has called us to glory & virtue add faith virtue &c. &c. to godliness brotherly kindness — Charity — ye shall neither be barren or unfruitful in the Knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. [Page 68]He that lacketh these things is blind — wherefore the rather brethren after all this give diligence to make your calling & Election Sure Knowledge is necessary to life and Godliness. wo unto you priests & divines, who preach that knowledge is not necessary unto life & Salvation. Take away Apostles &c. take away knowledge and you will find yourselves worthy of the damnation of hell.

The list of personal qualities from 2 Peter 1:3–11 discussed by the Prophet have long been suspected by scholars such as Käsemenn to be a “clear example of Hellenistic, non-Christian thought insidiously working its way into the New Testament.”168 Nowadays, however, this passage of scripture is generally accepted as “fundamentally Pauline”169 and, hence, thoroughly consonant with the ideas of early Christianity. The emphasis of these verses is on the finishing and refining process of sanctification, not the initiatory process of justification.170

2 Peter 1:4 sounds the keynote of the biblical list of the personal qualities of the perfected disciple, reminding readers of the “exceeding great and precious promises” that allow them to become “partakers [= Greek koinonos, ‘sharer, partaker’] of the divine nature.” The New English Bible captures the literal sense of this latter phrase: namely, the idea is that the Saints may “come to share in the very being of God.”171 Unlike the Latter-day Saints, who are comfortable with the idea of sharing “the very being of God,” contemporary Eastern Orthodox proponents of the doctrine of theosis are wary of the straightforward interpretation of “divine nature” in its original context. They are quick to clarify their narrower reading of the passage: “We are gods in that we bear His image, not His nature [i.e., His essence].”172 That said, apart from this important ontological difference, there are many similarities between the Eastern Orthodox doctrine of theosis and LDS teachings about exaltation, as Catholic scholar Jordan Vajda has so competently detailed.173

To those in whom the qualities of divine nature “abound” there comes the fulfillment of a specific “promise”: namely, that “they shall not be unfruitful in the knowledge of the Lord.”174 In other words, according to Joseph Smith’s exposition of Peter’s logic as given above, the additional “knowledge of the Lord” that disciples will receive — after they have qualified themselves through the cultivation of all these virtues and after they have entered into God’s presence — will ultimately make their “calling and election sure” so that they may “obtain all things.”

[Page 69]Significantly, the qualities, to which Christian disciples are exhorted to give “all diligence,”175 are not presented in 2 Peter 1 as a randomly assembled laundry list but rather as part of an ordered progression leading to a culminating point.176 These qualities have been structured into a rhetorical form called sorites, climax, or gradatio177 — a form that is not uncommon in Hellenistic, Jewish, and Christian literature. Harold Attridge explains the ladder-like property of the personal qualities given in lists of this type: “In this ‘ladder’ of virtues, each virtue is the means of producing the next (this sense of the Greek is lost in translation). All the virtues grow out of faith, and all culminate in love.”178 Joseph Neyrey observes that the Christian triad of faith, hope, and charity in 2 Peter 1:5–7 “forms the determining framework in which other virtues are inserted” in such lists.179 The table below summarizes key words in scriptural exemplars from Paul, Peter, and Doctrine and Covenants 4 that illustrate this idea:

|

Romans 5:1–5 |

2 Peter 1:5–7 |

D&C 4:6 |

|

faith |

faith |

faith |

|

virtue |

virtue |

|

|

peace |

knowledge |

knowledge |

|

temperance |

temperance |

|

|

hope [patience, experience]180 |

patience, godliness |

patience |

|

brotherly kindness |

brotherly kindness, godliness |

|

|

love |

charity |

charity |

|

humility, diligence |

Though some elements of the three lists differ,181 the reward of divine fellowship for disciples is the same. In 2 Peter 1:4, 8, and 10, they are promised that they will become “partakers of the divine nature,” that they will ultimately be fruitful “in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ,” and in this way, according to Joseph Smith’s reading, will have made their “calling and election sure.” In Romans 5:2, they are told that they will “rejoice in hope of the glory of God.” This means that they can look forward with glad confidence, knowing that they “will be able to share in the revelation of God — in other words, that [they] will come to know Him as He is.”182 D&C 4:7 states the same truths by echoing the words of the Savior: “Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall [Page 70]find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you”183 — a threefold promise that Matthew Bowen correlates to faith, hope, and charity. He notes that “‘ask’ and ‘seek’ correspond to the Hebrew verbs sh’l and bqsh, which were used to describe ‘asking for’ or ‘seeking’ a divine revelation, often in a temple setting,”184 and Jack Welch has argued that the symbolism of knocking is likewise best understood “in a ceremonial context.”185 It should be added, however, that temple ordinances foreshadow actual events in the life of faithful disciples who endure to the end.186

The expansion of 2 Peter’s list of virtues within section 4 of the D&C warrants further discussion. It is worth noting that the “three principal rounds” of the ladder — namely, faith, hope, and charity/love — are specifically highlighted in verse 5, and then repeated in the same order as part of the longer list of virtues given in verse 6. Intriguingly, the list of eight qualities found in 2 Peter 1 is expanded in D&C 4 to ten in number.187 In an insightful article, John W. Welch has shown how the number ten in the ancient world — which conveys the idea of perfection, especially divine completion — relates to human ascension into the holy of holies or highest degree of heaven:188

“The rabbinic classification of the ten degrees of holiness, which begins with Palestine, the land holier than all other lands, and culminates in the most holy place, the Holy of Holies, was essentially known in the days of High Priest Simon the Just, that is, around 200 bce.”189 Echoing these ten degrees on earth were ten degrees in heaven. In the book of 2 Enoch, Enoch has a vision in which he progresses from the first heaven into the tenth heaven, where God resides and Enoch sees the face of the Lord, is anointed, given clothes of glory, and is told “all the things of heaven and earth.”190 …

Kabbalah, a late form of Jewish mysticism, teaches that the ten Sefirot were emanations and attributes of God, part of the unfolding of creation, and that one must pass through them to ascend to God’s presence.191

Though it is true that no explicit mention is made in the Bible of the performance of rites inculcating this divine pathway of virtues, it is equally true that a lecture based on 2 Peter 1:3–11 would not in the least be out of place as a summary of progression through LDS temple ordinances.192

[Page 71]

Salvation Through Being Sealed Up Unto Eternal Life and Receiving the Key of the Knowledge of God

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: salvation. is for a man to be seve[r]ed [possibly “saveed” [saved]193] from all his enemies. — until a man can triumph over death. he is not saved. knowlidge will do this.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: Salvation is for a man to be saved from all his enemies;194 for until a man can triumph over death,195 he is not saved. A knowledge of the priesthood alone will do this.196

Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:197 Knowledge is Revelation hear all ye brethren, this grand Key; Knowledge is the power of God unto Salvation.

What is salvation. Salvation is for a man to be Saved from all his enemies even our last enemy which is death and for David Saith, “and the Lord Said unto my Lord ‘Sit thou on my right hand until I make thine enemies thy footstool.”198

Original Notes Recorded from a Sermon Delivered on 17 May 1843 in William Clayton’s Diary:199At 10 Prest. J. preached on 2nd Peter Ch 1. He shewed that knowledge is power & the man who has the most knowledge has the greatest power. Also that salvation means a mans being placed beyond the power of all his enemies. He said the more sure word of prophecy200 meant a mans knowing that he is sealed up unto eternal life by revelation & the spirit of prophecy through the power of the Holy priesthood. He also showed that it is impossible for a man to be saved in ignorance.201

In the King Follett discourse delivered on 7 April 1844, Joseph Smith explained that God’s purpose in instituting laws for mankind was “to instruct the weaker intelligences,” allowing fallen humanity to gradually “advance in knowledge” so that eventually they “may be exalted with [God] himself.”202 “A knowledge of the priesthood alone” is sufficient for “a man to be saved from all his enemies,” including a “triumph over death.”

In his discourse on 2 Peter 1 given on 14 May 1843, the Prophet taught similarly that the “principle of knowledge is the principle of [Page 72]salvation,”203 therefore “anyone that cannot get knowledge to be saved will be damned.”204 However, when Joseph Smith taught that it is “impossible for a man to be saved in ignorance,” he was not thinking of ignorance in general. He made it clear that only by having one’s calling and election made sure, i.e., being “sealed up unto eternal life by revelation & the spirit of prophecy through the power of the Holy priesthood,” could one receive “the key of the mysteries of the kingdom, even the key of the knowledge of God.”205 He saw within this principle the meaning of the Savior’s own words: “And this is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent.”206 Emphasizing that this “principle can [only] be comprehended by the faithful and diligent,”207 he concluded the thought by reiterating that “The principle of salvation is given us through the knowledge of Jesus Christ.”208

Ascendancy of Those Who Have Received Bodies Over Those Who Have Not

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: organization of spirits in the eternal world. — spirits in the eternal wo[r]ld are like spir[i]ts in this world. when those spirits have come into this [p. [215]] visi[o]n & received grolifed [glorified] bodies. they will have an ascndeny [ascendancy] over spir[i]ts who have no bodi[e]s. or kept not their fi[r]st state [estate] like the devil.209 Devils puni[s]hment. Should not have a habitati[o]n. like othr men — D[e]vils retaliation — come into this w[o]rld bind up mens bod[i]es. & occuppy himself. — authorities come along and eject him from a stolen habitation.

design of the great God. in sending us into this world. and organize[n]g us to prepare us for the Eternal world. —

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: The spirits in the eternal world are like the spirits in this world.210 When those have come into this world and received tabernacles, then died and again have risen and received glorified bodies, they will have an ascendancy over the spirits who have received no bodies, or kept not their first estate,211 like the devil. The punishment of the devil was that he should not have a habitation like men.212 The devil’s retaliation is, he comes into this world, binds up men’s bodies, and occupies [Page 73]them himself.213 When the authorities come along, they eject him from a stolen habitation.214

The design of the great God in sending us into this world, and organizing us to prepare us for the eternal worlds,

Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:215 The design of God before the foundation of the world was that we should take tabernacles that through faithfulness we should overcome & thereby obtain a resrection from the dead,216 in this wise obtain glory honor power and dominion217 for this thing is needful, inasmuch as the Spirits in the Eternal world, glory in bringing other Spirits in Subjection unto them, Striving continually for the mastery,218 He who rules in the heavens when he has a certain work to do calls the Spirits before him to organize them. they present themselves and offer their Services —219

When Lucifer was hurled from Heaven the decree was that he Should not obtain a tabernacle not those that were with him, but go abroad upon the earth220 exposed to the anger of the elements naked & bare,221 but oftimes he lays hold upon men binds up their Spirits enters their habitations222 laughs at the decree of God and rejoices in that he hath a house to dwell in, by & by he is expelled by Authority223 and goes abroad mourning naked upon the earth like a man without a house exposed to the tempest & the storm —

Joseph Smith taught that God has a glorified resurrected body, and that man was created in His literal image and likeness. Despite its imperfect and provisional nature, the human body is a divine gift, provided to enable an essential next step in eternal progression so that individuals might “obtain a resurrection from the dead, [and] in this wise obtain glory, honor, power, and dominion.”224 Elsewhere, the Prophet said: “We came to this earth that we might have a body and present it pure before God in the Celestial Kingdom. The great principle of happiness consists in having a body. The Devil has no body, and herein is his punishment.”225

In LDS discussions of the purpose of the body in mortality today, the necessity of being able “to experience the pleasures and pains of being alive” and to seek “perfection and discipline of the spirit along with training and health of the body”226 are the kinds of reasons most often mentioned. However, as important as these reasons are, the teachings of [Page 74]Joseph Smith almost always highlight the fact that the clothing of spirits with bodies would provide protection for them against the power of Satan. As Matthew Brown succinctly summarizes:227

“All beings who have bodies have power over those who have not,” said the Prophet Joseph Smith.228 The “spirits of the eternal world” are as diverse from each other in their dispositions as mortals are on the earth. Some of them are aspiring, ambitious, and even desire to bring other spirits into subjection to them. “As man is liable to [have] enemies [in the spirit world] as well as [on the earth] it is necessary for him to be placed beyond their power in order to be saved. This is done by our taking bodies ([having kept] our first estate) and having the power of the resurrection pass upon us whereby we are enabled to gain the ascendancy over the disembodied spirits.”229 It might be said, therefore, that “the express purpose of God in giving [His spirit children] a tabernacle was to arm [them] against the power of darkness.”230

Joseph Smith taught that the acquisition of a body in mortality was to enable not only the new experiences of pleasure, pain, and parenthood, but also to provide a protective power from the influences of Satan in both the mortal and the eternal worlds.231

“Some Things in My Own Bosom … Must Remain There”

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: I shall keep in my own bosom.

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: I shall keep in my own bosom at present. … Paul ascended into the third heavens,232 and he could understand the three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder233 — the telestial, the terrestrial, and the celestial glories or kingdoms,234 where Paul saw and heard things which were not lawful for him to utter.235 I could explain a hundred fold more236 than I ever have of the glories of the kingdoms manifested to me in the vision,237 were I permitted, and were the people prepared to receive them.238 [Note that I have inserted the church historians’ expansion regarding Paul’s ascent, previously discussed above in the “ladder and rainbow” section, into what appears to be its proper place so that the three accounts of this section of the sermon can be compared more easily.]

[Page 75]Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:239 There are some things in my own bosom that must remain there. If Paul could say I Knew a man who ascended to the third heaven & saw things unlawful for man to utter, I more.

Because the more complete account in the Coray Notebook was not available to church historians at the time they prepared Joseph Smith’s published history, they mistakenly conjoined in a single sentence (“The design of the great God in sending us into this world, and organizing us to prepare us for the eternal worlds, I shall keep in my own bosom at present”) what were originally two separate thoughts (i.e., “design of the great God …” and “I shall keep in my own bosom”). The “things in my own bosom that must remain there” turn out to be, in the Coray Notebook version, heavenly “things unlawful for a man to utter,” that he saw in vision, not the basic “design of the great God” itself, which he goes on to describe, at least in general terms.

The “design of the great God” or the “the design of God before the foundation of the world,” as it is described in the Coray Notebook, turns out to be connected with the need to provide physical bodies for His children and to help them overcome sin and death so that they may be raised to a glorious resurrection. A few months later, the Prophet made this connection even more explicit: “What was the design of the Almighty in making man, it was to exalt him to be as God.”240

Inextricably linked to the plan for men and women to be exalted together as gods is the doctrine of eternal (and plural) marriage.241 An examination of the historical context at the time this discourse was given makes it clear both why the Prophet felt compelled to address the subject and also why it was discussed only indirectly, by allusion. Andrew F. Ehat describes the background of the precarious situation with regard to the subject that prevailed on 21 May 1843:242

In the aftermath of [John C.] Bennett’s expulsion [from the Church for licentious teachings and practices relating to a counterfeit form of “spiritual wifery”], the crusade in Nauvoo to rid the last vestiges of Bennett’s profligacy … divided the nine-member [“Quorum of the Anointed”243 which consisted of a small group of men who had received their temple endowments on 4 May 1842]. By July 1842, while the other members of the Quorum had accepted eternal and plural marriage, Hyrum Smith, William Law and William Marks had resisted Joseph Smith’s effort to broach the subject with them. Their crusade against the embarrassing activities of [Page 76]Bennett narrowed their perspective, and Joseph Smith soon learned that he should not try then to convert them. This helps explain why in the year after Joseph Smith first gave these endowment blessings to the Quorum he did not invite others to become members of the group, did not yet invite the wives of these men to receive these ordinances, and did not administer any of the more advanced ordinances. …

In May 1843, when Hyrum, William Law and William Marks realized that their efforts had not ended the rumors of the private practice of to them aberrant marriage forms, they decided to bring the issue into the open. They were suspicious that their worst fears were true — Joseph was teaching plural marriage. So while Joseph was out of town, Hyrum spoke on 14 May to the Nauvoo populace taking as his text Jacob 2 in the Book of Mormon — quoting the verses that are a severe denunciation of polygamy.244 … Hyrum said to the Saints, “If an angel from heaven should come and preach such doctrine, [you] would be sure to see his cloven foot and cloud of blackness over his head.”245 The following Sunday, Joseph, in an apparent mild rebuttal, referred to the doctrine of eternal marriage for the first time in public[, as quoted from the notes of his 21 May 1843 sermon given above]. …

Apparently, Hyrum Smith, William Law and William Marks were disturbed by the Prophet’s remarks. They did not understand why some concepts of the Gospel still needed to remain unsaid, concepts relating to the doctrine of eternal covenants. Two days later, Heber C. Kimball and William Clayton “conversed … concerning [rumors they had apparently heard, rumors of] a plot … being laid to entrap the brethren of the secret priesthood [i.e., those who had entered plural marriages246] by bro. H[yrum] and others.”247 …

With this insight into a time of personal dilemma of the Prophet, a point emerges that must be emphasized: Joseph Smith’s actions towards his brother confirm the depth of his religious convictions regarding these principles. The eyes of his people, his closest leaders and associates, and even his brother Hyrum were scrutinizing his every action, and yet he never once faltered. Even the most gracious of humanistic explanations of the origins of plural marriage — the belief [Page 77]and characterization that Joseph Smith’s practice of plural marriage was such a complexly conceived system, so subtly and subconsciously constructed from latent biblical precedent that it totally quieted his own conscience regarding it — seems too superficial a theory to approach describing the fact and reality of Joseph and Hyrum’s experience. He must truly have believed he heard the voice of God to go through what he did from his brother, his counselors in the First Presidency, and from his wife. To carry on such a principle sub rosa for two years without any of the First Presidency the least bit agreeable to the concept is incredible, and yet true.

The Prophet’s actions at this time248 — and subsequently249 — demonstrated that he was more willing to forfeit his life than to deny the truthfulness of what had been revealed to him. Later, Brigham Young remembered that Joseph Smith told him and “scores” of others on many occasions that “if ever there was a truth revealed from heaven through him, it was revealed when that revelation [i.e., on celestial and plural marriage] was given, and if I have to die for any revelation God has given through me I would as readily die for this one as any other. And I sometimes think that I shall have to die for it. It may be that I shall have to forfeit my life to it and if this has to be so, Amen.”250

Our Actions and Contracts Must Be Done with a View to Eternity

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: we have no claim in our eternal compact. in relation to Eternal thi[n]gs [p. [216]] unless our actions. & contracts & all thi[n]gs tend to this end. —

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: We have no claim in our eternal compact, in relation to eternal things, unless our actions and contracts and all things tend to this end.

Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:251 There are only certain things that can be done by the Spirits and that which is done by us that is not done with a view to eternity is not binding in eternity.

Original Notes in Franklin D. Richards “Scriptural Items”:252 Our covenants here are of no force one with another except made in view of eternity.

[Page 78]According to Andrew Ehat and Lyndon Cook, these statements make “allusion to the concept of the eternality of the marriage covenant.”253 The principle expressed here is similar to one that would be written down seven weeks later as part of D&C 132:13:

And everything that is in the world, whether it be ordained of men, by thrones, or principalities, or powers, or things of name, whatsoever they may be, that are not by me or by my word, saith the Lord, shall be thrown down, and shall not remain after men are dead, neither in nor after the resurrection, saith the Lord your God.

Against all expectations, the difficulties the Prophet had faced in the opposition of Hyrum254 and Emma to plural marriage suddenly evaporated during the month of May 1843.255 As Ehat summarizes:256

In some respects May of 1843 must have been an incredibly happy month for the Prophet. If he was delighted with the unexpected conversion of his brother Hyrum to eternal and plural marriage, it could only have been the fitting cap of events of similar surprise that occurred a few days before [on 11 May when “Emma personally participated in Joseph’s marriage to four plural brides, Eliza and Emily Partridge and Sarah and Maria Lawrence, all with her explicit approval”257].

On 26 May 1843, five days after the 21 May sermon and apparently due at least in part to the conversion of Hyrum258 and Emma to the principle, the Quorum of the Anointed met for instruction for the first time in a year.259 At this meeting, “the first ordinances of endowment” were administered.260 Two days later, Joseph and Emma were the first couple in the Quorum to be married for time and eternity; others received the same ordinance soon afterward.261 Though Emma continued to struggle with the principle of plural marriage,262 she and Joseph together received the “highest and holiest order of the priesthood,” the “fulness of the priesthood,”263 or “second anointing”264 on 28 September 1843.265 Later, Emma “oversaw and administered temple ordinances to female Church members.”266 As the Prophet had taught on other occasions, receiving the fulness of the priesthood is a prerequisite to having one’s calling and election made sure.267

[Page 79]

Summary of the Three Keys Hidden in 2 Peter 1

Original Notes from Joseph Smith’s Journal: after all this make your calling and election sure. if this injuncti[o]n would lay lageley [largely] on those to whom it was spoken. how much more those to who th[e]m of the 19. century. —

<1 Key> Knowledge in [is] the power of Salvati[o]n

<2 Key> Make his calling and Election Sure

3d — it is one thing to be on the mount & hear the excellent voice &c &c. and another <to hear the> voice de[c]lare to you you have a part & lot in the kingdom. — [4 lines blank] [p. [217]]

Expanded Version from Joseph Smith’s History: But after all this, you have got to make your calling and election sure. If this injunction would lie largely on those to whom it was spoken, how much more those of the present generation!

1st key: Knowledge is the power of salvation. 2nd key: Make your calling and election sure. 3rd key: It is one thing to be on the mount and hear the excellent voice, &c., &c., and another to hear the voice declare to you, You have a part and lot in that kingdom.

Original Notes in the Martha Jane Knowlton Coray Notebook:268 Oh Peter if they who were of like precious faith with thee were injoined to make their Calling & Election sure, how much more all we There are two Keys, one key knowledge. the other make you Calling & election sure, for if you do these things you shall never fall for so an entrance shall be administered unto you abundently into the everlasting Kingdom of our Lord & Savior Jesus Christ. We made known unto you the power & coming of our Lord & S. J. Christ were Eye witnesses of his Majesty when he received from God the Father honor & glory when there came such a voice to him from the excellent glory, this is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased. this voice which came from heaven we heard when we were with him in the holy Mount. We have also a more sure word of prophecy whereunto give heed until the day Star arise in your hearts this is It is one thing to receive knowledge by the voice of God, (this is my beloved Son &c.) & another to Know [Page 80]that you yourself will be saved, to have a positive promise of your own Salvation is making your Calling and Election sure. viz the voice of Jesus saying my beloved thou shalt have eternal life. Brethren never cease strugling until you get this evidence. & Take heed both before and after obtaining the more sure word of Prophecy.

Joseph Smith concluded by answering the question he raised at the beginning of the sermon: What could be “more sure” than hearing the voice of God bearing testimony of His Son? After summarizing the three linked keys that are hidden in the first chapter of 2 Peter, he urgently enjoined the Saints to do everything necessary to make their calling and election sure so they would be eligible to receive the divine knowledge that constitutes the ultimate power of salvation. This knowledge does not come merely by hearing the voice of God speak, as when Peter heard the Father’s testimony of the Son, but through the “more sure” promise of eternal life made with the Father’s personal oath to Peter afterward.

Though non-LDS commentators understandably fail to grasp the full nature and import of Peter’s experience on the Mount of Transfiguration, some at least clearly sense the implication of his subsequent words269 for every reader of the epistle. According to the editors of the esv “believers are admonished to ‘pay attention’ to the certainty of the ‘prophetic word.’ In the contrast between ‘we have’ and ‘you will do well,’ Peter is apparently emphasizing that the interpretation of the apostles (‘we’) is to be regarded as authoritative for the church (‘you’)”270 — while striving themselves, meantime, to obtain the same “prophetic word” that Peter possessed (i.e., “take heed [unto our more sure word], as unto a light that shineth in a dark place, until the day dawn, and the day star arise in your hearts).”271 Not only Jesus and Peter, but every one who endures to the end in keeping “all the commandments” and obeying “all the ordinances of the house of the Lord,”272 can look forward with eager anticipation to the day when they will hear the Father’s declaration that they have become, at last, as His beloved Son, in whom He is well pleased.

Conclusions

Having spent much of my life in focused study of translations, revelations, and teachings of Joseph Smith, I have been astonished with the extent to which they reverberate with the echoes of antiquity — and, no less significantly, with the deepest truths of my personal experience. Indeed, I would not merely assert that the words of Joseph Smith hold up well under close examination, but rather that, like a fractal whose self-similar [Page 81]patterns become more wondrous upon ever closer inspection, the brilliance of their inspiration shines most impressively under bright light and high magnification: there is glory in the details. My hope is that this glory will be more fully revealed and appreciated as we take advantage of our unparalleled access to the words of the Prophet in order to more fully understand and apply them personally.

Acknowledgments

My deep appreciation to Matthew Bowen, Don Bradley, David Calabro, Andrew F. Ehat, Paul Hoskisson, David Larsen, Ben McGuire, Eric D. Rackley, John S. Thompson, John W. Welch, Stephen T. Whitlock, and anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and feedback. I am also grateful to Julie Griffin, Tim Guymon, Tanya Spackman, and Allen Wyatt for their help in editing and preparing the article for publication.

References

Alleman, John C. “Problems in translating the language of Joseph Smith.” In Conference on the Language of the Mormons (May 31, 1973), edited by Harold S. Madsen and John L. Sorenson, 22–31. Provo, UT: Language Research Center, Brigham Young University, 1973.

Allen, James B. No Toil Nor Labor Fear: The Story of William Clayton. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91–221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Ballard, M. Russell. 2016. The opportunities and responsibilities of CES teachers in the 21st century (Address to CES Religious Educators, CES Evening with a General Authority, 26 February 2016, Salt Lake Tabernacle). In LDS Broadcasts. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/broadcasts/article/evening-with-a-general-authority/2016/02/the-opportunities-and-responsibilities-of-ces-teachers-in-the-21st-century?lang=eng. (accessed March 19, 2016).

Barker, Margaret. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. On Earth as It Is in Heaven: Temple Symbolism in the New Testament. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1995.