Abstract: This study compares personal relative pronoun usage in the earliest text of the Book of Mormon with 11 specimens of Joseph Smith’s early writings, 25 pseudo-archaic texts, the King James Bible, and more than 200,000 early modern (1473–1700) and late modern (1701–1800+) texts. The linguistic pattern of the Book of Mormon in this domain — a pattern difficult to consciously manipulate in a sustained manner — uniquely points to a less-common early modern pattern. Because there is no matching of the Book of Mormon’s pattern except with a small percentage of early modern texts, the indications are that Joseph Smith was neither the author nor the English-language translator of this pervasive element of the dictation language of the Book of Mormon. Cross-verification by means of large database comparisons and matching with one of the finest pseudo-archaic texts confirm these findings.

“All they which fight against Zion shall be cut off ” (1 Nephi 22:19)1

Syntactostylistics is the study of the stylistic implications of syntactic variation. One of the most important areas of syntactostylistics in relation to the Book of Mormon, with clear authorship implications, is the systematic use of relative pronouns in the original text, in particular when these pronouns refer to persons. This kind of syntax is one of the most important pieces of evidence that the Book of Mormon is formulated with nonbiblical, archaic syntax. At this point, I have completed quite a few other studies of a similar nature that indicate or suggest the same. It is my aim to publish some of these studies in the near future. Among them, the Book of Mormon’s verb complementation pattern, though archaic, stands out clearly as nonbiblical and non-pseudo-archaic. [Page 6]I currently know of no external textual evidence that might suggest that Joseph Smith would have formulated the Book of Mormon’s clausal complementation patterns in the way we find them in the text (more than 500 instances: sustained, heavy finite usage).2 The frequent use of the modal auxiliary shall as a subjunctive marker in certain contexts, such as in clauses governed by verbs of influence, is another archaic syntactic marker that makes the text stand out from pseudo-archaic texts.3 The Book of Mormon’s pervasive periphrastic did usage is another one.4 The text’s partly nonbiblical and often non-pseudo-archaic subordinate that usage is another one.5 And so forth.

The Book of Mormon’s personal relative pronoun usage has been less thoroughly covered in an earlier article and in the text-critical volume The Nature of the Original Language (NOL).6 For that NOL study, large database comparisons had not been as fully carried out, nor had the view been expanded to 25 pseudo-archaic texts or to Joseph Smith’s earlier epistolary writings (see the appendix for how these pseudo-archaic texts were chosen). Now I have finished making WordCruncher7 databases — both large and small — of these texts and writings. In the case of the larger textual record of English, I am now able to closely compare Book of Mormon usage with about 10 billion words first published between the years 1473 and 1829 (the early modern corpus, EEBO,8 has texts dated between 1473 [the first printed book in English] and 1700; the late modern corpus, ECCO,9 has texts dated primarily between 1701 and 1800, with a relatively small number of texts first published after the year 1800).

Before considering the textual evidence, it is important to clarify the version of the Book of Mormon that must be analyzed. The dictation language must be our object of inquiry, and not the 1837 edition or the 1840 edition, so as to avoid biasing the outcome. If Joseph Smith was the author or English-language translator10 of the Book of Mormon, then that will reveal itself in the dictation language. If he was not the author or English-language translator, then that might or might not reveal itself in a later lifetime edition, depending on what syntax and lexis is being studied, since the second and third editions contain readings that were greatly altered by conscious editing. In no other linguistic domain is that more applicable than in the text’s personal relative pronoun usage, since so many of these were changed for the second edition.11 Because of this, we must study the earliest text to avoid possibly predetermining the outcome of this linguistic study as well as others.

[Page 7]Another important point to bear in mind is that we look to pseudo-archaic texts to see what linguistic elements their authors were able to control and alter, elements that are usually a matter of nonconscious production, such as relative pronoun usage. In composing their texts, pseudo-archaic authors attempted to alter various formal and structural features of their native language. They were able to alter linguistic usage to an extent, and morphosyntactic features such as verb agreement and verb endings were more readily imitated than other kinds of syntax. Nevertheless, they were able to go beyond mere morphosyntactic alteration, modifying other syntactic and lexical features. We may grant to Joseph Smith, as a presumed author or translator from revealed ideas, the ability to be among the finest pseudo-archaic stylists, such as Richard Grant White, the Shakespearean scholar. The working assumption, then, is that Joseph Smith, though dictating a text with complex content, might have focused on meaning-neutral personal relative pronoun usage. But I do not assume that he was able to produce what no pseudo-archaic author produced in this domain. To go beyond that level is to enter a gray area of possible supernatural control of vocabulary, forms, and structures.

With that in mind, I compared what Joseph Smith produced in this domain with what pseudo-archaic authors produced. An examination of these texts indicates that as far as personal relative pronoun usage is concerned, Joseph Smith was unlikely to have sustained conscious manipulation of usage patterns that varied substantially from modern usage beyond some slight biblical influence. Most pseudo-archaic authors show a modern pattern, heavy in who or whom. A few produced more personal that than was normal for their time, showing that they were able to imitate biblical usage a little more closely, but no one came very close to being biblical in this regard. Most telling is that no pseudo-archaic author produced usage that was heavy in personal which, such as representing more than half the relative personal pronoun usage, as we find in the Book of Mormon. Thus, even if Joseph Smith had been able to closely imitate biblical patterns in this domain, he almost certainly would not have produced the heavy personal which of the Book of Mormon.

A reasonable conclusion is that the original dictation language does not present as a pseudo-archaic text in this syntactic domain. This is a pattern that is a pervasive, integral part of the language and not merely found in scattered portions of the text (there are more than 1,600 instances in mostly nonbiblical sections).

[Page 8]Personal Relative Pronouns and Variation

As an introduction to personal relative pronouns, consider these two pairs of simple English expressions:

- A friend that was at the party told me.

- A friend who was at the party told me.

- Someone who was here last night left those keys.

- Someone that was here last night left those keys.

The words highlighted above have to do with the variable syntax of relative pronoun selection. In the above examples, there is a choice to be made among that and who after the noun friend and the indefinite pronoun someone. As shown, there is variation in the relative pronoun used. Both that and who are acceptable to most native English speakers. When we say things like this, we do not think about which relative pronoun we use, and we probably do not even have a sense of how often we use one or the other, and after what words and in what contexts we use one more than the other. Personal relative pronoun (PRP) usage patterns are shaped by our linguistic environment — what sounds right to us depends heavily on what we have heard and read growing up.

In earlier English, there was yet another PRP option commonly available to speakers and writers: personal which. This is the option we see most often in the original Book of Mormon text. We can replace that or who above with which to get a sense of how this option sounds/reads:

- A friend which was at the party told me.

- Someone which was here last night left those keys.

Even today, we occasionally encounter the use of personal which in prepositional phrases — in phrases such as “many of which” or “some of which” — but besides that, we either do not encounter it or hardly ever encounter it.12

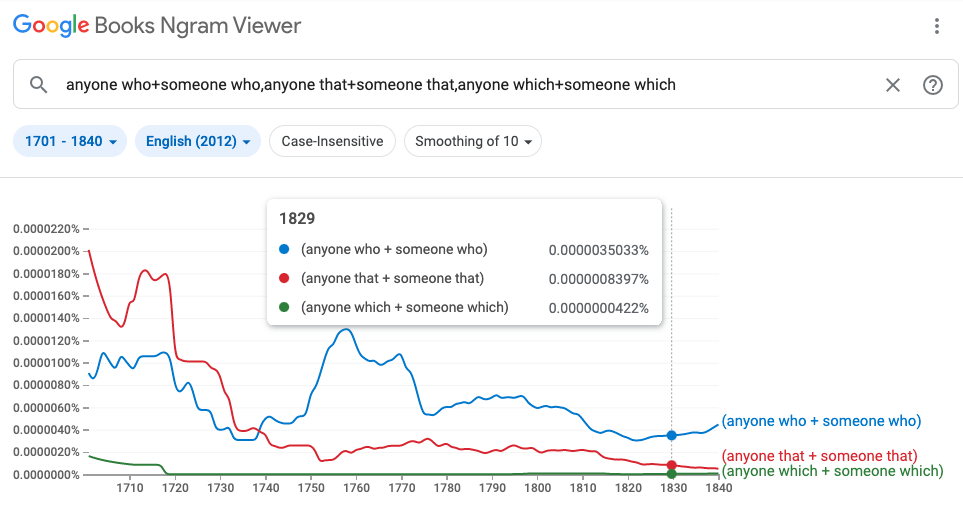

We can see in the textual record that English underwent broad pattern shifts over time. Usage of personal which (as a relative pronoun) had become rare for most English speakers well before the 19th century. By the early 1800s, the decades when Joseph Smith was absorbing information from his linguistic environment, a bare minimum of personal which usage was the norm for most English speakers and in most dialects, including in Joseph’s own American English dialect. This can be seen in Google’s Ngram Viewer,13 where we can compare usage rates of “anyone/someone who/that/which.”

[Page 9]

Figure 1. Late modern personal relative pronoun rates after indefinite pronouns.14

Figure 1 indicates that anyone who and someone who were dominant in the 1820s over anyone that and someone that; and anyone which and someone which are two orders of magnitude below the who variants. In the early 1700s, “anyone/someone that” was still dominant, but by the late 1700s “anyone/someone who” was dominant. Though it would not be unusual to find scattered instances of personal which in Joseph’s day, including in his own early writings (there are two of them), the use of personal which was dwarfed by competing options.

It is important to keep in mind that PRP selection can vary considerably, even for a single author. It would be unusual for an earlier English author or translator, in a lengthy text, to use just one of the three PRP options all of the time. This can be seen in many writings of the past, including the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon. Here are four examples of PRP variation after the demonstrative personal pronoun those:

| Ezra 8:35 | Also the children of those that had been carried away which were come out of the captivity, |

| Mosiah 15:21 | yea, even a resurrection of those that have been and which are and which shall be, |

| 1574, EEBO A69056 | So then what shall become of those that have nothing but infirmity, and which have scarcely received three drops of courageousness to sustain themselves withal in the mids[t] of their afflictions? |

| 1690, EEBO A30434 | we must likewise believe that he loves those that are truly good, and are conformable to [Page 10]his own nature, and that he has an aversion to those who are contrary to it, and that are defiled and impure: |

In these excerpts, we see those that varying closely with “those … which.” The last excerpt has those that, then those who, followed by “those … that.” These are examples of nearby PRP variation, which was and still is part of natural language use.

This study compares the PRP usage found in the Book of Mormon and the following:

- Joseph Smith’s early writings (10 letters and his 1832 personal history)15

- 25 pseudo-archaic writings (see the appendix)

- the King James Bible

- tens of thousands of early modern and (late) modern texts

(EEBO [1473–1700] and ECCO [1701–1800+])

If Joseph was the author or translator of the text, then we reasonably expect a number of syntactic structures in the Book of Mormon to roughly match any of three things: King James–style, which he was presumably imitating; the usage of various pseudo-archaic authors, who were trying to mimic biblical and/or archaic usage; or his own way of expressing things. Examining how these sources employed PRPs reveals that Book of Mormon usage is unexpected and out of the ordinary.

The approach taken for this study was to compare complete datasets with each other and syntactically sampled sets with each other. In particular, all instances found in the Book of Mormon have been compared against all instances found in Joseph Smith’s early writings. Also, syntactically and semantically sampled instances from the Book of Mormon have been compared to syntactically and semantically sampled instances taken from the first three items listed above. Finally, a more limited type of PRP usage was compared between all the texts and corpora, as discussed below.16

A Complete Comparison of PRP Patterns

In comparing the PRP usage of Joseph Smith’s early writings and the Book of Mormon, all potential instances were noted, except those occurring in sections heavy in biblical quoting. Nonbiblical language was targeted, as it is hypothetically more likely to represent Joseph’s own usage, without external linguistic influence or contamination. Both texts have easily identifiable biblical quotations as well as instances of biblical [Page 11]blending. I did not include the PRP usage found in the most obvious biblical quotations, but it was included in borderline cases involving biblical blending.

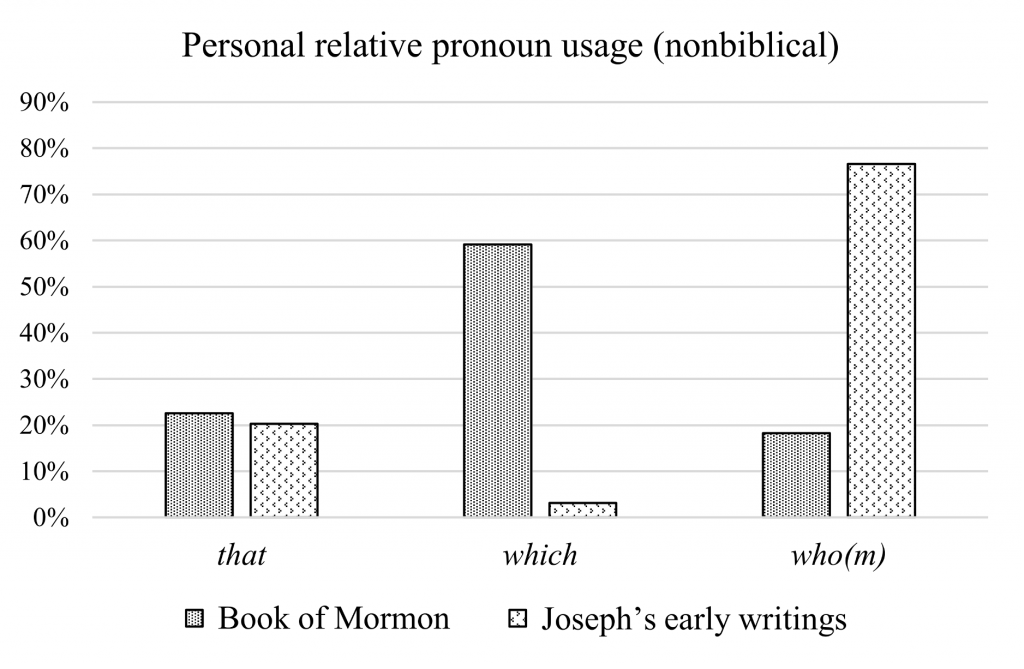

With these exclusions, the distribution of PRP selection in the Book of Mormon and Joseph’s early writings is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. PRP instances and rates in the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith’s early writings (nonbiblical sections).17

| that | which | who(m) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Book of Mormon, nonbiblical | 370 | 939 | 300 | 1,609 |

| Early writings, nonbiblical | 13 | 2 | 49 | 64 |

| Χ² ≈ 132.6, p ≈ 2×10–29; p ≈ 6×10–10 (n = 50) | ||||

| Book of Mormon, nonbiblical | 23.0% | 58.4% | 18.6% | |

| Early writings, nonbiblical | 20.3% | 3.1% | 76.6% | |

Because chi-square tests can be very sensitive to large n’s — as occur in the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon in this case — I ran chi-square tests for all the texts using not only the raw numbers, but also using n = 50 as a common baseline. In order to achieve n = 50, seven texts had their observed numbers reduced and eight texts had their observed numbers increased (see Table 4 for a complete listing of the raw numbers and the chi-square tests; Table 5 shows the tests run on reduced numbers).

Figure 2. PRP rates in the Book of Mormon and Joseph’s early writings (nonbiblical).

[Page 12]This comparison shows large differences in the case of which and who(m). In the Book of Mormon, which is strongly preferred, with that slightly exceeding who(m). In contrast, Joseph Smith had a strong personal preference for who(m) over that, with which a distant third. Figure 2 graphically shows that Joseph’s native PRP usage pattern was markedly different from that of the Book of Mormon.

The big picture is that the Book of Mormon is more than half personal which, and Joseph Smith’s native preference was more than two-thirds who or whom.

A Comparison of Large Subsets of PRP Instances

Next to check were authors who were trying to emulate biblical/archaic patterns, to find out whether they produced anything like the Book of Mormon’s pattern. For the above comparison, I noted virtually all instances of PRP usage. But in comparing Book of Mormon usage with what is found in 25 pseudo-archaic texts and the King James Bible, I sampled a large portion of PRP usage systematically, noting usage in contexts with higher frequency antecedents18 and without any intervening punctuation (thus reducing false positives as well as focusing on relative clauses mostly restrictive in function).19 Thus the sampling was not randomly determined but was based on syntax and semantics, so the comparisons were more likely to have greater relevance.20

Among the 25 pseudo-archaic texts examined, there was no matching whatsoever with the Book of Mormon’s PRP patterns, whether we consider the 12 longer pseudo-archaic texts or the 13 shorter ones. In the 12 longer texts, none of the authors preferred which over the other two possibilities. Eight of the 12 clearly preferred who(m) to that, with which a distant third. This preference is a modern profile and it matches what we see in Joseph Smith’s personal writings, as shown above. As a result, the chi-square tests between these eight texts and his early writings are not statistically significant — that is, p > 0.05. The pattern of these eight longer pseudo-archaic texts, then, was the most likely one for Joseph to have produced in an effort to produce biblical archaism.

Three of the 12 longer texts reflected, to a slight degree, a biblical preference for personal that. This was the second most likely result for the Book of Mormon, had it been the result of a pseudo-archaic effort. Only one of the 12 split usage among personal that and who(m). Ten of the 12 did not employ any personal which in the targeted contexts, and the two that did employ personal which employed it at far lower rates [Page 13]than occurs in the Book of Mormon, especially Gilbert Hunt, whose personal which usage in The Late War stands at only three percent.21

The only pseudo-archaic author who employed personal which at a non-negligible rate was the Shakespearean scholar Richard Grant White, who wrote his text, The New Gospel of Peace,22 three decades after the Book of Mormon. His greater familiarity with Early Modern English might explain his somewhat elevated personal which usage. Nevertheless, White’s personal which usage rate of 18 percent is still far below the Book of Mormon’s rate in the targeted context, 52 percent.23

White’s pseudo-archaic text is one of the best in terms of producing earlier usage, in several different ways, not just in PRP usage. As an example from this domain, among all pseudo-archaic texts, White’s text is the only one with instances of personal them which (14 of them), as in the following excerpt:

2:6:14 they fell upon them which were already free in Gotham

The King James Bible has more than 100 instances of the string “them which” and the Book of Mormon has 34 in nonbiblical contexts, as in these two examples:

| Judges 14:19 | and gave change of garments unto them which expounded the riddle |

| 3 Nephi 3:14 | — or of all them which were numbered among the Nephites — |

The occurrence of personal “them which” in a text is either a small sign of true archaism, knowledge of earlier archaism, or a great ability to reproduce biblical archaism.

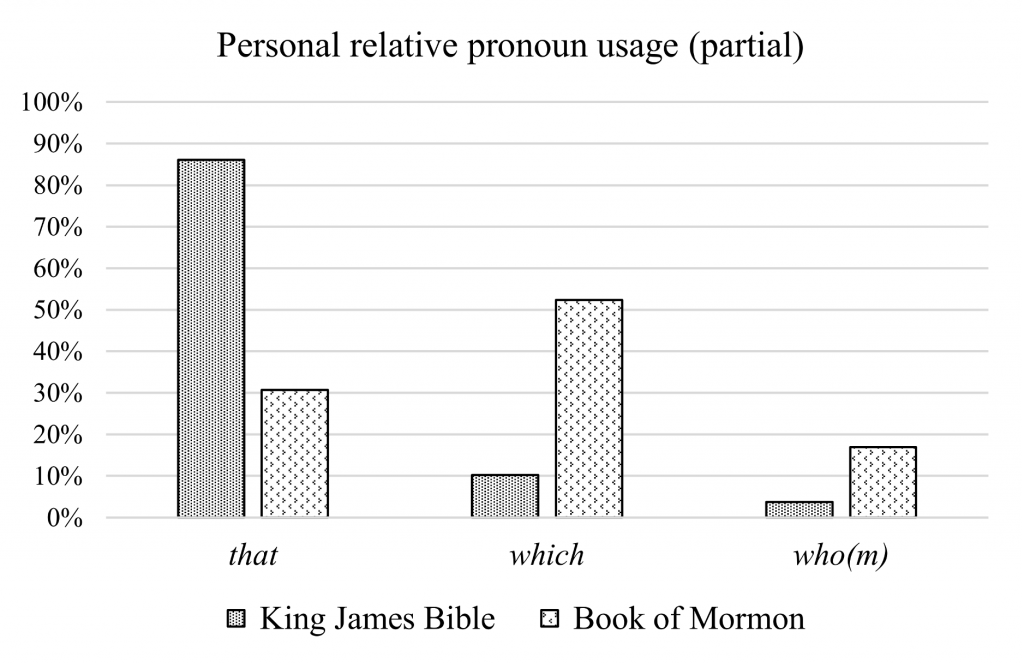

The rates of PRP selection in the King James Bible compared with the Book of Mormon (syntactically and semantically sampled) are as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. PRP rates in the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon with high-frequency antecedents and in restrictive relative clauses (no intervening punctuation).

| that | which | who(m) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| King James Bible | 86% | 10% | 4% | 3,194 |

| Book of Mormon | 31% | 52% | 17% | 837 |

| Χ² ≈ 1067, p ≈ 2×10–232; p ≈ 1×10–7 (n = 50) | ||||

Figure 3 shows how different from each other these usage patterns are. In restrictive relative clauses, the King James Bible is dominant [Page 14]in personal that (more than 75 percent) and the Book of Mormon is dominant in personal which (more than 50 percent). The biblical pattern was the dominant early modern profile, and the Book of Mormon’s pattern was a much less common early modern profile.24

Figure 3. PRP rates in the Bible and Book of Mormon.

A Comparison of PRP Usage After He and They

In order to reliably tally PRP usage in tens of thousands of texts, without individual inspection, we can reduce the number of false positives by limiting the antecedents to subject pronouns, the most frequent being he and they. By limiting searches to the following strings —

he that • he which • he who(m) • they that • they which • they who(m)

— we obtain tallies of textual usage that allow us to determine closeness of fit with the Book of Mormon’s pattern somewhat more easily. The databases I inspected — EEBO and ECCO — yielded 26,101 texts25 with at least 20 instances of “he/they <rel.pron.>” (no intervening punctuation allowed).

Besides facilitating a reliable scan of tens of thousands of texts without generating very many false positives, this is also a way to focus on greater archaism, since a high usage rate of “he/they <rel.pron.>” is more characteristic of earlier modes of expression. In other words, texts with relatively large amounts of “he/they <rel.pron.>” tend to be more [Page 15]archaic.26 Alternatives such as “(any/some) one <rel.pron.>” and “those <rel.pron.>” began to be used more heavily as time went on.

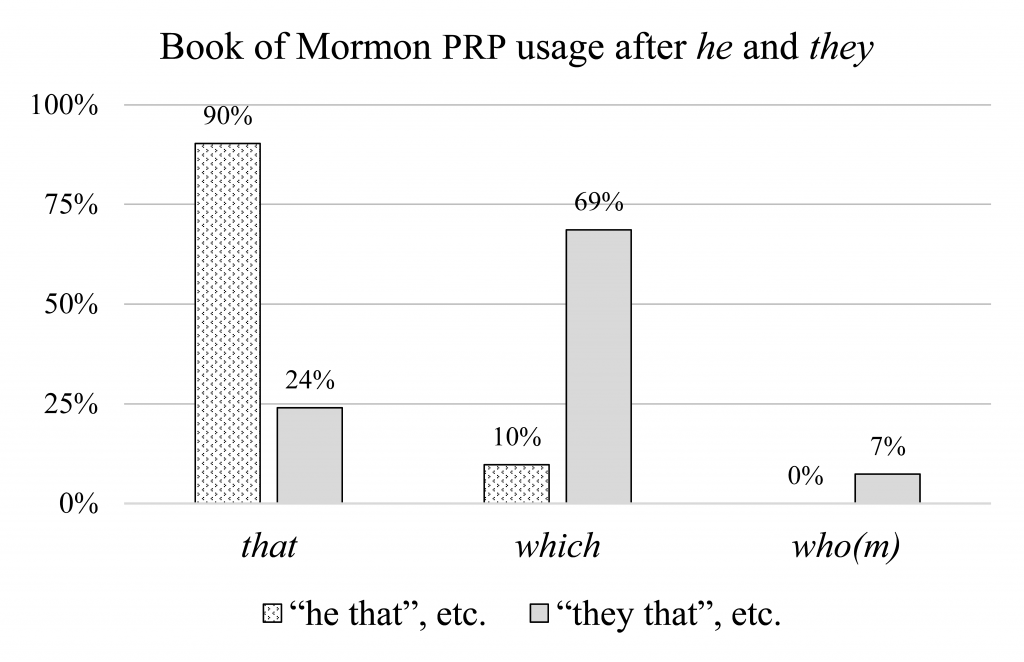

The Book of Mormon has a striking pattern divergence that hinges on whether the antecedent is he or they (n = 228, nonbiblical sections). Personal which is dominant after they; personal that is dominant after he, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Divergence in PRP rates after he and they in the Book of Mormon

[Χ² ≈ 91.5, p ≈ 1×10–20; p ≈ 1×10–10 (n = 50)]

The Book of Mormon’s he and they patterns are noticeably different. As Figure 4 indicates, there was originally no “he who(m)” in the nonbiblical sections of the Book of Mormon (there is one biblical instance at 2 Nephi 24:6: “He who smote the people in wrath”). The text has been edited so that the 1981/2013 edition has eight instances of “he who” in nonbiblical sections.

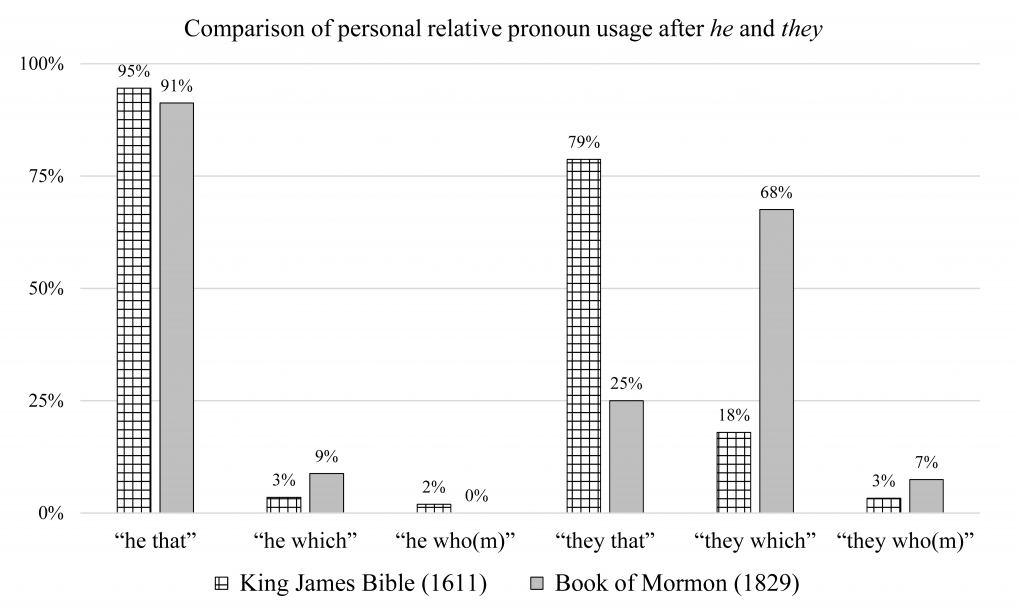

Figure 5 compares “he/they <rel.pron.>” usage in the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon. This chart shows the closeness of the scriptural patterns when the antecedent is he (on the left) and the strong divergence in the case of they (on the right). The chi-square test yields an extremely small p-value (though again, statistical calculations are not needed to demonstrate the obvious differences).

The entire EEBO database was found to have 82 texts (n ≥ 20; a handful of these near duplicates) in which the raw tallies were a close fit with this particular Book of Mormon usage pattern.27 In some of these texts, all instances of “they that/which” are personal; in other texts, some [Page 16]instances are nonpersonal. For example, in the closest matching text — Thomas Cartwright [1535–1603] (attributed name), A second admonition to the parliament (1572), A18079 — all instances of “they that/which” are personal. But in Thomas Elyot’s The Castle of Health (1536), some instances of “they that/which” are nonpersonal, and the closeness of fit with the Book of Mormon is slightly less than the raw result.28

Figure 5. Comparison of “he/they <rel.pron.>” in the Bible and Book of Mormon.

[N(King James Bible) = 1,134; N(Book of Mormon) = 228, nonbiblical sections;

Χ² ≈ 1067, p ≈ 2×10–232; p ≈ 0.0003 (n = 50)]

In the Book of Mormon, the divergence is limited to pronominal antecedents and not necessarily related to number — that is, it is not a general singular/plural divergence, since singular noun phrases do not show a preference for personal that over personal which. Both singular and plural noun phrases, when divided into two groups, show a preference for personal which. However, plural noun phrases do take which to a higher degree than singular noun phrases (approximately 80 percent versus 60 percent).

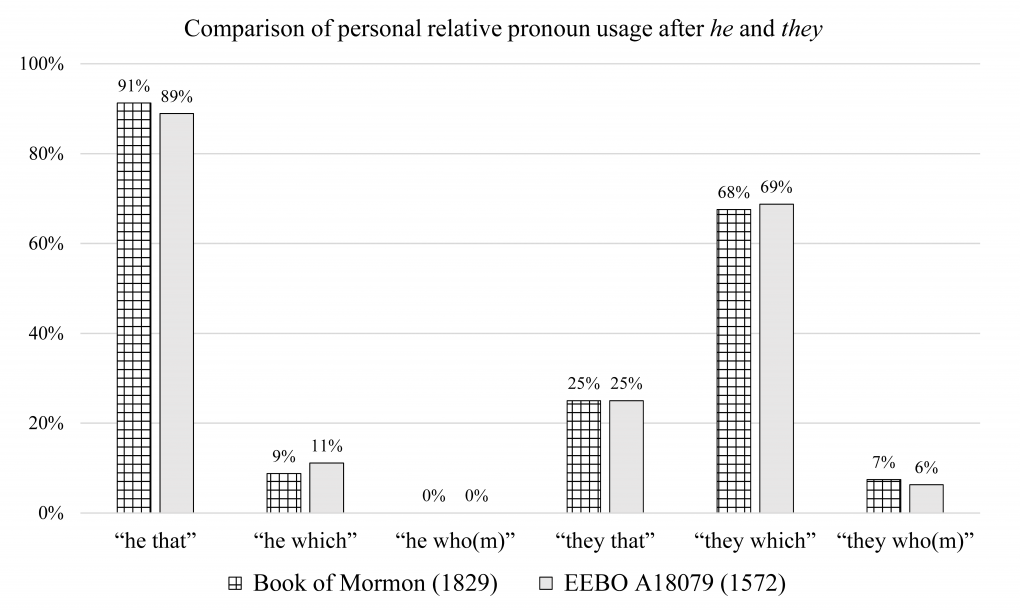

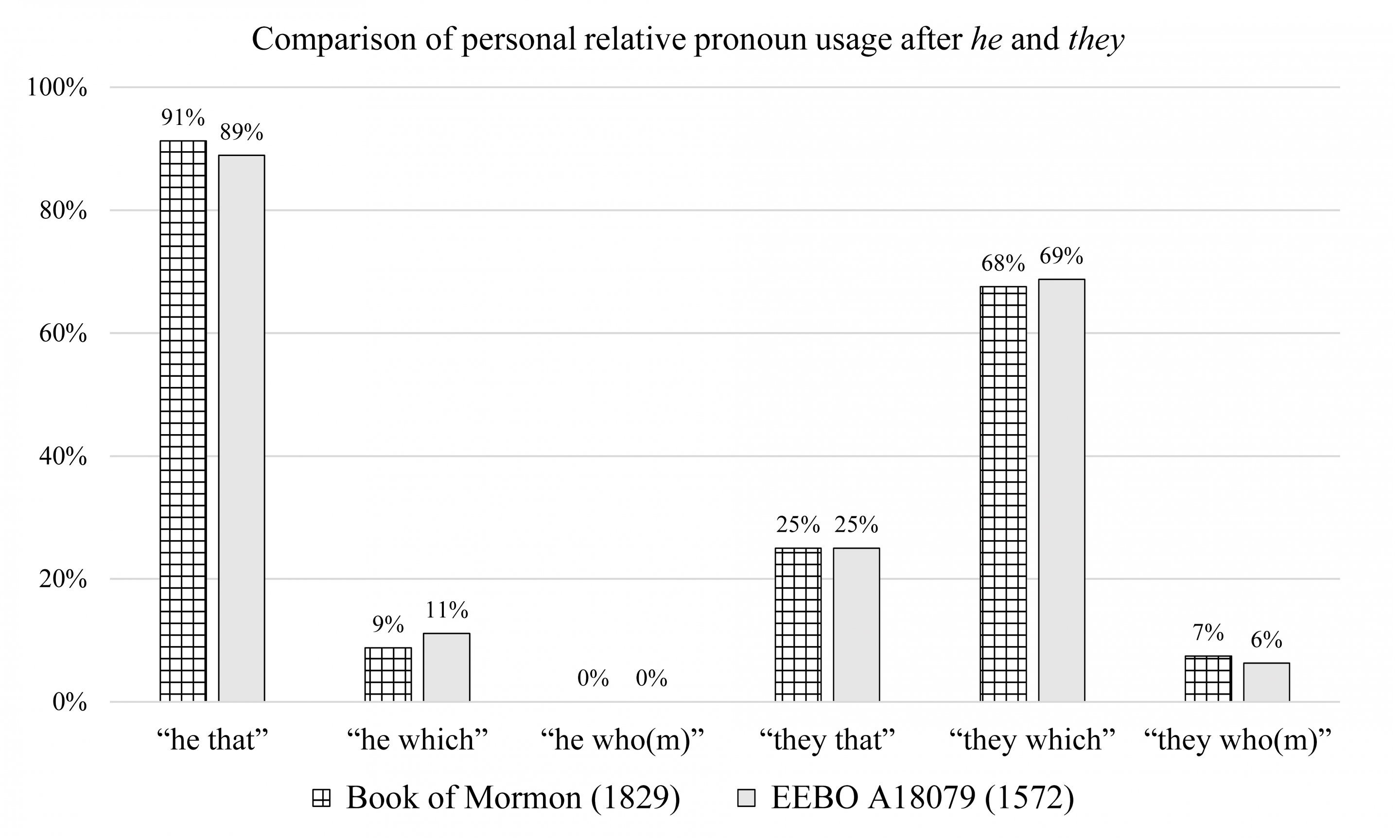

These closely matching EEBO texts provide evidence that this pattern divergence occurred in earlier English. The average matching date is 1604, and the weighted average date, taking into account publication rates increasing over time, is close to 1580. Shown in Figure 6 is the EEBO text whose PRP usage after he and they matches Book of Mormon usage most closely.

[Page 17]

Figure 6. Comparison of “he/they <rel.pron.>” in the Book of Mormon

and a text published in 1572, attributed to Thomas Cartwright.

[N(Book of Mormon) = 228, nonbiblical sections; N(EEBO A18079) = 25;

Χ² ≈ 0.095, p ≈ 0.9999; p ≈ 0.9998 (n = 50)]

. . .

Out of just over 195,000 mostly 18th-century ECCO volumes (many thousands of these near duplicates, and some of these early 19th-century texts), only five distinct texts were found to match the Book of Mormon closely (a sixth text was a near duplicate). All five turned out to be early modern texts. One was by an author born in 1589, Timothy Rogers (1618, CW0122204280 [1784]: A Righteous Man’s Evidence(s) for Heaven).29 Two texts contained extracts from John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, first published in the 1560s (CW0117792407, 1751; CW0117389458, 1761). A fourth ECCO text contained memorials from the time of Queen Elizabeth and King James I (CW0106210422, 1725). A fifth text was a 1575 translation of a Galatians commentary by Martin Luther (CW0119359562, 1774).

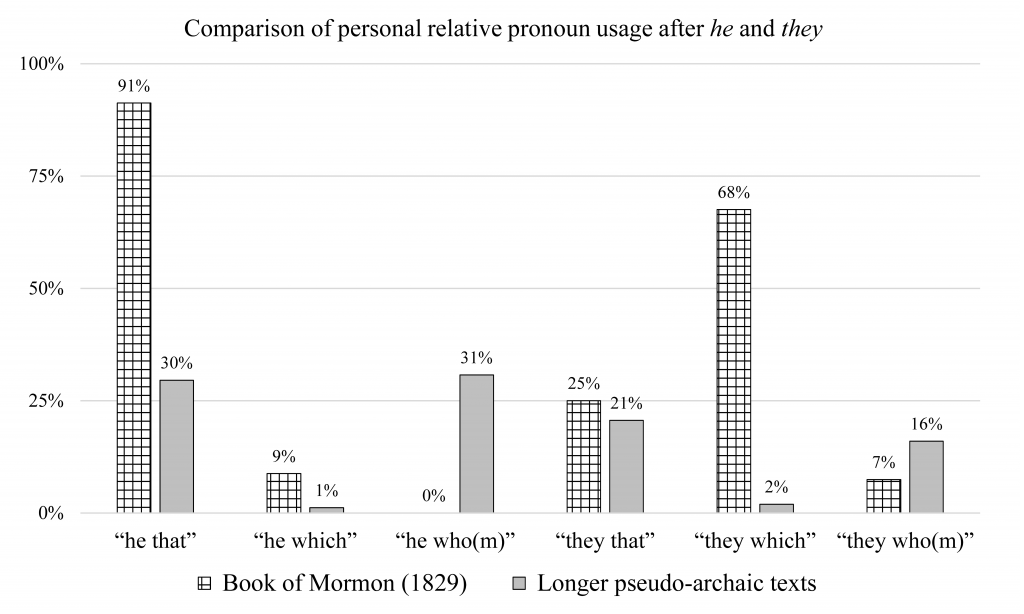

Only the longer pseudo-archaic texts turned out to have instances of “he/they <rel.pron.>” (10 of the 12 longer texts). Of these 10, five had at least 19 instances. Among these five pseudo-archaic texts, there was no close fit with the Book of Mormon’s pattern. The Book of Mormon has 73 instances of “he that” and 100 instances of “they which.” The five pseudo-archaic texts have between 6 and 19 instances of “he that,” but only one text had instances of “they which” (five of them): Richard Grant White’s [Page 18]New Gospel of Peace (1863). Figure 7 compares the Book of Mormon with the sum of the 10 longer pseudo-archaic texts in this domain.

Figure 7. Comparison of “he/they <PRP>” in the Book of Mormon and 10 longer pseudo-archaic texts.

[N(Book of Mormon) = 228; N(pseudo-archaic) = 257; Χ² ≈ 189.8,

p ≈ 4×10–39; p ≈ 3×10–7 (n = 50)]

The distribution profiles are noticeably different, with the most noticeable differences between “he/they who(m)” and “they which” usage.

It is also instructive to make “he/they <rel.pron.>” comparisons of White’s 1863 pseudo-archaic text (n = 63) with texts from the EEBO and the ECCO databases that have at least 20 instances. The Shakespearean scholar White knew much more Early Modern English in his time than Joseph Smith did in the 1820s. While the Book of Mormon closely matches 82 EEBO texts, White’s New Gospel of Peace closely matches only 40 EEBO texts, about half the number. The average year of these closely matching texts is 1665 (the weighted average year is about 1650; publication dates range between 1600 and 1700). The weighted average years of texts that closely match the “he/they <rel.pron.>” patterns of the Book of Mormon and White’s pseudo-archaic text are 70 years apart. Furthermore, if publishing rates of titles had been steady across the decades of the early modern period, then the Book of Mormon would have probably closely matched between five and ten times as many EEBO texts as White’s pseudo-archaic text.

[Page 19]In comparisons of more than 18,000 eighteenth-century texts (ECCO database, n ≥ 20), White’s text closely matches 93 texts, many of these actually 18th-century texts (an unknown number of these are duplicates or from the early modern era).30 As mentioned, the Book of Mormon closely matches only five distinct texts (six total), all early modern. Thus, the Book of Mormon presents as an older and even a genuinely archaic text in this domain, while White’s text, though linguistically speaking a fine pseudo-archaic effort, is a borderline early/late modern case, and much less archaic than Joseph’s dictation language. Table 3 summarizes these results.

Table 3. Close matching with the “he/they <rel.pron.>” profiles of the

Book of Mormon and Richard Grant White’s 1863 pseudo-archaic text.31

| EEBO Texts | ECCO Texts | |

|---|---|---|

| Book of Mormon | 82 (avg. yr: 1580) | 6 (all early modern) |

| New Gospel of Peace | 40 (avg. yr: 1650) | 93 (late & early modern mix) |

Conclusion

The statistical argument for each scenario outlined above is compelling — whether we look at all PRP usage, a subset involving high-frequency antecedents, or just contexts involving the subject pronouns he and they. We can tell with exceptionally high confidence that the Book of Mormon’s PRP patterns were not derived from Joseph Smith’s own patterns, from the King James Bible, or from attempting to imitate biblical and/or archaic style. We can also tell that the patterns do match a less-common pattern that prevailed during the middle portion of the early modern period, but not in the 18th century — a pattern with an overall preference of personal which over that or who(m).

In the case involving more antecedents than just he and they, a simple examination of the dramatic differences shown here or an application of standard chi-square tests of the raw numbers (see the appendix) indicate that the Book of Mormon’s PRP pattern would not have been achieved by closely following the patterns of the King James Bible, pseudo-archaic works, or Joseph’s own dialectal profile, which at times was biblically influenced. The large differences in PRP usage between the Book of Mormon and the King James Bible and pseudo-archaic works indicate a different authorial preference for these sets of texts — a preference that is mostly nonconscious, as shown by an inability of pseudo-archaic authors to sustain archaic/biblical usage over long stretches. The Book of Mormon is not a match with the usage in Joseph’s [Page 20]personal writings, as his own patterns fit comfortably in the late modern period, as do most contemporary pseudo-archaic works.

This point has been made in other contexts, including various iterations of stylometric analysis, but the force of the data is difficult to deny, even though it is based on only a single linguistic feature. (These PRP comparisons are in effect a kind of focused, precise stylometry.) Furthermore, the data lead us clearly away from Joseph as author or English-language translator and toward a specific time period — the only time when we find textual matching with the Book of Mormon’s archaic PRP distribution rates: the early modern era, and primarily the second half of the 1500s and the first decade of the 1600s. The textual evidence establishes the early modern period as the best and only fit for these Book of Mormon patterns. Indeed, the early modern sensibility of this aspect of the syntax is undeniable. These distinctive PRP patterns as well as the text’s striking preference for finite clausal complementation and the archaic nature of the verbal system, in all its complexity, go a long way toward establishing the vast majority of its syntax as early modern. This means that Book of Mormon content occurs within a framework of mostly early modern syntax.

A reviewer noted that this evidence favors Book of Mormon authenticity over the idea that the text was a flight of Joseph Smith’s fancy, but was interested in finding a reason for the divergent “he that” ~ “they which” usage. This syntactic pattern is not a calque of Hebrew usage, nor is the broader pattern, as classical/biblical Hebrew did not have three synonymous PRPs. What we encounter in the original Book of Mormon text is a less-common pattern of Early Modern English. Furthermore, it has been noted that positing a simple singular–plural that ~ which distinction fails to explain the data as well.

Obviously, this is a data-driven effort to catalog and accurately characterize the original English usage of the Book of Mormon text in this domain. The comparative project as a whole reveals the clear presence of many nonbiblical, early modern elements and patterns. I prefer to avoid speculation here and will simply note that one of the important side effects of the nonbiblical, archaic syntax and lexis is to rule out Joseph Smith as the author. While we may not know why the Book of Mormon is the way it is, we can assess what it is and what it is not, based on data. And the data consistently show unexpected archaic elements that undermine theories that Joseph Smith was the one who worded the translation.

[Page 21]Unless we accept that Joseph consciously and dramatically altered his native PRP pattern during the 1829 dictation in a sustained fashion, as no known pseudo-archaic author did, then we can conclude that he did not select these relative pronouns for the Book of Mormon in more than 1,600 instances. By extension, unless we want to assume that Joseph’s control of the text continually shifted during the dictation, we should conclude that he was not directly responsible for wording the text, in almost every instance. A considerable amount of additional syntactic and lexical evidence supports this view.

Appendix:

The Pseudo-Archaic Corpus

A pseudo-archaic text is one in which an author attempted to emulate earlier English usage or King James style — including syntax and lexical usage — in writing a history or related work. Scriptural-style texts of widely varying lengths were popular from about the mid-1700s into the 1800s, in both the British Isles and America.

In order to make the corpus of 25 pseudo-archaic writings, I first consulted Eran Shalev’s article on pseudo-biblicism32 and the following website: https://github.com/wordtreefoundation/books (contributors: Duane Johnson, Matt White, and Chris Johnson). Then I communicated with Shalev and Duane Johnson by email, asking them whether they knew of other pseudo-archaic texts. In the process, I added a few other texts that I found on my own or that I saw mentioned online. My current corpus has longer texts up to 1863, 34 years after the Book of Mormon was set down in writing. It is more likely to be deficient in shorter pseudo-archaic texts, as there are probably many very short pseudo-archaic writings in early newspapers. Yet these are much less important for purposes of comparison with the Book of Mormon, since for the most part we are interested in sustained usage and patterns, which the shorter texts cannot provide.

[Page 22]Here is a list of the pseudo-archaic texts examined for purposes of comparing subordinate that usage; these 25 texts contain approximately 585,000 words total:

Longer pseudo-archaic texts (12)

- Robert Dodsley, Chronicle of the Kings of England (1740) [London] [about 16,500 words]

- Jacob Ilive, The Book of Jasher (1751) [London] [about 22,800 words]

- John Leacock, American Chronicles (1775) [Philadelphia] [about 14,500 words]

- Richard Snowden, The American Revolution (1793) [Philadelphia] [about 49,300 words]

- Matthew Linning, The First Book of Napoleon (1809) [Edinburgh] [about 19,000 words]

- Elias Smith, History of Anti-Christ (1811) [Portland ME] [about 15,000 words]

- Gilbert Hunt, The Late War (1816) [New York] [about 42,500 words]

- Roger O’Connor, Chronicles of Eri (1822) [London] [about 131,700 words]

- W. K. Clementson, The Epistles of Ignatius and Polycarp (1827) [Brighton UK] [about 18,000 words]

- Philemon Stewart, Sacred Roll (1843) [Canterbury NH] [about 62,000 words]

- Charles Linton, The Healing of the Nations (1855) [New York] [about 111,000 words]

- Richard Grant White, The New Gospel of Peace (1863) [New York] [about 59,000 words]

Shorter pseudo-archaic texts (13)

- Horace Walpole, Book of Preferment (1742) [London] [about 2,700 words]

- The French Gasconade Defeated (1743) [Boston] [about 900 words]

- Benjamin Franklin, Parable Against Persecution (1755) [Philadelphia] [about 400 words]

- Chronicles of Nathan Ben Saddi (1758) [Philadelphia] [about 3,000 words]

- [Page 23]Samuel Hopkins, Samuel the Squomicutite (1763) [Newport RI] [about 600 words]

- The Book of America (1766) [Boston] [about 2,500 words]

- Chapter 37th (1782) [Boston Evening Post] [about 600 words]

- Chronicles of John (1812) [Charleston SC?] [about 800 words]

- The First Book of Chronicles, Chapter the Fifth (1812) [The Investigator, SC] [about 1,800 words]

- Jesse Denson, Chronicles of Andrew (1815) [Lexington KY] [about 4,800 words]

- White Griswold, A Chronicle of the Chiefs of Muttonville (1830) [Harwinton CT] [about 900 words]

- Reformer Chronicles (1832) [Buffalo NY] [about 700 words]

- Chronicles of the Land of Gotham (1888) [New York] [about 1,300 words]

Methodology

Personal relative pronoun usage can be broken down in many different ways. For instance, it can be broken down according to the antecedent involved and whether the relative pronoun is restrictive or nonrestrictive33 and whether the relative functions as a subject pronoun or an object pronoun. I did not differentiate on the basis of subject/object function for this study, but I did focus on restrictive contexts.

For a number of the PRP comparisons, I targeted the following high-frequency antecedents: those, they, them, he, him, man, men, people, you, ye, many, some, one, brother, brethren, and prophet(s). Contexts were targeted where the PRPs were immediately adjacent to these antecedents, without intervening punctuation, as a way to screen out many false positives. Consequently, the vast majority of the PRPs ended up being restrictive. With these constraints on searches, occurrences of personal that, which, and who(m) were separately tallied.

In the case of the King James Bible,34 the 25 pseudo-archaic texts, and Joseph’s early writings, false positives were deleted by inspection. In the case of the Book of Mormon, no false positives had to be deleted by inspection, since a text tagged for part of speech was used, with all the PRPs specifically tagged. Thus, the only potential false positives were where a PRP tagging error might have affected a targeted context.

Two sets of PRP rates were calculated for the Book of Mormon and the early writings: the complete rates given first in this paper, and rates derived from a subset of their usage, as described immediately above. This was done for purposes of making the remaining comparisons align [Page 24]with each other. The subset turned out to be a little more than half their total PRP usage.

Data

Table 4 shows the PRP profiles, rates, and chi-square tests for the King James Bible, the Book of Mormon, and 12 longer pseudo-archaic texts. In this case, contexts involving a limited number of high-frequency antecedents were counted. However, the two rows at the bottom marked “complete” include all known PRPs, except those that occur in longer biblical quotations. Those two data sets have only been compared against each other, showing the distinctness between Joseph Smith’s and the Book of Mormon’s usage distribution.

Table 4. PRP usage compared — chi-square tests based on raw numbers.

| that | which | who(m) | TOTAL | KJB Χ² | BofM Χ² | JS-EW Χ² | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King James Bible (1611) | 2750 | 325 | 119 | 3194 | |||

| Book of Mormon (1829) | 259 | 437 | 141 | 837 | 2E-232 | ||

| Early Writings (1829-1833) | 6 | 1 | 28 | 35 | 2E-101 | 1E-19 | |

| Chronicle of the Kings (1740) | 10 | 0 | 5 | 15 | 1E-08 | 0.0003 | 0.003 |

| Book of Jasher (1751) | 12 | 0 | 21 | 33 | 3E-62 | 1E-12 | 0.14 |

| American Chronicles (1775) | 19 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0.001 | 2E-07 | 5E-06 |

| American Revolution (1793) | 16 | 0 | 112 | 128 | 1E-290 | 5E-64 | 0.12 |

| Napoleon the Tyrant (1809) | 4 | 0 | 19 | 23 | 7E-76 | 6E-15 | 0.72 |

| History of Anti-Christ (1811) | 5 | 0 | 45 | 50 | 2E-166 | 5E-34 | 0.029 |

| Late War (1816) | 11 | 1 | 34 | 46 | 2E-108 | 3E-21 | 0.075 |

| Chronicles of Eri (1822) | 44 | 0 | 77 | 121 | 2E-164 | 1E-36 | 0.02 |

| Ignatius and Polycarp (1827) | 29 | 0 | 22 | 51 | 7E-42 | 1E-12 | 0.0008 |

| Sacred Scroll (1843) | 54 | 0 | 116 | 170 | 1E-225 | 9E-52 | 0.02 |

| Healing of the Nations (1855) | 18 | 0 | 159 | 177 | <1E-290 | 6E-83 | 0.04 |

| New Gospel of Peace (1863) | 85 | 38 | 87 | 210 | 2E-114 | 3E-21 | 0.0001 |

| Book of Mormon, complete | 370 | 939 | 300 | 1609 | 2E-29 | ||

| Early Writings, complete | 13 | 2 | 49 | 64 |

According to chi-square tests, no pseudo-archaic text came close to either the King James Bible or the Book of Mormon. As shown in Table 5, the closest texts have p-values of 0.008 and 0.0009, respectively. In contrast, most pseudo-archaic texts, when compared to Joseph Smith’s earlier writings, have p-values greater than 0.05.

Table 5. PRP usage compared —

chi-square tests based on modified totals (n = 50).

| [Page 25]that | which | who(m) | TOTAL | KJB Χ² | BofM Χ² | JS-EW Χ² | that | which | who(m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King James Bible (1611) | 2750 | 325 | 119 | 3194 | 86.1% | 10.2% | 3.7% | |||

| Book of Mormon (1829) | 259 | 437 | 141 | 837 | 2E-07 | 30.9% | 52.2% | 16.8% | ||

| Early Writings (1829-1833) | 6 | 1 | 28 | 35 | 2E-13 | 1E-10 | 17.1% | 2.9% | 80.0% | |

| Chronicle of the Kings (1740) | 10 | 0 | 5 | 15 | 1E-04 | 2E-08 | 3E-06 | 66.7% | 0.0% | 33.3% |

| Book of Jasher (1751) | 12 | 0 | 21 | 33 | 8E-10 | 2E-09 | 0.055 | 36.4% | 0.0% | 63.6% |

| American Chronicles (1775) | 19 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0.008 | 6E-09 | 5E-10 | 82.6% | 0.0% | 17.4% |

| American Revolution (1793) | 16 | 0 | 112 | 128 | 4E-16 | 2E-12 | 0.38 | 12.5% | 0.0% | 87.5% |

| Napoleon the Tyrant (1809) | 4 | 0 | 19 | 23 | 1E-14 | 2E-11 | 0.48 | 17.4% | 0.0% | 82.6% |

| History of Anti-Christ (1811) | 5 | 0 | 45 | 50 | 5E-17 | 5E-13 | 0.26 | 10.0% | 0.0% | 90.0% |

| Late War (1816) | 11 | 1 | 34 | 46 | 5E-12 | 1E-09 | 0.70 | 23.9% | 2.2% | 73.9% |

| Chronicles of Eri (1822) | 44 | 0 | 77 | 121 | 8E-10 | 2E-09 | 0.055 | 36.4% | 0.0% | 63.6% |

| Ignatius and Polycarp (1827) | 29 | 0 | 22 | 51 | 4E-06 | 2E-08 | 2E-04 | 56.9% | 0.0% | 43.1% |

| Sacred Scroll (1843) | 54 | 0 | 116 | 170 | 8E-11 | 9E-10 | 0.13 | 31.8% | 0.0% | 68.2% |

| Healing of the Nations (1855) | 18 | 0 | 159 | 177 | 6E-17 | 6E-13 | 0.27 | 10.2% | 0.0% | 89.8% |

| New Gospel of Peace (1863) | 85 | 38 | 87 | 210 | 4E-06 | 0.0009 | 3E-04 | 40.5% | 18.1% | 41.4% |

| Book of Mormon, complete | 370 | 939 | 300 | 1609 | 2E-29 | 23.0% | 58.4% | 18.6% | ||

| Early Writings, complete | 13 | 2 | 49 | 64 | 6E-10 | 20.3% | 3.1% | 76.6% |

Doctrine and Covenants Comparisons

A reviewer asked for additional comparisons to be done between the PRP usage of the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith’s early writings and early Doctrine and Covenants revelations. The assumption of most Latter-day Saint scholars is that Joseph Smith worded Doctrine and Covenants revelations.35 The way to determine whether this assumption is accurate is by thorough lexical and syntactic analysis, which to my knowledge has never been done, besides some initial work I began to do in this area a few years ago. Preliminary work suggests that it was unlikely that Joseph Smith worded many or most Doctrine and Covenants revelations.36 For example, section 9, which has no PRPs, has a few linguistic features that Joseph Smith was unlikely to produce in a pseudo-biblical effort. Because most Latter-day Saint scholars are convinced that Joseph Smith worded Doctrine and Covenants revelations, they think that the English usage of these revelations reflects his pseudo-archaic style. However, because that view has not been established and could very well be wrong, it is certainly wrong to proceed on that basis.

Doctrine and Covenants revelations present the analyst with various difficulties. I will mention two here. First, in many instances we do not have the original manuscripts, and so we cannot be sure of the original readings, especially when all we have in some cases are copies of copies. Some of what is extant shows that editing for style and grammar occurred in the copying process. Second, the individual revelations are short and [Page 26]their textual histories are unique and their PRP profiles are very limited and often dissimilar. All this makes statistical comparisons less reliable and less consequential.

In any event, I compared the complete PRP profiles of the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith’s early writings with the complete PRP profile of the earliest full versions of early Doctrine and Covenants revelations, from section 3 to section 19 (n = 50).37 I also compared these profiles with the complete PRP profile of the King James version of Genesis. The p-values of chi-square tests show that the pattern found in the earliest full versions of early Doctrine and Covenants revelations is statistically indistinguishable from that of the Book of Genesis (n = 148; Χ² ≈ 0.88, p ≈ 0.64). In contrast, the early D&C PRP pattern is not statistically similar to that of the Book of Mormon (n = 1,609; Χ² ≈ 22.9, p ≈ 1×10–5) and even more different from the PRP pattern of Joseph Smith’s early writings (n = 64; Χ² ≈ 35.7, p ≈ 2×10–8). These results, though their reliability is low, tend to reinforce the views expressed in this paper. In addition, Joseph Smith’s PRP pattern compared to that of the Book of Genesis is Χ² ≈ 66.5, p ≈ 4×10–15, and the comparison of the Book of Mormon to the Book of Genesis is Χ² ≈ 41.6, p ≈ 9×10–10.

“Those <PRP>”

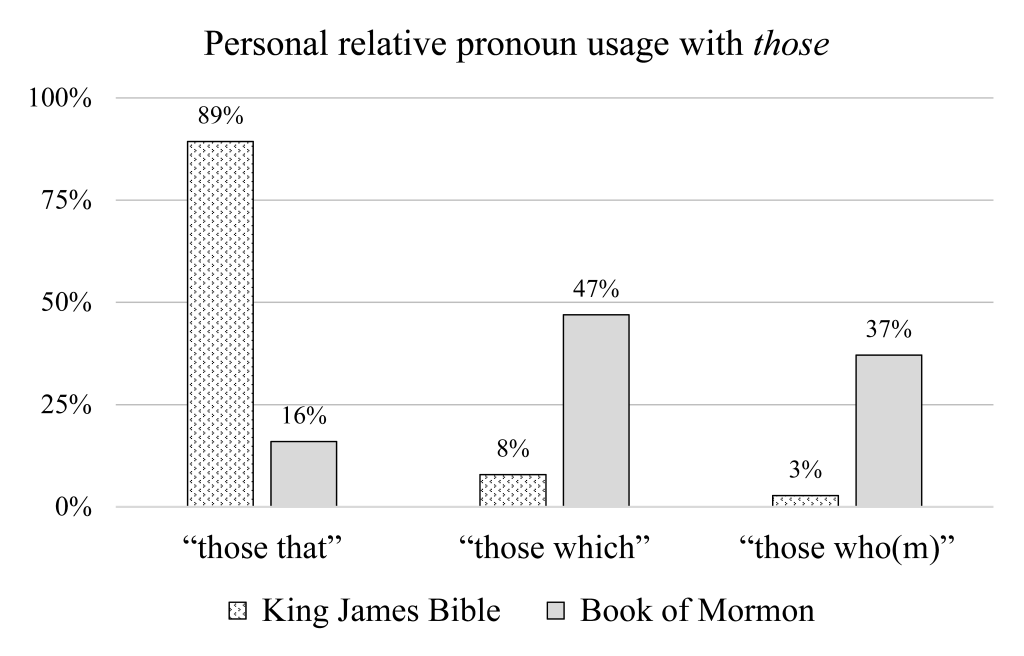

It is possible, of course, to focus on various subsets of the Book of Mormon’s PRP usage; one of these involves the antecedent those. The Book of Mormon has more than 200 instances of “those <PRP>,” as does the King James Bible, but their PRP profiles are clearly quite different, as shown in Figure 8.

In the case of the Book of Mormon, personal which is still dominant after those, but those who(m) exceeds those that, usage that is unlike its overall PRP profile.

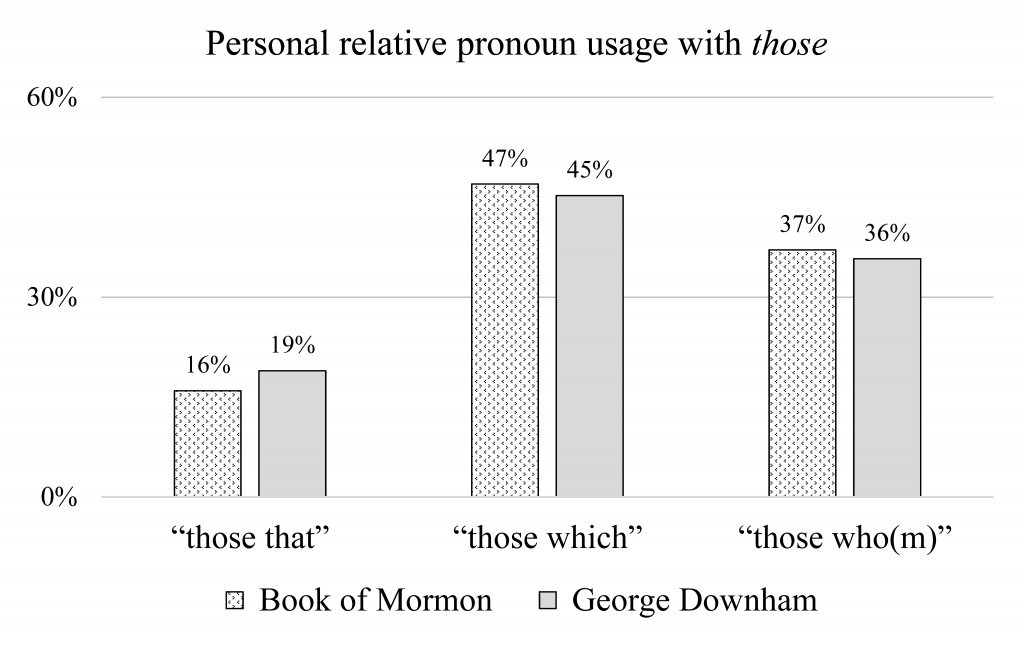

A search was made among EEBO Phase 1 texts to see if there were any that closely matched the Book of Mormon in this regard. It was found that most texts did not. Among the few potential candidates that did come up, George Downham wrote a book in 1611 (EEBO A20733) whose usage profile of “those <PRP>” turned out, after individual inspection, to closely match the profile of the Book of Mormon, a text produced 218 years later. The “those <PRP>” profile of Downham’s work is {that = 26, which = 62, who(m) = 49; n = 137}; the Book of Mormon’s profile is {that = 37, which = 100, who(m) = 79; n = 213}. These PRP profiles are quite similar, as shown in Figure 9.

[Page 27]

Figure 8. Comparison of “those <PRP>” in the Bible and Book of Mormon.

[Χ² ≈ 268.4, p ≈ 5×10–59; p ≈ 2×10–12 (n = 50)]

Figure 9. Comparison of “those <PRP>” in the Book of Mormon and

EEBO A20733 (1611). [Χ² ≈ 0.20, p ≈ 0.91; p ≈ 0.90 (n = 50)]

Here is an excerpt of Downham’s early 17th-century language, where we can read two instances of “those which,” usage that occurred in the dictation language of the Book of Mormon 100 times:

[Page 28]1611, A20733

to prescribe orders for amendment of life, to excommunicate those which willfully and obstinately resist, to receive into grace those which be penitent,

George Downham (sometimes spelled Downame) was originally from Chester and became bishop of Derry in 1616.

Comparing biblical and nonbiblical PRP rates

in the Book of Mormon

Examining the Book of Mormon’s biblical quotations, we find that the King James text clearly influenced PRP selection in those sections. This is the case even though a few instances of biblical personal that occurred as personal which in the dictation. As shown in Table 6, the influence is unmistakable because of the large difference in PRP distribution. This comparison supports the strong view that what we have in the Book of Mormon is biblical quoting, not biblical paraphrasing. In addition, because there is no support from the manuscripts or from dictation eyewitnesses that Joseph Smith used a King James Bible during the dictation, this is further indication that biblical material was transmitted to him in a pre-edited state.

Table 6. Comparison of biblical and nonbiblical PRP rates in the Book of Mormon.

| that | which | who(m) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biblical section | 70.9% | 23.6% | 5.5% | 199 |

| Nonbiblical sections | 23.0% | 58.4% | 18.6% | 1,609 |

| Χ² ≈ 200, p ≈ 3×10-44; p ≈ 0.0003 (n = 50). | ||||

| Note: | Most instances of personal which in the biblical quotations were edited for the 1837 edition to read who(m), even when personal which was the King James reading. See Royal Skousen, Grammatical Variation 1189ff for a complete listing of the edits. |

When a verb is complemented by a clause in finite form, that object clause has a finite main verb or auxiliary verb. An example of finite verbal complementation in the Book of Mormon is “he can cause the earth that it shall pass away” (1 Nephi 17:46). In this excerpt, the verb cause takes an object, “the earth,” and an object clause, “that it shall pass away.” This is a complex finite construction since there is an extra constituent before the that-clause. This structure is quite different from how we normally express this concept, which is with infinitival complementation: “he can cause the earth to pass away.”

See also examples of complex finite complementation in Royal Skousen, “The Language of the Original Text of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2018): 103–104, https://byustudies.byu.edu/article/the-language-of-the-original-text-of-the-book-of-mormon/.

Definition 1a for the verb translate in the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (CD-ROM, v4, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009) covers the Book of Mormon case; in the online third edition (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2021, https://www.oed.com/), it is found under definition 3a. Definition 4 of the third edition would also be applicable to a revealed-ideas approach. (Many OED definitions and numbering have been substantially changed in the online third edition.)

Here are the 82 texts that resulted from searching the EEBO corpus (r ≥ 0.9), listed in order of descending correlation (four are from the same author, Andrew Willet [1562–1621]): A18079 (1572), A19422 (1583), A15434 (1604), A19076 (1561), A15525 (1614), A37290 (1654), A21293 (1539), A33309 (1640), A21308 (1595), [Page 34]A08964 (1570), A93680 (1646), A43676 (1652), A92321 (1661), A06346 (1581), A06347 (1582), A01615 (1602), B23327 (1671), A69278 (1539), A03792 (1546), A15396 (1602), A17696 (1592), A10649 (1571), A14460 (1584), A00440 (1577), A19309 (1580), A14468 (1548), A12099 (1635), A07407 (1548), A15418 (1604), A10958 (1607), A17654 (1581), A20031 (1618), A05583 (1594), A61107 (1663), A12592 (1588), A19723 (1553), B00941 (1550), A19026 (1588), A18017 (1606), A05186 (1572), A05331 (1600), A15082 (1624), A10966 (1639), A06112 (1548), A13966 (1589), A37291 (1666), A15395 (1603), A16838 (1565), A09175 (1629), A04215 (1599), A17018 (1632), A15385 (1614), A19306 (1581), A03769 (1567), A14350 (1583), A67908 (1695), A47555 (1687), A13065 (1591), A14408 (1602), A00294 (1617), A89219 (1655), B12431 (1609), A08201 (1602), A15398 (1603), A19798 (1575), A18601 (1624), A10976 (1624), A06492 (1575), A17590 (1577), A17140 (1636), A58343 (1661), A07612 (1580), A14114 (1605), A57460 (1641), A43131 (1675), B09229 (1676), A17014 (1625), A67835 (1674), A14354 (1555), A13877 (1583), A09824 (1578), A04911 (1603). The earliest composition date is 1536 and the latest composition date is 1676 (publication dates range between 1539 and 1695).

Go here to see the 8 thoughts on ““Personal Relative Pronoun Usage in the Book of Mormon: An Important Authorship Diagnostic”” or to comment on it.