[Page 187]Abstract: Google’s Ngram Viewer often gives a distorted view of the popularity of cultural/religious phrases during the early 19th century and before. Other larger textual sources can provide a truer picture of relevant usage patterns of various content-rich phrases that occur in the Book of Mormon. Such an approach suggests that almost all of its phraseology fits comfortably within its syntactic framework, which is mostly early modern in character.

During the past decade, with the advent of Google’s Ngram Viewer (books.google.com/ngrams), many have become interested in noting the historical (textual) popularity rates of various cultural, content- rich Book of Mormon phrases such as “demands of justice.” Some have concluded by what they have seen in Ngram Viewer charts that the evidence suggests the Book of Mormon is 19th-century in character and that Joseph Smith was the author or the partial author of the text (from revealed ideas).1 My purpose here is to show that this recently developed interpretive tool is quite often misleading in relation to the Book of Mormon and that it’s important to reserve judgment on historical usage patterns until multiple textual sources have been consulted. It’s also important to recognize the type of language can tell us something definitive about Book of Mormon authorship and the fundamental nature of its language.

A database such as Google Books, which contains a large number of religious writings, is potentially an appropriate corpus to use in comparing Book of Mormon English. That is because, though dictated, the Book of Mormon text presents itself as a written translation of authors and editors who also wrote out their compositions (though [Page 188]some chapters are said to be transcripts of oral discourse). The narrative complexity, matching internal references, exact phrasal repetition (sometimes at a distance), intricate structuring (both large- and small-scale), and even instances of syntactic complexity suggest a primarily written work rather than a primarily oral production.

Because the text is full of biblical blending and religious language set in a framework of mostly early modern syntax, the Early English Books Online database2 provides the largest amount of matching language — religious, lexical, and syntactic. EEBO contains many religious writings, including sermons as well as the early biblical texts [1530–1610]. After EEBO, the next most relevant database for comparison is Eighteenth Century Collections Online.3 After EEBO and ECCO, the most relevant corpora are probably Google Books4 and the early American databases, Evans and Shaw-Shoemaker (these also contain many British writings republished in America, overlapping with content found in ECCO and even EEBO).5

On Content-Rich and Content-Poor Language

Before considering the data, some general comments are in order about the implications of two types of textual evidence: cultural, religious phrases (content- rich) and syntax (content-poor). It’s helpful to bear in mind that cultural, religious language occurs within a syntactic framework. These are separable objects of study: it is a straightforward matter to abstract away from either one in order to carry out linguistic and literary analysis.

Content-rich phrases like “demands of justice” involve a high degree of conscious thought in their production, while content- poor phraseology like “the more part” is chiefly the result of nonconscious production. Because authors do not consciously control what they nonconsciously [Page 189]produce, they reveal their native-speaker preferences in their (content-poor) syntax. Consciously produced content varies greatly in frequency according to context and subject matter and genre. In contrast, the frequency of syntactic usage is less influenced by these things (although some aspects of syntactic usage are affected by context, subject matter, and genre, such as which tenses are predominantly used). There are many generalizable usage patterns that can be analyzed and compared. Because a large amount of syntax is visible in the verbal system, studying the verbal system is of paramount importance.

A late-modern view of the Book of Mormon’s cultural, religious phrases tends to be popular in the literature. Such phrases, however, are unable to establish either the fundamental character of the language or that Joseph Smith was the author of the Book of Mormon. The suggestion that content-rich phrases are dispositive evidence for determining these things stems from inadequate reflection on details and implications of natural language production. It is the syntactic building blocks of language that indicate the fundamental character of textual language. When it comes to determining Book of Mormon authorship, content-rich phrases are overruled by the syntax. The latter indicates that most of its language is early modern in character and that Joseph wasn’t the author or partial author.6

A phrase examined below, “demands of justice,” is a cultural and religious phrase that has been used in a relatively limited set of writings and contexts. It provides a substantial amount of meaning independently. Another phrase considered below, “the more part,” is a content-poor phrase that had the potential to be used in a relatively large number of writings and contexts. There is a significant difference between these two types of language in terms of their diagnostic value in relation to determining Book of Mormon authorship. Specifically, the phrase “demands of justice” is a persistent phrase that arose in the early [Page 190]modern era, while more part phraseology (the non-adverbial type) did not persist robustly past the late 1600s, although we do see some related, vestigial use in the late modern era (some of this is discussed toward the end of this article).

Consider also the phrase “plan of destruction” (3 Nephi 1:16). This is a late-appearing phrase, textually speaking — it is currently first attested in 1768.7 But “plan of destruction” was conceptually part of English a century earlier, since the structurally and semantically similar phrases “plan of peace,” “plan of religion,” “plan of doctrine,” and “plan of (our) redemption” did occur in the late 1600s. As a content- rich phrase, “plan of destruction” cannot overrule the diagnostic value of content-poor phraseology such as “the more part of X” (where X is a noun phrase) or “of which hath been spoken”. These are less contextually dependent and were in obsolescence at the beginning of the late modern period. This makes the presence in the Book of Mormon of the comparative phraseology “the more part of X” and the referential phraseology “of which/whom «be»8 spoken” diagnostically important. (Ten of eleven instances of the referential phraseology are archaic in formation; all instances of more part phraseology are nonbiblical in formation.) It also means that the presence of language like “plan of destruction” is mostly diagnostically unremarkable.

- Cultural, religious phrases:

high degree of contextual dependence

low usage rates (on balance)

provide little information about nonconscious native-speaker tendencies - Content-poor syntax:

low degree of contextual dependence

potential for much higher usage rates

reveals nonconscious native-speaker tendencies

The Google Books Database

The very creators of the Ngram Viewer have pointed out the risk for their charts to mislead analysts vis-à-vis earlier cultural trends. According [Page 191]to them, the popularity trends of 18th-century cultural phrases are particularly susceptible to being misstated in the charts.9 Others have mentioned that this is the case even for early 19th-century trends,10 once again citing the published papers of the Ngram Viewer creators. This is because of the limitations of the underlying Google Books database.

It’s important to note that the Viewer can be less misleading in relation to syntactic studies involving content-poor phrases. Such phrases have the potential to be more heavily represented in the underlying data. As a specific example, we are more likely to get an accurate picture of popularity in comparing usage rates of the infinitive construction “caused <object pronoun> to” with the finite construction “caused that <subject pronoun>” than in looking at the trajectory of “demands of justice” (shown below).

As mentioned, the Viewer is based on the Google Books database. This has only a fraction of the 18th-century coverage of the largest database, ECCO. The 18th-century Google Books portion is currently about 12 percent of the size of ECCO, and the first half of the 18th century is underrepresented compared to the second half of the 18th century. The underrepresentation of English usage in Google Books is even greater as we go back further in time to the early modern period (details shown below). This means that the Viewer is highly unreliable for the 16th and 17th centuries.

Unfortunately, the inevitable result of this underrepresentation is that charts are often generated by the data underlying the Ngram Viewer that do not accurately represent prior usage patterns. This is shown here by a comparison of Viewer charts with the charts provided by the ECCO database and with charts generated from a 740-million-word corpus that [Page 192]covers the years 1473 to 1700 (made from Phase 1 texts of the EEBO database).

Language Examined for this Study

I will briefly discuss the following six phrases and phrase types:

- “demands of justice” [first EEBO example is 1647]

- “first parents” [first EEBO example is 1483]

- “infinite goodness” [first EEBO example is 1479]

- “forbidden fruit” [first EEBO example is 1550]

- “plan of X” [first EEBO example is 1689; X = divinity]

- “the more part of X” [first OED example is 1398; X = the heritage]

Corpora Used in this Study

Here are the three corpora that generated the charts shown in this study, along with some relevant details:

- Google Books (sparse coverage up to the 18th century):

| 4.4 million | 16th-century words |

| 63.9 million | 17th-century words |

| 1.8 billion | 18th-century words11 |

| 49.5 billion | 19th-century words |

| 299.5 billion | 20th-century words |

- ECCO: 180,000 18th-century titles (as currently noted on the initial search page). From this number of titles and the number of 18th-century words in Google Books, we find that ECCO could have approximately 15 billion 18th-century words, with a large amount of duplication.

- EEBO (Phase 1 texts): approximately 740 million words in 25,367 texts, from the late 15th century through the 17th century. EEBO1 has almost 11 times the coverage of Google Books for the same time period, with high-quality transcriptions that are much more reliable.

[Page 193]Popularity Profiles of Six Nonbiblical Book of Mormon Phrases

“Demands of justice” [1647 (earliest attestation)]

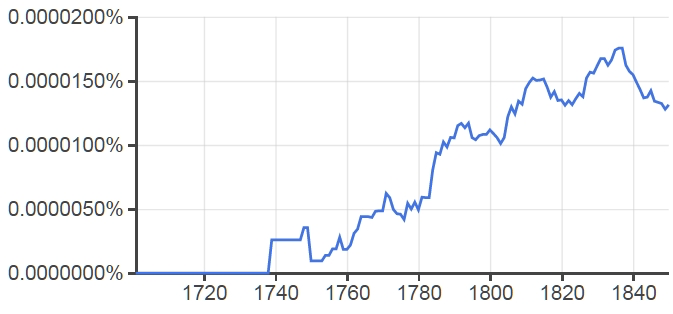

We begin our investigation of Book of Mormon phrases with the cultural, religious phrase “demands of justice,” a phrase that arose, textually speaking, in the middle of the 17th century. Because the Ngram Viewer is based on relatively sparse coverage of the first half of the 18th century, a misleading chart (Figure 1) is currently generated by the underlying data (the vertical axis gives word-occurrence rates; the values [very small] are irrelevant in the context of this paper).

Figure 1 leads us to believe that there was hardly any usage of the phrase “demands of justice” in the early 18th century. (In this study, I have mostly restricted Viewer charts to the 18th century and beyond, since the data coverage of the 16th and 17th centuries is relatively minimal, frequently generating charts with discontinuous spikes.)12 Because ECCO is based on more than eight times the number of titles, its term frequency chart is more reliable than the Viewer, though not entirely, since the later one goes in the 18th century, the more books are encountered with repeated language (which is also a problem with the Viewer). ECCO’s popularity chart helps in this regard, to some degree, since it can give users the percentage of documents per year that have a given word or phrase.

Figure 1. Ngram Viewer chart of “demands of justice.”

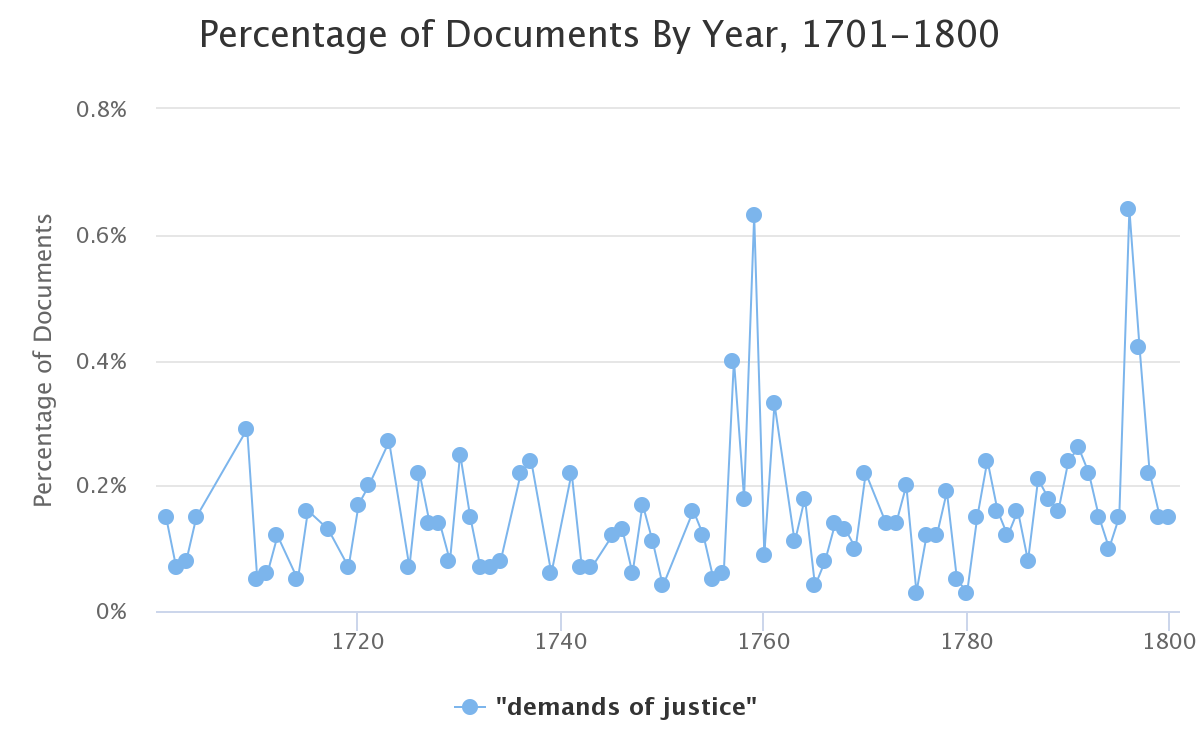

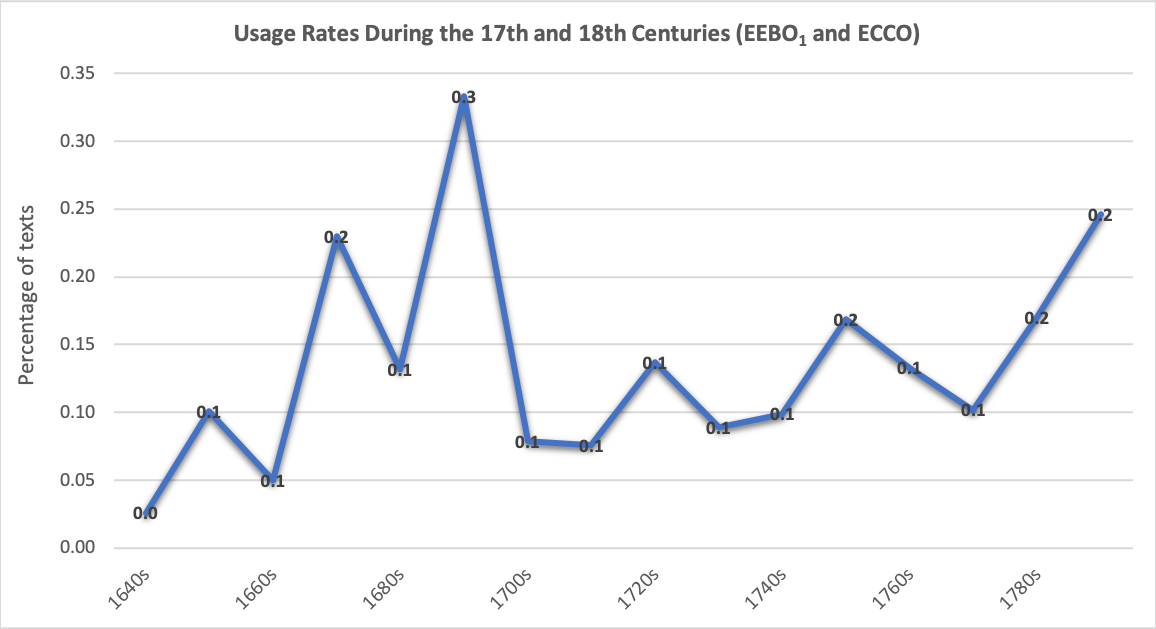

[Page 194]Figure 2 is an ECCO popularity chart of “demands of justice.”13 It clearly shows usage of the phrase in the first half of the 18th century and that there was only a slight upward trend during the entire century. Against what the Viewer indicates, there was no sharp upward trend from zero that began near the middle of the century. Moreover, if we look at an earlier corpus, EEBO, we find that in the publicly available Phase 1 portion of the database (EEBO1), 0.23 percent of the documents in the 1670s have the phrase “demands of justice” (6 of 2,608 documents) and that 0.33 percent of the documents from the 1690s have the phrase (10 of 3,006 documents). Figure 3 is a composite chart of the earlier usage rates, combining EEBO1 and ECCO data (from 1473 to 1800). It shows no clear increase in the popularity of the phrase “demands of justice” from the 1670s to the 1790s.

Figure 2. ECCO chart of “demands of justice.”

Figure 3. Combined EEBO1 and ECCO chart of “demands of justice.”

Consider too that popularity rates of uncommon content-rich phrases like “demands of justice” can vary greatly depending on the composition of the corpus — that is, the weighting of the genres in the corpus. In this case, if the corpus has a large percentage of religious texts or legal texts, then the popularity rate of “demands of justice” has the potential to be higher. If not, popularity rates will be lower. In contrast, content-poor syntactic phrases have a greater potential to give a truer [Page 195]picture of past usage rates and popularity. The genres represented in the corpus are less important in the case of such phrases, though not always of no consequence.

The first appearance of the phrase “demands of justice” in EEBO occurs in 1647 (A57963, page 66). The earliest occurrences of phrases are among the most interesting to consider. Beyond showing authorial creativity, in the case of potentially inspired religious language, they are more likely to be the result of divine influence than later instances, which are more likely to be influenced by earlier usage. In this case, the 1647 author of “demands of justice,” Samuel Rutherford, a delegate to the Westminster Assembly (a multi-year Church of England reform council), provides not only this content-rich coincidence with Book of Mormon usage, but also examples of extrabiblical syntactic usage and variation found in the earliest text, such as archaic “because that S1 and that S2” usage (1648, EEBO A57980; 1 Nephi 2:11, Jacob 5:60) and nearby ye was ~ ye are variation (1664, A57970; Alma 7:18–19; also we was ~ we are: 1652, A57982).

Of the four instances of “demands of justice” found in the Book of Mormon, the last one occurs closely with two instances of the phrase “plan of mercy” (Alma 42:15). This language is currently first attested in 1746, but it would not have clashed with late 1600s language, since a few different “plan of X” phrases are attested beginning in the late 1680s. The adjective phrase “perfect just” occurs right after “demands of justice,” [Page 196]meaning ‘perfectly just’; it provides a good example of characteristically early modern syntactic usage in which the adverb lacked the {-ly} suffix. In EEBO1, “perfect just” (without intervening punctuation) occurs 16 times, at a higher rate in the 16th century than in the 17th century (five times the rate; see Figure 4). Another syntactic item in this verse involves a subordinate clause headed by except with the conditional auxiliary verb should, usage that was also more characteristic of the 16th century than the 17th century (peaking textually in the 1550s; see Figure 514). Overall, the language in this passage doesn’t clash, and there are stronger reasons to classify it as early modern in character than late modern.15

Figure 4. EEBO1 chart of “perfect just.”

Figure 5. EEBO1 chart of “except

“First parents” [1483]

The next phrase we’ll consider is another nonbiblical one, “first parents.” The phrase occurs 13 times in the Book of Mormon, first at 1 Nephi 5:11. It is used there with some archaic syntax: “Adam and Eve, which was our first parents.” This syntax corresponds precisely with the usage of Thomas Becon in 1566: “Adam and Eve, which was made of the ground.” Becon also used “first parents” in 1542 (A06719). We encounter many such coincidences in the Book of Mormon, as in this case and the case of the writings of Samuel Rutherford. EEBO1 has thousands of examples of the phrase “first parents,” including four from the 1480s alone.

[Page 197]According to an ECCO popularity chart, the usage rate of “first parents” didn’t change that much over the course of the 18th century, ranging between three and six percent, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. ECCO chart of “first parents.”

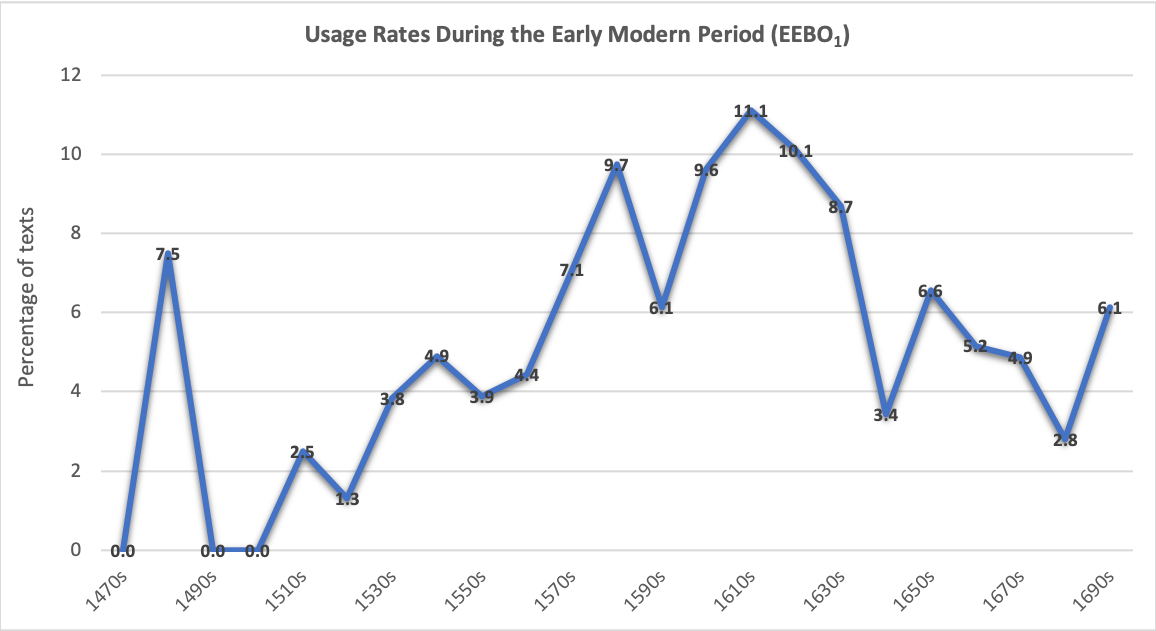

But according to the Viewer, the usage rate of “first parents” rose significantly during the 18th century, and at the beginning of the 19th century, the usage rate appears to have surged to its highest levels (see Figure 7). EEBO Phase 1 texts, however, indicate an absolute peak popularity in the 1610s (eleven percent of texts; see Figure 8). This is [Page 198]a figure significantly above the four percent of the 1790s that ECCO indicates.

Figure 7. Ngram Viewer chart of “first parents.”

Figure 8. EEBO1 chart of “first parents.”

Some of the rise we see between 1801 and 1830 in the Viewer is a skewing brought about by later editions and the republishing of earlier texts, as previously mentioned. In any event, a doubling in the usage rate of “first parents” during the first three decades of the 1800s could have raised its per document rate to a maximum level of seven or eight percent. Based on current information, the 1610s is a stronger candidate for peak popularity of “first parents” than the early 1800s.

[Page 199]“Infinite goodness” [1479]

In a review of a text-critical publication on grammatical editing in the Book of Mormon, Grant Hardy lists 16 nonbiblical phrases that he says were commonly used in the 19th century, stating that “these do occur as early as the seventeenth century.”16 The phrase “as early as” most likely conveys ‘no earlier than,’ leaving readers with the sense that these phrases were most popular after the 17th century. One of the phrases in his list is “infinite goodness,” occurring at 2 Nephi 1:10, Mosiah 5:3, Helaman 12:1, and Moroni 8:3.

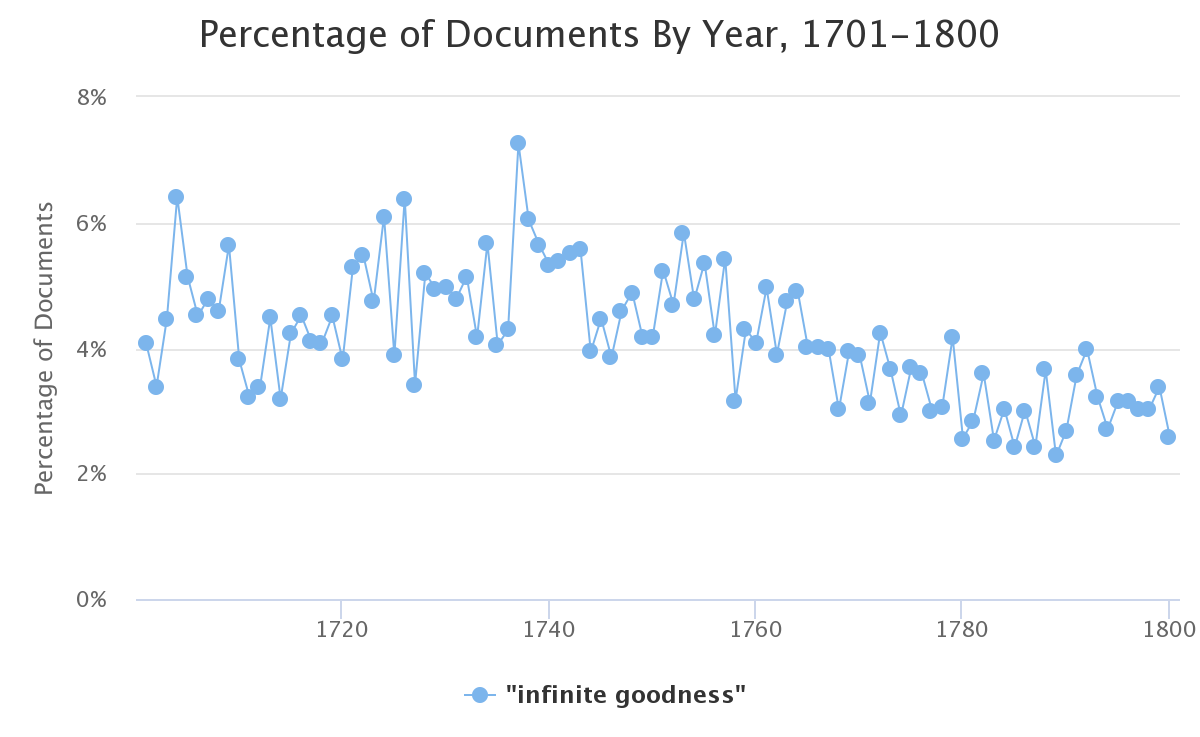

Hardy might not have consulted EEBO and ECCO, something that is necessary to do in order to determine when these phrases arose and to have any chance at accurately determining when they might have been most popular. It’s possible that he entered them into the Ngram Viewer and was misled by what he saw in the charts. Consider, for instance, a Viewer chart of “infinite goodness” between 1500 and 1830 (Figure 9). In this chart we see two early spikes based on seven results total. Then there is a continuous jagged rise, suggesting that the year 1830 was the height of popularity. This might have been as far as Hardy went in gauging the trajectory of this phrase’s textual popularity.

Figure 9. Ngram Viewer chart of “infinite goodness.”

An important issue when dealing with a phrase that might have arisen during the first half of the early modern period is spelling variation. In this case, there are six obvious variants of the word goodness to consider [Page 200]and more than that for the word infinite. This means, of course, that there are at least 40 possible spelling variants of the phrase, although the large majority of the potential spelling variants of the phrase probably never co-occurred in the textual record.

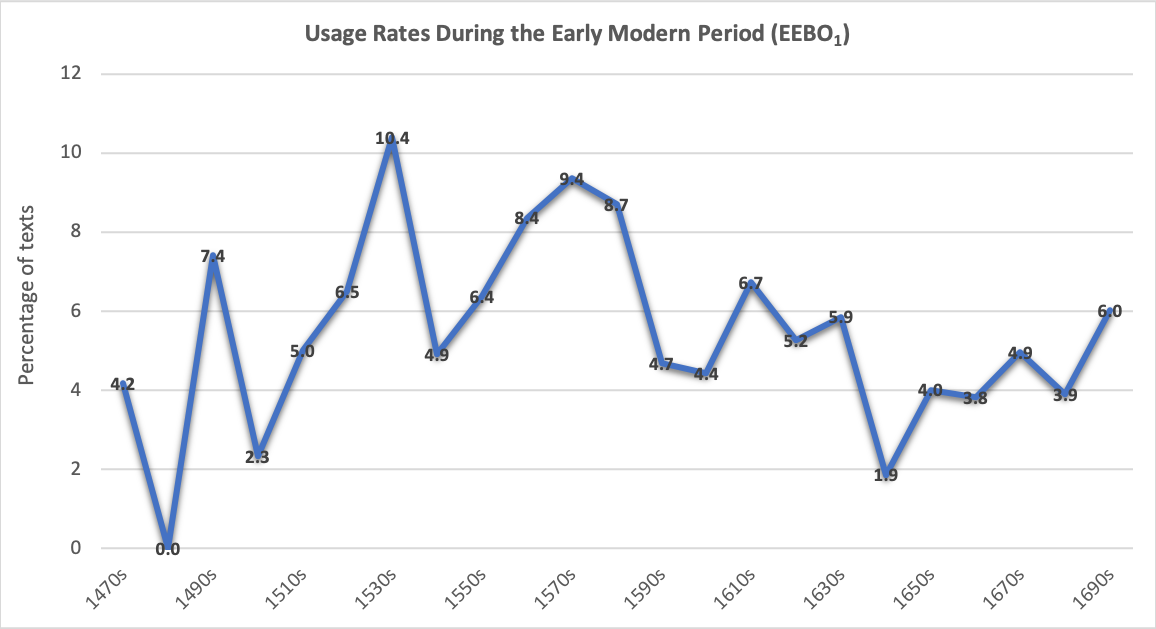

There is no easy way to enter so many variants in the Viewer, and there are large gaps in Google Books’ coverage for the earlier period, especially the 1500s (see above). So, we must go to EEBO, using spelling variants, in order to approach a sense of early modern popularity. This can only be easily done using a third-party EEBO corpus. It cannot be done using the EEBO website search page, since the search engine has difficulty with complicated wildcard searches. From a WordCruncher EEBO corpus17 we obtain the chart in Figure 10, showing usage rate per document. To complete the comparison, we consult an ECCO popularity chart of “infinite goodness” (Figure 11). Taken together, these charts indicate that the height of popularity of “infinite goodness,” textually speaking, was the 1530s or the 1570s.

Figure 10. EEBO1 chart of “infinite goodness.”

Figure 11. ECCO chart of “infinite goodness.”

The impression that Hardy gives his readers is that the 16 nonbiblical Book of Mormon phrases reached their height of popularity in the late modern period rather than the early modern period. We see that this is questionable for “infinite goodness” and “first parents” (another of his 16 phrases), and as it turns out, it’s questionable for more than half of the phrases.

Hardy’s statement that these phrases occur as early as the 17th century (taken to mean ‘no earlier than the 17th century’) might be inaccurate for 69 percent of the phrases. Here is his list, ordered according to date of first attestation in EEBO (mean date = 1565; median date = 1578):

[Page 201]1473 God of nature 1479 infinite goodness 1479 fall of man 1483 first parents 1532 sacrifice for sin 1538 Great Mediator 1552 temporally and spiritually

(as temporally, spiritually & eternally)[Page 202]1563 land of liberty 1574 final state 1582 workings of the Spirit 1583 instrument(s) in the hands of God 1606 watery grave 1637 miserable forever (as forever miserable) 1641 condescension of God 1652 cold and silent grave (as cold silent grave)

(cold grave: 1542; silent grave: 1590)1660 day(s) of probation

Only five of the 16 are first attested as late as the 17th century, and both cold grave and silent grave are first attested in the 16th century. So, it is accurate to state that only one-quarter of the phrases are first attested as late as the 17th century; the rest are attested earlier.

I ran numbers on all 16 of these phrases in EEBO1 and ECCO and obtained usage rate profiles and peaks. Here is a list of these same phrases with the decade of peak popularity shown (in the case of the two phrases with highest popularity in the late 1400s, I have also given the next highest decade). These phrases are ordered according to greatest early modern popularity when measured against their peak in late modern popularity:

Phrase Peak popularity (textual) temporally, spiritually 1580s God of nature 1480s, 1630s condescension(s) of God 1690s sacrifice for sin 1580s workings of the Spirit 1670s first parents 1610s infinite goodness 1530s final state 1650s fall of man 1470s, 1610s Great Mediator 1750s miserable forever / forever miserable 1760s instrument(s) in the hands of God 1790s cold grave & silent grave 1790s watery grave 1790s day(s) of probation 1760s land of liberty 1790s

[Page 203]The immediate co-occurrence of temporally and spiritually was most characteristic of the earlier period. The phrase “land of liberty” was most characteristic of the later period and especially the end of the 1700s. Nine of the 16 phrases turned out to be more popular during at least one decade of the early modern era than they were during any decade of the 18th century. In addition, “Great Mediator” and “miserable forever” ~ “forever miserable” weren’t strongly characteristic of the late modern period over the early modern period.

In summary, most of these phrases aren’t obviously characteristic of the early 19th century, and all of them fit comfortably within a framework of mostly early modern syntax.

“Forbidden fruit” [1550]

The nonbiblical term “forbidden fruit” occurs six times in the Book of Mormon (three times in close succession in 2 Nephi 2 [verses 15, 18, 19]; also in Mosiah 3:26, Alma 12:22, and Helaman 6:26). Here is one of the earliest dated examples of this phrase found in EEBO1:

1550, Thomas Becon, The flower of godly prayers [ A06743 ]

If through the subtle enticements of Satan, they had not transgressed thy commandment by eating the forbidden fruit, . . .

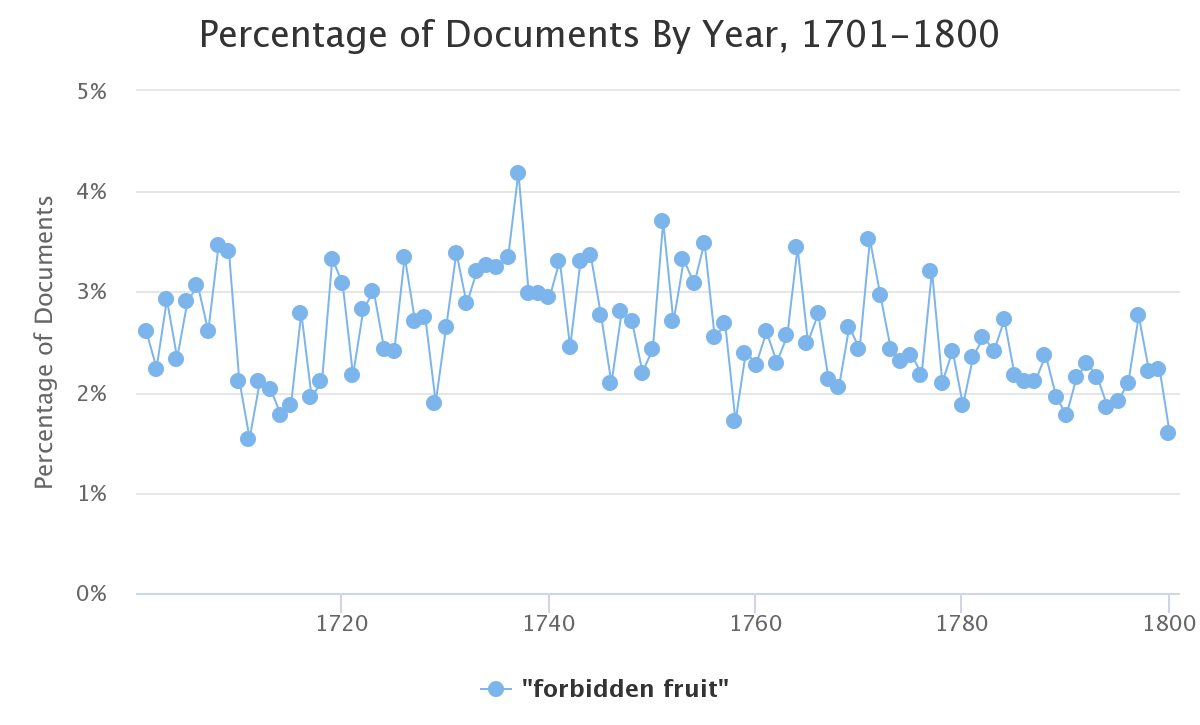

Figures 12 and 13 suggest that the height of popularity of the phrase “forbidden fruit” might have been during the first 40 years of the 17th century, not during the 18th century. The Viewer, however, when [Page 204]restricted to 1700 and later, leads us to believe that the popularity of the phrase “forbidden fruit” was greatest around the year 1810 (Figure 14).

Figure 12. EEBO1 chart of “forbidden fruit.”

Figure 13. ECCO chart of “forbidden fruit.”

Figure 14. Ngram Viewer chart of “forbidden fruit.”

“Plan of X” phrases [1689]

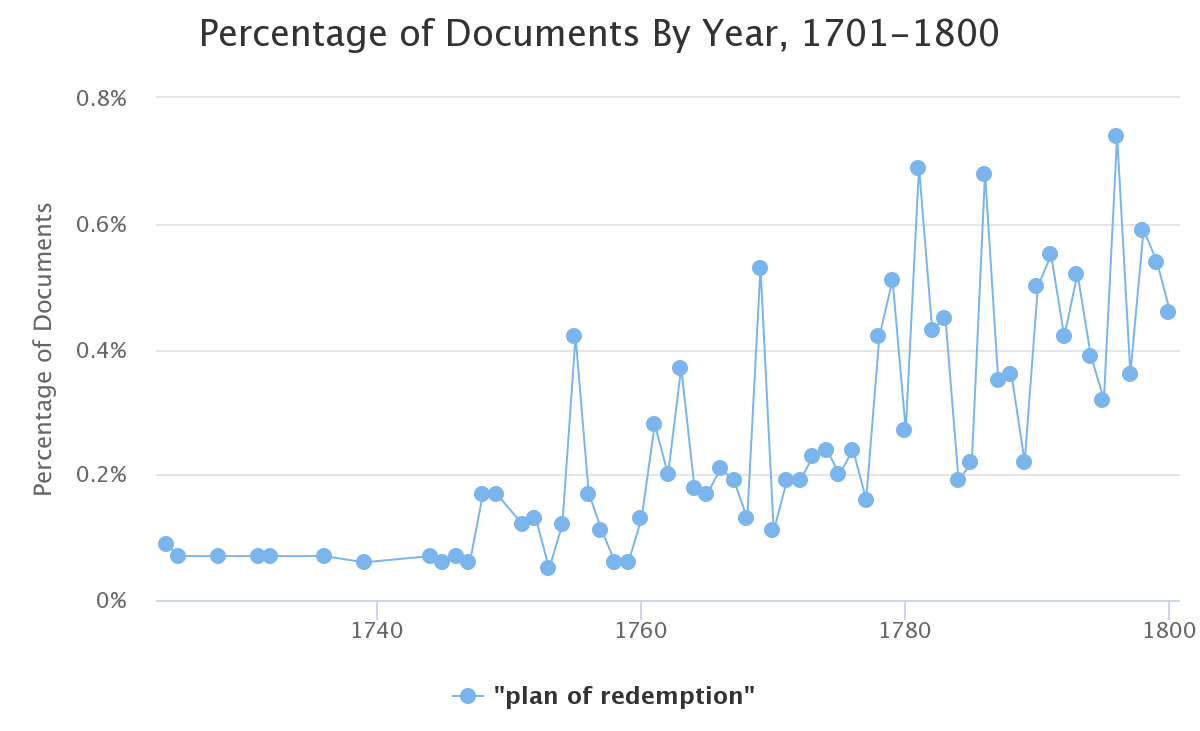

Textually speaking, some Book of Mormon phrases were more popular or appear to have been more popular in the 18th century than in the 17th century. One set of phrases that occurred more frequently in the 18th century than in the 17th century is “plan of X” phrases. Most of these, though conceptually in the language by the late 17th century, are [Page 205]not attested until the early 18th century.18 So the Book of Mormon’s six types of “plan of X” phrases could not have been more frequent in the 17th century than in the 18th century, since there is hardly any textual usage in the 17th century.

The most common of the Book of Mormon’s “plan of X” phrases, “plan of redemption,” was the one that occurrred earliest. It appears first in the 1690s (as “plan of our redemption,” in 1697). This phrase appears in nearly 500 ECCO documents (this database primarily covers the years 1701–1800). Figure 15 is an ECCO popularity chart of the simple phrase “plan of redemption.” It shows a rise in the usage rate (per document) from zero percent to half a percent (on average). Nevertheless, because the few exclusively 18th-century phrases of the Book of Mormon are enveloped in early modern syntax, they do not change the conclusion that one could reasonably reach about the fundamental character of its language and whether Joseph Smith could have authored it.

Figure 15. ECCO chart of “plan of redemption.”

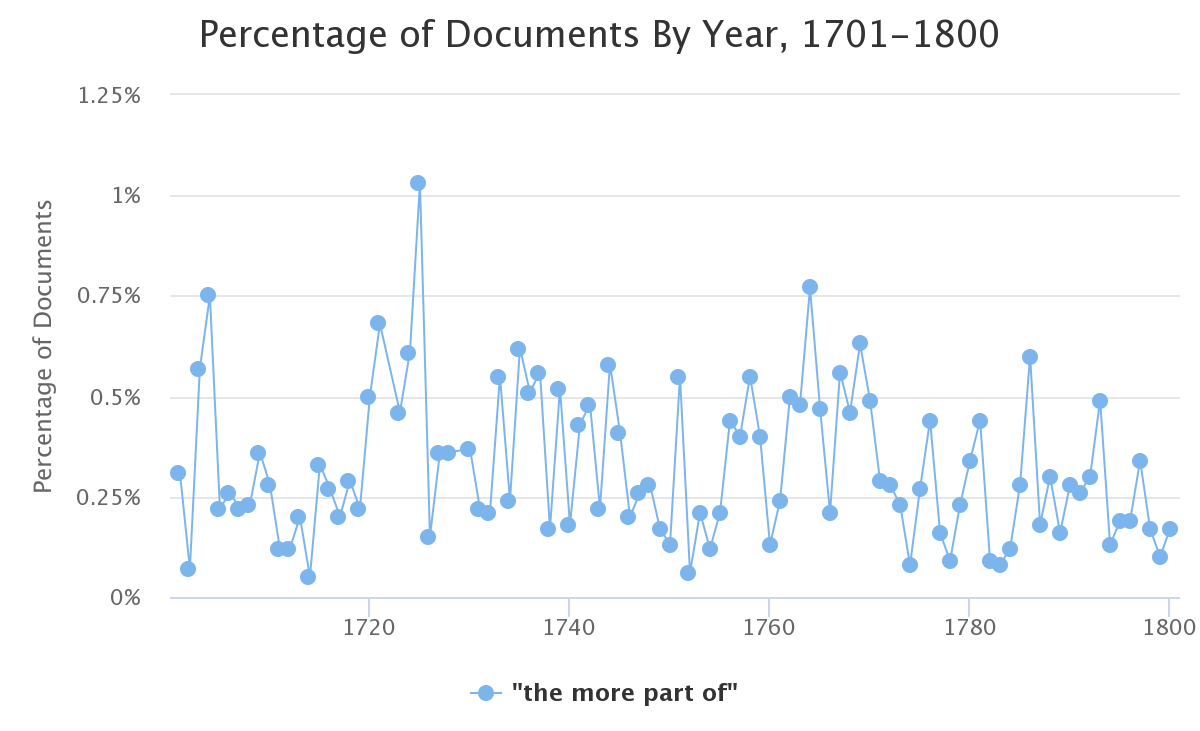

“The more part of X” [1398]

The Book of Mormon has almost two dozen instances of the phraseology “the more part of X.” It also has two instances of the adverbial constituent “for the more part” and two textually rare, exclusively [Page 206]early modern variants: “a more part of X” and “the more parts of X” (three instances total). The King James Bible only uses the unmodified phrase “the more part” twice (Acts 19:32; 27:12). The Book of Mormon doesn’t have this biblical usage.19 Setting aside the three minor variants of the phraseology, the 21 instances of “the more part of X” in the Book of Mormon are quite possibly the most that had appeared in a single text in 253 years, since Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577), which has 90 of the form “the more part of X” (in almost 2.5 million words).

“The more part of X” is a good example of content-poor phraseology that had the potential to be used in many different contexts at relatively high rates. When we abstract away from the content-rich noun phrase X, we are able to investigate a content-poor phrase type that could have been used in a large number of contexts. It thus provides valuable information for classifying the nature of Book of Mormon language.

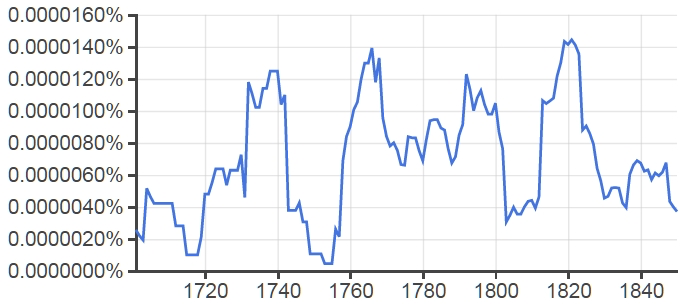

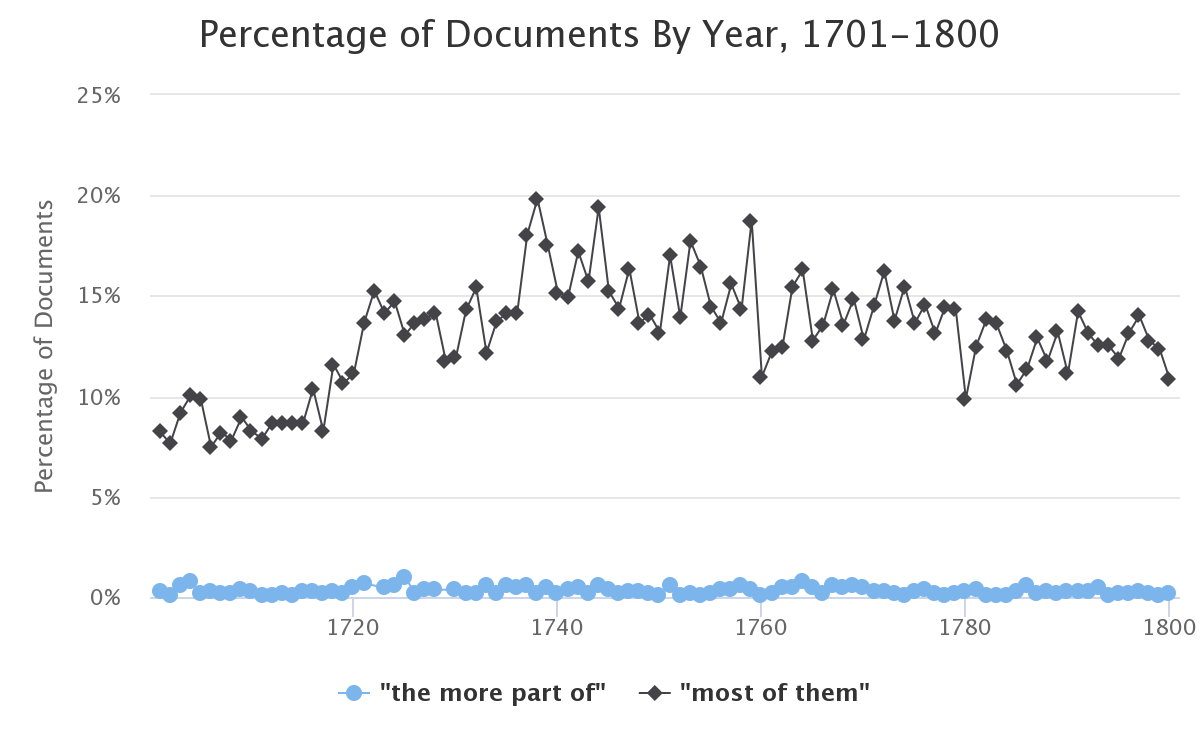

When we consider usage rates of this phrase at the beginning of the late modern period, we find that the Ngram Viewer indicates that there was mostly persistent usage throughout the 18th century, with a slight upward trend (Figure 16). ECCO’s popularity chart also shows a low level of use throughout the 18th century, without any discernible trend (Figure 17).

Figure 16. Ngram Viewer chart of “the more part of X.”

Figure 17. ECCO chart of “the more part of X.”

The reality, however, is that almost every 18th-century document contains examples of “the more part of X” only in passages with earlier, reprinted legal language, often from the 16th century and earlier. For example, the 14 documents published in 1725 (out of 1,310) with examples of “the more part of X” (the highest data point in Figure 17) contain instances found in earlier legal language.

Nevertheless, there is some original use of “the more part of X” in the 1700s. But there is very little, and it is hard to know how much there actually is. We would have to wade through more than 600 instances, using the difficult ECCO interface, in order to find perhaps two or three originals. (ECCO currently gives 624 results, with many duplicates.) One noteworthy case — a 1768 poetic example found in the online, third edition of the OED — does not reveal itself in ECCO searches, since “the more part of mankind” was transcribed by the optical character recognition (OCR) software as “the tnore part of mankind.” The entire poetic line is in italics, and as a result, the OCR software didn’t get the [Page 207]correct letters in the case of the word more. This means, of course, that these databases currently have some fundamental limitations. In the future, better databases will yield more reliable and useful results. (The EEBO database has a very low rate of transcription error, significantly lower than either ECCO or Google Books. This is because most of EEBO was not transcribed using OCR software.)

An ECCO popularity chart comparing “the more part of them” with “most of them” makes it clear that the latter was the operative phrase in the 18th century, not “the more part of them” (Figure 18). (The usage rate of “the majority of them” was also quite low during this century.) What [Page 208]looks like low-level modern usage of the archaic phrase is, in very large part, just noise emanating from reprinted language.

Figure 18. ECCO chart of “most of them” and “the more part of them.”

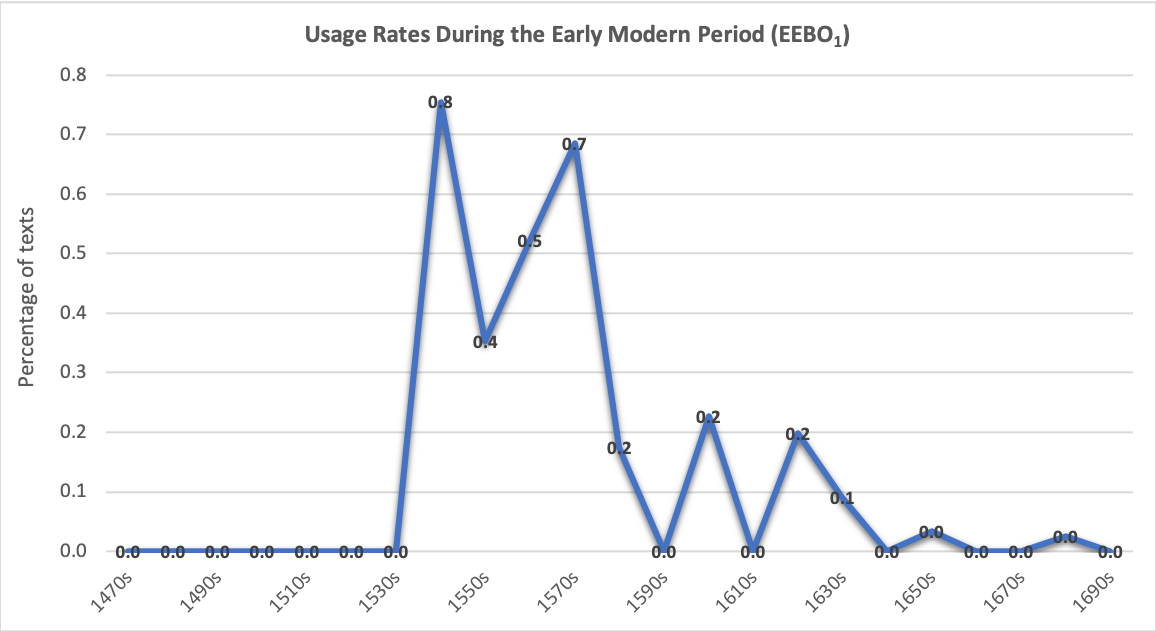

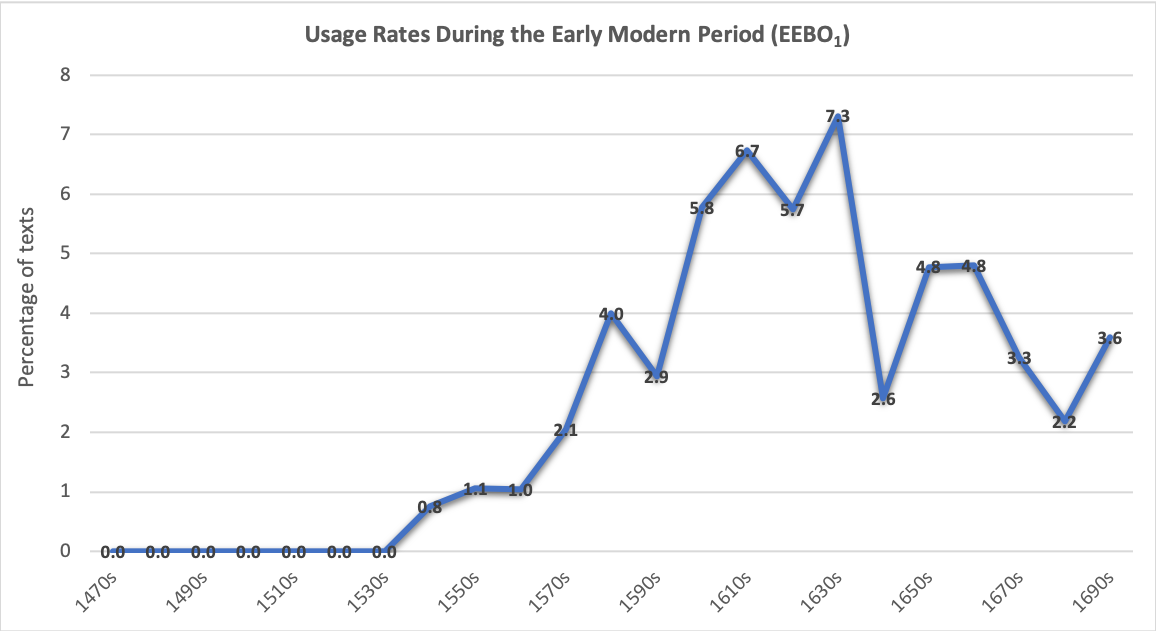

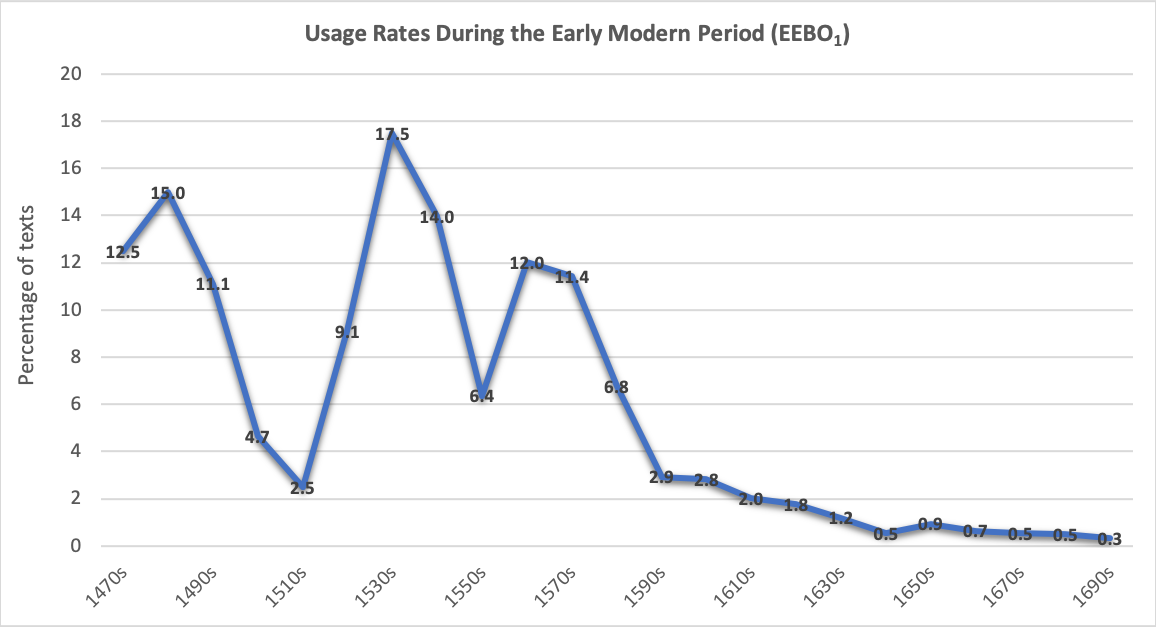

Figure 19 shows the usage rates of “the more part of X” during the early modern era. This indicates that it was primarily a phrase of the first half of the early modern period. By the 1590s, popularity of the phrase had dipped to such a degree that less than three percent of texts employed it during that decade (1591–1600, aligning the years with the century). Even this EEBO1 chart has some contamination in the late 1600s from reprinted language, but despite this it shows that usage of the phrase was close to zero in the 1690s. Only one EEBO1 text in the 1690s (the last decade of the early modern period) has an original instance of “the more part,” which is equivalent to a meager per document usage rate for that decade of just 0.03 percent.20 By that decade, “more part” phraseology was moribund. (Seven other potential examples from the 1690s were quotations of Acts 19:32 [2×], of earlier statutes [4×], and of a 16th-century author [1×].)21

Figure 19. EEBO1 chart of “the more part.”

[Page 209]The high levels of “more part” phraseology found in the Book of Mormon, its two rare variants, and Figure 19 indicate that the Book of Mormon’s usage of the phraseology is best characterized as early modern, not rare late modern.

Conclusion

Besides the importance of being aware of the potential pitfalls we can encounter in interpreting Ngram Viewer charts (and even sometimes ECCO’s term frequency charts), the conclusion to be drawn vis-à-vis Book [Page 210]of Mormon usage is that these charts, used in isolation, very often give us the wrong idea about earlier usage patterns and rates. As it turns out, the time depth of many content-rich phrases is often greater than first appears.

Here is the list of the phrases treated in this study, along with an indication of the relative popularity of these phrases (as currently indicated by raw, unfiltered textual data):

- “the more part of X” [popularity peaked in the 1530s]

- “infinite goodness” [popularity peaked in the 1530s

or the 1570s] - “first parents” [popularity peaked in the 1610s]

- “forbidden fruit” [popularity peaked in the 1630s]

- “demands of justice” [popularity peaked in the 1690s]

- “plan of X” [exclusively late modern, except for “plan of our redemption”]

Most content-rich phrases of the Book of Mormon fit well with its early modern syntax. There are some phrases that are properly classified, according to the general textual record, as characteristically late modern, but most phrases were found during the early modern period, and many of these might have seen peak popularity, or close to peak popularity, during that earlier time.

It’s possible that the easily accessible but unreliable information provided by Ngram Viewer charts has influenced the views of some Book of Mormon scholars. This information, colored by only a superficial consideration of its syntax, has led many to conclude that the original text is a mix of biblical language and 19th-century vernacular. Some have written or implied that this is the case, leaving many readers with the wrong impression of its English. Of course, such statements shouldn’t be made without undertaking a large amount of research in order to support them. Consequently, it would be wise to treat cautiously any comments made about the nature of Book of Mormon English until verifying that the maker of the comments has undertaken linguistic study of the original language, including its lexis and syntax.

Jean-Baptiste Michel et al., “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books,” Science 331 (2011): 176–82, DOI: 10.1126/science.1199644, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/331/6014/176.

Jean-Baptiste Michel et al., “Supporting Online Material for ‘Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books’,” (2011):16–17, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/suppl/2010/12/16/science.1199644.DC1/Michel.SOM.revision.2.pdf.

A manageable ECCO search is “the more part of all … ” The Book of Mormon has three of these. If there had been any real increase in original use of “more part” syntax in the early 1700s, we would expect to see some examples of this specific phraseology with all. In ECCO, the nine results from a search performed in June 2018 turned out to yield only three actual hits; but the language dated from much earlier: 1426, 1491, and 1568. So, the 18th-century titles contained 15th- and 16th-century language. This is an important reminder that, in this endeavor, just looking at raw result totals and dates of publication can be completely misleading. This same wording — “the more part of all … ” — turns up 33 times in the 16th century in EEBO1, but not once in the 17th century. This search clearly indicates that “the more part of X” was a phrase characteristic of the 16th century (and earlier).

In June 2018, I also performed a Google Books search of “the more part of X” limited to before the year 1830. A little more than 20 results were returned, but of those that I could read, all of them, besides two false positives, were examples of earlier language, many from legal documents.

Go here to see the 7 thoughts on ““Pitfalls of the Ngram Viewer”” or to comment on it.