[Page 1]Abstract: Jeffrey R. Chadwick has previously called attention to the name ŚRYH (Seraiah/Sariah) as a Hebrew woman’s name in the Jewish community at Elephantine. Paul Y. Hoskisson, however, felt this evidence was not definitive because part of the text was missing and had to be restored. Now a more recently published ostracon from Elephantine, which contains a sure attestation of the name ŚRYH as a woman’s name without the need of restoration, satisfies Hoskisson’s call for more definitive evidence and makes it more likely that the name is correctly restored on the papyrus first noticed by Chadwick. The appearance of the name Seraiah/Sariah as a woman’s name exclusively in the Book of Mormon and at Elephantine is made even more interesting since both communities have their roots in northern Israel, ca. the eighth–seventh centuries BCE.

In 1993, Jeffrey R. Chadwick noted the appearance of the Hebrew name ŚRYH (שריה), typically rendered Seraiah in English, as a woman’s name on an Aramaic papyrus from Elephantine and dated to the fifth century BCE.1 As also pointed out by Chadwick, Nahman Avigad has argued that the Hebrew name ŚRYH(W) should be rendered as Saryah(u), rather than the usual Serayah(u) — which would make the English spelling Sariah instead of Seraiah.2 Thus, according to Chadwick, the attestation [Page 2]of ŚRYH as a Hebrew female name at Elephantine provides strong supporting evidence for the appearance of a Hebrew woman named Sariah in the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi, headnote; 2:5; 5:1, 6; 8:14).3

Paul Y. Hoskisson, however, urged caution about this evidence since the papyrus in question (Cowley-22) has a lacuna requiring restoration of both the final hē (ה) in ŚRYH and the bet- resh (בר) of the Aramaic word brt (ברת), “daughter,” which is the key indication that the individual in question is a woman.4 Thus, Hoskisson cautioned, “restorations cannot provide absolute proof but rather at best a suggestion.”5 He considered it a good sign that “other scholars accept the possible existence of this feminine name in relative temporal proximity to the beginnings of the Book of Mormon,” but Hoskisson ultimately felt “a clear-cut example of the name for a female would be more helpful.”6

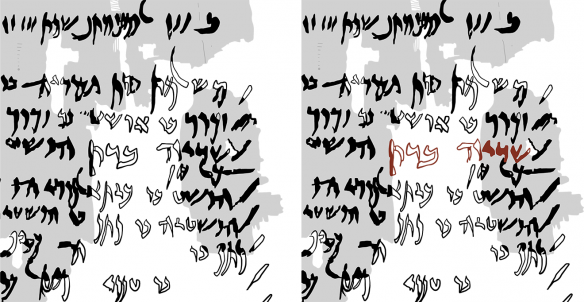

Chadwick argued, however, that “the comparative context of the papyrus leaves little doubt that the reconstruction is accurate,” and it is really “the extant final t” of brt that “assures us that the person was [Page 3]a daughter, not a son.”7 In the most recently published translation and transcription of this papyrus, Bezalel Porten and Ada Yardeni would seem to agree. In their hand-drawing of the Cowley-22 papyrus (see Figure 1),8 they represented the restoration of the final hē (ה) in ŚRYH and the bet-resh (בר) of brt as being “nearly certain.”9

Figure 1. Left: Illustration of Cowley-22, by Jasmin G. Rappleye, based on the drawing by Ada Yardeni in Textbook of Aramaic Documents 3:227 and foldout 32. Right: Same image, with śryh brt, “Seraiah (Sariah) daughter of,” highlighted. The “hollow strokes” used to represent the restored portions indicate that the restorations are considered “nearly certain.”

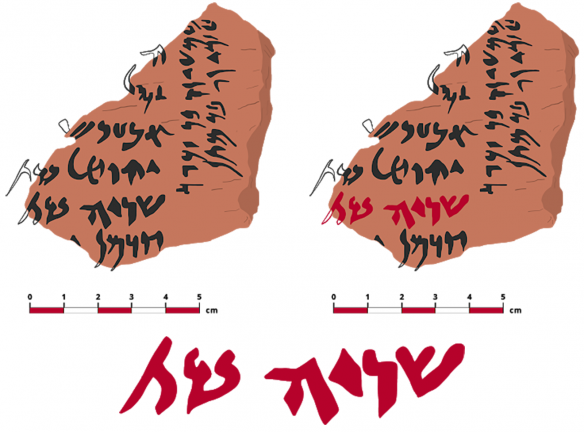

Nonetheless, new evidence that completely satisfies Hoskisson’s call for a more “clear-cut” example has been found. Porten and Yardeni [Page 4]document ŚRYH as a Hebrew feminine name not once, but twice among the Aramaic documents at Elephantine.10 A list of names on an ostracon found there, dated to the second half of the fifth century BCE, includes śryh brt […] ([…]שריה ברת), “Seraiah daughter of […].”11 The name of Seraiah’s (or Sariah’s) parent is broken off, but both “Seraiah” (śryh) and “daughter” (brt) are attested in full,12 thus providing an undeniable example of ŚRYH as a female name (see Figure 2).

This would seem to meet Hoskisson’s demands for more “clear cut” evidence. Furthermore, this clear attestation of ŚRYH as a female name at Elephantine provides reassuring evidence that Cowley-22, which comes from the same period, is indeed restored correctly as “Seraiah, daughter of Hosea.”

In light of Lehi’s ancestors coming from northern Israel (1 Nephi 5:14, 16), ca. 720 bce,13 it is also interesting to note that, according to Karel van der Toorn, the Jewish community at Elephantine ultimately has its roots in northern Israel, ca. 700 bce.14 After surveying the evidence from deity names in the Aramaic texts, van der Toorn concludes, “the entire picture of the religious life at Elephantine and Syene strongly suggest that the historical core of the communities came from Northern Israel.” He [Page 5]further notes “the emigrants from Northern Israel would have entered Egypt by way of Judah” and suspects “some of them stayed in Judah for a significant length of time” before migrating to Egypt sometime in the seventh century bce.15 Therefore, the founders of the Elephantine community were likely contemporaries of Lehi or his parents and were similarly Israelites of northern stock who initially settled in Judah.

These details add to the significance of these two references to women named ŚRYH (Seraiah/Sariah) at Elephantine. In both the Hebrew Bible and the epigraphic evidence from Judah, ŚRYH(W) is only attested as a male’s name.16 While this could simply be due to the limitations of [Page 6]our available data set,17 it is also possible the attestation of ŚRYH as a woman’s name both in the Book of Mormon and at Elephantine and only in these sources, reflects a specifically northern Israelite practice.

Figure 2. Top, left: Illustration of Elephantine Storeroom 2293, by Jasmin G. Rappleye, based on the drawing by Ada Yardeni in Textbook of Aramaic Documents 4:211. Top, right: Same image, with śryh brt, “Seraiah (Sariah) daughter of,” highlighted. Bottom: Detail of śryh brt from the ostracon.

In any case, with the certain reference to a woman named ŚRYH on an ostracon from Elephantine, there can no longer be any doubt that Seraiah/Sariah was a Hebrew woman’s name in the mid-first millennium bce.

[Page 7]Appendix: “Sariah” in Aramaic Texts from Elephantine

The following transcriptions and translations are adapted from Bezalel Porten and Ada Yardeni, Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, 4 vols. (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1986–1999), 3:226–228; 4:211.

Temple Funds Contributors List

Text: Cowley-22 (C3.15), col. 1, lines 1–4

Date: ca. 419/400 BCTranscription

- זנה שמהת חילא יהודיא זי יהב כסף ליהו IIIII לפמנחתף שנת III ב

[II] אלהא לגבר לגבר כסף ש- II משל]מ[ת ברת גמר]י[ה בר מחסיה כסף ש

- II זכור ]בר אוש[ע בר זכור כסף ש

- II שרי]ה בר[ת הושע בר חרמן כסף ש

Translation

- On the 3rd of Phamenoth, year 5. This is (= these are) the names of the Jewish garrison who gave silver to YHW the God each person silver, [2] sh(ekels):

- Meshull[em]eth daughter of Gemar[ia]h son of Maḥseiah: silver, 2 sh.

- Zaccur [son of Ose]a son of Zaccur: silver, 2 sh.

- Serai[ah daught]er of Hosea son of Ḥarman: silver, 2 sh.

Storeroom Names List

Text: Elephantine Storeroom 2293 (D9.14), concave lines 1–5

Date: ca. 450–400 BCTranscription

- […]ה

- [… ח]יסל

- […]אבערש

- [… ת]יהוטל בר

- […]שריה ברת

Translation

- H[…]

- Isla[ḥ …]

- Abioresh[…]

- Jehotal daugh[ter of…]

- Seraiah daughter of[ …]

Editor’s Note: Book of Mormon Central (https://bookofmormoncentral.org/) has just published a blog post and video that are directly related to this article. See them at VIDEO: New Archaeological Evidence for Sariah as a Hebrew Woman’s Name .

Go here to see the 17 thoughts on ““Revisiting “Sariah” at Elephantine”” or to comment on it.