Abstract: The Book of Abraham is replete with temple themes, although not all of them are readily obvious from a surface reading of the text. Temple themes in the book include Abraham seeking to become a high priest, the interplay between theophany and covenant, and Abraham building altars and dedicating sacred space as he sojourns into Canaan. In addition to these, the dramatic opening episode of the Book of Abraham unfolds in a cultic or ritual setting. This paper explores these and other temple elements in the Book of Abraham and discusses how they heighten appreciation for the text’s narrative and teachings, as well as how they ground the text in an ancient context.

[Editor’s Note: This article is an updated and edited version of a paper presented on November 5, 2022, at The Temple on Mount Zion: The Sixth Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference. A slightly different version of this article will appear in the formal published proceedings of the conference, currently in preparation.]

The hermeneutical tradition of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints bears unmistakable witness to a sustained interest in reading scripture through the perspective of the temple. The Book of Mormon and the Book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price have received this interpretive treatment, with a variety of authors offering useful approaches that discern clear temple themes in Latter-day Saint scriptural texts.1 That Joseph Smith’s scriptural translations as well as [Page 212]his revelatory outpouring directly influenced the form and content of the temple endowment ceremony as experienced by Latter-day Saints cannot be doubted. For this reason, the Latter-day Saint canon will continue to be explored for meaningful themes and elements that tie into both ancient and modern temples.

Besides the Book of Mormon and the Book of Moses, which have commanded the attention of many Latter-day Saint interpreters, the Book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price is also replete with temple themes. This book, however, has received comparatively minimal analysis as a temple text. With a few exceptions,2 Latter-day Saints have typically neglected the Book of Abraham in their discussion of temple texts. This is unfortunate, since, as Terryl Givens rightly observed, “the Book of Abraham that [Joseph] Smith produced was a small text, but it was seminal in the development of his mature theological enterprise.”3 This, [Page 213]Givens recognizes, includes the development of Joseph Smith’s temple theology, or his “grand theological project” involving the ordinances of the temple that was “the summit, the culmination, of his entire work of Restoration.”4 This paper seeks to provide a few examples of how the Book of Abraham can be read as a temple text, or otherwise how the temple and temple themes feature in the text.

What is a “Temple Text?”

Before we proceed any further, a simple working definition of “temple text” is in order. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, whose contributions to Latter-day Saint temple theology remain indispensable, has provided an effective definition of this category. Drawing on the work of scholars John W. Welch and Margaret Barker, Bradshaw defines “temple theology” as a branch of theology that concerns itself with encountering God or the divine through the signs, symbols, patterns, and ritual instructions of the temple. A temple text, then, is a text that is infused — narratively, thematically, and even structurally — with the presence of the temple and temple-related patterns, while temple themes are those elements in the text that show a conceptual linkage with the temple.5 Extending this definition, a temple text is a text that captures themes, motifs, teachings, or allusions to the temple; a text that grounds its narrative and cosmology in the temple or in sacred space; and a text that interplays with temple ritual (and vice versa); and a text that thematically incorporates the structures and purposes of esoteric ritual that is performed in the temple or other sacred space.

My approach to the Book of Abraham as a temple text in this study highlights two aspects of what makes this book such. The first is how the temple or the idea of sacred space features in the text. As we shall see, temple elements are depicted throughout the story told in the pages of the Book of Abraham, where at key moments these elements are embedded or otherwise feature prominently. The second aspect is how the text in its canonical form interplays with the modern Latter-day Saint temple endowment; or otherwise, how modern Latter-day Saint readers of the Book of Abraham might bring their temple experience and knowledge with them into their engagement with the text.

[Page 214]“According to the Appointment of God”:

Abraham the High Priest

The Book of Abraham opens in the first-person narrative voice of the eponymous biblical patriarch. “In the land of the Chaldeans, at the residence of my fathers, I, Abraham, saw that it was needful for me to obtain another place of residence” (Abraham 1:1). From there Abraham goes on to frame his record by giving a short but important glimpse into his motives and intentions. “Finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me,” he writes, “I sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same” (v. 2). Avowing that he was already “a follower of righteousness,” and one who possessed “great knowledge,” the patriarch goes on to specify that through his lifelong endeavor to follow God he became “a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers” (v. 2). This priesthood, we are told, was “conferred upon [Abraham] from the fathers”; that is, it was a patriarchal priesthood that was previously held by Adam and other primeval prophets (v. 3; cf. Moses 5:4–12). “I sought for mine appointment unto the Priesthood according to the appointment of God,” Abraham further specifies (v. 4). The theme of Abraham’s priesthood legitimacy is a prominent leitmotif that runs throughout the text,6 and readers again encounter this narrative element later in the book (Abraham 1:18, 31; 2:9, 11). The overall point is clear: Abraham can count himself as belonging legitimately to the patriarchal priesthood of his righteous forebearers, in stark contrast to pretenders like Pharaoh (Abraham 1:26–27).

Abraham’s opening frame, wherein he provides his readers with a list of the outstanding attributes and roles he enjoyed (Abraham 1:1–2), finds intriguing parallel with the self-aggrandizing recitations encountered in Middle Kingdom tomb (auto)biographies. These texts “were often limited to an accumulation of clichés that describe an ideal character and the norms of conduct” reflected in the life of the subject. “Sometimes,” however, like in the case of Abraham, “when its author considered the story of his life and career to be edifying and satisfying, an autobiography became a personal history. Such cases are providential for the historian, who often finds detailed information in them.”7 One [Page 215]need only casually review Lichtheim’s convenient assemblage to spot the similarities in how Abraham frames the outset of his autobiography with how his contemporaries from the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties do the same.8 Indeed, no less than the celebrated Twelfth Dynasty tale of Sinuhe, which opens with the eponymous hero cataloging his achievements and high rank, strikes a familiar chord with the opening of Abraham’s account, even if it is widely regarded by Egyptologists to be fictional (see Table 1).9

But what do these opening lines from Abraham’s record have to do with the temple? In fact, the patriarch’s mention of his “appointment unto the Priesthood” and his status as a “High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers” at once casts his life’s mission and his record in a temple context. By its very definition, priesthood as conceptualized in the ancient Near East involved the performance of cultic and related duties in the temple. “In almost the earliest written documents from Mesopotamia are found lists of the titles of officials, including various classes of priests. Some of these are administrative functionaries of the temple bureaucracy and others are religious specialists dealing with particular areas of the cult. Later records make it clear that a complex hierarchy of clergy was attached to temples, ranging from ‘high priests’ or ‘high priestesses’ down to courtyard sweepers.”10 Although Latter-day Saints today typically define priesthood in terms of the power and authority to act for God,11 this is not primarily how the Book of Abraham envisions such. The text does speak of Abraham’s “right” to the [Page 216]priesthood (e.g., Abraham 1:1–2, 31), but priesthood itself is imagined more as an “order” (v. 26) and “ministry” (Abraham 2:9) into which people enter (Abraham 2:11) rather than a power that people wield.

Table 1. Comparing the beginning of Abraham to the tale of Sinuhe.

| Abraham 1:1–2 | Sinuhe (R1–R5)12 |

|---|---|

| (1) In the land of the Chaldeans, at the residence of my fathers, I, Abraham, saw that it was needful for me to obtain another place of residence; (2) And, finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same; having been myself a follower of righteousness, desiring also to be one who possessed great knowledge, and to be a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and to be a father of many nations, a prince of peace, and desiring to receive instructions, and to keep the commandments of God, I became a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers. | (1) The member of the elite, the governor, the dignitary, the administrator of the Sovereign in the land of the Asiatics; (2) a true acquaintance of the king, whom he loves, the follower, Sinuhe, who says: “I am a follower (3) who follows his lord, a servant of the royal chambers and of the elite lady, great of blessing; (4) the wife of the king Senwosret in United of Places; the daughter of the king Amenemhat, in (5) Exalted of Perfections, Neferu, lady of honor.” |

How might this understanding of priesthood in the context of the temple affect our reading of the Book of Abraham? “Priestly service [in ancient Egypt] was prestigious, since the practitioner of cultic duties was filling an essentially royal role, acting as a liaison between humanity and the gods.”13 What’s more, “temple reliefs portray the king as the sole practitioner of all divine cults, the quintessential high priest of every god’s temple. Although the king presumably performed cultic activities on special occasions at major temples, a hierarchy of local priests was responsible for performing the daily cultural rituals in temples throughout Egypt.”14 This understanding casts Abraham’s [Page 217]“appointment” as a “High Priest” in a new and significant light, as his text can now be read as the patriarch’s self-affirmation of his rightful status as God’s emissary on earth and as a refutation of Pharaoh’s attempt to “fain claim” to “the right of Priesthood” (Abraham 1:27). Abraham’s depiction of his pre-mortal election as a “ruler” nicely complements this rejection of Pharaoh’s claim to priesthood authority, thereby reinforcing and highlighting the rhetorical craft the patriarch put into his account.15 In addition, this understanding amplifies the significance of Jehovah’s covenant with Abraham as described in Abraham 2:6–11 by recasting the blessings of the covenant as specifically temple blessings. Abraham’s role as the intermediary and bearer of this covenant between Jehovah and the nations of the earth can, with this reading, be understood in priestly terms, a point which is made explicit at Abraham 2:11 and further clarified by modern revelation, which affirms that men and women actualize the promised blessings of the Abrahamic covenant by entering into the restored temple priesthood and the new and everlasting covenant (cf. Doctrine and Covenants 131:1–4; 132:1–25, 29–32).16

“That Order Established by the Fathers”:

Pharaoh’s Counterfeit Temple Priesthood

Inextricably linked to the Book of Abraham’s depiction of Abraham as a rightful high priest is the book’s depiction of Pharaoh, Abraham’s rival, as a pretender whose priesthood is counterfeit. In this regard the primeval history or Urgeschichte recounted at Abraham 1:21–28 can be read as a foil to Abraham’s own mainline narrative that describes his journey into the priesthood and his covenant with Jehovah. According to the Book of Abraham, “the first government of Egypt was established by Pharaoh, the eldest son of Egyptus, the daughter of Ham, and it was after the manner of the government of Ham, which was patriarchal” (Abraham 1:25). This Ham was the son of Noah who sired the Egyptians (Genesis 10:6–14) and who, through means not entirely clear, incurred a curse upon his posterity Canaan (Genesis 9:18–29). The Book of Abraham[Page 218] expands upon this enigmatic episode by saying that the curse pertained “to the Priesthood,” so that despite being “a righteous man” who “established his kingdom and judged his people wisely and justly all his days,” Pharaoh nevertheless “could not have the right of Priesthood,” notwithstanding his attempt to claim it through Noahic succession (Abraham 1:26–27).

Exegetes have long grappled with this pericope, which is frustratingly sparse on detail.17 One interpretation, however, can be immediately ruled out, which is that Pharaoh’s curse that disqualified him from the priesthood was black skin. Nowhere does the text of the Book of Abraham support this reading, despite the arguments of misguided Latter-day Saints who uphold old, threadbare interpretive assumptions on the one hand, and those who wish to dismiss the Book of Abraham as nothing more than Joseph Smith’s racist speculation on the other.18 The simple fact is that “the Book of Abraham does not discuss race” as conceptualized today in terms of skin color “and curses no one with slavery,”19 no matter how much people might insist otherwise.20

[Page 219]So while we may not be able to say what precisely the curse of Ham (and Pharaoh) is, we can with some confidence say what it isn’t. But this leaves us still wondering what any of this has to do with the temple. The answer lies in verse 26, which indicates that Pharaoh sought “earnestly to imitate that order established by the fathers in the first generations, in the days of the first patriarchal reign” (emphasis added). Recalling the ancient understanding of “priesthood,” which is evoked in the next verse, this “order” that Pharaoh meant to imitate can be understood to be the temple priesthood that extended back to Adam. Pharaoh’s attempt to establish an ersatz priesthood that rivaled Abraham’s was illegitimate not because of his skin pigmentation, on which the Book of Abraham is silent, but simply by virtue of his belonging to the wrong patriarchal lineage.21 On this point the text is explicit, informing us without even the slightest hint of the melanin content of his skin that “Pharaoh [was] of that lineage by which he could not have the right of Priesthood, notwithstanding the Pharaohs would fain claim it from Noah, through Ham” (v. 27). Abraham, by contrast, could rightly claim his authority by virtue of being a descendant of Shem, Noah’s firstborn (Genesis 6:10; 10:21–32; 11:10–32), which was confirmed by “the records of the fathers, [Page 220]even the patriarchs, concerning the right of Priesthood” that God had preserved with the patriarch (vv. 28, 31).22

In short, in the Book of Abraham “there is no exclusive equation between Ham and Pharaoh, or between Ham and the Egyptians, or between the Egyptians and the blacks, or between any of the above and any particular curse. What was denied was recognition of patriarchal right to the priesthood made by a claim of matriarchal succession” (cf. Abraham 1:23, 25).23 The old racist reading of the Book of Abraham can be safely disregarded and a new reading substituted that situates the text in a temple setting: because of this priesthood denial by virtue of improper lineage, Pharaoh had to make do by instituting a counterfeit temple order and priesthood that was only a poor imitation of what Abraham rightfully inherited from his primeval ancestors.24

“The Altar Which Stood by the Hill”:

The Ritual Landscape of the Book of Abraham

Among the unique and important details about the life of the patriarch provided by the Book of Abraham are the references to the geographical fixtures of his homeland Ur. The first chapter of the text explains how Abraham’s idolatrous kinsfolk in Ur had established a syncretic cult that venerated both Northwest Semitic and Egyptian deities and which practiced human sacrifice “after the manner of the Egyptians” (Abraham 1:6–11).25 Embedded in this description at verses 10–11 is the comment [Page 221]that this cult was operative “by the hill called Potiphar’s Hill, at the head of the plain of Olishem,”26 where it gave “thank-offering[s]” in the form of execrative victims upon an altar.27

One of the first scholars to recognize the significance of this passage was Hugh Nibley, who as early as 1969 observed that the description of Potiphar’s Hill being a site of ritual sacrifice qualified the location as a cult site or ritual complex.28 These ancient cult centers, writes a more recent authority, “were the prime location and focus of ritual activity. Temples and shrines were not constructed in isolation, but existed as part of what may be termed a ritual landscape, where ritualized movement within individual buildings, temple complexes, and the city as a whole shaped their function and meaning.”29 Pilgrimages to these ritual complexes are well-attested, as also is the offering of sacrifices.30 From its description [Page 222]of ritualized activity by a dedicated priesthood in the service of a select group of deities to its mention of sacred architecture at the site, in every appreciable aspect the portrayal of the activity going on at Potiphar’s Hill in the Book of Abraham qualifies the location as a cult center.31 This added context to the inaugural narrative of the Book of Abraham affects our reading of the text in two primary ways. First, it provides “local color” to the historical and geographical setting of the Book of Abraham — the text’s mise en scène, as Nibley and Rhodes rightly recognize.32 Second, it throws Abraham into a sacred, ritual landscape and his narrative into a temple context wherein the patriarch is not just narrating his escape from the clutches of his murderous kinsfolk in Ur, but also their profane ritual practices and sites.

This second point is reinforced when we consider Abraham’s near sacrifice being next to a hill or mountain. “In ancient civilizations from Egypt to India and beyond,” writes Richard J. Clifford in his landmark study, “the mountain can be a center of fertility, the primeval hillock of creation, the meeting place of the gods, the dwelling place of the high god, the meeting place of heaven and earth, the monument effectively upholding the order of creation, the place where god meets man, a place of theophany.”33 As already recognized and discussed with insightful clarity by Nibley, with its depiction of Potiphar’s Hill the Book of Abraham marks the location of the ritual sacrifice of the patriarch as the sacred Urhügel, “the first land to emerge from the great waters and the place where the sun first rose on the day of creation” in the ancient Egyptian [Page 223]cosmic imagination.34 That the temple was and is conceptualized as “the architectural embodiment of the cosmic mountain” needs no additional elaboration. So commonplace is this notion “that it has become a cliché within Near Eastern scholarship. The theme is extremely common in ancient Near Eastern texts.”35 What we thus encounter in Abraham 1 is the narration of a ritualized struggle for cultic legitimacy between Abraham and Jehovah on the one hand and Pharaoh and his array of false deities on the other; a cosmic battle for nothing less than total supremacy over both the divine and human realms.36

“Behold, My Name is Jehovah”:

Theophany, Name, and Covenant

Twice in the Book of Abraham the patriarch receives a revelation of God’s true name, Jehovah, in connection with theophany and covenant.37 In both instances the revelation comes at a moment of trial and in a ritual setting that is accompanied by gestures involving the hand. The first occurred when the Lord intervened to rescue Abraham from being sacrificed by his idolatrous kinsfolk. “And as they lifted up their hands upon me,” the patriarch writes,

that they might offer me up and take away my life, behold, I lifted up my voice unto the Lord my God, and the Lord hearkened and heard, and he filled me with the vision of the Almighty, and the angel of his presence stood by me, and immediately unloosed my bands; And his voice was unto me: Abraham, Abraham, behold, my name is Jehovah, and I have [Page 224]heard thee, and have come down to deliver thee, and to take thee away from thy father’s house, and from all thy kinsfolk, into a strange land which thou knowest not of (Abraham 1:15–16; cf. Facsimile 1, Figs. 1–3).

At this crucial juncture in the narrative (the climax to the text’s opening pericope), the “angel of [the Lord’s] presence” — referring perhaps to the Lord himself acting in his capacity as a divine deliverer — in a “vision of the Almighty” declared his true name to Abraham.38 What immediately follows this revelation is also striking from a temple context and carries with it unmistakable covenant connotations. “Behold,” the Lord told the patriarch, “I will lead thee by my hand, and I will take thee, to put upon thee my name, even the Priesthood of thy father, and my power shall be over thee. As it was with Noah so shall it be with thee; but through thy ministry my name shall be known in the earth forever, for I am thy God” (vv. 18–19). This great theophany that Abraham experienced — wherein he learned the Lord’s true name and received a commission to take that name to all nations, thus extending and democratizing the blessings of the covenant — includes elements that hearken to the temple, including the imagery of the handclasp as a token of recognition,39 the reception of a new (divine) name,40 and another invocation of priesthood.

[Page 225]The second occasion where the Lord revealed his name to Abraham was just before his flight into Canaan during a covenant ceremony involving himself and his nephew Lot. After the death of his brother Haran due to famine in the land of Ur and the backsliding of his father Terah (Abraham 2:1–5), Abraham writes how he and Lot “prayed unto the Lord” (v. 6). In this ritual setting “the Lord [again] appeared unto [Abraham]” in theophany and renewed his covenant with him established in the previous chapter. As John Gee has shown, the covenant pattern or form of Abraham 2:6–11 finds comfortable parallel with covenant or treaty patterns known from Bronze Age sources.41 What is significant for our purposes is the content of that covenant, which again features temple elements. In verse 8, after once again declaring his name as Jehovah, the Lord informed Abraham that his “hand shall be over [him]” so that he would become “a great nation” and a “blessing” through “this ministry and Priesthood” (v. 9). The recipients of this blessing would also receive the patriarch’s name as a token of their own entry into the covenant: “And I will bless them through thy name; for as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as their father” (v. 10). The culmination of these priesthood blessings would be the blessing of “all the families of the earth” with “the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal” (v. 11).

A synoptic view of Jehovah’s declarations at Abraham 1:15–19 and Abraham 2:6–11 reveals a multiplicity of common thematic elements in the two speeches, reinforcing the narrative connectedness of these two passages and their shared covenant context (see Table 2).

[Page 226]Table 2. A comparison of thematic elements common between Abraham 1:15–19 and Abraham 2:6–11.

| Abraham 1:15–19 | Abraham 2:6–11 |

|---|---|

| (15) And as they lifted up their hands upon me, that they might offer me up and take away my life, behold, I lifted up my voice unto the Lord my God, and the Lord hearkened and heard, and he filled me with the vision of the Almighty, and the angel of his presence stood by me, and immediately unloosed my bands;

(16) And his voice was unto me: Abraham, Abraham, behold, my name is Jehovah, and I have heard thee, and have come down to deliver thee, and to take thee away from thy father’s house, and from all thy kinsfolk, into a strange land which thou knowest not of; (17) And this because they have turned their hearts away from me, to worship the god of Elkenah, and the god of Libnah, and the god of Mahmackrah, and the god of Korash, and the god of Pharaoh, king of Egypt; therefore I have come down to visit them, and to destroy him who hath lifted up his hand against thee, Abraham, my son, to take away thy life.42 (18) Behold, I will lead thee by my hand, and I will take thee, to put upon thee my name, even the Priesthood of thy father, and my power shall be over thee. (19) As it was with Noah so shall it be with thee; but through thy ministry my name shall be known in the earth forever, for I am thy God. |

(6) But I, Abraham, and Lot, my brother’s son, prayed unto the Lord, and the Lord appeared unto me, and said unto me: Arise, and take Lot with thee; for I have purposed to take thee away out of Haran, and to make of thee a minister to bear my name in a strange land which I will give unto thy seed after thee for an everlasting possession, when they hearken to my voice.

(7) For I am the Lord thy God; I dwell in heaven; the earth is my footstool; I stretch my hand over the sea, and it obeys my voice; I cause the wind and the fire to be my chariot; I say to the mountains — Depart hence — and behold, they are taken away by a whirlwind, in an instant, suddenly. (8) My name is Jehovah, and I know the end from the beginning; therefore my hand shall be over thee. (9) And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee above measure, and make thy name great among all nations, and thou shalt be a blessing unto thy seed after thee, that in their hands they shall bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations; (10) And I will bless them through thy name; for as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as their father; (11) And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse them that curse thee; and in thee (that is, in thy Priesthood) and in thy seed (that is, thy Priesthood), for I give unto thee a promise that this right shall continue in thee, and in thy seed after thee (that is to say, the literal seed, or the seed of the body) shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal. |

[Page 227]The emphasis seen in these two passages is that of a conceptual interplay between theophany, name, and covenant accompanied by the ritual gesture of giving and receiving the hand. Not only does God lead Abraham by the hand and extend his hand over the patriarch as a ritual gesture (Abraham 1:18; 2:8), but also the imagery of the outstretched hand is evoked to demonstrate God’s dominion over the cosmos (Abraham 2:7), and the hands of Abraham’s seed are said to “bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations” (v. 9). Later in another theophany and night vision God both stretches out his hand to display the cosmos and puts his hand upon Abraham’s eyes to grant the patriarch power to see “those things which [God’s] hands had made” (Abraham 3:11–14). Indeed, even Abraham’s enemies are said to lift up their hand(s) against the patriarch (Abraham 1:7, 15, 17) in an inversion of the covenant imagery just encountered.43 This repeated depiction of the hand as being involved in fluid, dynamic gestures in a variety of contexts — including not just as a literary motif to express a sense of power and action but also explicitly in the context of theophany and covenant — is significant for our reading of the Book of Abraham as a temple text;44 especially in light of the ancient ritual settings in which giving and receiving the hand or placing offerings in the hand(s) plays an important role.45

“I, Abraham, Built an Altar”:

Abraham’s Dedication of the Land of Canaan

The Book of Abraham narrates how the patriarch built altars as he traveled from Haran into the land of Canaan. The text describes two such altars: one built in the land of Jershon (Abraham 2:17) and a second in the land of Canaan near Bethel (v. 20). A third altar is implied at Shechem but is not overtly mentioned; instead, there the patriarch is said to have [Page 228]“offered sacrifice” and to have “called on the Lord devoutly” (v. 18).46 This first instance of Abraham building an altar in the Book of Abraham finds no parallel in the biblical account of Abraham’s wanderings, while the second does (cf. Genesis 12:7–8). Contained in the biblical record is mention of Abraham building altars at additional locations, including explicitly at Shechem (Genesis 12:4), Hebron (Genesis 13:18) and Moriah (Genesis 22:9).

This detail of Abraham building altars as he settled the land of Canaan recasts the narrative in a new temple light. For one thing, the Book of Abraham, building on but also going noticeably beyond what seems to be depicted in Genesis, explicitly frames the patriarch’s building activity in a ritual context. Each time in the Book of Abraham when the patriarch builds an altar — first in Jershon, then implicitly at Shechem, and finally near Bethel — there immediately follows a ritual performance. At Jershon Abraham “made an offering unto the Lord, and prayed that the famine might be turned away” (Abraham 2:17); at Shechem he “offered sacrifice” and “called on the Lord devoutly” (v. 18); and finally at Bethel he “called again upon the name of the Lord” (v. 20). What’s more, at Shechem Abraham experienced a theophany where the Lord appeared to the patriarch and made a prophetic announcement that his seed would inherit the land (v. 19; cf. Genesis 12:6–8). The Book of Abraham thus clearly depicts Abraham’s altars as places of both ritual action (prayer and sacrifice) and theophany.47

The cumulative narrative effect of this, as Matthew L. Bowen has recognized, is that the account of Abraham’s wanderings in Canaan can be easily couched in a temple context. As he writes, “Substantial parts of Genesis 12–22 [and Abraham 2] illustrate how Abraham ‘templifies’ the Promised Land — its re-creation as sacred space — by Abraham’s building altars at Shechem, Mamre/Hebron, Bethel, and Moriah.”48 That Abraham’s altar-building in Canaan plays on temple imagery cannot be doubted. The ritual actions connected to each site are clear enough in the text, and the obvious meaning of the name Bethel (“House of El/God”) [Page 229]further hints at why Abraham may have chosen that site specifically to feature a newly dedicated altar to Jehovah. It was, after all, “the site of an important Canaanite sanctuary to the god El, head of the pantheon.”49 What better way for Abraham to undermine his idolatrous Canaanite neighbors than to repurpose an already existing shrine? So likewise, the altar at Shechem (but not the one at Jershon50) was built to cleanse the “idolatrous nation” of Canaan and its land from ritual pollution (v. 18). The outcome at Shechem is the same as at Bethel: Abraham “ignores the prior pagan sanctity of the place and builds an altar to his own God, thus endowing the site with a new religious history.”51 Having himself nearly been sacrificed on an altar at Potiphar’s Hill (Abraham 1:8–12), Abraham turns the tables on his idolatrous foes and abolishes their profane ritual practices by strategically placing altars around and in the promised land of Canaan, thereby (re)creating and dedicating the land into new sacred space for an ascendent Jehovah to claim for himself and his covenant people.52

“To Be Had in the Holy Temple of God”:

Facsimile 2 and the Temple

A word on Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham seems appropriate to our present undertaking, especially in light of the explanations given to figures 3, 7, and 8–11 by Joseph Smith. I shall keep my observations brief, since fuller treatments of how Facsimile 2 — the hypocephalus of Sheshonq — relates to the temple have already been provided.53 Suffice it to say for now that here we encounter a textbook example of [Page 230]the reciprocal relationship shared between scriptural text and temple ritual, since the canonical explanations to these figures both inform and are themselves informed by the Latter-day Saint temple experience. As important and interesting as the ancient Egyptian understanding of these figures are and how that may converge with Joseph Smith’s explanations to the facsimile54 — something I shall touch on briefly in this discussion — our primary concern here is to explore a few of the ways in which the Prophet, as an inspired syncretist and gifted seer, reappropriated this ancient Egyptian iconography to interplay with and otherwise provide graphic representation for both the revealed text of the Book of Abraham and its temple themes and for the modern Latter-day Saint temple liturgy.55

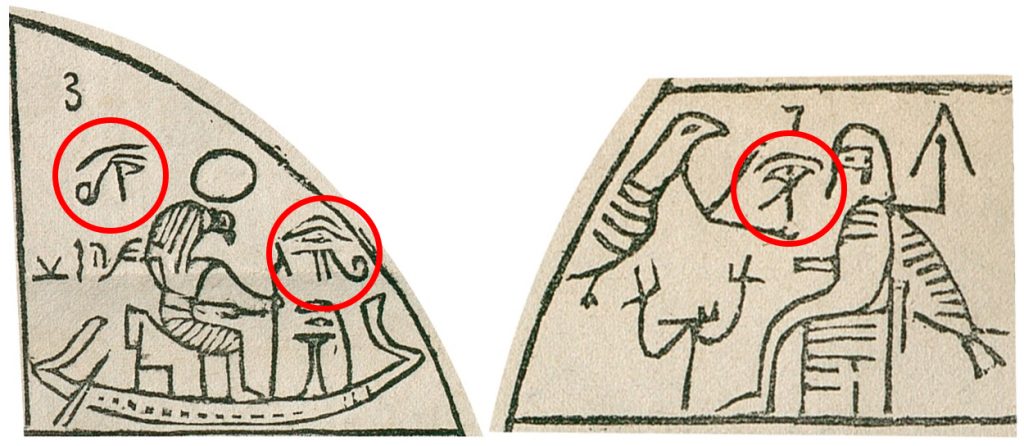

Figure 3 of Facsimile 2 Joseph Smith identified as “God, sitting upon his throne, clothed with power and authority; with a crown of eternal light upon his head; representing, also, the grand Key words of the Holy Priesthood, as revealed to Adam in the Garden of Eden, as also to Seth, Noah, Melchisedek, Abraham and all to whom the Priesthood was revealed.”56 A similar interpretation is given to Figure 7, which is said to be “God sitting upon his throne, revealing, through the heavens, the grand Key words of the Priesthood; as, also, the sign of the Holy Ghost unto Abraham, in the form of a dove.”57 The main operative temple element in both of these interpretations is that God is revealing[Page 231] the keywords of the priesthood. This seems to reflect Joseph Smith’s interpretation or understanding of the seated deity in the proximity of the wedjat (wDAt)-eye in both of these figures.

Figure 1. Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham, figures 3 and 7.58

The wedjat-eyes have been circled in red in both figures.

What might we say about the wedjat-eye that could illuminate Joseph Smith’s interpretation as it pertains to the keywords of the temple?59 First, it might be helpful to know the meaning of the word. In Egyptian, wDA means “hale, uninjured,” and also “well-being,”60 or otherwise “wohlbehalten, unverletzt, unversehrt sein.”61 The word can describe the health or wholeness of the physical body, the soul, or even an individual’s moral character.62 In the Ptolemaic period the word meant “whole or complete” and also “perfect,” and appears in ritual settings where the ib (“heart”) is said to be wDA when the words of the ritual are “spoken exactly” (that is, properly executed).63 In Coptic, true to its Egyptian roots, the word ⲟⲩϫⲁⲓ̈ came to mean “healthy, whole” and, significantly [Page 232]from a temple perspective, “salvation, saved” in the Christian theological sense.64 In the colophon to the Discourse on Abbaton, to name just one of several possible examples, we read of the monk who secured ⲡⲟⲩϫⲁⲓ ⲛⲧⲉϥⲯⲩⲭⲏ (“the salvation of his soul”) for writing and donating the book to the monastery of St. Mercurius in Tbo.65

Beyond its etymology, we can also say something about how the wDAt-eye functioned in Egyptian religion. In its Egyptian context the wDAt-eye was imagined as the “whole” or “sound” eye of the god Horus used in the process of revivifying his father, the god Osiris, and so it held a pronounced apotropaic function. In this regard the eye appropriately symbolized the divine restoration and renewal of the body.66 But the wDAt-eye was more than this. It “could represent almost any aspect of the divine order,” observes Geraldine Pinch, “including kingship and the offerings made to the gods and the dead.”67 It also appears in temple contexts. In Ptolemaic temple inscriptions the term is connected with “saving and protecting the body, or being saved in the temple.”68 The phrase di wDA (“giving wDA”) is used in one Demotic creation text “as something the creator god does to the gods while eternally rejuvenating them, a usage reflected in prayers for mortal individuals,” and it appears in the temple graffiti of petitioners requesting blessings.69 Joseph Smith’s syncretistic recontextualization of the iconography of the wDAt-eye for a Latter-day Saint temple setting is thus entirely appropriate and finds solid grounding from both an ancient Egyptian and an ancient Christian perspective. (What’s good for Coptic Christians is good for Latter-day Saint Christians.) With this understanding, therefore, Latter-day Saints may better appreciate how the figure of the wDAt-eye in Facsimile 2 relates to their own expectation for eternal life and resurrection in God’s [Page 233]presence obtained through the keywords of the priesthood as revealed in the temple liturgy.70

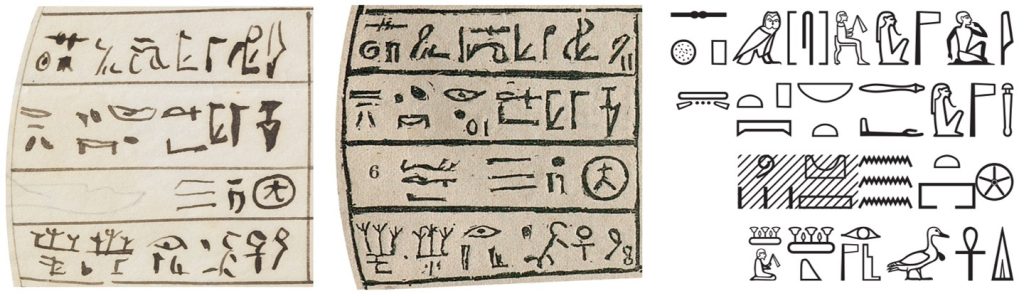

Figures 8–11 of Facsimile 2 Joseph Smith left untranslated, commenting instead that these figures contain “writings that cannot be revealed unto the world” because they are “to be had in the Holy Temple of God.”71 The hieroglyphs that appear in both the manuscript and published versions of Facsimile 2 appear legible enough for us to secure a fairly reliable reading.72

>Figure 2. Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham, figures 8–10.73

Translations of these figures have, accordingly, been offered by Nibley and Rhodes,74 Mekis,75 and most recently Gee,76 with a substandard presentation of the text offered by Ritner.77 There is broad agreement in [Page 234]the translation of these figures, but problematic transcriptions of the hieroglyphs in both the unpublished and published versions of Facsimile 2 give rise to some disagreements, as noted in my translation (see Table 3).

Table 3. Translation of Figures 8-11 of Facsimile 2..

| Original | Translation |

|---|---|

| i nTr Sp(s) m sp | O noble78 god at the first |

| Tp(y) nTr aA nb{t} pt tA | time79 — great god, lord of heaven, earth, |

| dwAt mw [Dw.w] | the underworld, the waters, [and the mountains]80 — |

| di (?) anx bA Wsir 5Sq | may the soul81 of Osiris-Sheshonq82 live! |

Although it may not be obvious at first glance how this relates to the temple, a closer look at the underlying context of this brief inscription and attested parallels reveals something significant. For starters, the ordering of the epithets attributed to the unnamed deity in these lines, [Page 235]most likely the god Amun,83 finds near-verbatim attestation on the pylon gates of both the Amun and Khonsu temples at Karnak.84 The reference to the “first time” (sp tpy; “first occasion,” “first instance,” etc.), is also noteworthy for understanding this inscription as having a temple context, since “frequent are the instances in temple inscriptions in which the historical temple is equated with the st n sp tpy, the Seat of the First Occasion.”85 The phrase was used to describe the Luxor Temple, for example, “first and foremost a creation site and as such [a site that] had a primary role to play in the grand drama of the cyclical regeneration of Amun-Re himself. The god’s rejuvenation was achieved through his return to the very place, even the exact moment, of creation at Luxor; and the triumph over chaos represented by the annual rebirth of the kingship ensured Amun’s own re-creation.”86 So too was it used to designate the “Holy of Holies” of the temple (st Dsrt nt sp tpy; “the sacred place of the first time”).87 The conceptual link between the “first time” of creation and the temple is clear from the ancient Egyptian perspective.

Then there is the benediction of the concluding line: “may the soul of Osiris-Sheshonq live!” It is not difficult to suggest the appropriateness of this invocation for a Latter-day Saint temple context. “A common theme of all Egyptian funerary literature is the resurrection of the dead and their glorification and deification in the afterlife, which is certainly a [Page 236]central element of our own temple ceremony.”88 By reconsidering this line from the perspective of the modern Latter-day Saint temple, we begin to see both the logic behind Joseph Smith’s explanation of these figures in Facsimile 2 as well as how the text may be brought to bear on temple ritual and vice versa. This may also explain why Joseph Smith may have intended to display the Egyptian papyri and the published translation of the Book of Abraham in the Nauvoo temple upon its completion.89 With this methodology a symbiotic relationship between text and temple begins to manifest, so that the Latter-day Saint participant in the temple informs and is informed by these lines in the facsimile. Barring the Latter-day Saints from partaking in this universal habit of religious syncretism as it pertains to their ritual performances in the temple, or somehow insisting that such is illegitimate, is nothing short of special pleading.

Conclusion

In this treatment I have shown how the Book of Abraham can be profitably read as a temple text, or how themes and narrative elements might be identified in the text that amplify its relevance to the Latter-day Saint temple experience. Each of the points discussed in this paper [Page 237]can rightly be more fully explored, and I welcome additional study to that end. Suffice it to say for now that this reading both helps ground the Book of Abraham in the ancient world from whence it derives and provides readers with new insights that may inform their encounter with the book as sacred scripture. If nothing else, it should, I hope, encourage readers not to abandon the text because of controversies related to its translation or production. While shallow or perfunctory readings of the Book of Abraham will, regrettably, remain all too common among those who obstinately refuse Joseph Smith the courtesy of taking him even somewhat seriously and on his own terms — be that out of either commitment to ideological priors or just good old-fashioned anti-Mormon spite — that should not stop us from digging deeper into this inexhaustible text that has unmistakable and important ties to God’s holy temple.

Go here to see the one thought on ““Temple Themes in the Book of Abraham”” or to comment on it.