Abstract: The accounts of the Anti-Christ, Korihor, and of Alma’s mission to the Zoramites raise a variety of apparently unanswered questions. These involve Korihor’s origins, the reason for the similarity of his beliefs to those of the Zoramites, and why he switched so quickly from an atheistic attack to an agnostic plea. Another intriguing question is whether it was actually the devil himself who taught him what to say and sent him on a mission to the land of Zarahemla — or was it a surrogate of the devil or a human “devil” such as, perhaps, Zoram? Final questions are how Korihor ended up in Antionum, why the Zoramites would kill a disabled beggar, and why nobody seemed to have mourned his violent death or possibly unrighteous execution. There are several hints from the text that suggest possible answers to these intriguing questions. Some are supported by viewing the text from a parallelistic or chiastic perspective.

Two of the most gripping stories within the Book of Mormon are first, the account of Korihor and second, Alma’s mission to the Zoramites. These stories have been discussed in many forums, and many authors have supplied commentary on them. However, there remain at least seven significant questions in these accounts — “holes,” if you will. John Welch has called at least some of these lacunae or gaps, “omissions.”1

While answers to these questions cannot currently be proven definitively, the text offers several hints that, like an accumulation of circumstantial evidence in a legal case, can be amassed to provide speculative but credible answers. Some of this circumstantial evidence is new, coming from the relatively recent discovery of underlying parallelistic structures within the Book of Mormon text. John Welch expressed this idea when he wrote: “The design and depth of the [Page 50]Book of Mormon often comes to light only when the book is studied with chiastic and other ancient literary principles in mind.”2 Such parallelistic considerations seem particularly helpful in the case of Korihor and of the Zoramites, as I will attempt to demonstrate.

This article will consider how important themes are presented: 1) in the current verse and chapter format, 2) by parallelistic structures (usually chiasms), and 3) in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. The latter point is important since the modern chapter and verse divisions were not revealed by inspiration to Joseph Smith and were not a part of the first printing. They were provided by Orson Pratt and not published until 1879.3 Because the Saints were generally not aware of the importance of Hebraic parallelisms in scripture, and certainly not aware of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, Pratt inadvertently severed several underlying parallelistic structures. Two of those unfortunate instances occur in the story of Korihor, and one of those turns out to be critical to his connection with the Zoramites, as I will show later in this paper. The questions I will attempt to address in this article include the following:

- Where did Korihor come from, and was he a former Nephite?

- How similar were the beliefs of Korihor to those of the Zoramites?

- Why did Korihor suddenly switch from an atheistic attack to an agnostic plea?

- Was it in fact the devil, Satan himself, who appeared to Korihor?

- How did Korihor end up in Antionum among the Zoramites?

- Was the Zoramite murder of a disabled beggar an execution?

- Why did no one, including God’s prophet, mourn Korihor’s violent murder?

1. Where Did Korihor Come from and Was He a Former Nephite?

It is assumed that readers are familiar with the story of Korihor in Alma 30, which begins after a period of intense war with the Lamanites. The Nephites were enjoying a brief time of peace and rejuvenation characterized by strict observance of the “ordinances of God, according to the law of Moses; for they were taught to keep the law of Moses until it should be fulfilled.”4 The peace was suddenly interrupted by a stranger with an agenda to preach. By stressing the peace of this time, the abridger of these records, Mormon, sets up a foil against which the disruption and chaos that are about to arrive are dramatically contrasted. The [Page 51]stranger was Korihor, the Anti-Christ (Alma 30:6, 12).5 Although his disruption was intellectual and doctrinal rather than military, it was just as destructive as any war. Worse, it threatened eternal consequences for those led astray.

The text describes how Korihor came from obscurity into the land of Zarahemla. Where did he come from? Was he a Nephite or had he once been a Nephite? Such questions are among the major “omissions” to which John Welch refers.6

Let me start with Korihor’s name. Names that ended with consonants often implied a Jaredite or non-Nephite association,7 and the related name “Corihor” is found prominently in the Jaredite record (see Ether 7:3–15; 13:17; 14:27–28). That name and other Jaredite names could have persisted among Jaredite survivors or related non-Nephites who fled to safety when the final civil war of the Jaredites destroyed that civilization, as Hugh Nibley has suggested.8 Alternatively, such names could have been adopted by some to show rejection of the Nephite tradition. Korihor’s name would appear to have stamped him as an outsider. Was that his true birth name, or could he have assumed a Jaredite-sounding name for symbolic purposes — specifically to be stamped as an outsider? It is possible he assumed the name since Korihor, if a Nephite by origin, would have had access to information from the Jaredite records. The story of the Jaredites would have been part of Nephite popular culture and teachings since the Jaredite records had been translated by Mosiah and read to an attentive public audience only 18 years previously (Mosiah 28:17–18). It is worth noting that, chronologically, the first occurrence of the name Nehor, in those records, was the location of a Jaredite battle involving a man of “many evils” named, strikingly enough, Corihor (Ether 7:4, 9, 13). Also striking is that this Corihor had a son named Noah (Ether 7:14). If Korihor had been raised a Nephite, he would have known of Alma’s previous experience with the antichrist Nehor (Alma 1:2–16) and that the life of Alma’s father had been threatened by a king named Noah (Mosiah 18:33). What better name could Korihor have picked to match his mission of an antichrist-rejection of Nephite beliefs and an in-your- face preaching against the teachings of the high priest Alma?

If Korihor was a Nephite, he was certainly an apostate one. Ludlow makes this obvious point when he writes: “The fact that Korihor was brought before Alma would seem to indicate that Korihor was or had been a member of the church.”9 In addition, Korihor used the wording, “I always knew,” in his recanting, which could suggest a life raised in the Church and another connection with the Zoramites, who were all bitter [Page 52]Nephite dissenters.10 As the title of this paper implies, there are grounds for proposing that Korihor was, in fact, one of those apostate Nephites — a Zoramite.11

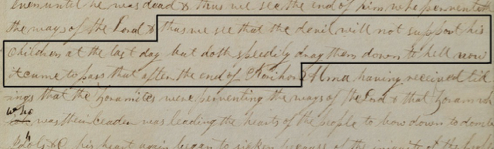

We cannot, of course, prove that Korihor was a Zoramite by origin, but the idea of their association is reinforced by the fact, mentioned earlier, that the two accounts — the story of Korihor (Alma 30) and the beginning of the mission to the Zoramites (Alma 31) — occur next to each other in the modern Book of Mormon and occur in the same chapter (Chapter XVI) in the original 1830 edition. In fact, the last word of Alma 30 and the first one of Alma 31 occur on the same line of the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon with no punctuation separating them (see Figure 1).12

Figure 1. Printer’s manuscript showing position of the original text.

A reasonable answer to question one, “Where did Korihor come from and was he a former Nephite?,” may be that he did, indeed, come from among the Zoramites in Antionum. (This is based on the limited evidence presented so far. More evidence is forthcoming below.) If Korihor did come from Antionum, he, like all Zoramites, would have thus once been numbered among the people of Nephi because the Zoramites were actually Nephites. The text explicitly states that “the Zoramites were dissenters from the Nephites; therefore they had had the word of God preached unto them. But they had fallen into great errors” (Alma 31:8–9; see also Alma 30:59 and 31:2). It is telling that Alma still considered the Zoramites to be “among his people” (Alma 31:2). It also appears probable that Korihor was a Nephite for three additional reasons. First, he spoke their language and spoke it very well; it was almost certainly his native tongue. Second, he was intimately acquainted with Nephite culture and religious beliefs. Third, at one point Alma, in talking to Korihor, labels the Nephites as “all these thy brethren” (30:44).

[Page 53]2. How Similar Were the Beliefs of Korihor to Those of the Zoramites?

If Antionum was Korihor’s home and he was a Zoramite, one would logically expect there to be a considerable similarity between Korihor’s theology and that of Zoram. That is, in fact, what the text reveals. What is known about Korihor’s doctrinal ideas is based on his colorful exchanges with Giddonah and Alma (Alma 30). What is known about Zoramite beliefs comes from two sources: the Rameumptom prayer (Alma 31:12–23) and what the Zoramite poor told Alma (Alma 32:5, 9, 17). Table 1 compares those beliefs.

Table 1. Comparing the Beliefs of Korihor and the Zormites.

| Beliefs and Teachings | Korihor | Zoramites |

|---|---|---|

| 1. There will be no Christ to come | 30:6, 12–13, 15, 22, 39–40 | 31:16, 30 |

| 2. Foolish belief in Christ yokes/binds people down | 30:13, 23–24, 27–28 | 31:17 |

| 3. People cannot know the future | 30:13, 15, 24, 26 | 31:22 |

| 4. Nephites follow foolish/childish traditions of fathers/prophets | 30:13–16, 22–23, 27–28, 31 | 31:16–17, 22 |

| 5. Statutes/ordinances/performances of Mosaic Law dismissed | 30:23 | 31:9–10 |

| 6. Hearts/heads lifted up in pride | 30:18, 23 | 31:16, 18, 24, 27 |

| 7. Value on individualism and individual prosperity | 30:17–18, 23, 27–28 | 31:13, 24, 28 |

| 8. Sign is needed before believing and to know as a surety | 30:43–49 | 32:17 |

| 9. God could not/will not be known or is just a spirit | 30:15, 28, 48, 53 | 31:15 |

| 10. Unchanging nature/condition of God | 30:28 | 31:15, 17 |

| 11. Priests glut on people’s labor for personal gain — priestcraft | 30:27, 31, 35 | 32:5, 9 |

As noted in Table 1, both Korihor and Zoram were adamant that Christ would not come. Both insisted that the people who harbored the hope of Christ had a yoke around their necks and were bound down to a life of passive servitude based on a hope of some future event. Korihor’s and Zoram’s rejection of Christ was fueled by their shared position that the belief in the coming of a Christ required knowledge of the future. Both Korihor and the Zoramites claimed that no human could know or predict that future. Therefore, the prophets who prophesied of a future Christ were foolish and childish. As it relates to the Mosaic Law, Korihor [Page 54]criticized the “ordinances and performances which are laid down by ancient priests” (30:23). Likewise, the Zoramites would not “observe to keep … statutes, according to the law of Moses. Neither would they observe the performances.” (31:9–10).

The pride of both Korihor and the Zoramites is more complex. Korihor’s own pride caused him to preach with “great swelling words” and to enjoy his success so much that he came to believe his own lies. In addition, he promoted the pride of the people by calling for them to lift up their heads in their wickedness and whoredoms. The Zoramites, in their turn, praised God that they were chosen and elected to be saved while others were elected to hell. Further, they “boast[ed] in their pride” (31:25) of material possessions.

While the emphasis on individualism and individual prosperity is not identically expressed, Korihor’s and the Zoramites’ values appear to be similar. Korihor preached that “every man fared in this life according to the management of the creature [the individual, not the collective and not God]; therefore every man prospered according to his [own] genius, and … [individual] strength” (30:17). This sounds like survival of the fittest. Korihor called for those individuals to lift up their heads with boldness and pridefully enjoy “their rights and privileges” (30:27).

The Zoramites appeared to have also valued the individual, if that is the symbolic meaning of the Rameumptom, which specifically admitted only one person at a time. In addition, the Zoramite priests’ pride-filled and puffed-up “hearts were set upon gold, and … fine goods” (31:24–27) and not on fellow man or serving the social good. As McConkie and Millet point out, “Though salvation is an individual matter, it is of necessity a collective effort. We are saved as we help each other.”13 Rather than helping others, the Zoramite elite seemed concerned with apparel, wealth, pride, and individual aggrandizement.

When Alma pointed out Korihor’s “lying spirit,” Korihor fell back on his core belief that signs create faith — “and then will I be convinced” (30:42–43, 48). Although the Zoramites did not mention signs in their Rameumptom prayer, Alma almost echoed Korihor’s words when he later explained to the Zoramite poor that “there are many who do say: If thou wilt show unto us a sign from heaven, then we shall know of a surety; then we shall believe” (32:17). Since the poor did not deal with others outside their community, the “many” who held that belief would likely have been the Zoramite priests.

Beliefs nine and ten in Table 1 concern the nature of God. Although Korihor appears to have insisted that God did not exist while the [Page 55]Zoramites prayed, if only weekly, to God and to “dumb idols” (31:1), heads and tails usually belong to the same coin. What, at first glance, looks like an opposite is actually a similarity in that both were rejecting God — as the Nephites viewed God. Both Korihor and Zoram rejected the Nephites’ specific concept of a knowable and loving Father with a body of flesh and bone. Korihor claimed that this kind of God was unchangeable in that he “never has been seen or known … never was nor ever will be” (30:28). Korihor was explicitly told that he should preach that God was “an unknown God” (30:53). However, he must have believed in some form of a god, otherwise there would be a logical inconsistency in rejecting one immortal being, God, while accepting the existence of another immortal being, the devil. He may have been rejecting the Nephite view of the nature of God rather than completely rejecting any possibility of a supernatural force, per se.14 On the other side, the Zoramites prayed to a God, similarly unchangeable, saying “thou wast a spirit, and that thou art a spirit, and that thou wilt be a spirit forever” (31:15). Again, this was a very different God than that of the Nephites.

The Zoramites also bowed down to dumb idols (31:1). Since idols are not mentioned again, it is not clear what was meant unless “idol” referred to the Zoramite “spirit god,” who divided the elect from the non-elect. Alma may have meant that the spirit god of the Zoramites was a false illusion (an idol) of the true, corporeal God who is no respecter of persons. Easton’s Bible Dictionary presents different Hebrew terms that are translated as “idol.” All four specifically refer to a false likeness of deity. Those are the Hebrew semel, or likeness; tselem, or shadow; temunah, or similitude; and tsir, or form or shape.15 Smith’s Bible Dictionary defines an idol as “anything used as an object of worship in place of the true God.”16 A third definition from The Oxford Companion to the Bible renders, “An idol is a figure or image worshiped as the representation of a deity.”17 The idea of a mutual rejection of the Nephite God may then suggest a similarity rather than an opposition of beliefs.

The last point listed in Table 1 involves priestcraft. Korihor accused the Nephite leaders of “glutting on” and exploiting the people for gain, which was something he appeared to vehemently reject (30:31). But was Korihor using only the accusation of priestcraft to stir up the people against the Nephite priests or to have a serious accusation to hurl against those priests? That was an obvious weapon to use. Yet, a reasonable question to ask is, would Korihor not have also subjugated the people if he had succeeded in obtaining a power position over them? This stands to reason. The Zoramites actually did practice priestcraft [Page 56]as shown by the fact that the poor built the synagogues but then were prohibited from using them (32:5). This theme of oppression is further shown in Alma 35:8–9. Once the poor left the land of Antionum, the elite Zoramites wanted them back, presumably to exploit them further in order to continue to accumulate riches. So, if Korihor was a Zoramite, he would have been used to seeing the poor subjugated (see Alma 32:5 and 9). Again, an apparent opposite is actually a similarity.

Taken as a whole, the similarity of these eleven beliefs seems to go beyond mere happenstance. Unless Korihor was a Zoramite, the many similarities would seem unlikely to have occurred by coincidence alone. If there had been no association, one would expect a much greater diversity in their teachings. An example of such diversity is the hundreds of Protestant theologies that have sprung out of Martin Luther’s rejection of Roman Catholic orthodoxy in 1517 CE. By contrast, Korihor and Zoram appear to have rejected Nephite teachings on the same points, in many of the same ways, and in the same and often identical language. Hugh Nibley cut to the bottom line and taught: “They have the same philosophy.”18

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland also sees an interrelationship of the two philosophies. He noted that “[Korihor’s] … brand of teaching inevitably had its influence among some of the less faithful who, like the neighboring Zoramites, were already given to ‘perverting the ways of the Lord’ [Alma 31:1].”19 Now, was he saying that Korihor directly influenced the neighboring Zoramites? Or was he merely saying that those “many” who Korihor did initially influence in the land of Zarahemla (Alma 30:18) were like the Zoramites in that both groups, independently, were perverting the ways of the Lord? One detail that supports the former reading (Korihor influencing the Zoramites) is his second comment that the Zoramites were “spared any belief in … ‘foolish traditions’” (the same term used by Korihor in Zarahemla),20 which gave, in Elder Holland’s words, “evidence of Korihor’s legacy emerging here [Antionum].”

I may be misinterpreting Elder Holland’s words because it seems unlikely that Korihor influenced the Zoramites. It is much more likely that it was Zoram who influenced Korihor. If Korihor did have any influence on Zoram and his followers, it could not have happened after Korihor’s encounter with the Nephites in Zarahemla; it could only have occurred prior to his arriving in Zarahemla. After being rendered dumb, he was reduced to a beggar, begging for food door-to-door (possibly in Zarahemla but definitely later in Antionum [Alma 30:58–59]). If he could have influenced anyone by then, the entire point of striking him [Page 57]dumb so that he could not preach would have been lost and the will of the Lord would have been thwarted. It is possible that he influenced the Zoramites prior to arriving in Zarahemla but unlikely since the apparently charismatic leader of the Zoramites was Zoram, not Korihor. Nor could it have been any of Korihor’s followers in Zarahemla later carrying his teachings to the Zoramites. The scriptures explicitly say that “they were all convinced of the wickedness of Korihor; therefore they were all converted again unto the Lord; and this put an end to the iniquity after the manner of Korihor” (30:58, emphasis added). It seems much more likely that Zoram influenced Korihor, even trained him, as I will assert below. In any case, there seems to be a reasonable answer to question two, “How similar were the beliefs of Korihor to those of the Zoramites?” That answer is: remarkably similar. Thus, the parallels in the eleven beliefs further the likelihood that Korihor was, in actuality, a Zoramite.

3. Why Did Korihor Suddenly Switch from an Atheistic Attack to an Agnostic Plea?

It is important to remember that Korihor’s first attempt at preaching to the people, apparently in Zarahemla, was highly successful in that he led “away the hearts of many … women, and also men” (30:18; see also 30:20 and 57). There was nothing that Alma, or anyone else, could do to stop him from preaching against Nephite religious beliefs and practices. Since he was receiving nothing for doing so, this was not priestcraft. Mormon used precious space on the plates to point out that “there was no law against a man’s belief; for it was strictly contrary to the commands of God that there should be a law which should bring men on to unequal grounds. For thus saith the scripture: Choose ye this day, whom ye will serve” (30:7–8; citing Joshua 24:15). Put another way, Korihor had full legal authority to his beliefs, even apparently to preach them, and it was the right of those listening to choose to accept what he had to say or choose to reject it.21 If the point was not clear enough, it was reiterated three verses later when Mormon wrote that “there was no law against a man’s belief” (30:11) and that “the law could have no hold upon him” (30:12).22

Why such emphasis on the law? This will come into play in Alma’s confrontation with Korihor. For the moment, it is enough to realize that Korihor had, as yet, committed no crime. For the moment, his first attempt at preaching to the people was highly successful (30:17). Korihor now had a following. Perhaps riding a crest of confidence and [Page 58]likely flushed with success, he decided to try his luck in the Nephite land of Jershon and preach his doctrine to the recent Lamanite converts of Ammon. That was a mistake. Ten years earlier, the people of Ammon had seen more than a thousand of their brethren suffer death rather than renounce a newly acquired belief in Christ. They would not easily abandon those beliefs based on Korihor’s highly intellectual challenges. In that way, the people of Ammon “were more wise than many of the Nephites” (30:20). Ammon, now the high priest of the church in Jershon, would have none of it. Korihor was bound and “carried out of the land” (30:21).

Korihor then tried his preaching in the land of Gideon. Another mistake. The people of Gideon were also unique in that they were living in a locale named after a revered Nephite hero who had been murdered by another antichrist, Nehor, only 16 years earlier (Alma 1:7–9). They would not easily be swayed by a new Anti-Christ. Consequently, he “did not have much success” (notice he had some success) and was again bound. This time, he was taken before an ecclesiastical leader, Giddonah, and an unnamed legal judge of the law — a law which, the scriptures clearly say, did not apply to Korihor’s beliefs (30:21).

This account of his failures in Jershon and Gideon can be viewed as a parallelistic six-step “extended alternate” (alternating lines in a form such as abcd/abcd) as formatted by Donald Parry.23 It is presented here, not just to clarify Korihor’s experiences in Jershon and Gideon but also to illustrate how the 1879 verse divisions sliced a parallelistic structure in half. The point to notice is that the final element of this alternate (a1–f1) is not a part of verse 20 but occurs in the beginning of verse 21. Significantly, a2 then begins after verse 21 has already started. This means that the current verse division awkwardly splits the extended alternate describing Korihor’s failure in Jershon (a1) and his failure in Gideon (a2). This kind of unfortunate division will become important at the end of Alma 30 and the beginning of Alma 31, where a chapter division will split another parallelism, producing confusion about Alma’s great sorrow and an unnatural and possibly incorrect closure on the story of Korihor. More on that later. Here is the extended alternate:

| a | (30:19) Now this man went over to the land of Jershon also, | |||||

| b | to preach these things among the people of Ammon, who were once the people of the Lamanites. | |||||

| c | (30:20) But behold they were more wise than many of the Nephites; | |||||

| d | for they took him, and bound him, | |||||

| [Page 59]e | and carried him before Ammon, who was a high priest over that people. | |||||

| f | (30:21) And it came to pass that he caused that he should be carried out of the land. | |||||

| a | And he came over into the land of Gideon, | |||||

| b | and began to preach unto them also; | |||||

| c | and here he did not have much success, | |||||

| d | for he was taken and bound | |||||

| e | and carried before the high priest, | |||||

| f | and also the chief judge over the land. | |||||

With no legal recourse against Korihor’s preaching in Gideon, all Giddonah could do was attempt an appeal to reason. However, his logic was immediately counterattacked by Korihor who then accused the priests of oppressing the people for gain — a serious accusation of priestcraft. Shocked at the vitriolic ferocity of the attack, and with no legal recourse, Giddonah “would not make any reply” (30:29). Instead, he referred the problem to a higher authority: the prophet Alma and the chief judge and “governor over all the land.”24 In what are described as “great swelling words” (30:31), Korihor blasphemed again and also attacked the priests and teachers of the church for various beliefs and practices he charged as oppressive.

Some 15 years earlier, Alma had experienced a similar dilemma with Nehor, another antichrist. “Priestcraft … was not against the law, strictly speaking.”25 However, in Nehor’s case, the false preaching could be combined with the murder of Gideon, an old and defenseless cultural hero (Alma 1:12). This created the somewhat complicated verdict of “endeavoring to enforce priestcraft by the sword,”26 and Nehor was executed “according to the law” (Alma 1:13–14). Alma had no such easy fix with Korihor. Under the laws of the judges, he was rendered helpless in dealing with Korihor — at least, using a legal recourse.

The text then describes the suspenseful encounter as Korihor matched wits with Alma, the prophet and head of the church. Korihor had been able to silence Giddonah fairly easily, largely through shock value. With Alma, it would be different. Although Korihor was to find himself outmatched, he did not yet know that. There was initially no sign of him being intimidated by a face-to-face reckoning with the prophet. Perhaps Korihor had interpreted Giddonah’s silence as a capitulation, or perhaps he had been waiting for just such an audience with Alma. Either way, Korihor intensified his allegations.

[Page 60]Alma brilliantly defended himself against the accusations of priestcraft, and then lodged a counter-argument. He began by bearing a simple testimony in a three-step extended alternate, first identified by Donald Parry.27

| a | (30:39) Now Alma said unto him: | ||

| b | Will ye deny again that there is a God, | ||

| c | and also deny the Christ? | ||

| a | For behold, I say unto you, | ||

| b | I know there is a God, | ||

| c | and also that Christ shall come. | ||

Alma then moved from the arena of faith to take up the issue of physical evidence and proof. This will be presented here in chapter and verse format. The chapter and verse format has been sanctioned by the Lord for almost 200 years. It has helped to convert almost 16 million members. In this case, though, a parallelistic view, which I will present later, does provide additional clarity. First, let’s consider the chapter and verse format.

Alma first pointed out that Korihor had no negative evidence: “what evidence have ye that there is no God” (30:40). It is difficult (although not impossible) to prove a negative from an absence of evidence.28 Later, Alma pointed to “the earth, and all things that are upon the face of it, yea, and its motion, yea, and also all the planets which move in their regular form” (30:44) as evidence of the existence of God. While undoubtedly comforting and convincing to those who love the Lord and appreciate the beauties of nature, it is not clear that either of these arguments would convince a skeptic like Korihor of the existence of Deity. Yet, the story of Korihor’s debate with Alma is often taught as if it were Alma’s logic (about the natural world) that brought about the change and stopped Korihor’s attacks. Again, although Alma’s reference to nature undoubtedly slowed Korihor down, it is doubtful that this particular evidence would be enough to convince such an enthusiastic and passionate atheist. Brigham Young University (BYU) scholar Joseph Spencer put this idea even more strongly, calling Alma’s argument “a weak defense.”29 He elaborates further:

Alma offers a positive argument in his defense, but, again, such an argument is unlikely to persuade an atheist or even an agnostic … . A believer naturally and rightly sees God’s hand in the order of the universe, but unbelievers are seldom swayed by this kind of argument. In other words, what Alma [Page 61]offers in response [to Korihor] … is an interesting defense of the faith he [Alma] already has, but it is not a satisfying reason to begin believing. … It thus seems that Alma lacks a fully developed defense when he first confronts Korihor’s skepticism.

Spencer goes on to build an illuminating case that Alma had a “more mature response”30 in Alma 32 after Korihor was dead and again in Alma 36. If he is correct, one may well ask, “Then why did Mormon include Alma’s evidence of nature in the account of Alma 30?” It may be that Mormon included Alma’s logic of the natural world, not so much to suggest that it could influence a hard-core atheist like Korihor but to provide evidence for modern-day readers who would be more open-minded and teachable.

Alma then cites “all things as a testimony” (30:41) and later, “the testimony of … the holy prophets … [and] the scriptures” (30:44). Again, these were likely insufficient to sway Korihor. Alma then asks if Korihor will deny this “proof.” At this point, there is a dramatic and abrupt end to Korihor’s aggression. From that very moment on, Korihor completely changes his tone. He shifts from an incendiary, attacking atheist to a questioning, even pleading, agnostic. Starting in the very next verse (30:43), Korihor retreats to the defensive, imploring: “show me a sign, that I may be convinced” and “show unto me that he hath power, and then will I be convinced.”31

Why the dramatic turn-around? If logic did not stop Korihor, what did? It appears the accusation and charge that Korihor was lying that Alma leveled at him in the previous verse (30:42) upended Korihor. Alma asserted that Korihor had taken on the lying spirit of the devil and put off the Spirit of God. Reading this in the cultural context of the modern world, whether Korihor was lying or not might be considered trivial, even expected. Modern-day examples of prominent figures lying publicly come readily enough to mind. For Alma and Nephihah, though, the fact that Korihor had lied, essentially perjuring himself in court, was neither trivial nor expected. That accusation appears to have struck Korihor to the core. Like a child caught with a hand in the cookie jar, Korihor was caught in a lie while testifying in court and immediately ceased all attacks.

Why? It appears to be because lying in Nephite society had special significance. Although there was no legal punishment for a lack of belief in God or Christ, there was a specific Nephite law against lying. All communities of believers in Christ have considered deception and [Page 62]dishonesty a serious and grievous sin starting from the earliest scripture (see Leviticus 19:11, “Ye shall not steal, neither deal falsely, neither lie”). It is implied in the Ten Commandments (“Thou shalt not bear false witness” [Exodus 20:16]). It continued through to the very end of the Bible in Revelation 21:18 (“All liars, shall have their part in the … second death”). It is likewise true in the modern Church: “Thou shalt not lie; he that lieth and will not repent shall be cast out” (Doctrine & Covenants 42:21).

In Nephite society, however, lying was also considered a punishable crime. In Alma 1:17, Alma pointed out that apostate Nephites “durst not lie, if it were known, for fear of the law, for liars were punished; therefore they pretended to preach according to their belief; and now the law could have no power on any man for his belief.” Korihor could believe and preach anything he wanted, but he “durst not lie … for fear of the law.” Although the Book of Mormon does not give the specific punishment for the crime of lying, it was apparently severe. In any case, this put the possibility of a legal consequence squarely back into play. A cursory reading of the modern verse format sounds as if Korihor’s lying spirit (30:42) was a passing observation — an aside — as it would be in our modern times. For Nephihah and Alma, it was not. They had found their prosecutorial key. Without the legal accusation of lying, perhaps Korihor may have continued his aggressive, atheistic attacks.

Unfortunately for Korihor, he panicked and immediately compounded the crime of lying with the biblical sin of asking for a sign. Such a request is completely contrary to the plan of faith — “a wicked and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign” (Matthew 16:4). Rather, the divine plan is: “ye receive no witness until after the trial of your faith” (Ether 12:6). By asking for a sign, Korihor superseded his legal problem of the crime of lying with the much more serious spiritual problem of sign-seeking.32 At that moment, the ball switched from Nephihah’s legal court to the spiritual purview of Alma. Alma immediately jumped on the sign-seeking, emphatically warning Korihor that “if thou shalt deny again, behold God shall smite thee” (30:47). It appears to have been the combination of the criminal lie, and the insistence on a sign of proof, that brought about Korihor’s downfall. Note that he had been warned multiple times, in unmistakable fashion, that he was tempting God and was about to be struck down.

Despite the warning, Korihor repeated his plea for a sign, and the scriptures provide the dramatic account of the judgment of God in an elegant five-point chiasm.33 Korihor was struck dumb on the spot.34 It [Page 63]is an interesting irony that, in his own youth, Alma had also sought “to destroy the church of God” (Mosiah 27:10). He, too, had become “dumb, that he could not open his mouth” (Mosiah 27:19). The fact that it was now Alma’s mouth that condemned another to be struck dumb seems powerful.35

In psychological terms, Korihor’s reaction to the cursing reflects a noticeable external locus of control or external orientation. Korihor immediately externalized the blame by playing the victim card. He said, in effect, “the devil made me do it,” rather than taking personal responsibility for his own behavior. Korihor had not been forced to accept the devil’s messages; he had done so voluntarily. Satan has no power beyond what humans yield. “Resist the devil,” James 4:7 instructs, “and he will flee from you.” And just as Korihor externalized the blame for his sin, so he continued to play the victim role by seeing the curse as external — it came upon him and needed to be “taken from him” (30:52, 54). He again externalized the responsibility to expiate the sin onto Alma: “he besought that Alma should pray unto God” on his behalf (30:54). It is as if Korihor were saying, “There, I made my quick confession. Now get God to remove the curse!” Since Korihor had failed to exercise the internal control to resist, and thereby had created his own situation, he needed to be the one to extricate himself. Korihor could ask the prophet to intervene just as the modern faithful may ask for various kinds of priesthood blessings, but the responsibility for sincere repentance is on the individual.

The externalization continued with his rationalization that “I have taught his words” (notice “his” words, not “my” words [30:53]). Korihor claimed that he “taught them, even until … I verily believed that they were true; and for this cause I withstood the truth” — in other words, he did not “technically” lie. We have heard such rationalizations from people of influence in our own day. Unfortunately for Korihor, the accusation of lying was confirmed when he confessed, “I always knew that there was a God” (30:52). That was a direct contradiction to his earlier statement that there was no God (30:37–38) and proved the lie. But it was too late. For Korihor, lying became moot now that he was mute.

Earlier, I claimed that a parallelistic formatting would offer an additional perspective. The difficulty with the chapter and verse presentation is that I had to repeatedly say that Alma made this or that point and then later repeated the same points. Why would he do that? Alma clearly:

- [Page 64]started with evidence (30:40)

- moved to his testimony (30:41)

- mentioned denial (30:41)

- then belief (30:41–42)

- accused Korihor of being possessed by a lying spirit and instead, rejecting a “place in him” for the “Spirit of God” (possessed by the Spirit) (30:42).

At that point, Alma had essentially won the day. He had found his prosecutorial key and shocked Korihor into retreating from an attacking atheist to a doubting agnostic asking for a sign. Why did Alma then repeat the sequence in reverse order, which only weakened his case? He repeated:

- possession, this time by the devil who has power over him and carries him about as a destructive “device” or tool (30:42)

- conviction (belief) by a sign (30:43)

- tempting God unless there was a sign (denial) (30:44)

- testimony of brethren (30:44)

- evidence of scriptures, earth, planets (30:44)

This is illogical. In an effective sales strategy, a salesman always stops selling after the client has agreed to the purchase. A successful salesman doesn’t mention other benefits after the deal has been closed. It is simply inexplicable — unless viewed as the downward side of a chiasm. The up and down pattern of a chiasm presents the events in a more understandable and logical way.

Although presenting the material as a chiasm is not essential for answering question 3, “Why did Korihor suddenly switch from an atheistic attack to an agnostic plea?,” the placement of the chiasm provides additional evidence for the importance of the lie. In saying this, I fully understand that finding chiasms that have not previously been identified has become suspect in the Book of Mormon scholarly community — and rightly so. One person’s “intentional” (i.e., real) chiasm could be another person’s “inadvertent” (i.e., false) non-chiasm.36 It has been pointed out numerous times that a repetition of words is not enough to clearly indicate that the original author meant to create a self-contained parallelistic and poetic structural unit.37 For example, Parry has pointed out, “Not every chiasmus is equal in value, some are considered to be marginal, while others consist of strong chiastic elements.”38

[Page 65]The confidence in the chiasticity of any parallelistic structure is strengthened by 1) a strong “anchor” for the chiasm and 2) a climactic apex at the turning point. Well, the climax is there. You simply can’t get a more dramatic climax than the accusation of being possessed with a lying spirit, an accusation that completely turned the table on the Anti-Christ. As John Welch points out, it is at that point that “Korihor probably realized that the weight of evidence was stacking up against him.”39 And the twin anchors also seem solid and clear. Evidence is the foundation for any legal process, and Alma starts the chiasm with the first anchor of Korihor’s total lack of evidence (30:40). He ends the chiasm with the second anchor of his own multiplicity of evidence, especially the beauty and order of nature and the cosmos (30:44). Why else would the evidence be separated by four verses unless they were anchor points?

In my thinking, a strong five-point chiasm, with embedded, extended alternates, seems to jump off the page. This chiasm fully explains Alma’s apparent backtracking. The chiasm is as follows:

| A1 | a | (30:40) And now what evidence have ye | Evidence | ||

| b | that there is no God, | ||||

| b | or that Christ cometh not? | ||||

| a | I say unto you that ye have none, save it be your word only. | ||||

| B1 | a | (30:41) But, behold, I have all things | Testimony | ||

| b | as a testimony that these things are true; | ||||

| a | and ye also have all things | ||||

| b | as a testimony unto you that they are true; | ||||

| C1 | and will ye deny them? | Denial | |||

| D1 | a Believest thou | Belief | |||

| b | that these things are true? | ||||

| a | (30:42) Behold, I know that thou believest, | ||||

| E1 | a | but thou art possessed with a lying spirit, | Possession | ||

| b | and ye have put off the Spirit of God | ||||

| c | that it may have no place in you; | ||||

| [Page 66]E2 | a | but the devil has power over you, | Possession | ||

| b | and he doth carry you about, working devices | ||||

| c | that he may destroy the children of God. | ||||

| D2 | a | (30:43) And now Korihor said unto Alma: If thou wilt show me a sign, | Belief | ||

| b | that I may be convinced | ||||

| c | that there is a God, | ||||

| a | yea, show unto me that he hath power, | ||||

| b | and then will I be convinced | ||||

| c | of the truth of thy words. | ||||

| C2 | a | (30:44) But Alma said unto him: Thou hast had signs enough; | Denial | ||

| b | will ye tempt your God? | ||||

| a | Will ye say, Show unto me a sign, | ||||

| B2 | a | when ye have the testimony | Testimony | ||

| b | of all these thy brethren, | ||||

| b | also all the holy prophets? | ||||

| a | The scriptures are laid before thee, | ||||

| A2 | a | yea, and all things denote there is a God; | Evidence | ||

| b | yea, even the earth, and all things that are upon the face of it, yea, and its motion, | ||||

| b | yea, and also all the planets which move in their regular form | ||||

| a | do witness that there is a Supreme Creator. | ||||

The A1 anchor is comprised of a short, four-element chiasm stating a null hypothesis (you have no evidence that there is no God). That statement of non-evidence is matched with the A2 anchor, which is another short, four-element chiasm citing evidence based on nature and on the orbits of the earth and the planets.40

The B steps move from the concept of physical evidence to the concept of testimony.41 B1 was identified as a simple alternate by Donald Parry.42 In it, Alma declares that both he and Korihor “have all things as a testimony.”43 B2 is a small chiasm that points to the testimonies (verbal and scriptural) by Korihor’s “brethren” and “all the holy prophets.”

The C steps pair Korihor’s denial of the evidence and the testimonies with his denial of signs he has already received and his tempting of God [Page 67]by asking for more signs. Jacob faced this same dilemma over 400 years earlier when he had to deal with the antichrist, Sherem. In Jacob’s words, “What am I that I should tempt God to show unto thee a sign in the thing which thou knowest to be true?” (Jacob 7:14).

In D1, a small chiasm states Alma’s inspired conviction, through discernment, that Korihor really does believe. Alma asks the question, though he already knows the answer. This is paired with an extended alternate in D2, where Korihor asks to be convinced and therefore, ostensibly, to believe.

It is in the all-important apex or climax of any chiasm — in this case, the E steps — that the tide turns.44 Korihor was possessed with a lying spirit that was not of God (E1), and the devil had power over him, carrying him about, because of that possession (E2).

The chiastic analysis, if correct, appears to confirm that it was not the simple argument of orbiting planets and scriptural testimonies that shook Korihor to the core. Instead, it was the accusation and charge of criminally lying to the people and perjury in front of Nephihah, the governor and chief judge, that served as the catalyst for Korihor’s about-turn. This accusation of lying was not merely a passing comment as it may appear in a casual reading. Its centrality and importance in Korihor’s trial, and indeed in his story, may be why Mormon places the charge squarely in the apex of this chiasm, giving it major significance (the E steps).

Given all this evidence, it appears that the answer to question 3, “Why did Korihor suddenly switch from an atheistic attack to an agnostic plea?,” appears to be that he was caught in a criminal lie while testifying in court and not so much that the orbits of the planets proved the existence of God. Lying was a charge that Alma, Nephihah, and Korihor apparently took very seriously — more seriously than the modern reader might expect — serious enough to shock Korihor to the core.

4. Was it in Fact the Devil, Satan Himself, Who Appeared to Korihor?

The possibility of Korihor’s origins among the Zoramites and the similarity of beliefs between Korihor and Zoram suggest that Korihor may have been teaching Zoramite doctrine. Hugh Nibley put forward a similar idea calling Korihor “the ideological spokesman for the Zoramites and Amalickiahites.”45 But that still leaves the question of exactly who taught him what he should say. The Sunday school answer is that Satan whispers the same doubts and lies to all antichrists. But that is [Page 68]not true; all antichrists are not cut from the same mold. John Welch has pointed out, “Nephite dissenters have less in common than one might assume.”46 He later adds that they “differ widely and significantly in their theology, religion, and political agendas.”47

Besides, Korihor did not claim that Satan “whispered” anything. He stated, unequivocally, that the devil “appeared unto me” and “taught me that which I should say” (30:53). Perhaps we should take that at face value. However, there are hints that this may have had a metaphorical meaning. First, the exact quote is: “The devil hath deceived me; for he appeared unto me in the form of an angel” (30:53, emphasis added). “Form of an angel” seems an important qualifier. It suggests that Satan did not appear in his own form. This suggestion is supported by Korihor’s relative lack of importance or status; he was not a great prophet like Moses. Moses did receive a personal visit from Satan, a supernatural being who Moses could actually see and talk to (Moses 1:12–14). Korihor comes across like a malcontent with a silvery tongue and an axe to grind. In other words, was Korihor of sufficient status for Satan to actually appear to him, presumably on several occasions in order to teach him? Note that the devil potentially has millions of targets. The angel who guided Nephi through his great eschatological vision was clear when he proclaimed, “Behold there are save two churches only; the one is the church of the Lamb of God, and the other is the church of the devil” (1 Nephi 14:10). The Book of Mormon and the book of Revelation point out that the church of the devil is massive — the angel in 1 Nephi called it a “great church” while John describes it as a “great whore that sitteth upon many waters” (Revelation 17:1). It would seem an extremely rare occasion for Satan himself to appear and instruct a mortal, just as it is an extremely rare occasion for Christ himself to appear among us. God and Christ generally work through a “divine investiture of authority.” Angels and prophets are usually those who speak for, and on behalf of, God.48 An example of this comes from the account of a heavenly being who appeared to John the Revelator and spoke in the voice of, and as if he were, Jesus Christ. When John “fell down to worship before the feet of the angel” who appeared to him, the personage quickly said, “See thou do it not: for I am thy fellowservant, and of thy brethren the prophets and of them which keep the sayings of this book” (Revelation 22: 8–9).

We know very little about either how Satan works or how his “church of the devil” operates. However, it is possible that there might be a satanic investiture of authority. “The devil also has ‘angels’ or messengers.”49 [Page 69]Could the phrase, “in the form of an angel,” suggest that a human angel acted as a surrogate for Satan and his devilish ideas?

Supporting the idea that the words “in the form of” suggest a representation of the original is the baptism of Christ. When he was baptized, all four Gospels, First Nephi, and the Doctrine and Covenants all report that the Spirit descended “like a dove” (Mark 1:10; Luke 3:22; John 1:32) or “in the form of a dove” (1 Nephi 11:27; 2 Nephi 31:8; Doctrine & Covenants 93:15). In an 1843 meeting in the Nauvoo Temple, Joseph Smith explained that “The Holy Ghost is a personage, and is in the form of a personage. It does not confine itself to the form of the dove.”50 Similarly, Facsimile 1 in the Pearl of Great Price interprets the drawing of a bird or dove as an “Angel of the Lord”51 but that angel was not a bird. As a simplistic analogy, when a friend of mine was passing through the city where my grandchildren live, he was kind enough to deliver a gift to them from me. In a sense, I “appeared” to my grandchildren “in the form of” my friend.

As far as that goes, why does the record even contain the phrase, “in the form of an angel”? If the devil appeared to Korihor, the devil appeared to Korihor. Given limited metal plates and difficulty inscribing, why add the words that the appearance was really in some qualified form — the form of an angel? This qualifying phrasing may suggest that something else was happening. Several pieces of evidence, that I will enumerate one by one, offer an idea of what might have been going on.

First, if Satan did appear symbolically in the form or likeness of a mortal man, the most likely candidate for this surrogate angel, or messenger, would be Zoram. Was it Zoram who taught Korihor “what I should say” (30:53)? Granted, Zoram was not a supernatural messenger. However, both Heavenly Father and Satan primarily use natural means to accomplish their ends. Both can, and do, use mortals to function in the capacity of “angels,” a word that comes from the Greek angello, meaning a messenger.52 For example, the Lord used the mortal Assyrians and the Egyptians to chasten Israel. He also uses righteous mortal men and women, even teenage missionaries, to teach and convert. People today are rarely broadsided by a visit from a Korihor or a Zoram, much less a visit from Satan himself. Rather, the damage comes from elements of doubt sown by someone in the guise of (form of) an insidious pseudo-friend or teacher. The object to be feared is usually one that is all too familiar.

Second, tutoring by another human would be a natural process. An actual appearance by Satan would be a supernatural process. This presents [Page 70]a major inconsistency of logic. It would mean that a supernatural being (the devil) was telling Korihor that there were no supernatural beings (God or Christ). Now, it is possible that Korihor was again denying the Nephite concept of God or that Korihor was thinking polytheistically and denying the existence of one particular deity while accepting the existence of other supernatural beings. However, absent those possible mindsets, the inconsistency would likely have occurred to someone as intelligent as Korihor.

Third, there may also be another piece of evidence in the agenda that was given to Korihor. According to Elder James E. Faust, the goals of the devil include “seeking glory, power, and dominion by force.”53 Moses 4:4 warns that Satan wishes “to deceive and to blind men, and to lead them captive at his will.” Elder Dallin H. Oaks teaches that “Satan is still trying to take away our free agency by persuading us to voluntarily surrender our will to his.”54 None of these quite match the agenda that Korihor was given. In his own words, Korihor was told, “Go and reclaim this people” (Alma 30:53). That sounds very different. While Satan could “claim” people into his Great and Abominable Church, Satan could not “reclaim” people who were not previously his. Zoram, on the other hand, was once a Nephite and had led a separation away from the church. Having experienced success in Antionum, he may have wanted to reintegrate the people of Zarahemla and surrounding locales and bring them under his theological, financial, and political control. While reintegrating is not exactly the same as reclaiming, this agenda seems to fit Zoram more closely than it fits the agenda of the devil.

Fourth, the possibility that Zoram acted as a surrogate or angel of the devil gives added meaning to Alma 30:60: “thus we see that the devil will not support his children at the last day.” Not only did the real devil not protect Korihor at the end but if the angel of the devil was really Zoram or his followers, they did not protect a now disabled Korihor either — they trampled him to death.55

The fifth and final piece of evidence is much more complicated. The two verses that close Alma 30 and the two verses that open Alma 31 could be viewed using a parallelistic lens. They appear to form what seems to me to be one united chiasm that has not yet been articulated in the literature. I again respect that different scholars view chiasmus in different ways and can disagree on the chiasticity or accuracy of a chiastic candidate. I present the chiasm here as merely a supporting, though intriguing, additional piece of evidence for the speculation that [Page 71]Zoram may have acted as a surrogate for Satan and taught Korihor his doctrine.

At the very end of Alma 30, Mormon inserts an editorial summary, or colophon,56 of the moral lesson of Korihor. He moralized: “And thus we see the end of him who perverteth the ways of the Lord; and thus we see that the devil will not support his children at the last day but doth speedily drag them down to hell” (30:60). Powerful! That colophon definitely sounds like the end of the story, and with that colophon, the door appears to close on Korihor. Chapter 31 contains the story of the Zoramites, which seems to be a separate account of an unrelated incident. But not so fast.

In the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon there was no chapter division to force an end to Korihor’s story after Mormon’s colophon. This is significant. Instead of a chapter division, the complete Korihor account and the complete Zoramite story were in one integrated chapter called Alma XVI. In the current edition of the Book of Mormon (1981 print; 2013 internet), they are separated by chapters. But what if the story carries on after the colophon? Nothing says it couldn’t, and in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, the text simply continued with the next paragraph of the same chapter.

In my parallelistic analysis there appears to be a significant chiasm here, which conflates these two chapters by combining the introduction to the Zoramites (30:59), the murder of Korihor (30:60), and Mormon’s colophon (30:60) with the tidings of the Zoramite perversions (31:1) and Alma’s heartsickness and sorrow (31:2). This chiasm, if intentional, demonstrates that the 1830 inclusion of the two stories into a single chapter correctly relates Korihor to the Zoramites. It was undoubtedly Mormon’s colophon that fueled Orson Pratt’s decision to end an already long chapter after Alma 30:60. However, the severing of the chiasm and the chapter division obscured a possible further connection between Korihor and the Zoramites. If this is correct, it seems highly significant. This is the chiasm I propose:

| A1 | a | (30:59) And it came to pass that as he went forth among the people, yea, among a people who had separated themselves from the Nephites | |||

| b | and called themselves Zoramites, | ||||

| b | being led by a man whose name was Zoram — | ||||

| a | and as he went forth amongst them, | ||||

| [Page 72]B1 | behold, he was run upon and trodden down, even until he was dead. | ||||

| C1 | a | (30:60) And thus we see the end of him | |||

| b | who perverteth the ways of the Lord; | ||||

| c | and thus we see that the devil will not support his children at the last day, | ||||

| d | but doth speedily drag them down to hell. | ||||

| C2 | a | (31:1) Now it came to pass that after the end of Korihor, | |||

| b | Alma having received tidings that the Zoramites were perverting the ways of the Lord, | ||||

| c | and that Zoram, who was their leader, | ||||

| d | was leading the hearts of the people to bow down to dumb idols, | ||||

| B2 | a | his heart began to sicken | |||

| b | because of the iniquity of the people. | ||||

| c | (31:2) For it was the cause of great sorrow to Alma | ||||

| b | to know of iniquity among his people; | ||||

| a | therefore his heart was exceedingly sorrowful | ||||

| A2 | because of the separation of the Zoramites from the Nephites. | ||||

In this interrupted chiasm, the two anchor points are the twin references to the highly significant fact that a large group of Nephites had separated themselves from the main body of Nephites. They rejected the culture, language, and religion of the Nephites and became the prideful Zoramites (the A steps). More specifically, A1 pairs with A2 to indicate that the Zoramites had separated from the Nephites under the leadership of “a man whose name was Zoram” (31:1) who was a “very wicked man” (35:8).57 It is not hyperbole to say the separation of the Zoramites from the Nephites represented no less than a civilization-ending threat for the main body of the Nephites.58 It is this separation that serves as the solid anchor points for the chiasm I propose.

The B steps pair the murder of Korihor (B1) with a small chiasm in B2 that describes Alma’s heart being sickened and exceedingly sorrowful because of Zoramite iniquity. What was that iniquity that so disturbed Alma? Certainly, a part of that was the potentially catastrophic separation described in the A steps. While it may be tempting to jump to the conclusion that another part of that sorrow was the doctrinal atrocity of the Zoramite belief system, that cannot be correct; Alma had not yet seen that. That’s why he was later “astonished” when he finally [Page 73]arrived in Antionum (Alma 31:12). However, it is entirely reasonable to assume a whole new source of sorrow — namely, that some of his heart being sickened and sorrowed (B2) was because the Zoramites had just “run upon and trodden” to death a dumb beggar with no regard for the law and no regard for a fellow child of God, no matter how deceived and deceiving he had been.

I will return to these B steps later in the paper. For the sake of question 4, let us focus for now on the C steps of the chiasm. In a review of literature attempting to develop a set of rules for recognizing chiastic structures, Neal Rappleye points to the apex of any chiasm as the climax, crescendo, or most important part of the parallelistic structure.59 In the case of this chiasm, if it is correct, the apex is an extended alternate (the C steps). Notice that the first side of the extended alternate occurs in Alma 30 while the second side of the extended alternate occurs in Alma 31. Strikingly, Orson Pratt’s division of Alma 30 and 31 chops in half this extended alternate. For ease of discussion, I am repeating the apex (the C steps), simplified to their basic elements:

| C1 | a | … the end of him | |||

| b | … perverteth the ways of the Lord; | ||||

| c | … the devil … his children at the last day, | ||||

| d | … drag them down to hell. | ||||

| C2 | a | … the end of Korihor, | |||

| b | … perverting the ways of the Lord, | ||||

| c | … Zoram … their leader, | ||||

| d | … bow down to dumb idols, | ||||

The first half of the extended alternate (C1) describes the “end” of him “who perverteth the ways of the Lord” and that the devil (who had “children” or followers) drags them down to hell. This is paired with the second half of the extended alternate (C2), which describes the “end” of Korihor; that the Zoramites were “perverting the ways of the Lord;” and that Zoram, “their leader” (i.e., he had followers) is leading his people to bow down to (hellish) idols. As supplemental evidence for the idea that Zoram was the surrogate of Satan and was there to teach Korihor what to say, notice that the two small “c” steps of the extended alternates pair the devil with Zoram. In other words: the devil thus may be equated with Zoram. This view is not as extreme as it might initially appear. Zoram is clearly at least a type for the devil in that leading people to worship idols is dragging them down to hell (the small “d” steps).

[Page 74]In answer to question 4, “Was it in fact the devil, Satan himself, who appeared to Korihor?,” I have attempted to present a range of evidence that, when Korihor said the devil appeared “in the form of an angel” (30:53), he may have been referring to Zoram as that angel. It may be that Satan himself did not physically appear to Korihor to teach him what to say; that was left to Zoram. This raises the question of why Korihor didn’t simply name the teacher as Zoram rather than the devil in the form of an angel. One possible answer is that this is a label he used for a man who, in his view, caused his cursing. Another is that Alma (or Mormon) is using this metaphor to more powerfully highlight Zoram’s role and/or his inspiration. A third is that some kind of cultural language is being employed here. In any case, the tentative response to question 4 may be that it was Zoram who taught Korihor what to say. This idea will also be important in answering question 6 as well. But, first, question 5.

5. How did Korihor End Up in Antionum among the Zoramites?

The fifth question asks how Korihor ended up in Antionum, of all places, after he was struck dumb. Why didn’t Alma cast him out into Zarahemla, the capital city, where people would know to still be wary of him? Why not Jershon or Gideon where faith was strong and they could have taught him and perhaps brought him back to some level of repentance? Why not banishment in a far-off location in the north, like Bountiful, where he hadn’t yet established any kind of base? How about sending him to the far south — maybe even the land of Nephi, and let the Lamanites deal with him? Why Antionum?

Alma 30:56–58 declares that after Korihor was “cast out,” he went “from house to house, begging food for his support.” The very next verse says that “as he went forth among the people, yea, among a people who had separated themselves from the Nephites and called themselves Zoramites … he was run upon and trodden down, even until he was dead” (30:59). Whether he started out in Zarahemla or not, he at least ended up in Antionum, and it sounds as though he did that almost immediately. The dates at the bottom of the pages in the Book of Mormon suggest that the entire story of not only Korihor but the mission to the Zoramites all took place in one year, 74 BCE, so he couldn’t have been begging long — perhaps weeks, perhaps months. The point is that he was “cast out” and soon ended up in Antionum, and the question is, why?

There are two possibilities for when the dumb Korihor arrived in Antionum. First, Alma could have simply cast him into the city, which would have been the capital city, Zarahemla. But that would have been [Page 75]among the very people Korihor had tried to corrupt. True, he was now dumb, and his influence was severely limited. Still, he had earlier been successful in “leading away the hearts of many … yea, leading away many women, and also men” (30:18). It was only because the people feared that “the same judgments [being struck dumb] would come unto them” (30:57) and an official proclamation had been “published” by the chief judge, Nephihah, that the people were “converted again unto the Lord” (30:58). It is an unnecessary risk to cast Korihor back out into the very same environment where he had seen such success. And if Alma had, indeed, cast Korihor out into Zarahemla, that begs the questions of why Korihor didn’t stay there, and why and when he eventually wandered to Antionum. Note that Antionum was, according to all scholarly maps, a distance of many days travel from Zarahemla.60 Not only that but according to John Welch, “an ancient person could not easily relocate in another city [because] a severe banishment (or herem) was pronounced publicly, with a ‘warning not to associate with the anathematized.’ According to Josephus, outcasts often died miserable deaths.”61 The only explanation seems to be that Antionum was his home. As a mute (and possibly deaf) beggar, he might have expected to have more success if these were “his people” than by begging among strangers.

The second possibility for when Korihor arrived in Antionum is that Alma cast Korihor immediately and directly into Antionum. Now, it is unlikely that a prophet of God and/or a righteous chief judge would cast out even an antichrist in an angry or vengeful way. Rather, it would have been done in a more thoughtful way. But that begs the question of why Alma would have chosen Antionum as the location for him to be cast out. Why there? There is a modern-day logic that indigent poor should be cared for by the people of their home rather than allowing them to become burdens on the people in a new host location. One example of this comes, centuries later, from Great Britain. Based on English Poor Laws, “Justices issued a removal order if they were satisfied that a person or family needed (or were likely to need) relief but had no right to settlement in the parish. A removal order directed that a person or family be returned to their parish of legal settlement.”62 Parenthetically, I had two direct-line ancestral families who fell on hard times and were exiled from London based on English Laws of Settlement and Removal. The first removal of a direct-line ancestral family to their home parish happened in 1792. The second direct-line family, this one with small children, was escorted out of London in 1818, this time by a police constable. I have copies of both removal documents.

[Page 76]Writing centuries earlier and on another continent, Alma obviously knew nothing about English law. However, it seems likely that one’s place of origin should bear the burden of taking care of their own indigent poor — even among pre-modern societies. The text records that Alma had not yet received tidings about the Zoramites “perverting the ways of the Lord.” He only learned of that “after the end of Korihor” (Alma 31:1). Given that lack of information, the choice of Antionum would have made perfect sense to Alma if it was Korihor’s home. This is not a trivial point. It was just after Korihor was transported to Antionum that Alma received the tidings of corrupt religious practices among the Zoramites and, presumably, that Korihor had been killed by them. Now, I am not a great believer in coincidences, and this would have been a whopper. Although it is not certain, it is a good possibility that the news of the Zoramite corruption, and possibly the news of the murder, were carried back to Alma by the very men who had just transported Korihor to Antionum. The scriptures are clear that Alma did not learn about the corruption in Antionum until “after the end of Korihor,” and in Alma 31, Alma’s heart “began to sicken” (31:1). This sequence places a portion of the Korihor story directly into the beginning of Alma 31 — independently of any proposed chiasm or parallelism. Mormon’s colophon, while appearing to place a final exclamation point on the story of Korihor, turns out to be an editorial parenthesis, not an editorial termination. A significant piece of the story of Korihor appears to continue into Alma 31:1. Further, Alma’s sorrow at the Zoramite iniquity, including his shock at the illicit murder, pushes the story of Korihor into verse 2 and possibly as far as verse 11.

Once this is realized, it makes intuitive sense why the original 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon had the two stories in the same chapter (Chapter XVI) — they may not be unconnected stories, after all. Alma’s sudden awareness of the corruption of the Zoramites and his desire to travel to Antionum himself (with a missionary force) may well be related to the story of Korihor. Strikingly, it may not be a coincidence of timing, as many assume. Alma’s interest in the Zoramites and his awareness of their spiritual corruption and iniquity may have come about as a direct result of Korihor being cast out among them where he was soon murdered. Many people (and I, for one) suspect that most so-called “coincidences” have a deeper story to tell. In any case, the answer to question 5, “How did Korihor end up in Antionum among the Zoramites?,” may be that he had returned, or been sent, to his place of origin with the erroneous [Page 77]expectation that his own people would better support him. Again, and in addition, we see more evidence that Korihor, likely, was a Zoramite.

6. Was the Murder of a Disabled, Helpless Beggar Actually an Execution?

If Korihor returned to Antionum in the hopes that the Zoramites would take care of him, he was sadly and completely mistaken. The scripture is clear that “as he went forth amongst them, behold, he was run upon and trodden down, even until he was dead” (30:59). Could this have been an accident? That doesn’t seem likely. Korihor was not just trampled and he was dead — Korihor was trampled “until he was dead.” Hugh Nibley took the position that it was a murder when he taught his students that Korihor “was run over and put to death by a mob.”63

Consider, also, Mormon’s colophon in the last verse of chapter 30. An accidental death would not demonstrate how the devil fails to support his followers. However, if that death were a brutal murder, it makes it easier to find a lesson of the devil’s abandonment of his own in that violent and volitional end. “It is by the wicked that the wicked are punished” (Mormon 4:5). Korihor’s demise seems a deliberate and brutal murder at the hands (or rather the feet) of the Zoramites — a grievous iniquity. The question becomes, why would a random and disorganized mob murder a disabled and helpless beggar? John Welch supplies one credible answer, writing that Korihor “had been cursed by a god and was therefore a pariah, or one marked with evil spirits,” adding that Korihor’s death “was based on a concern or fear about receiving into the city someone who had been cursed by God.”64

There is another possibility. I have tried to provide logical and scriptural support for the ideas that Korihor came from among the Zoramites, had been taught what to say — possibly by Zoram acting as an angel or surrogate of the devil — and had been given an agenda to “Go and reclaim this people” (30:53). That sounds a lot like being sent, probably by Zoram, on a special mission to towns in the land of Zarahemla.65 If all that is correct, it might logically follow that Korihor was not just an ordinary, isolated Zoramite. Could he have been one of Zoram’s priests? There is obviously no scriptural evidence that Korihor had been a Zoramite priest, but logical reasoning suggests it is possible since the text only emphasizes two classes of Zoramites. There were those who prayed publicly on an elevated platform and the outcast poor.66 Alma 31:20 records that, with the exception of the poor who were excluded from Zoramite society (32:5, 9, and 12), “every man did go forth [Page 78]and offer up these same prayers … [on the] Rameumptom” (31:20–21, emphasis added). Does that mean they were all priests? Hard to say, but even if there was a middle class made up of common residents, Korihor must have been more than just a random citizen. It stands to reason that he had considerable importance in Zoramite society if he had been personally tutored by either the devil himself or an angel of the devil (possibly Zoram) had personally tutored him and sent him on a special mission to “Go and reclaim this people” (Alma 30:53).

If he had, indeed, been sent out on a mission to the land of Zarahemla, it was without question a failed mission. If Korihor was returning from a miserably botched mission, the fact that he was now a dumb (and possibly deaf) beggar would have been a constant reminder of God’s judgment against the teachings of Zoram. That would not have sat well with Zoram and his priests.

To see a failure in a scriptural story is not at all unusual. One could even say that failures in Biblical accounts are commonplace. The Hebrew idiom for “completely failed” is ala batohu. The first part can mean “resulted in” while the second part refers to nothingness, a void. Thus, ala batohu means “an attempt to do or to attain something” resulted in nothing.67 There appears to have been a Hebraic “tradition,” if you will, of extreme consequences for such ala batohu. There are too many failures that occurred among Old Testament figures to list them all, but the following are a few failures prior to Lehi departing Jerusalem.

- The people of Babel failed to bridle their pride and, like Satan, sought to become as God. As a result, their unified language was confounded and “the Lord [did] scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth” (Genesis 11:4–9).

- Esau failed to respect his birthright, selling it for “bread and pottage of lentiles,” and the rights of the eldest son were bestowed upon his younger brother (Genesis 25:29–34).

- Miriam failed to respect the unique position of the prophet, Moses, as the Lord’s mouthpiece, and she was struck with leprosy. The curse was lifted in return for banishment from the camp for seven days (Numbers 12:9–10, 14).

- Moses failed to give God the glory when he struck the rock to produce water. In consequence, he was denied entrance into the promised land (Numbers 20:10–12).

- The high priest, Eli, failed to raise his sons in righteousness and control their corruption (1 Samuel 2:12, 22). As a result, [Page 79]both of his sons died on the same day, he was replaced as the high priest, and he was denied posterity (2:31–36).

- King David failed to curb his lust, slept with Bathsheba, and arranged for Uriah to be killed to attempt to hide his indiscretion. His failure led to the Lord saying he would “raise up evil against thee out of thine own house” (2 Samuel 12:11); the public loss of his wives (12:11-12); the death of his first child with Bathsheba (12:18); and, perhaps worst of all, “therefore he hath fallen from his exaltation” (D&C 132:39).

If Korihor returned to Zoram and had to report an utterly failed mission, a void, it is logical to expect an extreme response. In this scenario, murder by a random mob may be the wrong word. It is not beyond reason that he could have been summarily executed, not just murdered, possibly under orders of their leader, Zoram. Supporting this conjecture is the choice of the tools of the killing. Where stoning to death was an Old Testament response to blasphemy,68 trampling was an Old Testament sign of utter disrespect and worthlessness. The Hebrew expressions, trampled or trodden, are usually translated as “loath, tread (down, under [foot]), be polluted.”69 Among the many examples that could be offered are:

- “Trodden with your feet … fouled with your feet” (Ezekiel 34:19)

- “Shame shall cover her … now shall she be trodden down as the mire of the streets” (Micah 7:10)

- “Neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet” (Matthew 7:6)

- “If the salt have lost his savour … it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men” (Matthew 5:13)

Nephi provided his own definition for this expression when he explained, “Yea, even the very God of Israel do men trample under their feet; I say, trample under their feet but I would speak in other words — they set him at naught, and hearken not to the voice of his counsels” (1 Nephi 19:7). Is it another coincidence that Korihor happened to die by trampling, or could Zoram and his priests have chosen a manner of death that conveyed a Hebraic message of contempt? Again, one possible answer to question 6, “Was the Zoramite murder of a disabled, helpless beggar actually an execution?,” could be in the affirmative. It is possible [Page 80]that the once proud Korihor, now reduced to a mute begging for his food, may have been executed by his own people, the Zoramites, for a failed mission to the Nephites.

7. Why Did No One, Including God’s Prophet, Mourn Korihor’s Violent Murder?

The verse format of Korihor’s story offers absolutely no reaction to this illicit and grievous murder. Why not? The chapter and verse text leaves the reader with the impression that Alma, God’s righteous prophet, simply ignored it. Alma’s sorrow in Alma 31 is attributed to only two causes:

- the iniquity and perversions of the Zoramites (31:1), and

- the separation of the Zoramites from the Nephites (31:2).