[Page 89]Abstract: This contribution focuses on the earliest and one of the most significant chapters of the Book of Moses: Moses 1, sometimes called the “Visions of Moses.” Kent Jackson summarizes the sources available relating to the production of this chapter, illuminating obscure corners of its often misunderstood background with his extensive knowledge of the history, manuscripts, and significance of the Joseph Smith Translation.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See Kent P. Jackson, “The Visions of Moses and Joseph Smith’s Bible Translation,” in “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017), 161–70. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/to-seek-the-law-of-the-lord-essays-in-honor-of-john-w-welch-2/.]

Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible covers the entire Bible but not with equal emphasis. The most extensive and dramatic additions to the text are found in Genesis and were revealed in the first months of the translation. Because of the lack of conclusive historical sources for much of the summer and fall of 1830, there are unanswered questions about the earliest stages of the translation work. In this paper I do not argue a thesis but simply describe and discuss the evidence. I identify [Page 90]some of the questions about the early translation and attempt to show what can and cannot be said in response to those questions.1

In June 1830, two months after the Church of Christ was organized, Joseph Smith dictated the first pages. They are recorded on a manuscript that archivists call Old Testament Manuscript 1 because it is the earliest of the extant manuscripts of the translation.2 The first nine pages of this document are in the hand of Oliver Cowdery. At the top of page 1 is a heading that was likely supplied by Cowdery: “A Revelation given to Joseph the Revelator June 1830.” The text itself starts with the title, “The words of God which he gave <spake> unto Moses at a time when Moses was caught up into an exceeding high Mountain. …” Over much of its history, this revelation, found on pages 1–3 of the manuscript, has been called the Visions of Moses. It was first published in 1843 in the Church’s periodical Times and Seasons.3 It was then published in 1851 in the Millennial Star and included in the British Mission pamphlet, The Pearl of Great Price. In 1880 it was canonized along with the rest of that collection. It is now chapter 1 of the Book of Moses.

The Visions and Genesis

The Visions of Moses has no Bible counterpart. It is not an expansion of any biblical verse or a revision of any biblical passage. Much of its content deals with themes hardly mentioned in the Old and New Testaments. It is uniquely Latter-day Saint in its teachings and is one of the most distinctive and significant texts of the Restoration. But the nature of the document leads to this question: Is it part of the New Translation of the Bible? The scribal title, “A Revelation given to Joseph the Revelator June 1830,” may suggest that Joseph Smith was not aware of its relationship [Page 91]to the Bible initially, though that relationship became apparent in due time. The Prophet and his associates treated the revelation as something different from most of the other revelations he had received. To the best of our knowledge, it was always associated with the Genesis revision that follows it on the manuscript. It was never included in the manuscript collections of the early revelations, either in Revelation Book 1 or in the later Revelation Book 2. Nor was it included among the divine communications printed in the Book of Commandments in 1833 or the Doctrine and Covenants in 1835. It is very different from those texts, which are mostly messages to the Church at large or to individuals by name, dealing with the establishment of the Church, its mission, and its institutions. In them, God is the speaker; it is his voice that addresses the recipients.4

The Visions of Moses, in contrast, tells a story. It is an account in the words of an unidentified narrator. God is not the speaker. When God speaks, he is being quoted, just as the other characters are quoted in the narration. In the account, God appears to Moses and teaches him about his creations—“worlds without number” that fill the universe. Moses asks, “Tell me I pray thee why these things are so & by what thou madest them,” in response to which God tells Moses that he would reveal to him “an account of this Earth & the inhabitants thereof.” With that, Moses says, “Tell me concerning this Earth & the inhabitants thereof & also the Heavens & then thy servant will be content.”5

While we do not know what Joseph Smith was anticipating at the start of this revelation, the text itself tells us that it is the prologue to the Genesis creation account with which the Bible begins. God tells Moses, “I will speak unto you concerning this Earth upon which thou standest & thou shalt write the things which I shall speak.” But he then says that the day would come when people would “esteem my words as naught & take many of them from the Book which thou shalt write,” foretelling the rejection and removal of much of the revealed narrative. As a consequence, “I will raise up another like unto thee & they shall be had again among the Children of men among even as many as shall believe.”6

[Page 92]Did Joseph Smith understand these words as foretelling the restoration of lost material from the Bible? And did he understand them as instructions to him to restore that lost material?

Immediately after the Visions of Moses on the manuscript, we have a new heading: “A Revelation given to the Elders of the Church of Christ On the first Book of Moses.”7 Then come these words: “And it came to pass that the Lord spake unto Moses saying Behold I reveal unto you concerning this Heaven & this Earth[,] write the words which I speak … yea in the beginning I created the Heaven & the Earth upon which thou standest & the Earth was without form & void & I caused darkness to come up upon the face of the deep & my Spirit moved upon the face of the waters for I am God & I God said Let there be light & there was light.”8 These words, in obvious continuity with the words of the Visions of Moses and flowing directly from them, are the first three verses of Genesis. They do not give the impression of having been written to stand at the head of a new document but to continue the text that precedes them. Whether anticipated by Joseph Smith or not, the Visions of Moses is a prologue to the biblical creation account. It provides the context for that account within a discussion of God’s creations throughout the cosmos, and it provides a setting for the telling of the story to Moses. By the time the heading was written, “A Revelation … On the first Book of Moses,” Joseph Smith knew at least that it was to be a Genesis revelation. And after he received the first words of it, he and his scribe certainly knew, if they did not know before, that they were creating a new version of a biblical narrative.

Notwithstanding the continuity of the narrative, the heading that separates the Visions of Moses from Genesis 1 (that is, Moses 1 from Moses 2) constitutes a significant break in the text. It introduces an audience, “the Elders of the Church,” and it likely begins a revelation that took place at a different time and perhaps in a different physical setting from what came before. The heading also introduces a new rhetorical tone with a new voice. The narrator’s voice continues only for a few words—“And it came to pass that the Lord spake unto Moses saying”—after which God becomes the speaker. In addition, the break suggests a procedural separation from the past and the introduction of a new method of producing the text. From that point forward, what the Prophet was creating was a revision of existing biblical words, not a text with no Bible counterpart.

[Page 93]Today it makes sense to view the Visions of Moses as part of the New Translation because Joseph Smith and those who worked on it with him did. As we have seen, Genesis 1 was written immediately following it, beginning on the same page. The entire Old Testament 1 manuscript was preserved in a wrapper labeled “Genesis” (although we do not know when that cover and title were applied). John Whitmer’s copy of the manuscript, created about the first of January 1831, reproduces the text with the Visions of Moses immediately preceding Genesis.9 The same is true of the copy of the text he began in March 1831, Old Testament Manuscript 2. The Visions of Moses on that manuscript has a title that was placed at its top in the hand of Sidney Rigdon—“Genesis 1st Chapter.”10 Through all of these means, the Visions of Moses was “both physically and intellectually associated” with the Bible translation that it introduces.11

Location

We can probably assume that the “June 1830” date at the top of the first page of OT1 represents the month in which the Visions of Moses was dictated. Because the text is only two and one half pages long, we might assume that it was recorded in one or two sittings. One thing that makes that assumption uncertain is a change in ink, from a dark ink to a lighter ink, on the eleventh line of page 2. This would be of little notice because writers had to change ink sources from time to time, but the change corresponds with a significant break in the narrative, as though one chapter were ending and another beginning. It is important not to conclude more from that than is justified, but the break leaves open the possibility of a change of date and a change of venue.

We do not know where Joseph Smith was when the Visions of Moses was revealed. During different parts of June 1830, we have evidence of his being in Harmony, Pennsylvania, and in Colesville and Fayette, New York. The text could have been recorded in any of those locations.

Manuscript and Printed Bible

It is not certain whether the Visions of Moses on Old Testament 1 is the original text written from dictation. The evidence is mixed, suggesting [Page 94]to some that it is a copy of the original. But it is clear that it was not intended for use as a fair copy, that is, a refined copy made to be the master copy for further duplication and publication. A later manuscript, Old Testament 2, was prepared to serve that function. That document is a copy of Old Testament 1 to which have been added all the hallmarks of a fair copy—some refinements in spelling, the addition of punctuation and capitalization, correction of grammatical anomalies, and insertion of chapter and verse divisions.12

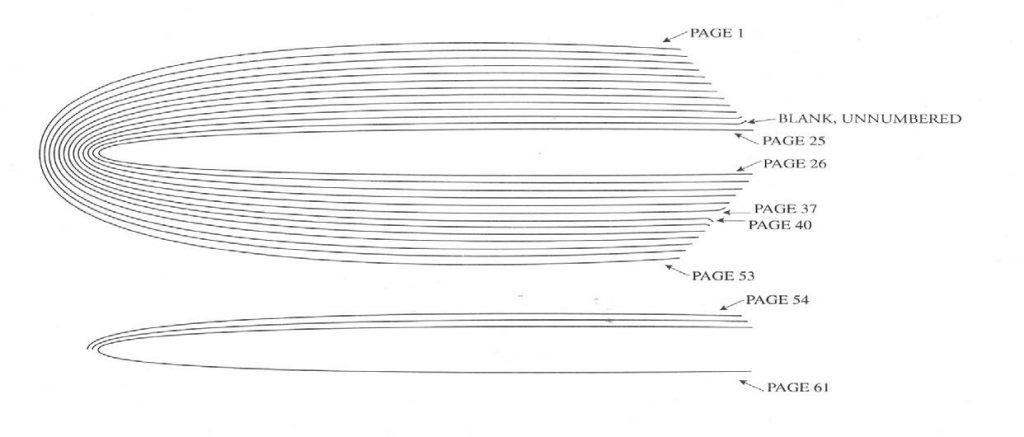

The makeup of Old Testament 1 as a physical artifact leads to questions. The bulk of it consists of a large gathering of sheets of paper. To make such a gathering, thirteen loose sheets of foolscap paper (ca. 16 x 13 inches) were folded in half and stitched in the middle to make a booklet of fifty-two pages. Normally, the writing would be placed on the pages after the booklet was created, but it is possible that sheets were folded and placed inside as the writing progressed, and there is no way to know at what point the stitching was added. These uncertainties are relevant, because they speak to the issue of whether the Prophet anticipated a large writing project when the words were placed on the first page (whether it was the dictated manuscript or not). The gathering begins with the Visions of Moses, and the last page ends at Genesis 21:29.13

[Page 95]In October 1829, while the Book of Mormon was being typeset at E. B. Grandin’s print shop in Palmyra, New York, Oliver Cowdery bought a quarto-size Bible in Grandin’s store for use in the work of the Restoration. He wrote on its flyleaf, “The Book of the Jews And the Property of Joseph Smith Junior and Oliver Cowdery … Holiness to the Lord.” The Bible Cowdery purchased was printed in 1828 by the H. & E. Phinney company of Cooperstown, New York. It would play an important role in the work of the New Translation, and perhaps also in other ways of which we are not aware.14

We know that this copy of the Bible was used in the New Translation, but we do not know if it was used from the beginning. To assess the evidence, we need to first understand the last stage of the process, from February 1832 to July 1833. Starting in mid-February 1832, a year and a half after the translation began, the Prophet and his scribes began using an abbreviated notation system by which they recorded words on the manuscript pages and insertion points in the printed Bible. Joseph Smith dictated to his scribes only chapter and verse numbers and isolated words or phrases, and that is all they wrote on the manuscripts. But in the Bible, he circled words or wrote marks to show where to put the replacement words that the scribes wrote on the manuscripts. Prior to February 1832 there was a different system. The Prophet dictated the text in full to his scribes, who wrote in longhand the words he spoke, in complete sentences and even including passages that had no changes. During that time, the text was recorded exclusively on the manuscript pages, without any notations in the Bible. Thus there is no evidence in the Bible to show that he used it for the translation before February 1832. Because he clearly used it after that date, it is not unreasonable to suppose that he used the same Bible from the beginning of Genesis as well.

From Genesis 1:1 on, the New Translation is a revision of existing King James translation text. Because of that, it seems evident that Joseph Smith had a Bible in front of him during the translation and that he read from it while his scribes wrote. When he came to a passage needing revision, he would dictate words not found in the printed text until he came back to that text and continued with it. The writing on the manuscripts shows no indication of when the text was coming out of the printed Bible and when it was not. Unless they knew the passages well, [Page 96]the scribes may not have known when he was simply reading and when he was uttering words not found on the printed page.

But we do not know if Joseph Smith had the Bible open in front of him when the Visions of Moses was revealed. As we have seen, we do not know if he knew he was going to do a Bible revision at that time, and nothing in the Visions of Moses would have required the presence of a Bible. If he knew from the outset that he was beginning a Bible revision, he may have had it before him, only to discover that the first installment would be a special prologue to Genesis 1 not in need of a Bible at hand. Otherwise, he likely brought out the Bible only when he knew he was to begin revising its text, which must have happened at Genesis 1:1 or soon thereafter.

Joseph Smith as Bible Translator

In a revelation given the day the Church was organized, Joseph Smith was told that he would be called a translator.15 Because that was about eight months after the Book of Mormon had gone to press, the title seems to anticipate future works of translation, not only those in the past. At what point did he know he had translation responsibilities beyond the Book of Mormon? Did that revelation cause him to conclude that the Bible would be his next task? As we have seen, the Visions of Moses teaches that some text from Moses’s record would be lost and that God would raise up someone like Moses through whom it would be restored. In the Book of Mormon, an angel told Nephi of the removal of plain and precious truths from the Bible (1 Nephi 13:21–29). Did those passages tell Joseph Smith that the Restoration in which he was engaged would include the restoration of the Old and New Testaments? None of the extant revelations contain instructions in the voice of God commanding his prophet to translate the Bible, but such instructions may not have been necessary if he came to understand through passages like these that correcting the Bible was already part of his calling.

The message seems to have been reinforced as time progressed. In July 1830, after the Visions of Moses was revealed, he was instructed in a revelation, “Thou shalt continue in calling upon [God] in my name & writing the Things which shall be given thee by the Comforter. … & it shall be given thee in the very moment what thou shalt speak and [Page 97]write.”16 At about the same time, he and his scribes, Oliver Cowdery and John Whitmer, were instructed, “Ye shall let your time be devoted to the studying the Scriptures.”17 That same month, his wife, Emma Smith, was also called to serve as a scribe, and two pages of Genesis are in her handwriting.18 By the end of the year, instructions for the Bible revision were coming more clearly. When Sidney Rigdon was called to serve as a scribe, God instructed him, “Thou shalt write for him[,] & the scriptures shall be given even as they are in mine own bosom to the salvation of mine own elect.”19 These words, coming when the translation was well into the account of Enoch in Genesis 5, show that at least by then the Prophet and those who worked with him knew both that they were providing a new rendering of the Bible and that their work was an important part of the Restoration.

Go here to see the 3 thoughts on ““The Visions of Moses and Joseph Smith’s Bible Translation”” or to comment on it.