Part 1 ⎜ Part 2 ⎜ Part 3A ⎜ Part 3B ⎜ Part 3C ⎜ Part 3D ⎜ Part 3E ⎜ Part 4 ⎜ Part 5 ⎜ Part 6 ⎜ Part 7 ⎜ Part 8 ⎜ Postscript

Forgeries, Unprovenanced Artifacts,

and Pseudo-Archaeology

Latter-day Saints who accept the historicity of the Book of Mormon have long sought external archaeological verification for ancient Nephites and Lamanites.[1] Whether out of a desire to “prove” the Book of Mormon is true or bolster a particular geographical setting for the book, “Book of Mormon archaeology” has been the focus of much interest amongst Latter-day Saint scholars and laypersons. The Annotated Edition of the Book of Mormon (AEBOM) enters this discussion by offering archaeological artifacts which the editors David Hocking and Rod Meldrum claim either support a “heartland” setting for the Book of Mormon or somehow illustrate descriptions of material culture, warfare, agriculture, and metallurgy in the Book of Mormon. In that sense, the AEBOM attempts what John L. Sorenson undertook in the late 1990s but for a “heartland” as opposed to Mesoamerican setting for the Book of Mormon.[2]

However earnest the editors of the AEBOM might be in their attempt to provide archaeological evidence for situating the Book of Mormon in the “heartland” of North America, their efforts are severely undermined by the inclusion of unprovenanced artifacts, artifacts which have been wrested from their proper archaeological or historical context, or are (strongly) suspected forgeries. In other words, the editors of the AEBOM approach archaeology with enormous carelessness and an overall untrustworthy methodology. This fundamentally compromises the usefulness of the AEBOM in presenting a reasonable (or even believable) archaeological profile of Book of Mormon peoples.

Old World Artifacts

The Book of Mormon opens in the ancient Near East (Jerusalem circa 600 BC). Naturally, Latter-day Saint scholars have turned their attention to this region of the world in attempts to situate the Book of Mormon in just such an ancient setting. The AEBOM does this as well, although not as carefully as one might hope. For instance, the AEBOM cites the Amarna Letters (3) in discussing the phrase “land of Jerusalem” found in the Book of Mormon. However, the AEBOM does not provide the date for these letters, giving the impression that they are more contemporary to Lehi than they really are.[3] Likewise, the AEBOM compares the dagger of king Tutankhamun with the description of the sword of Laban given in the Book of Mormon (5). In its description of Tutankhamun’s dagger, the AEBOM gives the impression that the blade was “of most precious steel” like Laban’s sword. In fact, the blade of Tutankhamun’s dagger is meteoric iron, not steel. The comparison generally to the sword of Laban is legitimate, but the AEBOM is not careful in how it makes that comparison.[4]

When dealing with legitimate archaeological and linguistic evidence for the Book of Mormon, the editors of the AEBOM garble the details in a way that results in factual inaccuracies and, frankly, nonsensical statements. Consider, for example, the claims made about Nahom in the AEBOM.

- The caption to a map showing the “Probable Route Taken by Lehi’s Family” states that, “Of note is the place called Nahom, recently identified as a burial place with stone markers inscribed with ‘NHM.’” (30). Inscriptions from the ancient Barʾān temple mention a member of the NHM tribe, and within or near the NHM tribal territory there are ancient burial grounds.[5] But the inscriptions were not found in a burial place, and there is no burial place with stone markers inscribed with NHM; this simply does not exist.

- The textbox for “Nahom” summarizes Alan Goff’s work on the Hebrew root nḥm and its appropriateness for the Nahom narrative.[6] It states, “Adding the vowel ‘a’ to NHM, the word naham means ‘to mourn,’ to come to terms with death” (31). Here, the editors of the AEBOM appear to misunderstand the nature of Hebrew language and writing. They seem to think that adding the vowel a changes the meaning of the nḥm But ancient Hebrew is written without vowels and naḥam is simply the spelling out of the nḥm root with vowels added.

- Referring back to their summary of Goff’s paper, the editors of the AEBOM state, “This theory is corroborated by a huge area of ancient burial tombs at ‘Alam, Ruwayk, and Jidran” (p. 31). This does not make any sense. The meaning of the Hebrew root nḥm has nothing to do with the discovery of the necropolises at ʿAlam, Ruwayk, and Jidran in Yemen, and their discovery certainly does not “corroborate” the Hebrew meaning in anyway. The two things are completely unrelated.

- Still talking about the discovery of the necropolises at ʿAlam, Ruwayk, and Jidran, the AEBOM states they were excavated “at approximately the same time that the Bar’an excavation was completed” (31). This is true, but likely confusing to the reader, since the AEBOM never explains what the Barʾān excavation is and the mention of the altars, discovered at Barʾān, comes after.

- The AEBOM follows their assertions about ʿAlam, Ruwayk, and Jidran with the claim, “This area in southern Arabia has been certified by recent Journal publications that have featured three inscribed limestone altars discovered by a German archaeological team in the ruined temple of Bar’an in Marib, Yemen” (31). It is hard to even know what the editors could mean by “certified” here, but nothing about the discovery of the altars “certifies” anything about the burial grounds at ʿAlam, Ruwayk, and Jidran, which is the “area in southern Arabia” they were just talking about.

- The AEBOM incorrectly translates the names Biʿathtar and Nawʿum, from the altar inscriptions, as “Bicathar” and “Nawcân” (31) apparently mistaking the symbol of the South Arabian ayn (ʿ) as the letter c.

The inability of the editors of the AEBOM to get the basic facts right when dealing with Nahom does not inspire confidence in their ability to correctly interpret data from North American archaeology and apply it to the Book of Mormon.

Breastplates, Helmets, and Weapons

The Book of Mormon provides details about the kinds of armor used by the Nephites and Lamanites in military contexts. The text specifically reports that the use of breastplates, head-plates, and shields. William J. Hamblin has provided examples of how these descriptions of armor in the Book of Mormon fit a Mesoamerican context.[7] The AEBOM offers its own examples of Hopewell “breastplates” and “headplates” [sic] that it associates with warfare passages in the Book of Mormon such as Alma 43:19 (289).

The problem with the “breastplates” and “headplates” used in the AEBOM is that they were emphatically not pieces of armor used in combat. They were, instead, ceremonial accouterments. The “headplates” shown in the AEBOM were meant to imitate the look of certain sacred animals (such as hares and deer) used in religious and burial practices.[8] For the same obvious reason that Vikings did not actually run into battle wearing helmets with large horns on them (despite what Romantic nineteenth century paintings would depict), the Hopewell did not go into battle wearing these ceremonial deer antlers: all it takes is an enemy combatant to give them a good yank to throw you off balance or even break your neck and render you incapacitated.

The “breastplates” cited in the AEBOM don’t fare much better than the “headplates.” True enough, the ancient remains of many Hopewell Indians have been uncovered adorned with these copper pectorals. But like the ceremonial animal headdresses (“headplates”) discussed earlier, they were not used in warfare. “There is no evidence that [the copperbreast plates cited in the AEBOM] were used as shields” or body armor in combat.[9] Rather, they were likely social markers, divinatory instruments, and body adornments.[10] The AEBOM does not provide a scale for these copper “breastplates” in the provided photographs on p. 289. Their average size is 8-10 inches long and 4-6 inches wide.[11] In other words, the “breastplates” that Hocking and Meldrum want the Hopewell Nephites running into battle with are about the size of a license plate. While the Nephites certainly were expected to exercise faith in God for their deliverance from the Lamanites, I can imagine them being somewhat incredulous at Captain Moroni proposing to outfit them with “armor” that leaves 90% of their torso exposed.

Finally, the AEBOM provides a picture of a sword from the Museum of Classical Archaeology at Ohio State University in conjunction with the passage in Alma 24:16 (251). The AEBOM comments that “weapons (tomahawks, hatchets, swords, etc.) were to be buried, or otherwise stored, in time of peace” among members of the Iroquois Confederacy. Evidently the AEBOM sees this as a parallel with the passage in Alma 24. What is confusing, however, is what this particular sword may have anything to do with the Book of Mormon or the Iroquois Confederacy. The image is taken directly from the museum’s website, but the assemblage of artifacts in the photo (with the exception of an obvious Cuneiform text) appears to be either Greek or Roman, not Iroquois. After all, the museum is one of Classical archaeology, or “the study of the art, architecture, and culture of the ancient Greeks and Romans, on the basis of their archaeological remains.”

Likewise, the “long-blade weapons” pictured on p. 162 are not accompanied by adequate documentation to establish their provenance (more on this below). In fact, they aren’t accompanied by any documented provenance. Not only that, AEBOM actually provides two contradictory captions for these items. One caption says the “long-bladed weapons shown above represent the many forms of swords that have been discovered in North America.” But a second caption more cautiously notes that “some, none, or all of the specimens pictured . . . may have served as Sword [sic].” So which one is it? Do they all “represent the many forms of swords” found in North America, or do only “some” of them, or do “none” of them? How can we know? And how can we know if any of these objects even date to Book of Mormon times or were used as “Sword”? They might just as well have been agricultural tools from the Late Woodland Period (circa AD 600–1200). Or they might be post-Columbian forgeries. Without any documentation, we’re left in the dark, and are forced to take Hocking and Meldrum’s contradictory word for it.

Fortifications

As with breastplates, helmets, and weapons, the Book of Mormon describes the construction of fortifications and other defensive works by both Nephites and Lamanites. And as with breastplates, helmets, and weapons, the Book of Mormon’s fortifications have been situated in a plausible Mesoamerican context.[12] The AEBOM attempts to do the same but in a “heartland” setting. To do this, the AEBOM cites the following examples as “fortifications” in North America:

- Stone Fort, Giant City State Park, Illinois (287)

- Pounds Hollow Recreation Area, Shawnee National Park, Harrisburg, Illinois (287)

- The Newark Earthworks (303)

- Fortified Hill, Butler County, Hamilton, Ohio (307)

- Fort Hill, Ohio (311)

What do we know about these sites and how well do they match the descriptions and chronology given in the Book of Mormon? For starters, the “fortifications” at Stone Fort and Pounds Hollow in Illinois (along with the rest of southern Illinois’ pre-historic Native American fortifications) date to no earlier than circa AD 600–1000.[13] What’s even worse for the AEBOM is the observation of Jon D. Muller that “by military standards, the surviving portions of these forts are not impressive. They may, of course, have had more substantial timber works above the surviving low stone walls, but even so, their function may not have been primarily defensive in a military sense.”[14] The use of these “forts” as defensive fortifications does not appear to have been their primary purpose.[15]

Fortunately for the AEBOM, Fort Hill in Ohio does date to right time period (circa 2,000 years ago). Unfortunately for the AEBOM, “the term ‘fortification’ may be a serious misnomer, since there is now growing evidence that the embankments served as major ceremonial rather than defensive features.”[16] Despite its misleading name, Fort Hill (along with other “forts” in Ohio, such as Fort Ancient, Fortified Hill, Miami Fort, Carlisle Fort, and West Carrolton Fort Works) is more properly a “hilltop enclosure,” not a defensive fort. “The many openings in their walls (‘gateways’) and their considerable size relative to the small populations expected to have inhabited the area . . . render them untenable as forts.”[17]

This is also seen in Fortified Hill in Ohio (built circa AD 300–700).[18] Describing the very sketch reproduced in the AEBOM (307), Gerard Fowke writes, “It is difficult to see how they could be of any particular service as a means of defense. There is a narrow ridge connecting the part of the hill on which the enclosure stands with the higher table-land beyond; but the secondary walls extend some distance to each side of this and are either opposite to slopes less easy of ascent than at other points not so strongly defended, or else are so placed that an intruder could not be seen from them until he had surmounted the outer wall. In case a determined rush should admit an enemy, the defenders would be in a trap.”[19]

Finally, what about the Newark Earthworks? The Newark Earthworks in Newark, Ohio were built circa 2,000 years ago, so the dating is a match with the Book of Mormon. What is not a match with the Book of Mormon, however, is the fact that the “they were not cities, for little evidence of domestic activities is found here. Nor are they fortifications, as some early European Americans [such Squier and Davis cited in the AEBOM] believed. Hopewell shamans undoubtedly performed ceremonies at these sites, including mortuary rituals at particular locations. . . . They were social gathering places, religious shrines, pilgrimage centers, and even astronomical observatories.”[20] Whatever relevance the AEBOM implies (303) the non-military Newark Earthworks hold for Moroni’s military fortifications described in Alma 48 is not immediately obvious.[21]

What should have been a dead giveaway for Hocking and Meldrum that the Newark Earthworks were not defensive fortifications is the fact that the picture they provide (303) of the ditch at the Great Circle is on the inside of the earthworks. This interior ditch was the result of “builders obtain[ing] . . . dark brown earth” for the the creation of the mound proper.[22] This pattern is observed at other Hopewell sites, reinforcing the likelihood that these ditches are not primarily defensive in nature, but rather served in the construction of the mounds and to “demarcate monumental sites.”[23]

Where does this leave us? According to the overwhelming consensus of contemporary archaeologists of Midwestern North America, “even though many [of these sites] are called forts, and early reports referred to some as defensive works, it is unlikely that any of them would have been effective militarily.”[24] This includes every site listed in the AEBOM as evidence for the Book of Mormon’s military fortifications. As is their habit, Hocking and Meldrum are appealing to scholarship that is decades, even over a century, out of date.

New World Cement

The Book of Mormon records that cement was a building material used by the ancient Nephites (Helaman 3:7, 9, 11). Once considered an anachronism for the Book of Mormon, subsequent archaeological research has revealed that cement was in fact a building material used by people in ancient Mesoamerica and is therefore not problematic for the Book of Mormon as once supposed.[25] The AEBOM recognizes the significance of the mention of cement in the Book of Mormon and discusses such in many places (63, 349, 383). However, the AEBOM plays fast and loose with the archaeological evidence for “cement” in North America. For instance, the “stucco ‘cement’” the AEBOM points to on p. 349 isn’t limestone mortar but hardened clay stucco. The AEBOM even acknowledges this, and so puts “cement” in quotation marks. (This is, incidentally, rather odd, since the AEBOM claims on p. 63 that limestone mortar would have been “abundant” in the supposed North American “heartland” setting for the Book of Mormon. If this is the case, then why settle for clay stucco?) Additionally, the AEBOM points to Angel Mounds in southwest Indiana as containing “defensive walls made of timber and plastered with a type of cement” (p. 383). What the AEBOM leaves out is that Angel Mounds were built between ca. AD 1000 and 1450, much too late for Book of Mormon peoples.[26] Furthermore, the “cement” used in the stockades at Angel Mounds is wattle and daub (in this case mud and grass), not limestone mortar.[27] While one might be able to get away with calling this “cement” in a very loose sense, to imply, as the AEBOM does, that it is genuine limestone mortar cement is misleading. It is also misleading not to provide the dating for these sites, as they post-date the Book of Mormon by many centuries.

On the whole, the evidence from Mesoamerica for New World cement as a building material is much more compelling than the examples from the “heartland” adduced in the AEBOM. Not only is the cement from Mesoamerica actual limestone mortar, but it dates to the same time period as the Book of Mormon and was in use in the area considered by some Book of Mormon scholars to be the land northward (where it is reported the Nephites first used cement). In terms of sheer archaeological propinquity, Mesoamerica beats out the “heartland” when it comes to cement in the Book of Mormon.

Unprovenanced Artifacts

When used in archaeological study, the word provenance “denotes the origin or source of an object or idea or may indicate its history of ownership.” When archaeologists speak of determining an artifact’s provenance (or sometimes provenience) they are talking about “discern[ing] where [the artifact or object was] produced” as well as “the place or location at which the object was found or discovered, . . . the context of its finding, . . . what is the source of the object,” and “how the object was relocated from its place of origin to location at which it was recovered.”[28] Being able to document the archaeological provenance of a given artifact or object (not just the origin of its creation but the history of its ownership) is crucial in order to ensure the artifact or object is being interpreted properly and to draw sound, safe conclusions from the data. Unprovenanced artifacts (often looted artifacts, artifacts obtained from the antiquities market, or artifacts from private collections) are often regarded as problematic or suboptimal compared to artifacts uncovered in controlled digs because the odds of successfully passing off forgeries or misunderstanding crucial archaeological context increases with the former. Unprovenanced artifacts are not intrinsically useless in archaeological study, but they are often (and understandably) treated with more skepticism or caution than objects uncovered in controlled digs.

The AEBOM cites multiple unprovenanced artifacts as evidence. This includes:

- nprovenanced arrowheads and axeheads (120).

- n “ancient gold coin” recovered near Deer Creek, Ohio (124).

- everal “long-blade weapons” that are claimed to “represent the many forms of swords that have been discovered in North America” (162).

- Hopewell-era stone carvings of white and black lambs” (385).

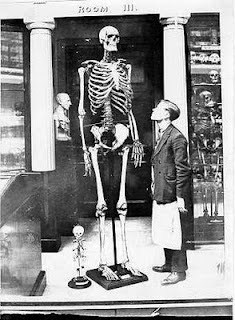

- Giant” skeletal remains (459).

- n unprovenanced “very large ax” found in New York state (460). Hocking and Meldrum do not so much as even give us the name of the alleged discoverer, referring to him only as “a man from the Seneca Nation.”

Because these objects are presented in the AEBOM without any kind of documented provenance, we have no way of knowing if they are authentic, when they date to, where they are from, what they were used for (e.g. ceremonial vs. practical use), and many other contextual details needed to do proper archaeology. Take the “ancient gold coin” above as just one example. The most I could find about this coin online was from the website of J. Huston McCulloch, who can be no more precise than to say the coin was found “in a plowed field about 3-4 miles above the confluence of Deer Creek” in 1967. What’s more, instead of being gold, “it appears to be bronze or perhaps lead.”[29]

So we have a coin of undetermined metal (Gold? Bronze? Lead?) found in a non-controlled and disturbed (“plowed field”) environment by a non-specialist who was recklessly “hunting for Indian artifacts” with no clue as to how it got there, when it got there, who put it there, or whether it’s even authentic. And yet Hocking and Meldrum in the AEBOM have no problem using this as evidence for the Book of Mormon.

And what about the “giant” skeleton used in the AEBOM (459) to illustrate the description given in Ether 1:34 of the Brother of Jared being “a large and mighty man”? The picture (seen right) is juxtaposed next to a clipped 1925 newspaper article with the sensational headline: “Mound Giants in Indiana Said to Antedate Indian.” However, the AEBOM provides no documentation for when and where the photograph was taken, who took the photograph, and what the “giant” skeleton in the photograph really is. The obvious goal here in the AEBOM is to associate the “giant” skeleton with the newspaper article describing “giants” discovered in a mound in Indiana and thereby link Ether 1:34 with these findings.

And what about the “giant” skeleton used in the AEBOM (459) to illustrate the description given in Ether 1:34 of the Brother of Jared being “a large and mighty man”? The picture (seen right) is juxtaposed next to a clipped 1925 newspaper article with the sensational headline: “Mound Giants in Indiana Said to Antedate Indian.” However, the AEBOM provides no documentation for when and where the photograph was taken, who took the photograph, and what the “giant” skeleton in the photograph really is. The obvious goal here in the AEBOM is to associate the “giant” skeleton with the newspaper article describing “giants” discovered in a mound in Indiana and thereby link Ether 1:34 with these findings.

There are several problems here. First, the October 23, 1925 Evening News article cited in the AEBOM (which, based on the watermark at the bottom right, the editors appear to have taken from this website) next to the photo is not describing the skeleton in the picture. We know this for two reasons. First, we have the surviving reports that let us know the “mound giants” were not abnormally-large superhumans. This was a fanciful exaggeration in the press (including the newspaper cited in the AEBOM).[30] Second, the skeleton in the photo is not that of an ancient Native American from Indiana. It’s actually the skeleton of Charles Byrne, an Irishman who suffered from gigantism and died in 1783. His skeleton (the one in the photo used in the AEBOM) is housed at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. The college has a photo of the skeleton in their archives with full documentation of ownership, and reputable press reports (such as this Associated Press story and this Smithsonian Magazine story and this JSTOR Daily story) have written about Byrne and the controversy surrounding his remains. (The smaller skeleton in the photo is that of Caroline Crachami.) This article at least matches the picture in the AEBOM with the right story, although it still does not give documentation for who took this photo and where it is archived.

“Museum attendant with the skeleton of Charles Byrne and the skeleton of Caroline Crachami”

So the AEBOM takes an uncredited photo of an Irish skeleton from the 18th century, juxtaposes it with a sensationalist headline that garbled accurate field reports, and tries to pass this off as evidence for the Book of Mormon. It is difficult not to conclude that the editors of the AEBOM simply did a google search for “giant skeleton North America” and took the image from a conspiracy website (such as this one or this one) without bothering to check the accuracy of the details, then slapped it together with an unrelated (and misleading) newspaper article to shoehorn Ether 1:34 into a “heartland” setting.

This is, to say the least, emphatically not how proper archaeology is done.

Finally, the AEBOM cites what it calls a “Hebrew Petroglyph Panel” (544). The identity of this source is puzzling. The AEBOM describe this piece as “found by Ron Rigoni on his 10,000 acre ranch [in Conchas Lake, New Mexico] and examined as authentic by Scott Wolter, American Petrographic Services Inc.” A Google search for these details only bring up websites associated with the “heartland” movement that repeat this same information (sometimes verbatim). I have so far been unable to find any details about this “petroglyph panel,” or Mr. Rigoni, or the work done by Scott Wolter with American Petrographic Services Inc. which supposedly authenticates this piece. I have not found any publications in peer-reviewed academic journals verifying the claims made in the AEBOM that Mr. Wolter has authenticated this item to the satisfaction of other epigraphers and North American archaeologists. In fact, when I spoke to Mr. Wolter over the phone, he was unable to remember authenticating this “Hebrew Petroglyph Panel” and thought that maybe I was confusing it with the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone. When I informed him that the AEBOM lists the Los Lunas Stone and the “Hebrew Petroglyph Panel” as two separate objects, he reiterated his unfamiliarity with the latter, saying it “didn’t ring a bell” to him.[31]

When you provide no documentation for the claim that this piece is evidence for “Hebrew written language and culture” in North America (544) and when even the very expert you cite for its authentication can’t remember authenticating such, you know you have a problem.

Forgeries

As in any other academic discipline, the use of forgeries is a mortal sin in archaeology. If one is going to submit a piece of evidence that is suspected of being a forgery, one must first acknowledge the accusation and then make a vigorous defense of the items’ genuineness if their submission of the evidence is even going to be given the slightest bit of serious scholarly attention. Otherwise, the prevailing assumption is that the suspected forgery is guilty until proven innocent.

If the AEBOM‘s use of unprovenanced artifacts is questionable, its use of suspected or demonstrable forgeries is orders of magnitude worse. The items cited by the AEBOM that are considered forgeries by mainstream Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saints scholars include:

- The Los Lunas Decalogue Stone (130, 544)

- The Bat Creek Stone (131, 544)

- The Newark Holy Stones (544)

- The Tucson Lead Artifacts (544)

The dubious nature of the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone, the Bat Creek Stone, and the Newark Holy Stones has been discussed by a Book of Mormon Central KnoWhy.[32] In short, while these inscriptions do have their proponents, none of them have been accepted by the academic community as genuine beyond reasonable doubt. The AEBOM doesn’t so much as mention the controversy surrounding these objects, let alone take the time needed to make a case for their authenticity (and thus their admissibility as evidence.)

The Book of Mormon Central KnoWhy does not discuss Tucson Lead Artifacts, so it’s worth mentioning something about them here. These objects have encountered serious skepticism and accusations of being forgeries. A near-exhaustive study of these artifacts undertaken by Don Burgess leaves little doubt to their being fakes.[33] The AEBOM‘s claim that the Tucson Lead Artifacts “were declared as authentic following a scientific investigation by Scott Wolter” is insufficient for overturning Burgess’s work. That may well be the case, but how can we know? What investigations did Mr. Wolter undertake? Where were his findings published? Did they pass basic peer review and have they been replicated? These are crucially important questions that the editors of the AEBOM must answer before they can admit the Tucson Lead Artifacts as evidence.

The AEBOM fails to provide even the minimum amount of scholarly care needed to pass as reliable archaeological commentary on the Book of Mormon. Whatever small pieces of usable archaeology may be present in the volume (yes, it’s true that North American Indians did know how to work copper during Book of Mormon times, as discussed in the AEBOM) are overshadowed by the many glaring problems and compromising mistakes made therein.

Endnotes

This article is cross-posted with the permission of the author, Stephen O. Smoot, from his blog at https://www.plonialmonimormon.com.