[Page 55]Abstract: Scriptural accounts of celestial beings visiting the earth are abundant in both the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Whether a descending deity or angelic beings from celestial realms, they were often accompanied by clouds. In this paper a short analysis of the various types of clouds, including imitation clouds (incense), will be discussed. The relation between the phenomenon of supernatural beings, sometimes in clouds, may have had a great influence on descendants of Book of Mormon cultures. For these people, stories that were told from one generation to the next would have been considered ancient mythological lore. It may be plausible that future generations attempted to duplicate the same type scenario of celestial beings speaking and visiting their people. These events were sometimes recorded in stone.

Little is said about the extraordinary way the resurrected Christ took his leave after special visits, both in Jerusalem and on the Western Hemisphere (Acts 1:3, 9–11; 3 Nephi 18:38–39). In Jerusalem, Christ sojourned for forty days after his resurrection for the purpose of teaching his apostles. On one occasion, as he took his departure from them, a cloud received him as he was taken up. Two men in white apparel stood by the apostles and said, ”Why stand ye gazing up into heaven? This same Jesus, which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as ye have seen him go into heaven.” The two men, arrayed in white, were angels of the Lord. One may assume they, too, ascended to the heavenly realms after their visitation.

Psalm 18:9–11 mentions darkness, clouds, a cherub (a celestial being), and the Lord’s pavilion. These things are apparently related. I will be examining phrases and words such as “clouds of light” or “glory,” “clouds of darkness,” “incense” or “smoke,” “the sun,” and their association with visions and celestial visitations in both biblical [Page 56]scripture, the Book of Mormon, and in Mesoamerican tradition, where Latter-day Saint archaeologists have demonstrated the core narrative of the Book of Mormon took place.1

Writings in biblical scripture pertaining to heavenly visitations accompanied by clouds have a similar correspondence to Mesoamerican depictions of supernatural beings appearing in the heavens, both with and without clouds. Clouds, in particular in Mesoamerican thought, are a metaphor for the heavens,2 and are often associated with visitations of divine beings.

Aphrahat, a fourth-century Syriac-Christian Father, had the opinion that clouds (standing, riding, or sitting on clouds) are a common attribute of biblical divine appearances.3 The dreams or visions where they are seen are called theophanies (Greek for “God appearances”). Margaret Barker, a scholar of Judaism and Early Christianity explains, “The cloud was the usual sign of theophany.”4 For example, in Ezekiel’s vision he saw a cloud of light. He writes in chapter 10, verse 4, “Then the glory of the Lord went up from the cherub, and stood over the threshold of the house; and the house was filled with the cloud, and the court was full of the brightness of the Lord’s glory.”5 Taken together, this passage and the following verses describe a “cloud of light.”

Another very important scripture that pertains to clouds and heavenly visitations is Daniel 7:13: “I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to [Page 57]the Ancient of days, and they brought him near before him.” There are numerous passages in the Old Testament with similar theophanies, which strengthens the necessity for God to communicate with man, oftentimes with the accompaniment of clouds.

In the New Testament, Jesus foretells of the devastation and signs preceding his second coming, saying, “And then shall appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven: and then shall all the tribes of the earth mourn, and they shall see the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven with power and great glory” (Matthew 24:30). And again in Matthew 26:64: “Jesus saith unto him [a Jewish high priest], Thou hast said: nevertheless I say unto you, Hereafter shall ye see the Son of man sitting on the right hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven.”

John the Revelator also prophesies the words of Christ in Revelation 1:7 when he wrote, “Behold, he cometh with clouds; and every eye shall see him.” Further on in Revelation 14:14 John recounts a vision: “And I looked, and behold a white cloud, and upon the cloud one sat like unto the Son of Man, having on his head a golden crown, and in his hand a sharp sickle.” A cloud is also mentioned in verses 15–16.

Jesus took Peter, James, and John to the Mount of Transfiguration, where Moses and Elias appeared to them (Mark 9:2–4). Peter proposed they build three tabernacles, one for the Lord, one for Moses, and the other for Elias (Mark 9:5). Immediately after Peter’s suggestion, the following ensued: “And there was a cloud that over-shadowed them: and a voice came out of the cloud, saying, This is my beloved Son: hear him” (Mark 9:7). The aforementioned biblical scriptures speak of clouds of light that are full of power and brightness of the Lord’s glory.

Now we turn out attention to “clouds of darkness.” For example, when Moses was leading the Israelites out of Egypt, Exodus 14:20 reads, “And it came between the camp of the Egyptians and the camp of Israel; and it was a cloud and darkness, but it gave light by night: so that the one came not near the other all the night.”

Reading further in Exodus 19:9: “And the Lord said unto Moses, Lo, I come unto thee in a thick cloud, that the people may hear when I speak with thee, and believe thee for ever. And Moses told the words of the people unto the Lord.” And then in Exodus 24:15–16: “Moses went up into the mount, and a cloud covered the mount. And the glory of the Lord abode upon mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it six days: and the seventh day he called unto Moses out of the midst of the cloud.” Following this, Moses’ theophanous experience is recorded in Exodus [Page 58]34:5: “The Lord descended in the cloud, and stood with him there, and proclaimed the name of the Lord.”

Moses in Deuteronomy 5:22 mentions a cloud of thick darkness: “These words the Lord spake unto all your assembly in the mount out of the midst of the fire, of the cloud, and the thick darkness, with a great voice: and he added no more. And he wrote them in two tables of stone, and delivered them unto me.”6 For Moses it was a revelation and instruction. For the wicked the “cloud, and the thick darkness” was a terrible warning, as the Israelites were worshipping a molten calf when Moses descended the mountain carrying the tablets (Exodus 32:4). In contrast to clouds of light, clouds of darkness have a foreboding quality — a warning from the Lord that the viewer needs to take heed and listen.

Clouds are an interesting phenomenon in the scriptures. If they are natural, it is due to atmospheric conditions. If they are intentional for a specific purpose, the Lord creates them; and if the Israelites wanted to make a cloud, they used incense or burnt offerings. For example, Leviticus 16:13 reads, “And he [Aaron] shall put the incense upon the fire before the Lord, that the cloud of the incense may cover the mercy seat that is upon the testimony, that he die not.” Similarly, Ezekiel 8:11 reads, “And there stood before them 70 men of the ancients of the house of Israel, and in the midst of them stood Jaazaniah the son of Shaphan, with every man his censer in his hand; and a thick cloud of incense went up.”

The Lord commanded Moses and Israel to use incense (Exodus 40:27; 1 Chronicles 23:13; 1 Samuel 2:28). However, other people besides the Israelites also used incense, and they were condemned by the Lord for burning incense to idols (Jeremiah 1:16; 48:35). Even the Israelites on various occasions offered incense, made sacrifices, and offered prayers to the idolatrous Baal (2 Kings 23:5; Jeremiah 11:12–13, 17). The burning of incense was a primary ritual function among the Israelites, apparently not always employed as it was intended by the Lord. It was to be used as a cloud covering at the altar of God, and the prayers of the high priest, similar to the incense smoke, would ascend to the heavens.

Latter-day Saints believe some of the New World’s ancestors came from the Near East as recorded in the Book of Mormon. Mesoamerican cultures also used incense in their ceremonies. Incense burners were ubiquitous in Mesoamerica, varying in size, shape, and type of medium. [Page 59]John Sorenson observed, “Close correspondences exist between them and certain Near Eastern incense fixtures.”7

Burning incense is just one of the practices and its accompanying symbolism that existed in Mesoamerica that would have been used by the descendants of Lehi that obeyed the Law of Moses.8 We now turn our attention to clouds and divine visitations in the Book of Mormon and examine the same in Mesoamerica.

Around 30 bc, Nephi and Lehi, sons of Helaman, were traveling to the land of Nephi when they were captured by an army of Lamanites who cast them in prison (Helaman 5:21). The Lamanites were about to slay their prisoners when Nephi and Lehi were encircled by a non-consuming pillar of fire while the earth shook exceedingly. This dramatic incident caused their onlookers great fear — they dared not approach these servants of God (Helaman 5:23–27).

Subsequently, a “cloud of darkness” overshadowed Lehi and Nephi like a looming, ominous shelter (Helaman 5:28). A voice came from above through the cloud. It was the Lord speaking to the people crying repentance, but a voice that was still, yet “did pierce even to the soul” (Helaman 5:29–30). The “cloud of darkness” did not disperse until after the message was delivered three times to the Lamanites and the Nephite dissenters among them. They repented of their sins after acknowledging the message they heard in former years (Helaman 5:41–43). A wonderful thing happened — the heavens were opened; in other words, the “cloud of darkness” was lifted to some three hundred people who saw angels descending (Helaman 5:48–49).

The “cloud of darkness” is of great significance here — it acted as a shield to the supernatural of God’s actions, but also had the onlookers attention. The Lord’s voice was heard, the “Holy Spirit of God did come down from Heaven, and did enter into their hearts” (Helaman 5:45) after they repented, and God’s emissaries, the angels, came to administer to the people.

The thick clouds that loomed over the prison holding Nephi and Lehi, and over Lamoni before his conversion, represent transgressions or sins. Isaiah 44:22 reads, “I have blotted out, as a thick cloud, thy [Page 60]transgressions, and, as a cloud, thy sins: return unto me; for I have redeemed thee.” Once these people repented, the thick cloud of darkness became a cloud of light.

We have reviewed some examples in the Bible and the Book of Mormon of “clouds of light” and “clouds of darkness,” both revealing a message from God or his angels.

Chart 1

| Scripture |

Angel(s) Appear To |

Approximate Date First Mentioned |

|

2 Nephi 4:24 |

Nephi |

588 bc |

| 2 Nephi 6:9 |

Jacob, Nephi’s brother |

559-45 bc |

| 2 Nephi 10:3 | Nephi | 559-45 bc |

| Jacob 7:5 | Jacob | 544 bc |

| Mosiah 3:2 | King Benjamin | 124 bc |

|

Mosiah 27:11, 14, 17-18, 32 |

Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah |

100-92 bc |

| Alma 8:14, 18 | Alma | 82 bc |

| Alma 8:20 | Amulek | 82 bc |

| Alma 9:25 | Many people in land | 82 bc |

| Alma 19:34 |

Lamoni’s household |

90 bc |

| Alma 24:14 | Anti-Nephi-Lehies | 90-77 bc |

| Helaman 5:39 | Nephi and Lehi | 30 bc |

| Helaman 5:48-49 | About 300 people | 30 bc |

|

Helaman 13:7, 14:26-28 |

Samuel the Lamanite |

6 bc |

| 3 Nephi 7:15, 18 | Nephi | ad 31-32 |

| 3 Nephi 17:24-25 |

Encircled little children |

ad 34 |

| 3 Nephi 19:14-15 | The Twelve Disciples | ad 34 |

Chart 1 is a list of scriptures recording visitations from an angel or angels in the Book of Mormon after Lehi’s party landed on the American continent. There are many more verses that recount these particular occasions after they first occurred. Perhaps the most significant visitation by angels was in ad 34, when Christ came to Bountiful in his resurrected state. The heavens opened, and angels descended and encircled the little children. “About two thousand and five hundred souls” were witness to this momentous occasion (3 Nephi 17:23–24).

[Page 61]The translated portion of the Book of Mormon is considerably small compared to the vast Nephite library. Therefore, we may have only a limited number of recorded visits by angels. Beginning with 2 Nephi, the approximate dates of these occurrences range from 588 bc to ad 34. Since we are not privy to the entire texts of the Book of Mormon, it is not known how many celestial visitations occurred, but the accounts we do have relate that literally thousands of people (over 2,800) witnessed these manifestations. After ad 400 Moroni wrote regarding the question “have miracles ceased?” He exclaims, “Nay, neither have angels ceased to minister unto the children of men” (Moroni 7:29).

Angels, of course, are not the only supernatural visitors to mortals in the Book of Mormon. The brother of Jared, before he arrived on this continent, saw the Lord before his group’s sea voyage. This is an important story that was no doubt passed down through many generations by Lehi’s descendants. The record in Ether reads, “The Lord came down and talked with the brother of Jared; and he was in a cloud, and the brother of Jared saw him not. And it came to pass that the Lord commanded them that they should go forth into the wilderness, yea, into that quarter where there never had man been. And it came to pass that the Lord did go before them, and did talk with them as he stood in a cloud, and gave directions whither they should travel” (Ether 2:4–5, emphasis added). Notice the emphasis I put on “them.” The Lord communicated not only with the brother of Jared, but Jared’s party of selected families. Four years later, the Lord spoke again to the brother of Jared from a cloud (Ether 2:14).[Page 62]

Chart 2 lists other visitations in the Book of Mormon after the arrival of Lehi’s party. Although not a visitation of deity, the voice of God is mentioned twice in the Book of Mormon. The first was to three hundred people in the land of Nephi in 30 bc, and the second announcing his son, Jesus Christ, in ad 34 in the city of Bountiful.

Toward the end of the Book of Mormon there is also Christ’s visit to Mormon when he was fifteen years old (Mormon 1:15). Then we have the Three Nephites that Christ set apart as his special messengers (3 Nephi 28). Mormon and Moroni were visited and taught by the Three Nephite disciples who had been translated, and these special three translated emissaries may be considered supernatural beings. They were ministering angels for some 300 years until they were withdrawn because of the wickedness of the people around ad 322 (see Mormon 1:13).9

Chart 2

|

Scripture |

Voice of God to: |

Approximate Date First Mentioned |

| Helaman 5:46–47 3 Nephi 11:7 |

Nephi, Lehi, and about 300 souls Announcing Christ to the people in Bountiful |

30 bc ad 34 |

|

Scripture |

Christ’s Visit or Voice To: |

Approximate Date First Mentioned |

| 2 Nephi 2:3–4 2 Nephi 4:26 Alma 9:21 Helaman 5:29–33 Helaman 10:4–11 3 Nephi 9-28 Mormon 1:15 Ether 12:39 |

Jacob Nephi Alma Nephi, Lehi, and 300 souls

Nephi |

588–570 bc 588–570 bc 82 bc 30 bc

23–20 bc

ad 34 |

|

Scripture |

Visitation by 3 Nephites |

Approximate Date First Mentioned |

| 3 Nephi 28:9 4 Nephi 35–37 Mormon 8:11 |

Souls of men in the world To righteous Nephites Mormon and Moroni |

ad 34 ad 201–211 ad 401 |

From these examples in Charts 1 and 2, we see there were many occasions that angels and other celestial/supernatural beings appeared to men, women, and children in Mesoamerica. Such recollections of these stories may have been passed down to their descendants.

I have been using the word “supernatural” because of their nature; this would include angels, deity, and translated beings. According to Webster’s Dictionary, “supernatural” pertains to being above or beyond what is natural or explainable by natural law, or pertaining to, or attributed to God or deities.10

Therefore, we know the people in the Book of Mormon had visits from supernatural beings from their arrival on this continent, most likely until the last of their righteous prophets, Moroni. That is a time [Page 63]span of nearly a thousand years, and even more if we include the Book of Ether and the account of the brother of Jared. In the Book of Mormon, these visitations were usually accompanied by clouds. This phenomenon is depicted numerous times in Mesoamerican art, with or without clouds, and may be significant as an established practice in their religious beliefs.

We now turn our attention to Mesoamerica where the Lamanite culture continued after defeating the Nephite nation, mixing their traditions with any other groups inhabiting the land.11 We can also assume there were Nephites among these people who denied Christ as they were spared by the Lamanites (Moroni 1:2).

Theology held a prominent position in Mesoamerica — there was a great interplay between the supernatural and the natural world in their religious beliefs. It can also be said this is true of the righteous people in the Book of Mormon. Did the descendants of Jared, Lehi, Zoram, and Mulek’s party carry on the tradition of visitations from supernatural beings from the heavens, whether it was real or superficial? If we look to Mesoamerica, the answer may plausibly be “yes.” However, although they may have instituted some of their visionary rituals as a result of Book of Mormon stories passed down orally, a measure of caution must be considered with this proposed thought.

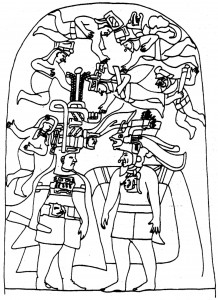

Stela 3 at La Venta, Tabasco, Mexico, is the earliest depiction of supernatural beings peering down from the heavens in Mesoamerica. The significance of this stela can only be conjectured by scholars, as it is a pictorial narrative of a meeting between two individuals with no text. It was carved by the Olmec, most likely between 500–400 bc, a period that may correspond to the end of the Jaredite culture. Some LDS scholars have postulated the man with large aquiline nose and beard is a [Page 64]Mulekite, and the other man facing him, a Jaredite.12 Whether this is the case, we simply do not know. What I find interesting, are the floating personages above in the sky. Do they represent deceased Olmec/Jaredite ancestors? Regardless, they are considered supernatural beings by archaeologists.

The Olmec preceded the Maya, and were highly esteemed by the elite Maya royalty. Even though there are similarities between the Olmec and Maya cultures, there was an emergence of a new form of society with the Maya in architecture and rituals.13

Portrayed on Stela 3, made by the Olmec, the supernatural personages are not seen in a cloud. However, later on among the Maya there are numerous depictions that do show supernatural beings in clouds. Clouds are typically shown in a laying-down S form, which Mayanist Linda Schele called “lazy-S scrolls.”14 The doorway of Temple 22 at Copan, Honduras, is an example, where cloud scrolls embrace ancestral deities.15

The S-shaped scroll was used as a glyph for the word muyal, meaning “cloud” in Classic Mayan texts, and is a metaphor for the heavens.16

The Cotzumalhuapa region in southern Guatemala along the Pacific coast dates from the late Preclassic period [400 bc to ad 250], with the earliest hieroglyphic Maya Long Count date of ad 36–37 on Stela 1 at El Baúl.

This area of Guatemala has numerous monuments that depict descending supernatural beings. This monument has the typical [Page 65]S-curved clouds as seen on many other stelae. Peering down from above is a deified ancestor.

The heavens, figuratively shown as clouds, are still a concept prevailing among some modern Maya Yucatec shamans (priests), who live in the Yucatan Peninsula. The smoke of incense making clouds is considered the soul stuff of the living universe,17 and furthermore, smoke and clouds are synonymous in Maya thought when observing a Maya ritual.18 For Mesoamerican cultures incense was used for purification, but even more aptly, to offer prayers that would rise up in aromatic clouds to the heavens where their gods live.19 This brings to mind Revelation 8:4 in the New Testament: “And the smoke of the incense, which came with the prayers of the saints, ascended up before God out of the angel’s hand.”

Linton Satterthwaite, a Maya archaeologist, observed that incense smoke to the Maya served to hide sacred objects from the eyes of the people.20 The smoke, in a roundabout way, served as a covering. But more important, clouds or incense smoke were the medium where visions occurred among Mesoamerican cultures.21

In The Conquest of Mexico, William H. Prescott incorporates a picture in his book to represent Montezuma’s conjuring a vision of [Page 66]Quetzalcoatl through clouds of incense smoke.22 Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl has a beak-like mask, which is one of Quetzalcoatl’s forms, not because the god looked like that, but this deity wears the accoutrements of his functions. In this case, Quetzalcoatl is a god of air, wind, and the breath of life.23

Figure 4: Montezuma using incense clouds to conjure the deity Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl (drawing by D. Wirth)

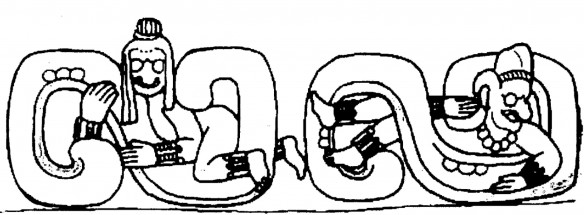

Mesoamerican people performed rituals that in our eyes mimicked the aforementioned visions of Lehi’s descendants. These practices were thought to bring sacred supernatural beings into their presence. From the earliest times in many parts of the Maya region, the serpent was a symbol of the vision rite24 and was sometimes associated with clouds. In illustrations of Vision Serpents, the serpent has an opened mouth [Page 67]bringing forth a supernatural deity, which is often a deceased ancestor, into the land of the living.

At Yaxchilan, Lintel 15 shows a royal lady holding a bowl of papers containing her sacrificial blood. The same type of bowl is below the Vision Serpent, with smoky cloud scrolls emanating upwards like small beads of blood. From this emerges the Vision Serpent. The woman is in a trance after fasting and self-sacrifice of blood — she visualizes what Mesoamerican scholars theorize is an ancestor visiting from the heavens. Royal ancestors were considered deified in the Maya culture.

Today, however, there is no vestige of the Vision Serpent among the Maya.25 Whether or not the Vision Serpent was associated with the Feathered Serpent, Quetzalcoatl, is debatable. Miller and Taube postulate a smoky cloud cross-hatching pattern flanks many Vision Serpents’ bodies, and it is known that the serpent is sometimes seen in art as the Sky Serpent.26 The word for serpent and sky in Mayan sound very similar with a slight phonetic variation: sky caan, and serpent can. In other words, the Vision Serpent was a direct link to heavenly clouds [Page 68]and visions, rather than feathers of the plumed serpent, representing Quetzalcoatl.27

As mentioned above, there are many examples from early Mesoamerican sites of supernatural beings depicted issuing from incense, within clouds, or just appearing above in the air. They are discussed here for their interest in this study, but whether or not they are relevant in actuality in relation to the Book of Mormon cannot be positively determined. However, one more piece of this scenario needs to be considered. It is the “sun” in scripture and in Mesoamerican tradition.

The following quote may refer to a celestial being descending in ancient times in Mesoamerica. Allen Christenson brought to my attention a portion of Dennis Tedlock’s translation of the Popol Vuh:

And then the face of the earth was dried out by the sun. The sun was like a person when he revealed himself. His face was hot, so he dried out the face of the earth. Before the sun came up it was soggy, and the face of the earth was muddy before the sun came up. And when the sun had risen just a short distance he was like a person and his heat was unbearable. Since he revealed himself only when he was born, it is only his reflection that now remains. As they put it in the ancient text, “The visible sun is not the real one.”28

We have looked at several accounts where celestial beings were seen in vision or in reality in the Book of Mormon. In another example in 1 Nephi 1:9, the heavens were opened to the prophet Lehi before he left the Near East: “And it came to pass that he saw One descending out of the midst of heaven, and he beheld that his luster was above that of the sun at noon-day.” In the above quotation from the Popol Vuh, we have a reference of a being as bright as the sun. This statement was written shortly after the Spanish Conquest; nevertheless, it reflects a story from pre-Columbian times.

Today among the Catholic Maya the sun is a symbol of Christ. Chamula, Chiapas, Mexico, has festivals throughout the year, but the greatest of these has men running through a Path of Fire. This Path of Fire is explained in the book Maya Cosmos. It “represents the road of the Sun, a symbol of Christ, across the sky. Running through the [Page 69]thick smoke clouds, the men carry banners of the Sun-Christ back and forth across the flames and coals, east to west and back again, a total of three times.”29 In like manner, at Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, Allen Christenson reports that many refer to Christ as “Our Father Sun” or “Lord Sun,”30 and during church processional ceremonies the people bore the image of Christ surrounded by a sunburst.

Again, it is no surprise that the Maya related Christ with the sun. Their rulers on many ancient monuments have the names of their kings with an additional name of K’inich Ahaw, meaning “Sun-faced Lord” or “Great Sun Lord.”31 What would be greater, more powerful, or life giving than the sun, who these kings chose to emulate?

The sun in relation to God is not a foreign concept in biblical scripture. For example, Malachi 4:2 reads, “But unto you that fear my name shall the Sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings.” In this verse in Malachi, the “Sun of righteousness” has a dual meaning acknowledged by most Christians, understanding this verse as referring to Jesus Christ, the son of righteousness meaning the son of God.

Mesoamerican cultures had an influence in the American Southwest, as has been determined by the use of jade and turquoise in both locales.32 To the Hopis — a Southwestern Native American tribe — the sun is only the face through which their Creator, Taiowa or Tawa, stands behind and oversees his creation. This thinking is akin to what the Essenes in the Jewish community of Qumran believed with regard to the sun. Erwin Goodenough notes, “The Essenes addressed prayers to the sun. The figure, then, must be understood as being if not a representation of God for Jews at least a manifestation of Deity, a sign of Deity, and because of the potency to which the amulets attest, a symbol of Deity.”33

In the Old Testament, Psalm 84:11 clearly states, “The Lord God is a sun.” No Jew or Christian takes this literally, but as a symbol of God’s [Page 70]creative power that makes everything in this world work — there would be no life without the sun. In the New Testament, Jesus Christ is sometimes typified by the brightness of the sun. On top of a high mountain, Jesus “was transfigured before them [Peter, James and John]: and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as the light” (Matthew 17:2). On the road to Damascus the risen Christ appeared to Paul. He writes in Acts 26:13 “in the way a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun, shining round me and them which journeyed with me.” In Revelation 1:16, John also saw the risen Lord. He wrote, “And he had in his right hand seven stars: and out of his mouth went a sharp twoedged sword: and his countenance was as the sun shineth in his strength.”34 These visions incorporating the sun’s brightness are of course symbolic, reinforcing the concept that the sun may be associated, and logically, with our Lord.

Returning to Mesoamerica, there are a few legends we need to consider in relation to the sun and deity. Allen Christenson’s work on the modern-day traditions of the Maya concerning Christ representing [Page 71]the sun is revealing. He writes, “Among the Maya, the resurrection of Christ following his crucifixion is often equated with the rising of the sun, similar to the apotheosis of Jun Junapu [the Maize God] as the sun.”35 The Maize God has numerous depictions of his resurrection from a turtle, the earth being represented by a turtle among the Maya).36

Figure 6: The resurrection of Hun Nal Ye, the Maize God, from a turtle carapace, painted on a Maya vessel (drawing by D. Wirth)

The maize seed was considered dead — when it sprang to life it was viewed as having been reborn or resurrected, thus, the prominence of the Maize God among the Maya.

The Maya monuments in Guatemala considered below are from the Late Classic period [ad 600–900], and display complex scenes often involving a person interacting with a supernatural being. Monument 1 from El Castello in the Cotzumalhuapa region depicts a man with a speech scroll coming from the individual talking with the sun deity.

The man is climbing what appears to be a rope, but in actuality this motif is the edge of an open-mouthed reptilian monster, whose teeth act as stairs. The deity sitting above in the opened mouth is most definitely the sun, as is determined by the sunburst around him. These monuments are considered to be done in a narrative style, like Stela 5, referred to as the “Tree of Life” stone by some Latter-day Saints, at Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico,37 which contains no hieroglyphic text giving a clue to the monument’s intended message. They simply tell a story in picture form.

[Page 72]Monument 3 from Bilbao, again from the Cotzumalhuapa region, depicts the descending sun deity above a man, who looks up at this bright supernatural personage. Another, Monument 6, also from Bilbao, has an identical theme. There are many other monuments of descending gods without the sun deity — they are all considered depictions of supernatural entities, and show the relevance of their association of divine beings communicating with men.

Tulum, a site in the Yucatan, dates to about the end of the 15th century, shortly before the Spanish Conquest. The idea of descending gods appear at Tulum roughly five hundred to eight hundred years later than those on the Cotzumalhuapa monuments. At Tulum there is a building called The Temple of the Descending God, and there are several depictions of this deity in stucco. There is also a painting in Mural 2 from Structure 16, called the Temple of the Frescoes, with the descending god.

Figure 8: Descending god from Mural 2, Structure 16 at Tulum, Yucatan, Mexico (drawn by Felipe Dávalos)

Some LDS tour guides say this is evidence of Christ’s visit to Mesoamerica, which may be a bit presumptuous, since we simply do not have concrete evidence for this assumption as stated earlier. However, we have to wonder if these depictions of descending gods may derive from a long-held tradition of supernatural beings visiting earth.

Several ceramic containers from the Yucatan dating from ad 1200–1400 depict descending or diving gods, as they are sometimes called by archaeologists.

Figure 9: Ceramic diving god container wearing a bird headdress, housed at the U.S. Library of Congress

[Page 73]Most have a bird headdress, representative of their high god. The answer as to who this god may represent is varied: The Maize God, Itzamna, or Quetzalcoatl. We do not really know. Such depictions of a deity descending are associated with sacrifice; however, many of them have been interpreted as a symbol of the sun, fertility, and maize.38

Bancroft in his Native Races written in the nineteenth century noted, “After the mysterious departure of Cukulcan, the Maya Quetzalcoatl, from Yucatan, the people, convinced that he had gone to the abode of the gods, deified him, and built temples and instituted feasts in his honor.”39 Bancroft is writing about the people in Mani, Yucatan. They still remembered their culture hero, Kukulcan or Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, whose life his followers patterned after their god Quetzalcoatl for many generations to come.

The people of Mani had a feast commemorating this culture hero. Continuing with Bancroft, he writes, “They said, and confidently believed, that Cukulcan descended from heaven on the last day of the feast and received personally the gifts which were presented to [Page 74]him. This festival was called chic kaban.”40 The ceremony in honor of Kukulcan was observed all over Yucatan until ad 1341 and especially at Mani.41 The culture hero Kukulcan, a.k.a. Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, lived approximately in the 10th or 11th century. No one really knows the exact dates, but much has been written of this leader that was passed down orally from one generation to the next.42

In summary, we have seen there are many theophanies in scripture describing celestial visitations accompanied with clouds, or even a voice penetrating through clouds to selected people on the earth. Some of these people were righteous, others not. Creating clouds of light or clouds of darkness were determined by the Lord with regard to the nature of the onlookers.

Discussing the differences associated with these clouds in the scriptures is an added insight that I found while researching this topic. Differentiating between clouds of light and clouds of darkness is a phenomenon that cannot be determined at present existing in thought among Mesoamerican cultures. However, the presence of clouds in general among the Maya refers to the celestial realms where the gods live. With or without clouds, scenarios were depicted in art of celestial visitations among the Olmec circa 500–400 bc, to the 15th century by the Maya. Even today, the Maya believe in descending ancestors and deities. Due to their ancient mythological traditions, they chose to associate Christ with the sun,43 and as we have seen, examples were described showing visitations of a sun deity.

Did some Mesoamerican cultures have a tradition of viewing supernatural beings since they were aware of their mythological beliefs deriving from stories we see recorded in the Book of Mormon? We do not know, but, saying this with caution, it may be plausible as has been demonstrated here.[Page 75]

Figure Credit Details

Figure 4. Drawing by D. Wirth after drawing by Keith Henderson from The Conquest of Mexico, by W. H. Prescott, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1922, I: 185.

Figure 5. Drawing by D. Wirth after drawing by Ian Graham, Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, vol. 3, part I, Yaxchilan. With Eric von Euw. Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1977, p. 39.

Figure 8. Drawn by Felipe Dávalos in Arthur G. Miller, On the Edge of the Sea: Mural Painting at Tancab-Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico, Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1982, pl. 37). This illustration was scanned from Gabrielle Vail and Christine Hernández, Re-Creating Primordial Time: Foundation Rituals and Mythology in the Postclassic Maya Codices, Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2013, 130 Fig. 4.16.

Figure 9. U.S. Library of Congress, J. Kislak Collection. Photograph by Justin Kerr, No. 6243.

1 The term “Mesoamerica” comprises the areas of southern Mexico and Central America. See Mark A. Wright, “Heartland as Hinterland: The Mesoamerican Core and North American Periphery of Book of Mormon Geography,” paper presented at FAIR Conference, Provo, UT, 2013, http://www.fairmormon.org/perspectives/fair-conferences/2013-fair-conference/2013-heartland-as-hinterland-the-mesoamerican-core-and-north-american-periphery-of-book-of-mormon-geography; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City: Deseret, and Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, 2013); John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: Research Press: Foundation for Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1998); John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14/2 (2005): 38–49, 71–74.

2 David Freidel, Linda Schele, and Joy Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman’s Path (New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc., 1993), 152.

3 Aphrahat, Demonstration 5:21, in Daniel Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ (New York: The New Press, 2011), 39.

4 Margaret Barker, The Mother of the Lord, Vol. 1: The Lady in the Temple (New York and London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2012), 1:202.

5 “Cloud” in the scriptures will be in bold font for emphasis.

6 The “tables of stone” are the Ten Commandments, or the Law of Moses.

7 Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 549.

8 For example. John L. Sorenson, “Cultic Similarities between the Ancient Near East and Mesoamerica,” presented at the conference “ABC + 10,” held by the New England Antiquities Research Association, Waltham, Massachusetts, Nov. 1–3, 2002; Diane E. Wirth, Parallels: Mesoamerican and Ancient Middle Eastern Traditions (St. George, UT: Stonecliff Publishing, 2003).

9 Translated beings such as Enoch and his people and the Three Nephite disciples are “ministering angels.” Regarding translated beings, Joseph Smith taught, “Their habitation is that of the terrestrial order, and a place prepared for such characters.” See Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, compiled by Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1938, 1972), 170.

10 Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (New York: Random House, 1991), 1341.

11 Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 35–36.

12 Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 532–533.

13 “Research at Ceibal Challenges Two Prevailing Theories on How Maya Civilization Began,” in IMS Explorer 43/9, Institute of Maya Studies, an affiliate of the Miami Science Museum (September 2014): 2.

14 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 151.

15 William L. Fash, Scribes, Warriors and Kings: The City of Copán and the Ancient Maya (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1991), 122–123.

16 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 152.

17 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 152.

18 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 206.

19 Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Native Races, Vol. II (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co., 1883), 668.

20 Linton Satterthwaite, “Incense Burning at Piedras Negras,” in University of Pennsylvania, Museum Bulletin 11(4): 16–22, 1946.

21 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 190.

22 William H. Prescott, The Conquest of Mexico (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1922), I: 185, cited in Fanning the Sacred Flame: Mesoamerican Studies in honor of H. B. Nicholson, Matthew A. Boxt and Brian Dervin Dillon, eds. (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 2.

23 Diane E. Wirth, “Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ,” in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 4–15.

24 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 289.

25 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 208.

26 Mary Miller and Karl Taube, The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 150.

27 Quetzalcoatl has an English translation of “feathered serpent.”

28 Dennis Tedlock, translator, Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings (New York: Touchstone, 1985, 1996), 161.

29 Freidel, Schele, and Parker, Maya Cosmos, 291–292.

30 Allen J. Christenson, “Maya Harvest Festivals and the Book of Mormon,” in FARMS Review 3/1 (1991): 11–12.

31 Simon Martin and Nicolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 159.

32 The Hopi had a Parrot Clan. Parrots are technically called Macaws and were indigenous to the region of Central America. Jade, native to Mesoamerica, and turquoise to the American Southwest, were frequently traded.

33 Erwin R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988 Abridgment), 121.

34 See also Revelation 10:1.

35 Christenson, “Maya Harvest Festivals and the Book of Mormon,” 11.

36 Wirth, “Quetzalcoatl, the Maya Maize God, and Jesus Christ,” 7.

37 See V. Garth Norman, “Stela 5,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, gen ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 740–744.

38 MAYA, eds. Peter Schmidt, Mercedes de la Garza and Enrique Nalda (New York: Rizzoli, 1998), 619.

39 Bancroft, The Native Races, Vol. II: 699.

40 Bancroft, The Native Races, Vol. II:700.

41 Robert J. Sharer, The Ancient Maya, fifth edition (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1946–1994), 552.

42 See for example, H. B. Nicholson, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2001).

43 Louise M. Burkhart, Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 7.

Go here to see the 8 thoughts on ““Celestial Visits in the Scriptures, and a Plausible Mesoamerican Tradition”” or to comment on it.