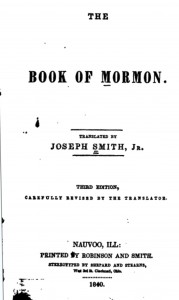

[Page 35]Abstract: The third edition of the Book of Mormon was stereotyped and printed in Cincinnati in 1840. The story of the Church’s printer, Ebenezer Robinson, accomplishing this mission has been available since 1883. What has remained a mystery is exactly where in Cincinnati this event took place; there is no plaque marking the spot, no walking tour pamphlet, no previous images, and its history contains conflicting documentation. This article will attempt to untangle the mystery by using old descriptions, maps of the area, and images. I also honor the printer, Edwin Shepard, whose metal and ink made this edition a reality.

In early 1839, the Mormons, under official government threat of extermination, were expelled from the State of Missouri, leaving homes and property behind, which were confiscated without remuneration “to defray the expenses of the war.”1 The Saints had very little money when they started to build a new life on a swampy eastern bank of the Mississippi River. They settled in Commerce, Illinois, which seems an ironic misnomer for the town, considering little business was conducted in the area.2 Joseph Smith, intent on transforming this small parcel of swampy land into a safe place for the Saints to live and prosper, renamed the city Nauvoo, which he interpreted as “a beautiful location, a place of rest.”3

[Page 36]The demand for Church publications including copies of the Book of Mormon increased as Saints continued to settle in Nauvoo, but the inventory of copies had been totally depleted.4 In the early 1830s when the Saints were headquartered in Kirtland, Ohio, the Prophet Joseph Smith’s youngest brother, Don Carlos, and recent convert, Ebenezer Robinson, both printers, were employed in the Church’s printing operations. They worked just behind the northwest corner of the Kirtland Temple in the Church’s printing office located on the second floor of a separate multipurpose wood-frame building. Here between three and five thousand5 copies of the second edition of the Book of Mormon were printed in the winter of 1836–1837.6 A year later on January 16, 1838, a suspected arson fire destroyed the printing office as well as some of the inventory of the newly-printed second edition.7

When the Saints removed to Far West, Missouri, in early 1838, a new printing press was procured. During the violent clashes between the Saints and the Missourians in 1838, precautions were taken to hide and safeguard the printing press. Along with the press, the type was boxed and buried in the ground, and a haystack was placed over the cache. The press and type were later retrieved and brought to Nauvoo, but some of the type had corroded and had to be replaced.8

Church leaders in Nauvoo were unable to raise any money from its destitute members, who were struggling just to meet life’s basic necessities.9 Ebenezer Robinson felt a personal responsibility to get the Book of Mormon again into circulation. He recorded that as he was [Page 37]walking to the printing office in Nauvoo in May 1840, he received “a manifestation from the Lord, such an one as I never received before or since. It seemed that a ball of fire came down from above and striking the top of my head passed down into my heart, and told me, in plain and distinct language, what course I should pursue and I could get the Book of Mormon stereotyped and printed.”10

“[I was] to go to Cincinnati, and as the plates were being stereotyped hire a press and get the books struck off form by form, so that when the last set of plates was done, the books should be ready for delivery. … I was to send circulars to the different branches, that for every hundred dollars they would send us, we would send them one hundred and ten copies of the Book of Mormon, and in that same ratio throughout, God promised [me] that by the time we got the books out we would have enough to pay for them; at least we would be able to meet the expense that way. The matter was so plain to me that I knew all about it. From that minute I knew just what to do.”11Don Carlos and Ebenezer were able to negotiate a deal for $145 from one brother, but even though they advertised in the Times and Seasons to get seed money for the project, they failed in raising any additional funds. Despite not being fully funded for the endeavor, Robinson told Don Carlos, “Yes, I will go to Cincinnati, but I will not come home until the Book of Mormon is stereotyped.”

Stereotyping is the fabrication of permanent metal plates from molds of typeset pages, so the plates may be used again for printing at a later time without having to typeset anew each page. Accomplishing this mission to Cincinnati Robinson said “was as fire shut up in my bones, [Page 38]both day and night”; he could not rest until he saw the work through to completion.12

The Prophet agreed to the project and then sat down with Robinson to “carefully revise” a copy of the second edition of the Book of Mormon (1837), which Robinson would take to Cincinnati. During the process of revision, the Prophet referred to the original manuscript. It appears it was the last time the Prophet corrected the Book of Mormon prior to a printing, making the resultant 1840 third edition an important source for the Church’s 1981 printed edition, which Latter-day Saints use today.13

Stereotyping and Printing the New Edition

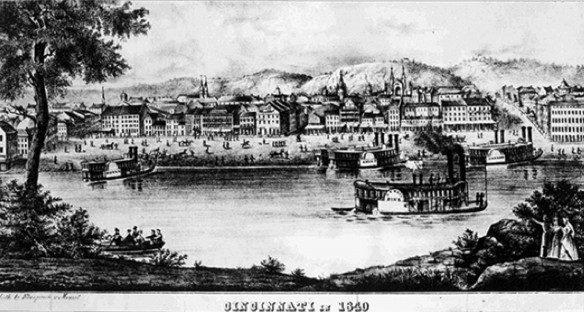

Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1840 was the fastest growing big city in America.14 Though on the frontier, the fair “Queen City of the West” got its moniker for its nineteenth-century “order, enterprise, public spirit, and liberality.”15 At 46,000 inhabitants, the city ranked sixth in U.S. population, exceeded only by the immigration port cities of New York, Baltimore, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Boston, respectively.16 By 1850, Cincinnati was recognized as the nation’s second largest industrial hub, and six years later ranked fourth in printing and publishing output.17

On June 18, Robinson boarded the packet steamboat18 Brazil and headed down the Mississippi River to St. Louis then up the Ohio River to Cincinnati. Robinson lost a portion of the money to con men at the [Page 39]riverfront in St. Louis, but he actually considered it a blessing; he felt he learned a lesson to focus more intently on his sacred mission and not be distracted from it again.19

When he reached Cincinnati, Robinson sought out a print shop but felt uncomfortable in the first establishment he visited. After getting a bid for the work, he asked if there were another stereotype foundry in town. He was told he could go to a print foundry, Glezen & Shepard, in Bank Alley off Third Street. Robinson said, “I felt in an instant that that was the place for me to apply to,” whereupon he left and was able to locate the other foundry.20

[Page 40]“As I entered the office, I saw three gentlemen standing by the desk, in conversation,” recounted Robinson in 1889. “I asked if Messrs. Gleason and Shepherd were in. A gentleman stepped forward and said, ‘My name is [Glezen].’ I said, ‘I have come to get the Book of Mormon stereotyped.’” Eben Knight Glezen was in the process of leaving the partnership, which caused Edwin Shepard to step forward as the new lead proprietor declaring, “When that book is stereotyped I am the man to stereotype it.”21 The third man Robinson observed could very likely have been Shepard’s new partner, George Sullivan Stearns.22Shepard calculated the cost of stereotyping at $550, and Robinson responded with an offer to pay $100 up front, $250 during the three months it would take Shepard to do the job, and the remaining $200 after the job was complete. In addition, Robinson offered to provide sweat equity, mainly proofing the plates at 25 cents an hour. Both parties agreed to the arrangement. A contract was signed, and three type [Page 41]compositors began work on the third edition within twenty-four hours.23

Robinson also decided that as each set of sixteen proofed plates were finished, he would have two thousand “signature”24 sheets of those sixteen pages printed and have the sheets folded and bound while waiting for the next set of sixteen plates to be stereotyped, enabling him to have two thousand finished copies of the Book of Mormon by the time he would return to Nauvoo.25

After purchasing paper,26 ink, and binding supplies, he was under contract for a total amount of $1,050. Robinson, having only six and three-quarter cents — “an old-fashioned Spanish sixpence” — left in his pocket, found room and board on credit from one of the firm’s workers. Robinson anxiously waited several weeks [Page 42]before any funds from Nauvoo began to arrive.27 “I confess that for a time,” Robinson said, “viewed from a worldly standpoint, it looked quite gloomy, but I never for a moment lost faith in the final success, or literal fulfillment of the previous promise of the Lord made to me in Nauvoo.”28

Indeed, Robinson was successful. The job was finished in October 1840, and Robinson was able to pay for all the contracted work and supplies before the bills came due. One thousand copies were mailed to those who had pre-ordered, and the remaining one thousand were shipped from Cincinnati to Nauvoo. Upon his own return to Nauvoo that month, Robinson gave possession of the stereotype plates to Joseph Smith.29

By early 1841, all two thousand “Cincinnati” copies of the third edition of the Book of Mormon had been sold. Robinson and Don Carlos had received permission from the Prophet in December 1840 to print additional copies from the stereotype plates, this time in Nauvoo. Several hundred books were printed before the April 1841 conference to meet projected demand by the conference goers, with later printings completed to meet demand until reaching or possibly exceeding the authorized limit.30

Where in Cincinnati was Shepard & Stearns Located?

Today, without some considerable research, a person would have a hard time trying to locate exactly where in Cincinnati the third edition of the Book of Mormon was contracted, stereotyped, and printed. The buildings in which these events took place no longer stand, and neither do the buildings that had surrounded them. Complicating matters are changes in the location of points of reference such as the post office, the Masonic temple, the print shop itself, and changes in street names. These challenges are compounded by lags in the updates to Cincinnati city directories and maps. Unlike the E. B. Grandin print shop, Grandin’s own gravesite in Palmyra, New York, or the plaque that notes the location of where the second edition of the Book of Mormon was published at the Church’s print shop on the Kirtland Temple grounds, there are no Church historical site markers honoring this important Church event. Locating the site of the third edition printing took some sleuthing.

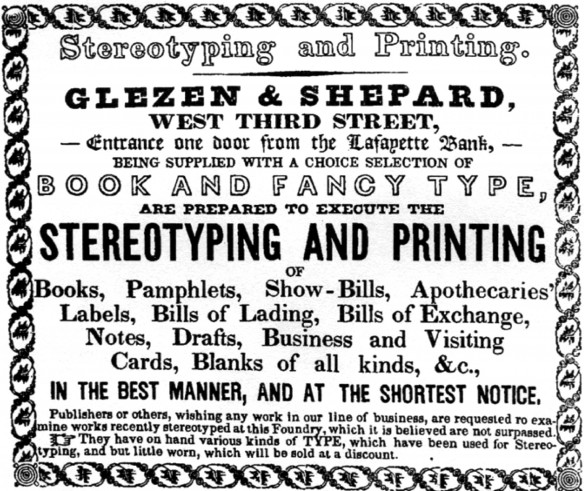

[Page 43]The Glezen & Shepard printing office in Cincinnati first opened in 1837 at 29 Pearl Street next to another printing establishment owned by Nathan G. Burgess at 27 Pearl Street (see footnote 20). An advertisement in Shaffer’s 1839–40 city directory, indicated that the Glezen & Shepard printing business had moved one block north to West Third St.31

Figure 5: Business Advertisement, Shaffer’s 1839–40 City Directory. Note the address on West Third Street, “one door from the Lafayette Bank.” Courtesy Cincinnati Library.

In the same city directory, the Glezen & Shepard office was described as being in the rear of Delafield & Burnet’s banking and exchange office,32 whose location is listed in that 1840 City Directory as being “Next door West of the La Fayette Bank.”33

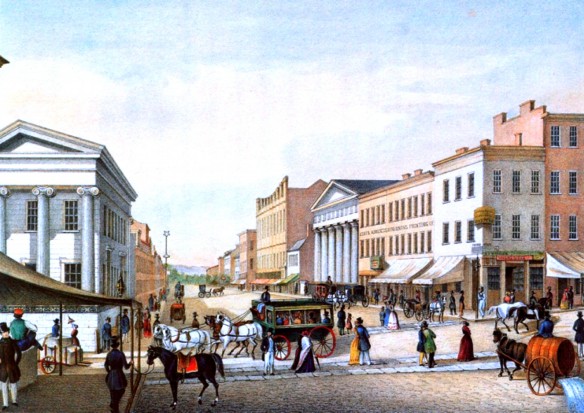

An 1849 lithograph by Ernst Schnicke depicts this location. The Lafayette-Franklin Bank is the colonnaded and classical Greek-gabled building in the center of Figure 6 on the north side of West Third Street. The bank building was erected in 1836 and existed until 1931. The castellated, fortress-like building beyond the bank is Cincinnati’s second Masonic temple, which was completed in December 1845. The smaller building, situated between the Lafayette-Franklin Bank and the Masonic temple, matches the location description of Delafield & Burnet/Glezen & Shepard in 1840.

Figure 6: Third Street between Main and Vine, ca. 1850. Courtesy of the Cincinnati History Library and Archives at the Cincinnati Museum Center.

[Page 44]The building in question was the first Masonic temple structure in Cincinnati. It was erected due in large part to the efforts of Mason and Assistant Postmaster Elam Potter Langdon.34 The two-story brick building fronted Third Street for fifty-six feet. The Masons used the second floor as its first lodge from December 27, 1824, to December 1845,35 and the Cincinnati Post Office occupied the first floor from 1824–1836. This is why Masonic Alley was also known as Post Office Alley. The building existed at least until 1849 and possibly as late as 1858 when a third Masonic temple replaced both the first and second temple buildings, consuming all of the two-hundred-foot frontage on Third Street between Walnut and Bank Alley.

[Page 45]In short, since this site was one door west of the Lafayette Bank in 1839–40 and Delafield & Burnet banking occupied the former post office space on the first floor,36 the location of Glezen & Shepard can now be pinpointed: it was the annex37 in Masonic/Post Office/Bank Alley38 behind Delafield & Burnet’s. Here the contract for stereotyping and [Page 46]printing the third edition of the Book of Mormon was signed, and the project was started.39 Though the printing office was in Bank Alley, it used West Third Street as its official address, as seen in the Figure 5 directory ad.

Glezen was on his way out of the partnership the day Robinson arrived,40 and only by means of the 1842 city directory do we know that Shepard moved the business into another building on the south side of West Third Street “opposite the Post Office.” It is not known if Shepard & Stearns moved during the printing of the third edition or if the move from Bank Alley happened after the book printing was completed in October 1840. The Title Page of the third edition (Figure 4) indicates, either: (1) Shepard continued to use the usual West Third Street address for the Bank Alley office, or (2) Shepard & Stearns had already moved by the time the title page was printed.41 Notwithstanding the actual print shop location between June 1840 and November 1841, mail could find [Page 47]its way to Shepard & Stearns simply by using West Third Street as an address.42

![Figure 8: [Third] Masonic Temple, 1859, chromolithograph. The First Temple was previously located just to the left of the colonnaded Lafayette-Franklin Bank building at right. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.](https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Figure-8.-Third-Masonic-Temple-584x440.jpg)

Figure 8: [Third] Masonic Temple, 1859, chromolithograph. The First Temple was previously located just to the left of the colonnaded Lafayette-Franklin Bank building at right. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. (Note this figure is located on page 46 of the printed text.)

Today the parking structure in Figure 9 occupies the spot where the Lafayette and Franklin Bank building stood between 1836 and 1931. The Scripps skyscraper to the left of the parking lot sits on the property where the first three Cincinnati Masonic temples stood on West Third Street. The narrow gap between the parking lot and the skyscraper is Berning Place, the former Bank Alley, where the entrance to Glezen & Shepard/Shepard & Stearns was located in 1840.

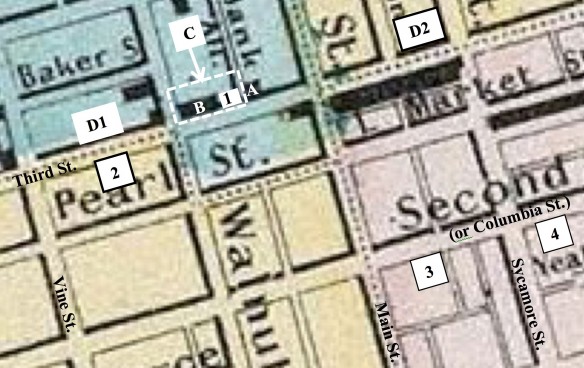

Figure 10: 1855 Colton Map of Cincinnati, Ohio, cartography by Joseph Hutchins Colton (George Washington Colton, Colton’s Atlas of the World Illustrating World and Political Geography, Vol. 1, New York: J. H. Colton & Co., 1855).

A: Lafayette-Franklin Bank building (1836–1931)

1: First Masonic building (used as such, 1824–1845), Post Office (1824–1836), Delafield & Burnet (1839–1840/41), and Glezen & Shepard/Shepard & Stearns (1839–1840/41)

B: Second Masonic building (1845–1858) and Post Office (June 24, 1845, to May 2, 1849)

C (Dashed white rectangle): Third Masonic Temple (1859–1928). Required razing of both 1 and B

D1 & D2: Post Office (1836–Nov. 1841; and Nov. 1841-June 24, 1845)

2: Shepard & Stearns and Shepard & Co. (1844–45)

3: Shepard & Co. (1846–1848) along with offices of Stearns & Co. as a printing ink supplier

4: Shepard’s stereotyping and printing office (1849) at 41 E. Second, then at 41 & 43 E. Second in 1850

[Page 48]Though the work of the third edition started in Bank Alley, Shepard & Stearns could have completed the stereotyping and printing of all or part of the two thousand “Cincinnati” copies of the third edition of the Book of Mormon in the shop on Bank Alley (map point 1) or at the new location (map point 2) shown in Figure 10. However, Ebenezer Robinson mentions nothing in his 1883 or 1889 memoirs about a printing office move while he was on his Cincinnati “printing mission.”

The City of Cincinnati purchased the land on Pearl Street and demolished all its buildings, so that the sunken Ft. Washington Way (I-71) could be extended through the downtown area. All buildings on the south side of Third Street and on the north side of Second Street were also razed. As a result, no nineteenth-century buildings stand there now (Figure 11; arrow approximates closely the location of Shepard & Stearns [Page 49]printing office between 1840/41–1843 and of Shepard & Co. in 1843–44). The Freedom Center, also called the Underground Railroad museum, is located in the middle of the photograph.

By 1845, Shepard & Co. moved to the south side of E. Second Street (or E. Columbia St.) at number 11 between Main and Sycamore.45 Then from 1847–1850, the print shop is listed at 41 E. Second Street between Sycamore and Broadway, still on the south side of Second Street.

Edwin Shepard died at the age of 38 on July 23, 1850, and was buried the following day in Spring Grove Cemetery, six miles north of Cincinnati. His death occurred as part of the 1849–1851 cholera epidemic, which claimed the lives of six to eight thousand residents of Cincinnati,46 just as Latter-day Saints had experienced elsewhere during that period. Since Shepard was not married and had no children, John Brooks Russell (managing editor47 of the Cincinnati Gazette, his [Page 50]landlord, business associate, and half-brother48 of Shepard’s former partner George Stearns) took possession of Shepard’s body and had it buried in Russell’s own family plot. There is no headstone on Edwin Shepard’s grave (Figure 12 at arrow).

If you search for Edwin Shepard’s last print shop location at 41 E. Second Street, you will end up at the home ballpark of Major League Baseball’s Cincinnati Reds.

Figure 13: Great American Ball Park, Cincinnati, Ohio. Courtesy of Google Images. (Note this figure is located on page 51 of the printed text.)

The Cincinnati Printing Mission

Locating the site of the third printing of the Book of Mormon is more than a trivial exercise revealing historical minutia. Its discovery adds a visual element to the testimony of Ebenezer Robinson in regard to the guiding hand the Lord provided for the printing of the Book of Mormon at a time when resources were scarce in the Church.

In June 1841, Robinson and Don Carlos Smith went to Cincinnati to buy printing supplies for the Church’s printing office in Nauvoo. They paid a visit to Edwin Shepard,49 and after settling their account, [Page 51]Robinson related that Shepard then arose and said: “‘Mr. Robinson, do you want to know what made me do as I did when you came here last summer, it was no business way, it was not what I saw in you, but what I felt here,’ putting his hand upon his heart.”50 Robinson continued:

“This voluntary statement of Mr. Shepherd’s afforded me great pleasure, as it was a practical illustration of the case with which the Lord can move upon the hearts of the children of men to assist in the accomplishment of his work and purposes. … From the foregoing experience, together with many other evidences that I have received of the truth of the divine origin of the Book of Mormon, I bear record that it is true, and that the promises and prophecies contained therein are being and will be fulfilled to the letter.”51

[Page 52]

Figure Credits

Figure 1: Ebenezer Robinson, ca. 1880s, unattributed photograph, courtesy of Community of Christ Archives, Independence, Missouri.

Figure 2: Cincinnati in 1840, lithograph by Klauprech & Menzel, 1839–40 Shaffer’s Cincinnati Directory, 1839, PDF Part 2, https://digital.cincinnatilibrary.org/digital/collection/p16998coll5/id/63487.

Figure 3: George Sullivan Stearns, [ca. 1870], unattributed, courtesy of the Wyoming [Ohio] Historical Society.

Figure 4: Title page, Book of Mormon, Third Edition Nauvoo, Ill.: Robinson and Smith, 1840, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Book_of_Mormon_(1840).djvu/page6-1024px-Book_of_Mormon_(1840).djvu.jpg.

Figure 5: Glezen & Shepard business advertisement, 1839–40 Shaffer’s Cincinnati directory, Cincinnati: Shaffer, 1839), PDF Part 1, 18, https://digital.cincinnatilibrary.org/digital/collection/p16998coll5/id/63487.

Figure 6: Third Street between Main and Vine, ca. 1850, color lithograph by Ernst Schnicke, published by Otto Onken, republished in Queen City Heritage, The Journal of The Cincinnati Historical Society 49/3 (Fall 1991): 24, courtesy of the Cincinnati History Library and Archives at the Cincinnati Museum Center.

Figure 7: Edward C. Skelton, P.M. and N. Rufus Moomaw, Jr. P.M., compilers, “History, First Temple (1824–1858),” in 175th Anniversary, Nova Caesarea Harmony Lodge No. 2 F&AM, Cincinnati: Cincinnati Masonic Lodge, 1966, courtesy of the Cincinnati Masonic Center Library.

Figure 8: [Third] Masonic Temple, 1859, chromolithographed and published by Middleton and Strobridge, Cincinnati, OH, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03138, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/pga.03138/.

Figure 9: Third Street at Berning Place, Cincinnati, Ohio, March 2014, Chris Miasnik.

Figure 10: George Washington Colton, 1855 Colton Map of Cincinnati, Ohio, cartography by Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800–1893), in Colton’s [Page 53]Atlas of the World Illustrating Physical and Political Geography, Vol. 1, New York: 1855, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1855_Colton_Plan_or_Map_of_Pittsburgh,_Pennsylvania_and_Cincinnati,_Ohio_-_Geographicus_-_PittsburghCincinnati-colton-1855.jpg.

Figure 11: Looking South across Third Street between Walnut and Vine, Cincinnati, Ohio, March 2014, Chris Miasnik.

Figure 12: Section 45, Lot 12, Spring Grove Cemetery, (where Edwin Shepard is buried), Jo Roth, findagrave.com volunteer, 6/25/2014 http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=79039232&PIpi=104152417.

Figure 13: Cincinnati Reds Great American Ballpark, Cincinnati, OH, Resource International Project Gallery, no attribution attainable, considered as Public Domain as found on Google Images, http://www.resourceinternational.com/ProjectGallery/cincinnatiredsgreatamericanballpark.aspx.

Disclaimer: I have made a good faith effort to locate and gain permission to use the images found herein. In the cases where I could not find a source, I have used the Creative Commons rules and the Copyright Term Table protocol for my article and considered the image to be in the Public Domain if the capture of the image was determined to be most likely pre-1923. If anyone finds that I have misused their image according to these terms, please hold me harmless and advise me. I will correct my error and give proper attribution.

1. Richard L. Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 367.

2. Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 384.

3. Glen M. Leonard, “Nauvoo,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007), accessed December 3, 2014, https://eom.byu.edu/index.php/Nauvoo.

4. “The persecutions in Missouri, and expelling the Church from the state, instead of having a tendency to destroy Mormonism, had the very opposite effect. An increased interest was manifest in the work, and calls were made for the Book of Mormon, but there were none on hand to supply demand.” Ebenezer Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks by Ebenezer Robinson (1816–1891),” Book of Abraham Project, accessed December 26, 2014, http://www.boap.org/LDS/Early-Saints/ERobinson.html.

5. Royal Skousen, “Book of Mormon Editions (1830–1981),” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007), accessed December 4, 2014, http://eom.byu.edu/index.php/Book_of_Mormon_Editions.

6. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

7. Kyle R. Walker, “‘As Fire Shut Up in My Bones’”: Ebenezer Robinson, Don Carlos Smith, and the 1840 Edition of the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Mormon History 36/1 (Winter 2010): 1–40.

8. Walker, “1840 Edition of the Book of Mormon,” 6–9.

9. “In the spring of 1840 consultation was held upon the subject of getting another edition of the Book of Mormon printed, to supply the demand, when, in view of our extreme poverty, consequent upon our so recently having been driven from our homes, the idea was abandoned, for want of the necessary funds to accomplish such a work.” Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

10. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

11. Ebenezer Robinson, “A Historical Reminiscence,” Saints Herald, March 1883.

12. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

13. Emily W. Jensen, “Publishing 1840 Book of Mormon No Easy Task,” Deseret News, May 22, 2009. Reporting on a presentation given by Kyle R. Walker at the Mormon Historical Association given on May 22, 2009, Jensen wrote that Walker noted, “It was the final edition of the Book of Mormon Joseph Smith would personally revise.”

14. Laura L. Chace, “Otto Onken: His Cincinnati Scenes,” Queen City Heritage, The Journal of the Cincinnati Historical Society (Fall 1991): 21 — 29.

15. Cincinnati Museum Center, Cincinnati Frequently Asked Questions, accessed August 15, 2014, http://library.cincymuseum.org/cincifaq.htm.

16. St. Louis did not become part of the top ten most populated cities until 1850 with Chicago joining the ranks in 1860; neither surpassed Cincinnati until 1870. Cincinnati’s last appearance in the top ten was in 1900 as number ten; Chicago was number two and St. Louis was number four that year. “Largest Cities in the United States by Population by Decade,” Wikipedia, accessed December 26, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Largest_cities_in_the_United_States_by_population_by_decade

17. Chace, “Otto Onken,” 21.

18. “Packets” were steamboats that had the primary duty to transport packages and mail, but they also took on passengers to convey from town to town along Jacksonian America’s inland waterways.

19. “At St. Louis, while the steamer was waiting for passengers and freight, I foolishly stepped into a mock auction store, when the auctioneer had up a fancy box filled with valuable articles … among which was a gold watch, or what the auctioneer claimed to be one. A young man present said he wanted an interest in the contents of the box, and if I would bid it off he would take half of it. I bid it up to $23, when of course I secured the prize, but just then I did not find my partner ready to take half. This took $23 from my already limited purse. I left that auction room, if not a better, I trust, a wiser man. Since writing the above sentence, the thought has occurred, to me that perhaps it was a good thing that it occurred, as it had a tendency to try my faith just that much more, and the sequel proved to me that the Lord is abundantly able and willing to provide means for the accomplishment of his purposes, when we follow his directions.” Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

20. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.” It is likely that the first print shop Robinson visited in early July 1840 was that of N. G. (Nathan G.) Burgess & Co. at 27 Pearl St. In 1837–38, Glezen & Shepard’s printing operation was at 29 Pearl St., right next door to Burgess. Walter Sutton, Western Book Trade, Cincinnati as a 19th-Century Publishing and Book Trade Center, 1796–1880 Directory of Cincinnati Publishers, Booksellers, and Members of Allied Trades (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1961).

21. Speaking of the book trade in its city, the Cincinnati Almanac for 1839 stated: “There are thirty printing offices; one type foundry; two stereotype foundries, (being the only establishments of the kind in the West).” (Ebenezer Knight Glezen, Picture of Cincinnati: The Cincinnati Almanac for 1839, Cincinnati: Glezen & Shepard, 1839, 70, emphasis added). For Ebenezer Robinson, coming to Cincinnati to get the Book of Mormon stereotyped could have been the easier part of his inspiration in Nauvoo. For Edwin Shepard to step forward and say he was the man for the job was likely an attempt to win business away from his only other stereotyping competition in the city and in the region.

22. 22 Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks”; Robinson, “A Historical Reminiscence, 147.

23. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

24. “Understanding and Working with Print Signatures,” DesignersInsights, accessed October 29, 2014, http://www.designersinsights.com/designer-resources/understanding-and-working-with-print.

25. 25 Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

26. Edwin Shepard took Robinson to Stationers’ Warehouse at 134 Main St. where they arranged to meet with Chauncey Shepard the next day about acquiring the printing paper that would be used for the third edition. It is not known if Edwin and Chauncey were related, but they were the only two in the 1840 city directory who spelled their last names the same way, both were from Connecticut, and both were members of the same allied trade (Robinson, “A Historical Reminiscence,” 147; David Henry Shaffer, Shaffer’s Cincinnati Directory for 1839–40, Cincinnati: Shaffer, 1839–40, 353).

27. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

28. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

29. Walker, “1840 Edition of the Book of Mormon,” 32.

30. Walker, “1840 Edition of the Book of Mormon,” 32–38.

31. Shaffer, Shaffer’s Cincinnati Directory, 18.

32. Shaffer, Shaffer’s Cincinnati Directory, 193.

33. Shaffer, Shaffer’s Cincinnati Directory, 59.

34. “Mr. Langdon was a member of the N. C. [Novae Caesarea] Harmony Lodge, No. 2, F. & A. M., and on its records occurs the following: ‘To the energy, sound judgment, constant attention and untiring exertions of our well remembered and zealous brother, Elam P. Langdon, was N. C. Harmony Lodge mainly indebted to the erection of the first Masonic hall [dedicated on Dec. 27, 1824] in this city, and to him are we indebted for years of a zealous and watchful care of the property interest and welfare of the lodge that has placed it in the front rank of prosperity.’” (Charles Frederic Goss, Cincinnati, The Queen City 1788–1912, Vol. 4, Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1912, 426).

35. Cincinnati Masonic Center, 175th Anniversary.

36. Glezen, Picture of Cincinnati, 56.

37. Charles Theodore Greve, Centennial History of Cincinnati and Representative Citizens, 2 vols. (Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company, 1904), vol. 1. In 1818, Assistant Postmaster Elam Potter Langdon started a tradition of establishing reading rooms at the post office where anyone could come and read the latest journals and newspapers, American and foreign, which arrived with the mail deliveries. As was the case with the most recently vacated post office location at 157 Main (corner of Main and Columbia/Second St.) where there was a reading room, this annex on Masonic/Post Office Alley was turned into the new Cincinnati Reading Room when the post office moved into office space on the ground floor of the newly-completed first Masonic building in December 1824. (Benjamin Drake, Cincinnati in 1826, Cincinnati: Morgan, Lodge, and Fisher, 1827, 44). Longtime postmaster Methodist Rev. William “Father” Burke (postmaster since 1814) and Langdon were leaders in Cincinnati Masonic circles, the fire department, Humane Society affairs (resuscitating “drowned” persons), and education. The fact that the Masonic hall, the post office, and the reading room were co-located made it easy for Langdon to provide facility support to all three.

38. The alley running from Third Street to Fourth Street between Main and Sycamore was designated Bank Alley in 1829 by the city of Cincinnati. Sometime between 1840 and 1842, the name of that alley was officially changed to Mayor’s Alley because of a new Mayor’s Office there, and by 1855 it was renamed one more time to Hammond Alley. Masonic Alley, known also as Post Office Alley up to 1836, was at least informally known as the “new” Bank Alley by 1840. By 1846, Masonic Alley formally had its name changed to Bank Alley. When Ebenezer Robinson came to Cincinnati in 1840, he most likely arrived on a cusp of Masonic Alley’s informal name change to Bank Alley probably due to it being next to the imposing Lafayette-Franklin Bank building. There is nothing that correlates to a print shop run by Glezen & Shepard being on the originally named Bank Alley between Main and Sycamore on East Third Street.

39. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

40. Robinson, “A Historical Reminiscence,” 146–47.

41. Charles Cist, Cincinnati Directory for 1842, Cincinnati: E. Morgan & Co., 1842, 277, 464.

42. It is also possible in relating his Cincinnati mission experience some forty-three and forty-nine years earlier in his 1883 and 1889 memoirs, Robinson used the name “Bank Alley” as a reference to the alley, as it was later known, to give his readers a then-current point of reference for the 1840 location of the Glezen & Shepard printing office.

43. C. E. Bailliere, The New World in 1859: Being the United States and Canada, Illustrated and Described, New York: Bailliere Brothers, 1859, 78–79.

44. Donald I. Crews, Cincinnati’s Freemasons, Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014, 45.

45. Walter Sutton, Western Book Trade, 337; R. P. Brooks, Cincinnati Business Directory for the Year 1846. Cincinnati: R. P. Brooks, 1846, 76).

46. Walter M. Daly, “The Black Cholera Comes to the Central Valley of America in the 19th Century–1832, 1849, and Later.” PMC — US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, accessed December 6, 2014, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2394684/; Ohio History Central, “Cholera Epidemics,” Ohio History Connection, accessed December 6, 2014, http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Cholera_Epidemics?rec=487.

47. Greve, Centennial History of Cincinnati, 797.

48. Abram English Brown, Genealogy of Bedford Old Families. Bedford, MA: By author, 1894, 33-36.

49. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.” The printing of the third edition of the Book of Mormon (1840) was begun in a print shop in an alley off the north side of Third Street. Whether the work was completed there or at an eventual new location a block away on the south side of Third Street is not known; Robinson does not allude to any move by Shepard & Stearns between June 1840 and June 1841 in either of his memoirs of 1883 or 1889. I have found no other records specifically indicating a move during this time period, but such a move by Shepard & Stearns to the new location “opposite the Post Office” could certainly have taken place sometime before November 1841. Whether the move took place while the third edition was being produced between June and October 1840 or by the time Robinson and Don Carlos returned to Cincinnati in June 1841 has not been determined. All we know is where the process began: in Bank Alley off of Third Street.

50. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.”

51. Robinson, “Autobiographical Remarks.” Robinson also reported in his 1883 memoir that when he and Shepard had finished proofing all the sheets for the third edition, “Robinson asked Shepard what he thought of the book. Shepard responded, ‘Well, I will tell you. It is either a true book, or it is the greatest imposition that was ever palmed upon mortals.’ Robinson replied, ‘Mr. Shepard, it is a true book.’” Robinson, “A Historical Reminiscence,” 147.

![Figure 3: George Sullivan Stearns, ca. 1870. Courtesy of the Wyoming [Ohio] Historical Society.](https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Figure-3.-George-Sullivan-Stearns-237x300.jpg)

Go here to see the 16 thoughts on ““Where in Cincinnati Was the Third Edition of the Book of Mormon Printed?”” or to comment on it.