[Page 159]Abstract: Joseph Smith taught that the origins of modern temple ordinances go back beyond the foundation of the world.1 Even for believers, the claim that rites known anciently have been restored through revelation raises complex questions because we know that revelation almost never occurs in a vacuum. Rather, it comes most often through reflection on the impressions of immediate experience, confirmed and elaborated through subsequent study and prayer.2 Because Joseph Smith became a Mason not long before he began to introduce others to the Nauvoo endowment, some suppose that Masonry must have been the starting point for his inspiration on temple matters. The real story, however, is not so simple. Though the introduction of Freemasonry in Nauvoo helped prepare the Saints for the endowment — both familiarizing them with elements they would later encounter in the Nauvoo temple and providing a blessing to them in its own right — an analysis of the historical record provides evidence that significant components of priesthood and temple doctrines, authority, and ordinances were revealed to the Prophet during the course of his early ministry, long before he got to Nauvoo. Further, many aspects of Latter-day Saint temple worship are well attested in the Bible and elsewhere in antiquity. In the minds of early Mormons, what seems to have distinguished authentic temple worship from the many scattered remnants that could be found elsewhere was the divine authority of the priesthood through which these ordinances had been restored and could now be administered in their fulness. Coupled with the restoration of the ordinances themselves is the rich flow of modern revelation that clothes them with glorious meanings. Of course, temple ordinances — like all divine communication — must be adapted to different times, cultures, and practical circumstances. Happily, since the time of Joseph Smith, necessary alterations of the ordinances have been directed by the same authority that first restored them in our day.

Joseph Smith’s Encounters with Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organization that emphasizes the use of formal ritual to teach what has been termed “a beautiful system of [Page 160]morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.”3 While the historic roots of the movement go back to at least the late 1300s within professional brotherhoods for Christian stonemasons in Scotland and England (operative Masons), the institutions and practices of modern Freemasonry are usually traced to the early eighteenth century — after the organization had opened its doors to others who had become interested in its ideas (speculative Masons).4 Despite Freemasonry’s relatively late origins, many of its teachings and ritual components draw on ideas from the Bible, early Christianity, and other ancient sources. As it evolved, the movement was also influenced by the ideals of enlightenment philosophy. In America, Freemasonry enjoyed rapid growth, especially in some periods of the nineteenth century, attracting a large number of citizens from all walks of life.5

Joseph Smith’s first encounters with Freemasonry occurred long before he came to Nauvoo. Indeed, it may be said that the Prophet, like many Americans of his era, “grew up around Masonry. His older brother Hyrum … was a Mason in the 1820s, as were many of the Smiths’ neighbors … To not be at least dimly aware of Masonry in western New York in the middle- to late-1820s was impossible.”6

That said, exactly what Joseph Smith knew about the specifics of the rituals of Freemasonry and when he came to know these details is a debated question. A ready source of information about Masonry for the young Prophet would have been the exposés of the anti-Masonic movement, whose epicenter was not far from the Smith home. He must have discussed Masonic ideas and controversies with his contemporaries. Though evidence of Masonic language and ideas in the Book of Mormon and the book of Moses is generally unconvincing, descriptions of some practices from the Kirtland School of the Prophets seem to recall Masonic ritual patterns (e.g., D&C 88:128ff.).7

Apart from whatever attraction the Prophet may have had to the rituals of Freemasonry, it seems from current evidence that he took little personal interest in Masonry as an institution until the Illinois period.8 Joseph Smith’s efforts to establish a Masonic Lodge in Nauvoo seem to have begun in November 1839,9 when he became personally acquainted with Judge James Adams. The judge was a prominent citizen of Springfield, Worshipful Master of the Springfield Lodge when it was founded in October 1839, and Right Worshipful Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Illinois when it was established — not coincidentally — on April 6, 1840.10 By at least the fall of 1840, he had been baptized a member of the Church.11 Adams was one of the select group of Mormon Masons who received the endowment when it was first introduced on May 4, 1842.12

Figure 1. Rebuilt Nauvoo Masonic Hall. The top floor was reserved specifically for Masonic activities, while the remainder of the building was used for a variety of other community events and gatherings. (Photograph courtesy of Sandi Christensen)

[Page 161]Glen M. Leonard13 observes that, through his Masonic friends and family, Joseph Smith “would have understood that Freemasonry held values cherished by religious persons of every faith.” However, this is only part of the picture. Statements by Joseph Smith and early Saints provide evidence of their belief “that the endowment and Freemasonry in part emanated from the same ancient spring” and that at least some similarities could be thought of “as remnants from an ancient original.”14 Benjamin Johnson, an intimate of the Prophet, said that he was told by him that “Freemasonry, as at present, was the apostate endowments, as sectarian religion was the apostate religion”15 — and thus, as Terryl Givens sees it, “not to be discarded wholesale.”16 According to a later statement by Elder Franklin D. Richards, Joseph Smith “was aware that there were some things about Masonry which had come down from the beginning, and he desired to know what they were, hence the lodge” was established in Nauvoo.17

The Masonic Lodge in Nauvoo

Evidence suggests that Joseph Smith encouraged Nauvoo Masonry at least in part to help those who would later receive temple ordinances. For instance, Joseph Fielding, an endowed member of the Church who joined Freemasonry in Nauvoo, said: “Many have joined the Masonic institution. This seems to have been a stepping stone or preparation for something else, the true origin of Masonry” — i.e., in ancient priesthood ordinances.18

One aspect of this preparation apparently had to do with the general idea of respecting covenants of confidentiality. For example, Joseph Smith once told the Saints that “the reason we do not have the secrets of the Lord revealed unto us is because we do not keep them.”19 But as he later observed, ‘“The secret of Masonry is to keep a secret.”20 Joseph may have seen the secret-keeping of Masonry as a tool to prepare the Saints to respect their temple covenants.

[Page 162]In addition, the rituals of the Lodge enabled Mormon Masons to become familiar with symbols and forms they would later encounter in the Nauvoo temple. These included specific ritual terms, language, handclasps, and gestures as well as larger patterns such as those involving repetition and the use of questions and answers as an aid to teaching. Joseph Smith’s own exposure to Masonry no doubt led him to seek further revelation as he prepared to introduce the divine ordinances of Nauvoo temple worship.

Finally, although Freemasonry is not a religion and, in contrast to Latter-day Saint temple ordinances, does not claim saving power for its rites,21 threads relating to biblical themes of exaltation are evident in some Masonic rituals. For example, in the ceremonies of the Royal Arch degree of the York rite, candidates pass through a series of veils and eventually enter into the divine presence.22 In addition, Christian interpretations, like Salem Town’s decription of the “eighth degree,” tell of how the righteous will “be admitted within the veil of God’s presence, where they will become kings and priests before the throne of his glory for ever and ever.”23 Such language echoes New Testament teachings.24 Thus, apart from specific ritual language, forms, and symbols, a more general form of resemblance between Mormon temple ritual and certain Masonic degrees might be seen in the views they share about the ultimate potential of humankind.25

That said, none of the many contemporary Mormon Masons who remained faithful to the Prophet following their temple endowment expressed a concern that Joseph Smith had been untrue to his Masonic oaths by incorporating some Masonic elements into the endowment ceremony.26 Moreover, it appears that the oaths made in the Lodge were taken seriously by faithful Mormons, both before and after their endowment.27 Richard L. Bushman observes: “If Joseph thought of Freemasonry as degenerate priesthood, he did nothing to suppress his rival.”28 In support of Bushman’s claim, it should be noted that interest [Page 163]in Masonry did not suddenly disappear after the temple endowment was introduced. Rather, it continued in Nauvoo until the departure of the Saints in 1846.29

Significantly, Andrew F. Ehat notes how the contents of a letter from longtime Mason Heber C. Kimball to Parley P. Pratt on 17 June 1842 testify of:30

the Prophet’s ease in pointing out the relationship of the endowment to Freemasonry in what might otherwise have been considered a blatant adaptation of Freemasonry[. This] demonstrates the awe and respect Heber Kimball and the others had for what has been a troublesome point to informed … Latter-day Saints [in more recent times]. These Freemasons who received these blessings in May 1842 completely accepted Joseph Smith’s self-characterization as expressed in an 1844 discourse: “Did I build upon another man’s foundation, but my own? I have got all the truth [offered by the world] and an independent revelation in the bargain.”31

Endowed members saw the Nauvoo temple ordinances as something more than what they had experienced as part of Masonic ritual. Hyrum Smith, a longtime Mason, expressed the typical view of the Saints about the superlative nature of the temple blessings when he said: “I cannot make a comparison between the house of God and anything now in existence. Great things are to grow out of that house; there is a great and mighty power to grow out of it; there is an endowment; knowledge is power, we want knowledge.”32

In summary, Freemasonry in Nauvoo was both a stepping-stone to the endowment and a blessing to the Saints in its own right. Its philosophies were preached from the pulpit and helped to promote ideals based on the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man that were dear to Joseph Smith. Its influence could be felt in diverse areas ranging from art and architecture to social and institutional practices. Importantly, Joseph Smith’s exposure to Masonic ritual was no doubt a spur to further revelation as the Nauvoo temple ordinances took shape under his prophetic authority. But whatever suggestions may have come to Joseph Smith through his experience with Masonry, what he did with those suggestions through his prophetic gifts was seen by the Saints as transformative, not merely derivative.[Page 164]

Ancient Precedents for Modern Temple Rituals

A notable witness of the transformative nature of temple ordinances in our day was Hugh W. Nibley, a Brigham Young University professor and internationally respected scholar of ancient cultures. Speaking of his own endowment in 1927, he remembered: “I was very serious about it … And the words of the initiatory [part of the endowment] — I thought those were the most magnificent words I have ever heard spoken.”33 Admitting that his first visit to the temple had left him “in something of a daze,” his return to the temple after his mission was an overwhelming experience: “At that time I knew it was the real thing. Oh, boy, did I!”34

Nibley’s delight in knowing that the ordinances he received were the “real thing” was not only because he felt and understood the power of the temple personally but also because he recognized that many of the teachings and forms used in modern ordinances resonated with what he already knew about ancient temple worship. Nibley remained a devoted participant and student of the temple throughout his life. His writings drew on his extensive knowledge of the ancient world and illuminated many aspects of restored temple ordinances. Other Latter-day Saint scholars have also made notable contributions to temple studies.35

General Withdrawal of the Higher Priesthood

As mentioned before, Joseph Smith taught that temple ordinances had been available in their fulness to select individuals and families since the time of Adam and Eve.36 However, they often have been administered only in a partial form due to the unreadiness of the covenant people to receive more.37 In times of apostasy, the temple ordinances associated with the higher or Melchizedek Priesthood were almost totally withdrawn from the earth. Intriguingly, Jewish sources allude to things pertaining to Solomon’s Temple that were no longer present in the Second Temple.38

The revelations and translations of Joseph Smith are clear in their witness that earlier forms of such loss also occurred in Moses’ day. At first, the Lord expressed His intent to make the higher ordinances of the holy priesthood available to all of Israel.39 However, because of their rebellion, the higher priesthood, and its associated laws and ordinances, were instead generally withheld from the people.40

Some prophets and kings, however, did continue to receive the highest ordinances of the Melchizedek priesthood in later Old Testament times.41 The overall structure and many of the details of kingship rites in Israel can be found in the Bible, and analogous rituals were practiced [Page 165]elsewhere in the ancient Near East and in Egyptian tradition.42 Portions were imperfectly preserved in the teachings and rituals of some strands of second temple Judaism, in the practices of Copts and of Christians with Gnostic leanings, and in the liturgies of Christian Churches.43 Later, Christians with antiquarian interests incorporated and further developed selected aspects of ancient rituals as early Freemasonry took shape.

Although the concept of a “royal priesthood”44 expressed in a temple ordinance that confers the fulness of the priesthood might seem strange to many Christians today, the idea is perfectly consistent with ancient religious practices.45 For example, Nicolas Wyatt summarizes a wide range of evidence indicating “a broad continuity of culture”46 throughout the ancient Near East wherein the candidate for kingship underwent a ritual journey intended to confer a divine status as a son of God47 and allowing him “ex officio, direct access to the gods. All other priests were strictly deputies”48 to the divinely sanctioned priesthood office held by the king.

An Early Example of the Rites of Kingship

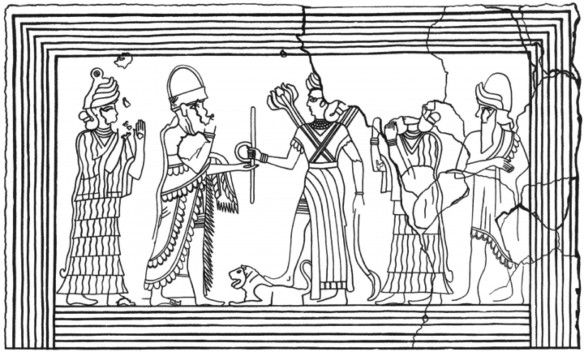

One remarkable example of kingship rites comes from the city of Mari in about 1800 bce.49 Among the foremost treasures of Mari is a painting on the palace walls that has come to be known as the “Investiture Panel,” which most scholars take to be a pictorial representation of the ritual in which kingship was renewed. Despite the fact that this ritual took place in Old Babylon, none of its primary themes will be unfamiliar to temple-going Latter-day Saints — nor to careful students of the Bible. Such resemblances may prove interesting for their bearing on the idea that corrupted versions of temple rites sometimes may have derived from authentic originals that predated the Old Testament as we now have it.

Though differing in some details, scholars of Mari are in general agreement that the areas in the ritual complex of the palace have been laid out so as to accommodate a ceremonial progression of the king and his entourage toward its innermost chambers. The sequence of movement from the more public to the most private portions of the palace complex would correspond to a stepwise movement from the outer edges of the Investiture Panel toward its center. Among the depictions of the Panel are what André Parrot called “undeniable biblical affinities” that he says “should neither be disregarded nor minimized.”50 Likewise, J. R. Porter, among others, has highlighted several features of the scenes that “strikingly recall details of the Genesis description of the Garden of Eden.”51

[Page 166]Creation. Although we know little directly about the details of Old Babylonian kingship rituals, it is certain that the later Babylonian New Year akītu festival always included a rehearsal of the creation story, Enuma Elish (“When on high…”), a story whose theological roots reach back long before the painting of the Mari Investiture Panel. In its broad outlines, this ritual text is an account of how Marduk achieved preeminence among the gods of the heavenly council through his victorious battles against the goddess Ti’amat and her allies, and the subsequent creation of the earth and of mankind as a prelude to the building of Marduk’s temple in Babylon. The epic ends with the conferral upon Marduk of fifty sacred titles, including the higher god Ea’s own name, accompanied with the declaration: “He is indeed even as I.” Seen in this light, one scholar has proposed a better title for Enuma Elish: “The Exaltation of Marduk.”

Garden with a Central Tree. Following the king’s ordeal and a recital of the events of the creation, it appears that the royal party would advance through a gardenlike open space. Babylonian gardens in palaces and temples typically featured fragrant trees with edible fruit that represented their concept of Paradise. A tree, either real or artificial, typically took the central position in such gardens, recalling the biblical account of the tree “in the midst” (literally “in the center”) of the Garden of Eden.

Sacrifice, Guardians, and the “Hand” Ceremony. A scene painted on the walls of the garden courtyard has been interpreted as representing the king leading a sacrificial procession into the next room of the ritual complex. Texts from Mari also tell us that the queen furnished sacrifices for the “Lady of the Palace,” presumably meaning Ishtar, the local divinity. As they continued their ritual progression, it appears that the party passed by guardians at the entrance to each of the private chambers. Scholars have noted interesting resemblances between the figures placed at meaningful locations in the Mari investiture panel, the cherubim in the Garden of Eden, and similar representations in the later Israelite tabernacle. They also conclude that at one or more points in the ceremony, the king would have touched or grasped the hand of a statue of Ishtar. The statue itself was not seen as a god, but rather as a physical representation that the god might inhabit during propitious times.

A Second Kind of Tree Supporting a Woven Partition. A second type of tree is depicted in the mural. It appears to have symbolized a doorpost. From archaeological evidence, it seems that a pair of such treelike posts might have provided supporting infrastructure for a partition made of ornamented woven material that screened off the most [Page 167]sacred chamber of the complex. The suggestion of such a screen recalls the kikkisu, a woven reed partition ritually used in temples, perhaps similar to the one through which the Mesopotamian flood hero received divine instruction. Ultimately, as one might infer from accounts such as Enuma Elish, the king would have passed by the guardians of this final gate and received the god’s own name and identity. By way of analogy to the function of the second type of tree in the Mari ritual, one might compare Egyptian, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions alluding to the Tree of Knowledge as a symbol for the veil of the temple sanctuary and the related themes of death and rebirth.

Figure 3. Culminating Rites of Royal Investiture. Line drawing of a detail from the upper central portion of the Mari Investiture Panel, Tel Hariri, Syria, ca. 1800-1760 bce (Image courtesy of Oxford University Press)

Culminating Rites. In the depiction of the culminating rites shown in Figure 3, the king, accompanied by a guardian with arms raised in the traditional attitude of prayer and worship, comes into the most sacred space of the palace where he would have received royal insignia from the hand of a representation of Ishtar, in the presence of other gods and divinized ancestors. The king’s hand is extended to receive these insignia while his arm is raised in a gesture of oath making. As also seen in biblical practice, the solemn nature of the oath was confirmed by touching the throat. Note that the Mesopotamian royal insignia of the rod and the coil as they were depicted here in 1800 bce, had a basic function of measurement similar to the square and compass in later times.

[Page 168]Summarizing the significance of ancient Babylonian temple ritual for Jews and Christians, John Walton observes, “[A]s much continuity as Christian theologians have developed between the religious ideas of preexilic Israel and those of Christianity, there is probably not as much common ground between them as there is between the religious ideas of Israel and the religious ideas of Babylon.”52 In particular, “the ideology of the temple is not noticeably different in Israel than it is in the ancient Near East. The difference is in the god, not in the way the temple functions in relation to the god.”53

Note that in Israelite practice, as witnessed in the examples of David and Solomon, the moment where the individual was actually made a king would not necessarily have been the time of his first anointing.54 The culminating anointing of the king corresponding to his definite investiture was, at least sometimes, preceded by a prior princely anointing. LeGrand Baker and Stephen Ricks describe “several incidents in the Old Testament where a prince was first anointed to become king, and later, after he had proven himself, was anointed again — this time as actual king.”55 Modern Latter-day Saints can compare this idea to the conditional promises they receive in association with ordinances and blessings, which are to be realized only through their continued faithfulness.

Were Such Rites Ever Intended for Others Besides the King?

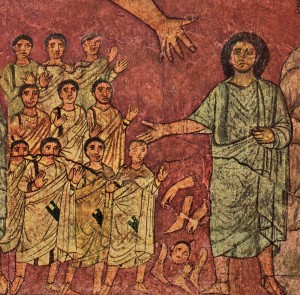

Figure 4. The Exaltation of Resurrected Israel, Dura Europos Synagogue, ca. 250. (Image courtesy of Yale University Press)

Although there is little indication in the Old Testament that Israelite kingship rituals were given to anyone besides the monarch, there is significant non-scriptural evidence from later times that analogous rites were made available to others. For example, findings at Qumran and Dura Europos suggest that, in at least some strands of Jewish tradition, priesthood rituals were seen as enabling members of the community, not just its ruler, to participate in a form of worship that brought them into the presence of God ritually.56 A hint of this tradition is evident in the account of God’s promise to Israel that, if they kept His covenant, not just a select few but all of them would have the privilege of becoming part of “a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation.”57

[Page 169]Going back to the first book of the Bible, some scholars have concluded that the statement that Adam and Eve were created in the “image of God”58 means that “each person bears the stamp of royalty.”59 Significantly, the promises implied in scripture (like the blessings of modern Latter-day Saint temples) are meant for Adam and Eve alike.60 In the New Testament, similar blessings, echoing temple themes and intended for the whole community of the faithful, are given in the book of Revelation.61 In the most pointed of these statements, the Savior declares: “To him that overcometh will I grant to sit with me in my throne, even as I also overcame, and am set down with my Father in his throne.”62

A Temple Tutorial in the Early Ministry of Joseph Smith

It appears that the Prophet learned much about temple ordinances through personal experiences with heavenly beings and revelations associated with his inspired translation of scripture. His revelations contain many unmistakable references to significant components of priesthood and temple doctrines, authority, and ordinances. Many of these date to the early 1830s, a decade or more before the Prophet began bestowing temple blessings on the Saints in Nauvoo. And given Joseph Smith’s reluctance to share the details of the most sacred events and doctrines publicly,63 it is certainly possible he received specific knowledge about some temple matters even earlier than can be now documented. These matters include: 1) the narrative backbone, clothing, and covenants of the modern temple endowment; 2) the sequence of blessings of the oath and covenant of the priesthood; and 3) priesthood keys and symbols expressed in keywords, names, signs, and tokens.

1. Endowment Narrative, Clothing, and Covenants

Scripture teaches that the greatest blessing one can receive is to enter the presence of God, knowing Him, receiving all that He has, and becoming His son or daughter in the fullest sense of the word.64 Note that individuals can enter the presence of God in one of two ways:

- in actuality, through a heavenly ascent or other divine encounter. In such an experience, individuals may be transfigured temporarily in order to receive a vision of eternity, take part in heavenly worship, participate in divine ordinances, or have conferred upon them specific blessings that are made sure by the voice of God Himself.65 In addition, followers of Christ look forward to an ultimate [Page 170]consummation of their aspirations by coming into the presence of the Father after death, there receiving the blessing of a permanent, glorious resurrection;

- ritually, through the ordinances of the Melchizedek priesthood found in the temple. For example, the LDS temple endowment depicts a figurative journey that brings the worshipper step-by-step into the presence of God.66

Significantly, the sequence of events described in accounts of heavenly ascent often resembles the same general pattern symbolized in temple ritual, so that reading scriptural accounts of heavenly ascent can help us make sense of temple ritual, and experiencing temple ritual can help us understand how to prepare for an eventual entrance into the presence of God.67 No doubt the allusions to priesthood ordinances often found within scriptural accounts of heavenly ascent are meant to serve a teaching purpose for attentive scripture readers. In brief, heavenly ascent can be understood as the “completion or fulfillment” of the “types and images” of earthly temple ritual.68

By 1830, Joseph Smith would have been familiar with many accounts of those who had actually encountered God face to face. Indeed, in his First Vision, he had experienced a visit of the Father and the Son while still a boy.69 In translating the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith learned the stories of other prophets who had seen the Lord, including the detailed account of how the heavenly veil was removed for the brother of Jared so that he could personally come to know the premortal Jesus Christ.70

From the point of view of temple ritual, in contrast to heavenly ascent, the most significant early tutoring that Joseph Smith received came in 1830 and 1831 with his translation of the early chapters of Genesis, canonized in LDS scripture as the book of Moses. The book of Moses makes significant additions to the Bible account that shed additional light on priesthood as well as on temple doctrines and ordinances. Significantly, these additions, mainly dealing with events that occurred after the Fall, also illustrate the same covenants introduced to the Saints more than a decade later in the Nauvoo temple endowment.71 Following a prologue in chapter 1 that describes a heavenly ascent by Moses, the remainder of the book of Moses provided the central narrative backbone and covenants of the Nauvoo temple endowment — an outline of the way in which the Saints could come into the presence of God ritually.

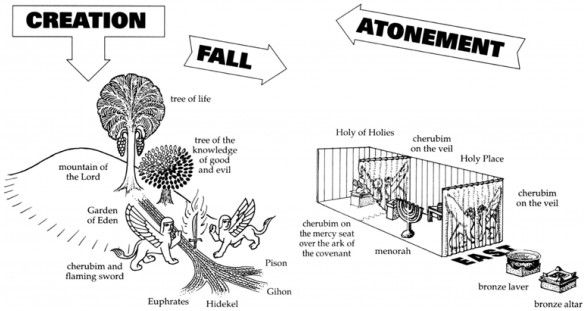

Figure 5. Sacred Topography of Eden and the Israelite Temple. (Illustration courtesy of Michael B. Lyon)

[Page 171]Parallels in the layout of the Garden of Eden and Israelite temples. Unlike the Masonic rituals that Joseph Smith would come to know,72 temple rites in the ancient Near East nearly always featured an explicit recital of the events of Creation.73 So it is with the Latter-day Saint temple endowment, which begins with the Creation story.74 The endowment continues with an account of the Fall of Adam and Eve75 and concludes with the story of their upward journey back to the presence of the Father.76

To appreciate how the stories told in the book of Moses relate to the temple, one must first understand how the layout of the Garden of Eden parallels that of Israelite temples. Each major feature of the Garden (e.g., the river, the cherubim, the Tree of Knowledge, the Tree of Life) corresponds to a similar symbol in the Israelite temple (e.g., the bronze laver, the cherubim, the veil,77 the menorah78).

Moreover, the course taken by the Israelite high priest through the temple can be seen as symbolizing the journey of the Fall of Adam and Eve in reverse (Figure 5). In other words, just as the route of Adam and Eve’s departure from Eden led them eastward past the cherubim with the flaming swords and out of the sacred garden into the mortal world, so in ancient times the high priest would return westward from the mortal world, past the consuming fire, the cleansing water, and the woven images of cherubim on the temple veils — and, finally, back into the presence of God. Likewise, in both the book of Moses and the modern temple endowment, the posterity of Adam and Eve trace the footsteps of their first parents — first as they are sent away from Eden, and later in their subsequent journey of return and reunion.

[Page 172]The story of Adam and Eve’s departure from and return to the sacred precincts of Paradise parallels a common three-part pattern in ancient Near Eastern writings: trouble at home, exile abroad, and happy homecoming.79 The pattern is as old as the Egyptian story of Sinuhe from 1800 bce80 and can be seen again in scriptural accounts of Israel’s apostasy and return81 as well as in the lives of biblical characters like Jacob.82 It can also be found in the Savior’s masterful parable of the Prodigal Son.83

This outline appears in modern literature as often as it did in those times.84 However, to the ancients it was more than a mere storytelling convention, since it reflected a sequence of events common in widespread ritual practices for priests and kings.85 More generally, it is the story of the plan of salvation in miniature as seen from the personal perspective. The life of Jesus Christ Himself also followed a similar pattern, though, unlike any ordinary mortal, He was without sin: “I came forth from the Father, and am come into the world: again, I leave the world, and go to the Father.”86

Temple clothing. As he translated the Bible in 1830–1833, Joseph Smith would have come across descriptions of temple clothing.87 For instance, he would have been familiar with the story of the fig-leaf apron and the coats of skins in the story of Adam and Eve88 and the clothing of the temple priests in Exodus 28, which represented the clothing of heavenly beings. It was reported in a late retrospection of an 1833 incident that the Prophet had seen Michael, the Archangel “several times,” “clothed in white from head to foot,” with a “peculiar cap, … a white robe, underclothing, and moccasins.”89 According to Hugh Nibley, the white undergarment represents “the proper preexistent glory of the wearer, while the [outer garment of the high priest] is the priesthood later added to it.”90 In Israelite temples, the high priest changed his clothing as he moved to areas of the temple that reflected differing degrees of sacredness. These changes in clothing mirror details of the nakedness and clothing worn by Adam and Eve in different parts of their garden sanctuary.91

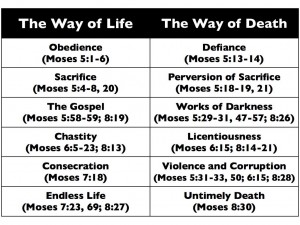

Temple covenants. The temple journey of return and reunion is made possible through obedience to covenants, coupled with the enabling power of the Atonement of Jesus Christ. As an Apostle, Elder Ezra Taft Benson outlined these covenants to a general audience as including “the law of obedience and sacrifice, the law of the gospel, the law of chastity, and the law of consecration.”92

Some LDS scholars have conjectured that an ancient book somewhat like the book of Moses may have been used as a foundation for temple narrative in former times.93 For instance, in the book of Moses, the story [Page 173]pauses from time to time and weaves in ritual acts like sacrifice; ordinances like baptism, washings, and the gift of the Holy Ghost; and themes relating to covenants like chastity and consecration. Mark Johnson has suggested that if an account of Enoch and his city of Zion was read in an ancient temple context, it would have been natural for members of an attending congregation to have covenanted to keep all things in common, with all they possess affirmed as belonging to the Lord.94

The illustrations of covenant-keeping and covenant-breaking provided in the book of Moses in 1830–1831 correspond to the sequence of covenants that was introduced in the Nauvoo temple more than a decade later, as shown in Figure 6. Significantly, John W. Welch found a similar pattern in his analysis of the Sermon on the Mount, in which the commandments “are not only the same as the main commandments always issued at the temple, but they appear largely in the same order.”95

What seems to be deliberate structuring of biblical accounts to highlight a sequence of covenants can also be found in the Hebrew Bible. For example, the eminent Bible scholar David Noel Freedman called attention to a specific pattern of covenant-breaking in the “Primary History” of the Old Testament. He concluded that this section of the biblical record was deliberately structured to reveal a sequence where each of the commandments was broken in specific order one by one.96

In summary, Joseph Smith’s translation of the book of Moses, in conjunction with his translation of other portions of the Bible, would have provided an extensive tutorial for the Prophet on temple-relevant stories, clothing, and covenants, long before the Nauvoo era.

2. The Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood

The temple endowment was only one part of the extended sequence of ordinances of exaltation that were revealed over time to the Prophet. Thus, comparisons of ancient or modern rituals that focus solely on the endowment miss a significant part of the overall picture.

[Page 174]As Joseph Smith continued his translation of the Old Testament beyond the chapters contained in the book of Moses, he learned of righteous individuals whose experiences provided a further tutorial about temple ordinances and the priesthood as they existed anciently. For example, between December 1830 and June 1831 Joseph Smith translated Old Testament chapters that described the plural marriages of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and the New Testament account of the Sadducees’ question about marriage in the resurrection.97 By at least 1835, Joseph Smith had begun teaching the principle of eternal marriage to others such as William W. Phelps, who was told that he and his wife were “certain to be one in the Lord throughout eternity” if they continued “faithful to the end.”98

Additional revelations and teachings of Joseph Smith, in conjunction with the ongoing work of Bible translation, elaborated on the stories and significance of righteous individuals such as Melchizedek and Elijah, explaining how the priesthood authority they held related to additional ordinances and blessings that could be given in the temple after one had already received the endowment and been sealed in eternal marriage covenants.99 For example, the blessings of the fulness of the Melchizedek Priesthood belong to one who is made a “king and a priest unto God, bearing rule, authority, and dominion under the Father.”100 [Page 175]Correspondingly, worthy women may receive the blessings of becoming queens and priestesses.101 It is fitting for these blessings to be associated with the name of Melchizedek, because he was the great “king of Salem” and “the priest of the most high God,”102 who gave the priesthood to Abraham.103 Later kings of Israel, as well as Jesus Christ Himself, were declared to be part of the “order of Melchizedek,”104 which was originally called “the Order of the Son of God.”105 Additional revelatory insights of the Prophet relating to ordinances received after the endowment and marriage sealing are especially evident in the changes he made in his translation of the Gospel of John and the Epistle to the Hebrews.106

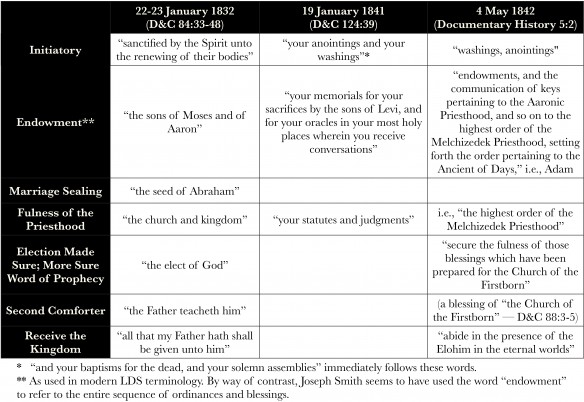

In summary, a search through the translations, revelations, and teachings of Joseph Smith reveals that an outline of ordinances and blessings, including those to be received following the temple endowment, was given to the Prophet early in his ministry. Indeed, by no later than 1835 the Lord had revealed to Joseph Smith doctrines and principles relating to what we now call the ordinances of the initiatory, endowment, eternal marriage, the fulness of the priesthood, and exaltation in the presence of the Father. An examination of the second and third columns of the table shown in Figure 7 reveals that the orderly sequence of these ordinances and blessings was summarized in D&C 124:39 on January 19, 1841, and again in a firsthand description of the events of May 4, 1842,107 the day the Prophet Joseph Smith began to administer these ordinances in the upper story of the Red Brick Store. Significantly, however, the most complete list of these ordinances and blessings, shown in the leftmost column, was given by revelation in 1832, a decade earlier.108

3. Priesthood Keys and Symbols109

When D&C 124 was revealed to the Prophet in 1841, he was told that “the keys of the holy priesthood” had been “kept hid from before the foundation of the world” and that they were soon to be revealed in the “ordinances” of the Nauvoo temple.110 However, at least some of these keys had been introduced to the Prophet long before. For instance, in December 1830, using language that resembled the later 1841 revelation, the Lord could say already to Joseph Smith that He had “given unto him the keys of the mystery of those things which have been sealed, even things which were from the foundation of the world.”111 This is temple language.112

Moreover, D&C 132:19 revealed that as a requirement for entering into “exaltation and glory” within the heavenly temple, the candidate for [Page 176]eternal life must be able to “pass by the angels, and the gods.” Elaborating details of this requirement, Brigham Young taught that in order to do so the Saints must be “able to give them the key words, the signs and tokens, pertaining to the Holy Priesthood.”113

Keywords and Names. “Keywords” have been associated with temples since very early times. In a temple context, the meaning of the term can be taken literally: the use of the appropriate keyword or words by a qualified worshipper, “unlocks” the gate for access to specific, secured areas of the sacred space.114

That said, whether or not the saving ordinances we perform in this life become effective in eternity depends as much on what we eventually become as on what we know. This is consistent with Old Testament examples of figures like Abraham, Sarah, and Jacob who received new names only after the Lord had tested their integrity.115 This also explains why names are so closely associated with keywords. Indeed, Joseph Smith taught that “The new name is the key word.”116

The importance of qualifying through worthiness and experience to take upon ourselves a sacred name is taught in ordinances like the sacrament, where we learn that we must “always remember” and be “willing to take upon [ourselves] the name of Jesus Christ.”117 Ultimately, however, we must not only be willing to take on the name of Jesus Christ but also become fully ready to do so if we are to receive every blessing outlined in the ordinances.118 To take upon oneself the name of Jesus Christ in actuality is to identify with Him to such a degree that we become one with Him in every aspect of saving knowledge and personal character.119

In 1829, Joseph Smith would have encountered this principle as he translated the words of King Benjamin, who understood why those who did not take upon themselves “the name of Christ” through obedience to the end their lives “must be called by some other name.”120 The theme of God’s sharing His own name with those who approach the final gate to enter His presence can also be found in the explanations of Facsimile 2 from the book of Abraham that date to sometime between 1835 and 1841.121 In Figure 7 of that facsimile, God is pictured as “sitting upon his throne, revealing through the heavens the grand Key-words of the Priesthood.” This concept is also found in Revelation 14:1, where we are told about those who would have the “Father’s name written in their foreheads.”

Signs and Tokens. The use of “signs” and “tokens” as symbols connected with covenants made in temples and used as aids in sacred teaching is [Page 177]an ancient practice. For example, the raised hand is a long-recognized sign of oath-taking,122 and the Ark of the Covenant in the Tabernacle contained various tangible “tokens of the covenant”123 relating to the priesthood, including the golden pot that had manna, Aaron’s rod that budded, and the tablets of the law.124

By way of analogy to a possible function of the items within the Ark of the Covenant — items that related to the higher priesthood125 — consider the Greek Eleusinian Mysteries,126 which endured over a period of nearly two thousand years. These rites were said to consist of legomena (= things recited), deiknymena (= things shown), and dromena (= things performed). A sacred casket contained the tokens of the god, which were used to teach initiates about the meaning of the rites. At the culmination of the process, the initiate was examined about his knowledge of these tokens. “Having passed the tests of the tokens and their passwords, … the initiate would have been admitted to the presence of the god.”127

In addition to a physical representation within sacred containers like the Ark of the Covenant, tokens could be expressed in the form of a handclasp, a symbol for unique individuality and joined unity that can be used both in tests of knowledge and identity as well as in acts of recognition and reunion.

Besides their use in tests of knowledge, clasped hands have been a prominent symbol of the marriage relationship since ancient times. This was also a symbol used by the Prophet Joseph Smith by at least 1835. For example, on November 24, 1835, Joseph Smith performed a marriage ceremony “by the authority of the everlasting priesthood.” He requested the bride and groom to “join hands” and then they entered into a “covenant” while the Prophet pronounced “the blessings that the Lord conferred upon Adam and Eve.”128

Sacred handclasps were also used in early Christian prayer circles. For example, according to the pseudepigraphal Acts of John,129 Jesus concluded His final instructions to the apostles with a choral prayer in which “he told [them] to form a circle, holding one another’s hands, and himself stood in the middle.”

The classical priestly posture of prayer with uplifted hands was known in the Old Testament130 and continued as a feature of Christian prayer in Joseph Smith’s day. Zebedee Coltrin recorded that at the Kirtland School of the Prophets on January 23, 1833, the participants were to “wash themselves,” “put on clean clothing” — in likeness of the Israelites at Mount Sinai131 — and then engage “in silent prayer, kneeling, with our hands uplifted each one praying in silence.”132 In this instance, [Page 178]the prayer with uplifted hands was followed by an appearance of the Father and the Son.

The Sacred Embrace. In ancient temple ritual, the gesture of the embrace could be seen as a stronger form of the symbolism represented in the handclasp. Whereas a handclasp can be used as a symbol of an unbreakable bond between two individuals, an embrace is an even more powerful symbol that can signify absolute unity and oneness between them.133

Notably, both the handclasp and the embrace can be used to represent not only mutual love and trust, but also a transfer of life and power from one individual to another. In what Willard Richards called “the sweetest sermon from Joseph he ever heard in his life,”134 the Prophet described a vision of the resurrection that included a handclasp and an embrace:135

So plain was the vision. I actually saw men, before they had ascended from the tomb, as though they were getting up slowly. They took each other by the hand, and it was, “My father and my son, my mother and my daughter, my brother and my sister.” When the voice calls for the dead to arise, suppose I am laid by the side of my father, what would be the first joy of my heart? Where is my father, my mother, my sister? They are by my side. I embrace them, and they me.

Joseph Smith’s words about the gesture of embrace in the resurrection recall similar symbolism in the stories of Elijah and Elisha, who each employed a similar ritual gesture as they raised a dead child back to life.136 The more detailed account of Elisha reads as follows:137

And he [Elisha] went up, and lay upon the child, and put his mouth upon his mouth, and his eyes upon his eyes, and his hands upon his hands: and he stretched himself upon the child; and the flesh of the child waxed warm.

Seeing anticipatory symbolism in this story, the Seder Eliyahu Rabbah specifically adds that the Messiah will be the very “Son of the Widow” whom Elijah raised from the dead. The threefold repetition of the act in the story of Elijah points to a ritual context, perhaps corresponding to a similar Mesopotamian procedure where the healer superimposed his body over that of the patient, head to head, hand to hand, foot to foot.138

Figure 8. Jacob Wrestling with the Angel. Chapter House, Salisbury Cathedral, England, 19th-century restoration of a 13th-century original (Photograph courtesy of Matthew B. Brown)

Those familiar with the Bible will also recall relevant temple symbolism in the story of Jacob. Speaking of Jacob’s dream of the heavenly ladder in Genesis 28, Elder Marion G. Romney said: “Jacob [Page 179]realized that the covenants he made with the Lord were the rungs on the ladder that he himself would have to climb in order to obtain the promised blessings — blessings that would entitle him to enter heaven and associate with the Lord.”139 Thus, in what may be a deliberate play on similar teachings in Freemasonry, the Prophet Joseph Smith correlated the “three principal rounds of Jacob’s ladder” with “the telestial, the terrestrial, and the celestial glories or kingdoms.”140 Later Jacob wrestled (or embraced, as this may also be understood141) an angel who, after a series of questions and answers in a place that Jacob named Peniel (Hebrew “face of God”), gave him a new name.142

Detecting True and False Heavenly Messengers. Of course, the keywords, names, signs, and tokens would be of no importance as symbols of authentication unless deception were a real possibility. In addition to their ancient use in sacred forms of prayer and as part of ritual and actual heavenly ascent, a knowledge of these things was important in detecting evil spirits.

When did Joseph Smith first learn about the keys by which he could distinguish true messengers from false ones? Arguably, on May 15, 1829 when John the Baptist restored the “keys of the ministering of angels” to him and Oliver Cowdery.143 During this experience “on the banks of the Susquehanna,” it seems that Satan appeared to deceive the Prophet and thwart the restoration of priesthood authority.144 As the Prophet later recorded, Michael (or Adam) then came to his aid, “detecting the devil when he appeared as an angel of light!”145 “Thus,” according to Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig Ostler, “the right to receive the ministrations of angels and the ability to discern true messengers of God from counterfeits came before the Church was organized.”146 Significantly, an account of how Moses recognized and successfully commanded Satan to depart by invoking the name of “the Only Begotten” was translated by Joseph Smith about one year after this experience.147

Bounded Flexibility in Adaptations of Temple Ritual

[Page 180]While, as Joseph Smith taught, the “order of the house of God”148 must remain unchanged, the Lord has permitted authorized Church leaders to make adaptations of the ordinances to meet the needs of different times, cultures, and practical circumstances. Latter-day Saints understand that the primary intent of temple ordinances is to teach and bless the participants, not to provide precise matches to texts, symbols, and modes of presentation from other times. Because this is so, we would expect to find Joseph Smith’s restored ritual deviating at times from the wording and symbolism of ancient ordinances in the interest of clarity and relevance to modern disciples. Similarly, we would expect various adaptations in the presentation of the ordinances to mirror changes in culture and practical circumstances.

Adaptations in the Wording and Symbolism of Ordinances

D&C 1:24 explicitly recognizes the need for bounded flexibility in adapting divine communication to accommodate mortal limitations, asserting that God always speaks to humans “in their weakness,” choosing a language of revelation that is “after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.” In this regard, Richard L. Bushman reminds us that:149

all sorts of cultural baggage of worldly culture, human culture, is loaded into the communications that we’re receiving from God. And there’s always going to be a filter, a screen, that’s going to obscure what God truly is and what He wants to communicate to us, because He’s dependent — He has to use the language we can understand.…

[Thus,] the vocabulary that the Lord uses to communicate through His prophets is not just “pure” or “biblical” or “religious” vocabulary, but whatever best serves His purpose, including Masonic terminology. [However,] what we must remember is that even though these languages are borrowed and bring cultural baggage with them, we revise that language, we make it our own.150 It soon assumes a Mormon, or we would say, perhaps, a more godly form because it is used in the context of other revelations and of all the practices that Mormons use. And that is particularly true … with the temple.

[Page 181]With respect to the temple, Samuel M. Brown151 has argued that Joseph Smith appropriated and “translated” selected elements of Freemasonry into the temple teachings and practices he introduced to the Saints.152 However, sometimes it may be more accurate to see the process by which revelation came to the Prophet in an inverse fashion. In other words, we might see the revelatory process, at least in some cases, not primarily as a “translation” of elements of Masonic ritual into Mormon temple ordinances, but rather as a “translation” of revealed truths — components of temple ordinances that Joseph Smith had previously encountered in his translation of the Bible and through his personal revelatory experiences — into words and actions that the Saints in Nauvoo could readily understand because their intuitions had already been primed by their exposure to the Bible and to Freemasonry.153

It should be no more a surprise to Latter-day Saints if some phrasing of the rites of Freemasonry parallel selected aspects of restored temple ordinances than the idea that wording similar to that of the King James Version was adopted in the English translation of scriptural passages from the Old Testament included on the Book of Mormon plates.154 In both cases, the use of elements already familiar to the early Saints would have served a pragmatic purpose, favoring their acceptance and understanding of specific aspects of the ancient teachings better than if a whole new and foreign textual or ritual vocabulary had been introduced.

As an instructive instance of change and continuity within the ordinances, note that the current English wording of the baptismal prayer differs from the examples given in the English translation of the Book of Mormon, without compromising its essential elements.155 Moreover, the specific wordings of LDS ordinances in their non-English translations have been updated periodically when better translations were found — with no loss of efficacy.

Going further, Elder Bruce R. McConkie noted that three different ordinances — baptism, the sacrament, and animal sacrifice — were instituted at different times, using different tangible symbols, and in different types of settings, but all in association with one and the same covenant.156 Though these three ordinances vary significantly in their expressions of relevant symbolism, each of them “is performed in similitude of the atoning sacrifice by which salvation comes.”157 What is important in all ordinances, including temple ordinances, is that any adaptations to different times, cultures, and practical circumstances be done under prophetic authority in order to minimize the possibility of changes that alter them in crucial ways.[Page 182]

Adaptations in the Presentation of the Ordinances

With respect to the constrained circumstances under which temple ordinances often have been performed, recall that in the time of the patriarchs and early prophets, they were enacted in open air on the “mountain top”158 or perhaps at times in a tent dedicated to that purpose.159 Long after the exodus, when Israel was settled in the land and dwelt in peace, King David grieved that he lived in a palace of cedar while the ark of God humbly languished, as it had since the wanderings of his people in the wilderness, within the curtains of a portable Tabernacle.160 It was not until the days of Solomon that a permanent and gloriously fitting House of the Lord was finally dedicated161 — only to be destroyed a few centuries later by the Babylonians.

The conditions under which temple work was performed among the early Saints in our day have also varied due to changing circumstances. When the Nauvoo Temple was still under construction, Joseph Smith was prompted to hasten162 the introduction of the temple ordinances “in an improvised and makeshift way”163 to a select few in the attic story of the Red Brick Store. In one account, he is remembered as lamenting: “Brother Brigham, this is not arranged right. But we have done the best we could under the circumstances in which we are placed.”164 After the death of Joseph Smith, the Saints continued their labors to bring the Nauvoo Temple into a form suitable for the administration of the higher ordinances. However, after only brief use in its hastily completed state, the body of the Church was compelled to leave for the West. Shortly thereafter, the Nauvoo Temple was destroyed by fire and wind. Because the Salt Lake Temple would not be finished for forty years, the Saints in the West begain to receive the temple ordinances in a variety of temporary settings, including the top of Ensign Peak, Brigham Young’s office, the Council House, and the Endowment House.165 Finally, decades after their arrival in Salt Lake City, temples began to dot the landscape in Utah. At last, modern temple ordinances could be carried out in surroundings that equalled their majesty.

The most significant adaptation of the presentation of temple ordinances after that time was the cinematic version of the endowment produced for the Swiss Temple. This development allowed the endowment to be presented “in a single ordinance room and in more than one language with far fewer than the usual number of temple workers.”166 In retrospect, this adaptation of the endowment to different languages was no more consequential than the gradual acccommodation of the film to the sensibilities of today’s Church members, who are accustomed to the techniques and high-quality production values of commercial filmmaking. [Page 183]In contrast to the bare recitals and repeated conventions of ancient ritual,167 in which, for example, the creation drama could only be “conveyed by dialogue offstage,”168 Hugh Nibley has described how the lush visuals, the heightened dramatic portrayals by actors, and the powerful emotional impact of a continuous musical score have enhanced the presentation of the endowment for participants:169

Today the various steps of creation are made vivid to us by superb cinematographic and sound recordings, showing the astral, geological, and biological wonders described by the actors and the vast reaches of time that the gods called days before time was measured unto man. Along with that, we are regaled by haunting background music that touches the feelings without intruding on the attention of the audience.

Though recognizing the value of these advances, Nibley worried that overuse of sophisticated theatrical components aimed at enriching the sensory and emotional experience sometimes might distract temple-goers from a focus on the rich meaning conveyed in the words and forms that have functioned traditionally as centerpieces of authentic temple ritual. He observed: “The most impressive temple sessions I have attended have been at Manti where [the live performances of] elderly farm people put on a far more intelligent display than the slick professionals”170 in the films. Note that the live presentation of the endowment continues in both the Manti and Salt Lake Temples.

The advantage of the variety of interpretations experienced in live presentations of the endowment is preserved by the rotation of multiple films in most temples today. For example, in 2014 The Deseret News reported that three different films for LDS temple instruction had been released within the previous year. According to the news article: “The script in each of the films is the same. The films are shown in a rotation to provide variety to temple instruction.”171 The similarities and differences between films help temple-goers distinguish essential instruction from cinematic artistry, thus encouraging them to generalize concrete film details to universal application and minimizing the possibility that incidental particulars may be magnified unintentionally into significant doctrinal imperatives. For instance, without some variety in the different film presentations, a given rendition in a specific film of a few measures of moving music at a strategic story juncture or a powerful and highly nuanced expression of emotion — a tear, a glance, a pause, a gesture, or a smile — might overshadow essential verbal clues pointing to the meaning of the temple narrative.[Page 184]

Earthly Ordinances As Reflections of Heavenly Ordinances

Hugh Nibley has described how the instructional approach of the temple endowment provides needed flexibility while affording remarkable stability:172

The Mormon endowment … is frankly a model, a presentation in figurative terms. As such it is flexible and adjustable; for example, it may be presented in more languages than one and in more than one medium of communication. But since it does not attempt to be a picture of reality but only a model or analog to show us how things work, setting forth a pattern of man’s life on earth with its fundamental whys and wherefores, it does not need to be changed or adapted greatly through the years; it is a remarkably stable model.

Moreover, consistent with the idea that the temple is a model or analog rather than a picture of reality, is the distinction that Elder John A. Widtsoe made between earthly and heavenly ordinances:173

Great eternal truths make up the Gospel plan. All regulations for man’s earthly guidance have their eternal spiritual counterparts. The earthly ordinances of the Gospel are themselves only reflections of heavenly ordinances. For instance, baptism, the gift of the Holy Ghost, and temple work are merely earthly symbols of realities that prevail throughout the universe; but they are symbols of truths that must be recognized if the Great Plan is to be fulfilled. The acceptance of these earthly symbols is part and parcel of correct earth life, but being earthly symbols they are distinctly of the earth and cannot be accepted elsewhere than on earth. In order that absolute fairness may prevail and eternal justice may be satisfied, all men, to attain the fulness of their joy, must accept these earthly ordinances. There is no water baptism in the next estate nor any conferring of the gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of earthly hands. The equivalents of these ordinances prevail no doubt in every estate, but only as they are given on this earth can they be made to aid, in their onward progress, those who have dwelt on earth.[Page 185]

The Restoration of Temple Ordinances

Jesus’ parable of the householder finds application in the process by which modern temple ordinances came forth. As an “expert scribe”174 and a “good householder who makes suitable and varied provision for his household,”175 Joseph Smith restored ancient temple worship by bringing “out of his treasure things new and old”176 — perhaps better translated as “things that are new and yet old.”177 In other words, as one New Testament scholar observed, the “secrets themselves are not really ‘new’; they are ‘things hidden since the foundation of the world,’178 and it is only their revelation which is new.”179

Moreover, the Nauvoo temple ordinances should not be regarded as a new and surprising development so much as the full-fledged blossoming of ideas and priesthood authority that had already budded in Kirtland — or even, arguably, when Joseph Smith experienced his First Vision.180 As Don Bradley perceptively observes:181

The faith [Joseph Smith] preached at the close of his career undeniably differed from the faith he preached at its opening. Yet eminent Yale literary critic Harold Bloom has asserted that Smith’s “religion-making imagination” was of the “unfolding” rather than the evolving type, that his religious system did not transform so much by the incorporation of others’ ideas but by the progressive outworking of his original vision.

To members of the Church who know and love the temple the results of the progressive unfolding of that original vision are palpable. Indeed it might be said that the temple ordinances revealed by the Prophet, like the scripture that came through him, “gave his believing [followers] a sense of what was experientially real, not merely philosophically true.”182 Unlike the allegories of Masonic ritual, which contain beautiful truths while eschewing salvific claims, modern temple ordinances purport a power in the priesthood that imparts sanctity to their simple forms, making earthly symbols holy by connecting them with the living God. In an 1832 revelation, Joseph Smith was told:183

And this greater priesthood administereth the gospel and holdeth the key of the mysteries of the kingdom, even the key of the knowledge of God. Therefore, in the ordinances thereof, the power of godliness is manifest. And without the ordinances thereof, and the authority of the priesthood, the power of godliness is not manifest unto men in the flesh; For [Page 186]without this no man can see the face of God, even the Father, and live.

These verses make it clear that for the Prophet, like John the Apostle, “the specific gift of the power of knowing God is ultimately equated with eternal life itself.”184 However, as Hugh Nibley reminds us, “You comprehend others only to the degree you are like them.”185 This is the whole purpose of the temple: Through the divine influence that flows into all those who learn and live the truths that are made available through participating in temple ordinances and keeping the associated covenants,186 the priesthood becomes a channel of personal revelation187 and a power that enables one to become like God, experiencing “the power of godliness.”

It is my personal witness that the LDS temple ordinances are, as Elder John A. Widtsoe affirmed, “earthly symbols of realities that prevail throughout the universe.”188 They point to heavenly meanings beyond themselves — meanings that can be revealed through our “minding true things by what their mock’ries be.”189 The ordinances perform an essential earthly function, providing “the means both of receiving instruction and demonstrating obedience,”190 helping make us ready, someday, to “behold the face of God,”191 as did Moses. In brief, those who participate in the ordinances of the temple are shown a pattern in ritual of what Moses and others throughout ancient and modern history have experienced in actuality.

Readers, reviewers, and technical editors have kindly made many valuable contributions to this article, but I alone am responsible for the points of view expressed herein. My special appreciation to Manny Alvarez, Don Bradley, Kathleen M. Bradshaw, Brian and Laura Hales, Greg Kearney, Bill and Carolyn Kranz, David J. Larsen, Ben McGuire, Don Norton, Jacob Rennaker, Gregory L. Smith, Joe Steve Swick III, Martin Tanner, Keith Thompson, and Ted Vaggalis. My thanks to Richard L. Bushman for allowing me to quote from an unpublished transcript of his remarks. Thanks to Tim Guymon for his friendship and for lending his editing and typesetting expertise. Chris Miasnik carefully proofread this article as it reached its final form.

This article is dedicated to Robert W. Peterson, my father-in-law, who left this life on January 19, 2015. Among other callings, he served a mission in the Stockholm Sweden temple with his wife, Lori. Like Heber C. Kimball, he was true to his Masonic brethren and to his brethren in the Church.[Page 187]

References

[Page 188]Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Anderson, Gary N., ed. Mormonism and the Temple: Examining an Ancient Religious Tradition (29 October 2012). Academy for Temple Studies Symposium. Utah State University, Logan, UT: BYU Studies, Utah State University Department of Religious Studies, and the Academy for Temple Studies, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZGYrQeZ5xkZfJ5Q7mjZonw. (accessed November 10, 2014).

Anderson, James. 1723. The Constitutions of the Free-Masons (1734). An Online Electronic Edition. Online electronic edition ed. Faculty Publications, University of Nebraska Libraries 25. Philadelphia, PA: Franklin, Benjamin, 1734. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=libraryscience. (accessed March 28, 2015).

Andrus, Hyrum L., and Helen Mae Andrus, eds. 1974. They Knew the Prophet. American Fork, UT: Covenant, 2004.

Attridge, Harold W., and Helmut Koester, eds. Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews. Hermeneia — A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible, ed. Frank Moore Cross, Klaus Baltzer, Paul D. Hanson, S. Dean McBride, Jr. and Roland E. Murphy. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1989.

Bachman, Danel W. “The authorship of the manuscript of Doctrine and Covenants Section 132.” In Eighth Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, 27–44. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1980.

———. “New light on an old hypothesis: The Ohio origins of the revelation on eternal marriage.” Journal of Mormon History 5 (1978): 19–32.

———, Donald W. Parry, Stephen D. Ricks, and John W. Welch. 2014. A Temple Studies Bibliography. In Academy for Temple Studies. http://www.templestudies.org/home/introduction-to-a-temple-studies-bibliography/. (accessed November 10, 2014).

Baker, LeGrand L., and Stephen D. Ricks. Who Shall Ascend into the Hill of the Lord? The Psalms in Israel’s Temple Worship in the Old Testament and in the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2009.

[Page 189]Barker, Margaret. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. King of the Jews: Temple Theology in John’s Gospel. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2014.

———. The Older Testament: The Survival of Themes from the Ancient Royal Cult in Sectarian Judaism and Early Christianity. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 1987.

Barney, Ronald O. 2013. Joseph Smith’s Visions: His Style and his Record. In Proceedings of the 2013 FAIR Conference. http://www.fairlds.org/fair-conferences/2013-fair-conference/2013-joseph-smiths-visions-his-style-and-his-record. (accessed September 15, 2013).

Bednar, David A. “Honorably hold a name and standing.” Ensign 39:5, May 2009, 97–100.

———. Power to Become: Spiritual Patterns for Pressing Forward with a Steadfastness in Christ. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2014.

Belnap, Daniel L., ed. By Our Rites of Worship: Latter-day Saint Views on Ritual in Scripture, History, and Practice. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

Bennett, John C. The History of the Saints; or An Exposé of Joe Smith and Mormonism. Boston, MA: Leland and Whiting, 1842.

Benson, Ezra Taft. 1977. A vision and a hope for the youth of Zion (12 April 1977). In BYU Speeches and Devotionals, Brigham Young University. http://speeches.byu.edu/reader/reader.php?id=6162. (accessed August 7, 2007).

Bérage, M. de. Les Plus Secrets Mystères des Hauts Grades de la Maçonnerie Dévoilés, ou le Vrai Rose-Croix, Traduit de l’Anglois; Suivi du Noachite, Traduit de l’Allemand. Jerusalem, 1766. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=RKpiXLrpI8sC. (accessed June 3, 2015).

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Black, Susan Easton. “James Adams of Springfield, Illinois: The link between Abraham Lincoln and Joseph Smith.” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 1 (Spring: 33–49).

Bloom, Harold. The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

[Page 190]Bogdan, Henrik, and Jan A. M. Snoek, eds. Handbook of Freemasonry. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion 8, ed. Carole M. Cusack and James R. Lewis. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2014.

Bowen, Matthew L. “’And there wrestled a man with him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s adaptations of the onomastic wordplay of Genesis.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 151–60. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/and-there-wrestled-a-man-with-him-genesis-3224-enoss-adaptations-of-the-onomastic-wordplay-of-genesis/. (accessed January 21, 2015).

———. “Founded upon a rock: Doctrinal and temple implications of Peter’s surnaming.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 9 (2014): 1–28. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/founded-upon-a-rock-doctrinal-and-temple-implications-of-peters-surnaming/. (accessed October 29, 2014).

Bradley, Don. “‘The grand fundamental principles of Mormonism’: Joseph Smith’s unfinished reformation.” Sunstone, April 2006, 32-41.

———. Unpublished manuscript in the possession of the author, 19 July 2010, cited with permission.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The ark and the tent: Temple symbolism in the story of Noah.” In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 25–66. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

———. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4–49.

———. “The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text.” BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39–73.

———. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Temple Themes in the Keys and Symbols of the Priesthood. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, in preparation.

———. “The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary.” In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and [Page 191]Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49–65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

———, and Ronan J. Head. “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1–42.

———, and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Brown, Matthew B. Exploring the Connection Between Mormons and Masons. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2009.

———. The Gate of Heaven: Insights on the Doctrines and Symbols of the Temple. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 1999.

———. “The Israelite temple and the early Christians.” Presented at the FAIR Conference, August, 2008. http://www.fairlds.org/fair-conferences/2008-fair-conference/2008-the-israelite-temple-and-the-early-christians. (accessed 3 May 2012).

———, and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. The Throne of God. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, in preparation.

———, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson, eds. Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011. Temple on Mount Zion Series 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

———, and Paul Thomas Smith. Symbols in Stone: Symbolism on the Early Temples of the Restoration. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 1997.

Brown, Samuel Morris. In Heaven As It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2012.

———. “William Phelps’s Paracletes, an early witness to Joseph Smith’s divine anthropology.” International Journal of Mormon Studies 2 (Spring 2009): 62-82.

Brown, William P. The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, A Cultural Biography of Mormonism’s Founder. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

[Page 192]———. “Response.” In 2013 BYU Church History Symposium: Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith’s Study of the Ancient World. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT, 2013. http://religion.byu.edu/event/2013-byu-church-history-symposium. (accessed October 27, 2013).

Calabro, David. “The divine handclasp in the Hebrew Bible and in Near Eastern Iconography.” In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 83–97. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

———. “Joseph Smith and the Architecture of Genesis.” In Online Proceedings of the Conference “The Temple on Mount Zion,” Provo, Utah, September 22, 2014. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/events/2014-temple-on-mount-zion-conference/program-schedule/. (accessed October 27, 2014). To be published in a forthcoming volume edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry and published by Orem and Salt Lake City, Utah: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books.

———. “‘Stretch forth thy hand and prophesy’: The symbolic use of hand gestures in the Book of Mormon and other Latter-day Saint scripture.” Presented at the Laura F. Willes Center Book of Mormon Conference, Provo, UT, September, 2010.

———. “Understanding ritual hand gestures of the ancient world.” In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion Series 1, 143–57. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

———. “’When you spread your palms, I will hide my eyes’: The symbolism of body gestures in Isaiah.” Studia Antiqua: A Student Journal for the Study of the Ancient World 9, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 16–32. http://studiaantiqua.byu.edu/PDF/Studia 9-1.pdf. (accessed March 12, 2012).

Callender, Dexter E. Adam in Myth and History: Ancient Israelite Perspectives on the Primal Human. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2000.

Coleson, Joseph E. “Israel’s life cycle from birth to resurrection.” In Israel’s Apostasy and Restoration: Essays in Honor of Roland K. [Page 193]Harrison, edited by Avraham Gileadi, 237–50. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1988.

Compton, Todd M. “The handclasp and embrace as tokens of recognition.” In By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 611–42. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990.

———. “The whole token: Mystery symbolism in classical recognition drama” (Typescript of article in the possession of the author). Epoché: UCLA Journal for the History of Religions 13 (1985): 1–81.

Cowan, Richard O. “The design, construction, and role of the Salt Lake Temple.” In Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, edited by Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford. Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History. Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011.