[Page 355]Abstract: Jonathan Neville, an advocate of the “Heartland” geography setting for the Book of Mormon, claims to have identified a novel chiastic structure that begins in Alma 22:27. Neville argues that this chiasmus allows the reconstruction of a geography that stretches south to the Gulf of Mexico in the continental United States. One expert, Donald W. Parry, doubts the existence of a fine-tuned chiasmus in this verse. An analysis which assumes the presence of the chiasmus demonstrates that multiple internal difficulties result from such a reading. Neville’s reading requires two different “sea west” bodies of water: one “sea west” placed at the extreme north of the map and a second sea to the west of Lamanite lands, but neither is to the west of the Nephites’ land of Zarahemla. Neville’s own ideas also fail to meet the standards he demands of those who differ with him. These problems, when combined with other Book of Mormon textual evidence, make the geography based upon Neville’s reading of the putative chiasmus unviable.

Jonathan Neville has recently emerged as an advocate of the “Heartland” geographical setting for the Book of Mormon.1 One essential aspect of Neville’s theorizing is a chiastic reading of Alma 22:27–34, which is a key geographical passage.2 This would be a valuable addition to parallelistic textual patterns within the Book of Mormon (301–320).3

Neville notes that this chiasmus was not discussed in Donald Parry’s Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon (286).4 He reports:

[Page 356]There are some parallel structures identified in the early parts of Alma 22, but none after verse 17. I met with Dr. Parry on 14 January 2015 to discuss my findings. He agreed that verses 27–34 have chiastic elements that he had not seen before. Pending his further review, in this article I [Neville] present my own ideas (286).

I wrote to Parry to inquire about his conclusions. He replied:

In my work Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon, I specifically did not format Alma 22:27 as a chiasmus because the verse lacks the proper corresponding elements and structure to be a proper chiasmus. Although it is evident that bordering, east, west, and land of Zarahemla correspond with land of Zarahemla, borders, east and west (within the same passage), other elements of the passage break down the idea of a fine-tuned chiasmus.5

I here assume—for the sake of argument—that Neville is correct and that this passage is chiastic, though Parry’s expertise weighs heavily against this assumption. It is still instructive to see where this assumption leads us. I believe it functions as a type of reductio ad absurdum: assuming the truth of a proposition yields an unworkable answer, demonstrating that the claim is likely false, at least as Neville has used it.

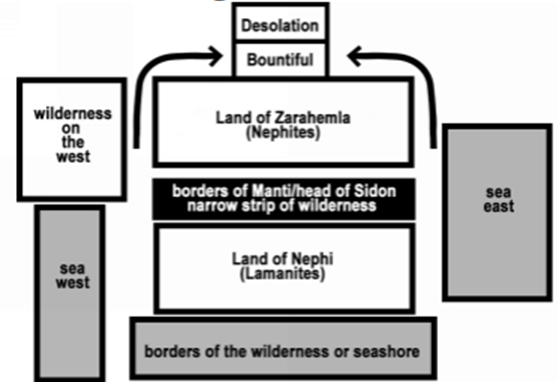

Happily, Neville takes the vital step of using his reading of the scripture to begin constructing an internal geography: a theoretical map that incorporates how he reads the text into a visual diagram. He carries this diagram through several iterations; a representative one appears in Figure 1.6 This figure, however, lacks an important element of Neville’s geography: it does not include a sea west near the land of Bountiful, at the “narrow neck of land.” Neville is, however, very definite that there is not a continuous “sea west” from Lamanite lands to Nephite lands in the north. (The omission of the northern “sea west” from the schematic diagram is potentially misleading; it omits one of the most contentious novelties of Neville’s model.)

[Page 357]Even if we grant that the identification of this section of Alma 22 as chiastic is potentially important, it does not seem to make a huge difference in how we read this section for geographic purposes. “In the case of Alma 22:27–34,” Neville says, “the parallel structures provide an entirely new abstract geography … that suggests a predominantly east/west orientation of the Nephite territory” (319–320, emphasis added). Yet, in most respects, Neville’s internal geography does not differ substantially from views of those who have read these verses without the benefit of the chiastic insight. For example, Sorenson’s model of the same features (reproduced in Figure 2) looks substantially the same (though the seas are not labeled in Sorenson’s diagram, they are clearly present).7 The key difference is the “sea west” — Sorenson’s is westward, while Neville has two features which share the name. How does Neville arrive at this layout? He first draws on verse 27, and Table 1 reproduces his chiastic interpretation, which will make his reading clearer.

[Page 358]

Table 1: Neville’s chiastic reading of Alma 22:27 (from Neville, 301). Bold, underlines, and punctuation in original.

A amongst all his people who were in all his land who were in all the regions round aboutB which was bordering even to the sea on the east and on the west andC which was divided from the land of Zarahemla by a narrow strip of wilderness,D(a) which ran from the sea eastD(b) even to the sea westD1(a) and round about on the borders of theseashoreD1(b) and the borders of the wildernessC1 which was on the north by the land of ZarahemlaB1 through the borders of Manti by the head of the river Sidon running from the east towards the west A1 –and thus were the Lamanites and the Nephites divided.

[Page 359]Neville argues:

Lines B and B1 refer to the east/west orientation of the Lamanite land. B explains that the land was bordering even to — in other words, extended as far as — the sea on the east and on the west. The omission of the term sea before on the west leaves the phrase somewhat ambiguous. The text could have said “the sea on the east and the sea on the west.” Alternatively, it could have said “the seas on the east and on the west.” The ambiguity can be resolved by inferring either that there was [not? – sic] a sea on the west, or that if there was a sea, the border did not coincide with it; i.e., the border may have extended beyond or fallen short of any sea west. Or maybe it was just undefined — somewhere out west (302).

If a paralellistic pattern is intended in these lines, as Neville believes, it is indeed strange that the line does not read “even to the sea on the east and the sea on the west.” There is, however, a more serious potential problem for Neville’s reading. In lines C, Da, and Db we are told explicitly that there is “a narrow strip of wilderness, which ran from the sea east even to the sea west.” Thus the wilderness stretches from sea to sea, which would seem to rule out both the possibility that there is no sea west, or that the borders of the narrow strip do not encounter a more distant sea west. Given that this clarification immediately follows the ambiguous line to which Neville has called our attention (and upon which interpretation much of his analysis rests), it seems that the ambiguity is an artifact of Neville’s decision to break the text into small, chiasmus-fragment units for analysis. A reader of the text without this interpretive apparatus would simply read, “his people who were in all his land … which was bordering even to the sea, on the east and on the west, and which was divided from the land of Zarahemla by a narrow strip of wilderness, which ran from the sea east even to the sea west” (Alma 22:27, emphasis added). The second phrase clarifies the intent of the first, and in this case the modern punctuation which has the sea modified by both “on the east and on the west” is almost certainly correct.

Surprisingly, Neville seems to concede the force of this analysis when he later writes that “an obvious question arises about the sea west, which is mentioned in D(b) but not in B. This supports the interpretation that the sea was omitted in B because it was implied” (304). Indeed it does. But, if so, why all the torturous effort to cast doubt on the existence of a “sea west”?

[Page 360]Neville writes:

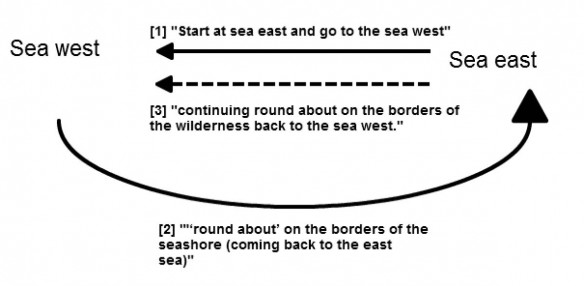

D describes the east/west boundary [of the Lamanite king’s land], while D1 describes the north/south boundary. You start at the sea east and go to the sea west, then “round about” on the borders of the seashore (coming back to the east sea) and continuing round about on the borders of the wilderness back to the sea west.

We understand the “borders of the seashore” are on the south because we’re also told that the north part of the king’s land was the wilderness bordering on the land of Zarahemla. (303–304)

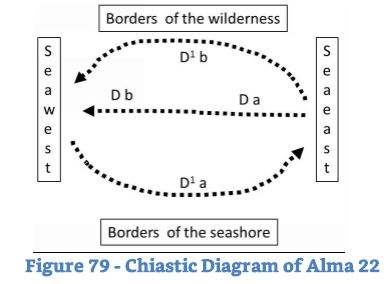

This reader is not certain he understands. To aid in visualization, I created a diagram in Figure 3 that illustrates Neville’s reading.

Figure 3: Graphic representation of Neville’s chiastic reading of Alma 22:27. See Neville’s similar schema in his Figure 79 (Neville, 303, see Figure 4).

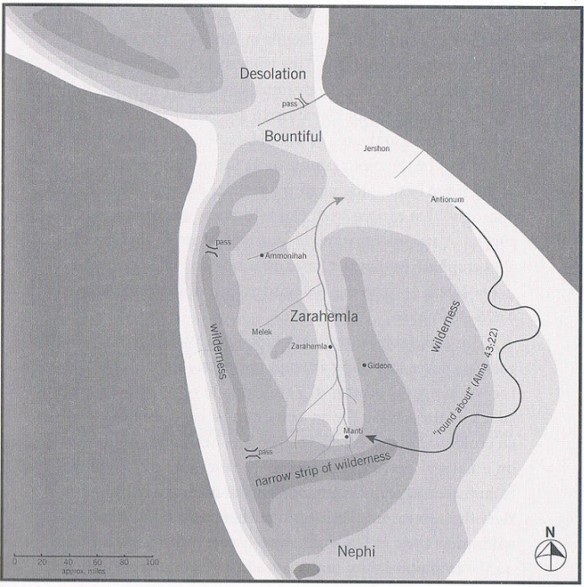

Neville’s Figure 79 (303) [reproduced in Figure 4] sees D1(a) (“round about on the borders of the seashore”) as describing a deep southern route, while D1(b) (“and the borders of the wilderness”) details the far northern reaches of the Lamanite king’s realm.[Page 361]

This is a tricky, close argument to follow, so I make explicit what I take to be his five contentions:

- The Da-Db-D1a- D1b center of the chiasm is intended to describe the north/south and east/west boundaries of the Lamanite king’s land.

- D1a and D1b describe the extreme north/south Lamanite borders.

- Da and Db describe seas to the east and west.

- There are “borders of the seashore” at the far south of the Lamanite lands.

- The west boundary of Nephite territory is partly sea and partly landmass.

Let us examine each point in turn. The first two are the most involved; once they have been examined, the others fall into place easily.

1. Chiastic Center Describes Borders of the Lamanite King’s Land, North/South and East/West

We must remember that the claim that this is properly read as a chiasmus, and that the putative center is intended to describe the four [Page 362]boundaries of the entire Lamanite lands, is a hypothesis. It is not stated in the text.

If this is a chiasmus, then, as Neville notes, the center ought to be the most important “turning point” (303). John W. Welch reminds us, “The crux of a chiasm is generally its central turning point. Without a well-defined centerpiece or distinct crossing effect, there is little reason for seeing chiasmus.”9 But, as Neville has analyzed Alma 22:27 (see Table 2), the lines do not seem especially chiastic by these criteria.

We might expect a chiastic structure to pair sea east with sea west, and borders of the seashore with borders of the wilderness. In a chiasmus, this would normally be laid out to achieve an A-B-B-A pattern (e.g., sea-borders-borders-sea). As seen in Table 2, we have A-A-B-B (sea-sea-borders-borders). So perhaps we are mistaken in seeing this as chiastic or at least chiastic as Neville has diagrammed it. For Neville to be correct, the putative chiastic “reflection” must be understood differently: the seas are not the parallel elements but are instead each paired with another element to which they are related. This claim risks being circular, however, since there is no a priori reason to see the elements paired as Neville wishes, save his presumption that we are dealing with a chiasmus.

Table 2: Purported Chiastic Center Detail of Alma 22:27 (Neville, 301), Label of “Turning point” Added for Clarity

D (a) which ran from the sea east(b) even to the sea west[Turning point]D1 (a) and round about on the borders of the seashore

(b) and the borders of the wilderness

As Nils Lund noted of chiasmus, “The centre is always the turning point. At the centre there is often a change in the trend of thought and an antithetic idea is introduced.”10 It is not at all clear, however, that here we have much of a turning point at all. There is certainly no change in the thought, or transformation of the thrust of the passage. These deficits call Neville’s reconstruction into further doubt.

2. D1a and D1b Describe the North/South Borders

If Table 2 is a chiastic center, then sea east is linked to borders of the seashore (Da–D1a), and sea west with borders of the wilderness (Db–D1b). [Page 363]Neville reads this as a complete circle of boundaries circumscribing all the Lamanite land, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (his Figure 79).

But why? In Neville’s reading, Mormon has described both the northern boundary and the narrow strip of wilderness. But Neville claims that the intent of the chiasmus is to describe the entire Lamanite territory. As diagramed, however, he has not walked us “around” the territory but has instead bisected it and then walked around the Lamanite borders north and south of the narrow strip of wilderness (see Figure 4, his Figure 79).

Of what relevance is the narrow strip of wilderness to the entire Lamanite territory if it is not one of the boundaries? The narrow strip has typically — and, to my mind, properly — been seen as the de facto border between the Nephites and Lamanites.11 Why, then, does Mormon — a Nephite general — concede Lamanite sovereignty over an area north of the narrow strip in Neville’s model? “The sequence of the northern [Lamanite] border,” writes Neville, “from east to west, goes like this: Zarahemla, head of Sidon, Manti” (303). This apparently places the northwestern edge of Lamanite territory right on the border of Zarahemla, which is well north of the narrow strip of wilderness.

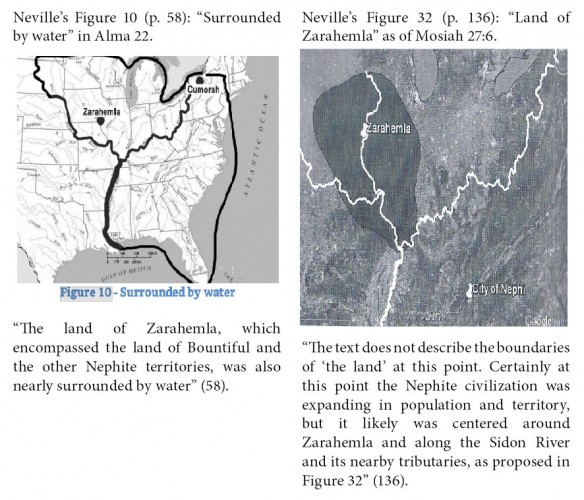

It is not clear if he is here referring to the city of Zarahemla or the land of Zarahemla. To add to the confusion, Neville defines the “land of Zarahemla” as all Nephite-controlled land including “the land of Bountiful and other Nephite territories” but without extending beyond the narrow strip [58, Figure 10, see Table 3]. Elsewhere, he portrays it as extending well south of the “narrow strip of wilderness” [136, Figure 32, see Table 3].

[Page 364]

Table 3: Neville’s Variable Configuration of “the land of Zarahemla.”

He elsewhere says that “in my analysis, I assume designation of a land means either the area administered by the government located in the city of the same name, or the area in general proximity of [sic] the city of the same name” (144). This terminological variation and imprecision allows him considerable interpretive flexibility regarding the meaning of “land of Zarahemla” in any given verse, which in my judgment renders the text far too malleable in his hands. I think the larger area in his Figure 10 is, in any case, far too large to be administered by the city government in Zarahemla, and this may be true of Figure 32 as well.

Despite these confusing aspects, the Book of Mormon explicitly rules out the configuration that Neville’s narrow strip boundary of Zarahemla — head of Sidon — Manti requires, as we will now see.

Captain Moroni’s son, Moronihah, would suffer a somewhat embarrassing defeat when a later Lamanite army smashed through the Nephites’ southern borders to capture the relatively undefended capital city of Zarahemla. Mormon excuses Moronihah’s disposition of his troops, noting that although “they had not kept sufficient guards [Page 365]in the land of Zarahemla,” this was because “they had supposed that the Lamanites durst not come into the heart of their lands to attack that great city Zarahemla” (Helaman 1:18, emphasis added in all cases). “This march of Coriantumr through the center of the land gave Moronihah great advantage,” (1:25) Mormon editorializes, “For behold, Moronihah had supposed that the Lamanites durst not come into the center of the land, but that they would attack the cities round about in the borders as they had hitherto done” (1:26). The Lamanites “had come into the center of the land, and had taken the capital city which was the city of Zarahemla” (27), and this initial tactical success had only “plunged the Lamanites into the midst of the Nephites, insomuch that they were in the power of the Nephites” (1:32) since “the Lamanites could not retreat either way, neither on the north, nor on the south, nor on the east, nor on the west, for they were surrounded on every hand by the Nephites” (1:31). This is simply not a description of a city acting as a border with the hostile Lamanite polity, as Neville’s model claims.

It would also be difficult to argue that Mormon is engaging in a type of political rhetoric in which Lamanite control of land north of the narrow strip of wilderness near Zarahemla is ignored or contested in official propaganda, even though the Lamanite border “really” extended as far as Neville’s model requires. No, Nephite generals count on Zarahemla’s relative safety and distance from any Lamanite threat as a key tactical reality — Moronihah was surprised by Coriantumr’s assault precisely because it was strategically suicidal to plunge so deeply into enemy territory while leaving Nephite armies and territories in the Lamanite rear. No one as pragmatic as Mormon, Moroni, and Moronihah would have let propaganda dictate how they understood such a key military issue.

Moronihah’s father (Moroni) likewise indicates that Zarahemla is nowhere near the Lamanite threat, either from the south-western or -eastern theatres. He blasts the governing class at Zarahemla, accusing them of “sit[ting] upon your thrones in a state of thoughtless stupor” (Alma 60:7), perhaps “because ye are in the heart of our country and ye are surrounded by security” (60:19). It is clear, then, that the Nephites could be sorely pressed in and around the southern border while Zarahemla could still repose complacently in considerable safety. In fact, Helaman’s armies in the south and west faced starvation conditions while holding the Nephite line, yet remained ignorant of conditions in Zarahemla. They neither knew why supplies and reinforcements had not reached them, nor what the political situation was at home (58:34–36). This [Page 366]cannot have been a matter of somehow being surrounded by Lamanites and thus besieged, since letters and prisoners could be sent to Zarahemla (57:15–17, 30–33), and relief forces and food supplies from the capital were eventually able to reach the southern front without a battle (61:16; 62:12).

Furthermore, Helaman’s small band “having traveled much in the wilderness towards the land of Zarahemla” (58:23) from Manti eventually frightened the Lamanite army by persistent “marching towards the land of Zarahemla” (58:24). Again, we see considerable travel effort between the frontiers before even approaching “the land” (much less the city) of Zarahemla — neither of Neville’s maps allows this construction. All of this demonstrates that Mormon’s focus on the narrow strip of wilderness reflects a key Nephite tactical reality: the strip is the key northern Lamanite border. If Neville is arguing that Lamanite territory lies to the north of the narrow strip near Zarahemla, this is not borne out by the text. If he agrees that the northern border is contiguous with the narrow strip of wilderness, then his chiasmus structure makes even less sense, as Moroni gives us two trips over the east to west northern border (see my Figure 3 above).

I think the real goal of Neville’s reading is to allow him to assume the existence of a seashore around the southern end of Lamanite territory — a feature otherwise unattested in the Book of Mormon, and far from the areas of Nephite interest or interaction. Such a reading does not really make much of the chiastic parallelism that Neville believes he has identified. We note that by breaking up the lines for the chiastic analysis, he has also separated the which in Da from its antecedent: the narrow strip of wilderness. Once again, the focus on the narrow strip is incongruent if the Lamanite border is far to the north, near Zarahemla, but completely understandable if we see the narrow strip for what it clearly is: the key Nephite frontier against the Lamanites.

I suspect that Neville’s error in Alma 22 hinges on ignoring that there is another wilderness on the east, as his own diagram shows. It is from this eastern wilderness that Captain Moroni later drives the Lamanites southward, in order to fortify his defensive east/west line along or near the narrow strip. (I return to this point a few paragraphs below.) Let’s look at the phrase again without the chiastic markings that create this artificial separation (I have, following Neville’s practice [13, 286], omitted the modern punctuation):

[the Lamanite land] was divided from the land of Zarahemla by a narrow strip of wilderness which ran from the sea east [Page 367]even to the sea west and round about on the borders of the seashore and the borders of the [east?] wilderness which was on the north [of Lamanite lands] by the land of Zarahemla through the borders of Manti by the head of the river Sidon.

The thing which runs “round about on the borders of the seashore” seems to me to refer not to the Lamanite king’s complete boundaries (much less to the extreme south of his realm), as Neville claims, but exclusively to the same narrow strip of wilderness, north of the Lamanites. That we are still talking about the narrow strip is evident, since this section concludes, “through the borders of Manti by the head of the river Sidon,” and Manti and the Sidon’s head are in the southern reaches of Nephite territory, just north of the narrow strip of wilderness (as even Neville concedes, 303).

My proposed interpretation is supported by Mormon’s later description of a tactic used by Captain Moroni to increase Nephite security:

And it came to pass that Moroni caused that his armies should go forth into the east wilderness; yea, and they went forth and drove all the Lamanites who were in the east wilderness into their own lands, which were south of the land of Zarahemla.

And the land of Nephi did run in a straight course from the east sea to the west.

And it came to pass that when Moroni had driven all the Lamanites out of the east wilderness, which was north of the lands of their own [i.e., Lamanite] possessions, he caused that the [Nephite] inhabitants who were in the land of Zarahemla and in the land round about should go forth into the east wilderness, even to the borders by the seashore, and possess the land. (Alma 50:7–9, emphasis added)

This “east wilderness” seems a strong candidate for the “borders of the [east] wilderness which was on the north [of Lamanite lands] by the land Zarahemla” (Neville’s D1 and C1 of Alma 22:27), with which the narrow strip of wilderness merges on the east. Verse eight might seem to reinforce Neville’s reading of B — we again have an east sea but only a reference to west without a sea. But, before we become too enamoured of this possibility, the next two verses call it into question:

And [Moroni] also placed armies on the [Nephite] south [i.e., the Lamanite north], in the borders of their possessions, and [Page 368]caused them to erect fortifications that they might secure their armies and their people from the hands of their enemies.

And thus he cut off all the strongholds of the Lamanites in the east wilderness, yea, and also on the west, fortifying the line between the Nephites and the Lamanites, between the land of Zarahemla and the land of Nephi, from the west sea, running by the head of the river Sidon (Alma 50:10–11, emphasis added).

Mormon thus gives us a picture of a “straight course from the east sea to the west,” which separates Lamanite and Nephite territory, with an explicit mention of fortifications from the west sea. Helaman would later march “as if we were going to the city beyond, in the borders by the seashore” (Alma 56:31; compare 53:22), which likewise suggests that a Nephite city near the west seashore anchored the Nephite line of defense.

This west sea must, therefore, be placed at the northern end of Lamanite territory, and be sufficiently large that the Lamanites cannot simply detour around it. We also know that it extends as far north as the narrow neck of land, since Hagoth launches ships “into the west sea, by the narrow neck which led into the land northward” (Alma 63:5).12 A later reference makes it again clear that the west sea is near the Nephite borders:

And now it came to pass that the armies of the Lamanites, on the west sea, south, while in the absence of Moroni on account of some intrigue amongst the Nephites, which caused dissensions amongst them, had gained some ground over the Nephites, yea, insomuch that they had obtained possession of a number of their cities in that part of the land (Alma 53:8).

Alma 53:8 is a description of Nephite reverses, thus in the south of the Nephite lands (which is north of Lamanite lands). Mormon presumably clarifies with south because the west sea stretches from at least the southern Nephite borders to the narrow neck in the north. It is important for the reader to realize that the problem occurs on the southern border, not somewhere along the Nephite western flank. Helaman will later lead his two thousand men “to the support of the people in the borders of the land on the south by the west sea” (Alma 53:22). So once again, the existence of a sea west bounding Nephite lands is both explicit, and placed near the northern Lamanite borders, at the southern extent of Nephite territory.

[Page 369]Later Nephites will likewise explicitly spread from a sea west to sea east:

[T]he people of Nephi began to prosper again in the land, and began to build up their waste places, and began to multiply and spread, even until they did cover the whole face of the land, both on the northward and on the southward, from the sea west to the sea east. (Helaman 11:20, emphasis added)

This moves the sea west’s boundary north of the narrow neck, which serves as the boundary between the land northward and southward. We thus have the sea west from at least the narrow strip of land, to the land northward (at least north of “Bountiful” in Neville’s map, Figure 1).13

All of this makes it increasingly difficult to accept Neville’s far southern “loop around” hypothesis at a chiastic center of Alma 22:27 as the proper reading. Far from describing a loop southward (through an area that never comes into the story, and which is of no importance to Nephite warfare or security) or the entire Lamanite territory, Alma 22:27 seems to detail the dimensions and rough boundaries of the vital narrow strip of wilderness that Nephite generals had to defend. Parry is, I suspect, right: “other elements of the passage break down the idea of a fine-tuned chiasmus.”14

3. Da and Db Describe Seas to the East and West

This contention seems to me true of the line along the narrow strip of wilderness, at least, and if there are seas there, they would constitute the borders of Lamanite land. This seems the only incontestable part of Neville’s reading.

4. There are “borders of the seashore” at the South of the Lamanite Lands

To repeat, this seems rather ad hoc. There is clearly a sea west near the narrow strip of wilderness (stretching northward to beyond the narrow neck, unless we accept Neville’s claim that there are two such “west seas” — see the discussion below), and yet Neville insists upon reading references to the borders of the seashore as implying a sea to the south instead. His rationale is examined in the next point.[Page 370]

5. The West Boundary of Nephite Territory is Partly Sea and Partly Landmass

As illustrated in point 2 above, the west sea must stretch at least from the narrow strip of wilderness in the Nephite south to the narrow neck in the north, and likely beyond that. Neville, however, disputes this in his reading of Alma 22:28. He again produces a parallelistic reading of the verse (though not a chiastic one), which I reproduce in Table 4 for clarity.

Table 4: Parallelistic Analysis of Alma 22:28 (Neville, 305)

Now, the more idle part of the Lamanites lived in the wilderness, and dwelt in tents

A and they were spread through the wilderness on the west in the land of Nephi

C [yea, and also on the west of the land of Zarahemla] B in the borders by the seashore A1 and on the west in the land of Nephi, in the place of their fathers’ first inheritance

B1 and thus bordering along by the seashore.

This is a much less complex example of parallelism than the previous putatively chiastic one. The insertion of C might lead us to question whether the parallel analysis is correct. Neville treats C “as a sort of parenthetical to A,” that “tells us there is land west of Zarahemla that is not part of the land of Nephi — sort of a no-man’s land, or an unclaimed wilderness where idle Lamanites live in tents” (305). He uses the absence of a counterpart to C in his parallel structure to argue:

the idle Lamanites live on the west in the land of Nephi (within Lamanite territory) and along the borders by the seashore, but setting off C this way suggests that those living on the west of the land of Zarahemla do not live by the borders of the seashore. In other words, those idle Lamanites living in the wilderness west of Zarahemla do not live by a seashore. The “sea west” does not extend north or west far enough to form a western border near Zarahemla … . Verse 28 seems to clarify that all of the west does not border on a sea; only those areas that are in the land of Nephi border on the sea (306, emphasis in original).

Neville thus posits a sea to the west of Lamanite territory, but declines to do so for Nephite territory. But as we have seen already, there are significant indications that a sea west stretches from the narrow strip of wilderness to beyond the narrow neck of land in the north — the Nephites even have an unnamed western city down by the western [Page 371]seashore. There is nothing in this text that would lead us to conclude that the western Lamanites were not “in the borders by the seashore” — only Neville’s parallelistic construction might suggest that this is so. And he cannot even accommodate the key phrase into the parallelistic interpretation; he must make the line which disproves his model a supposed “parenthetical” insertion. It is far simpler, does less violence to the text, and makes fewer assumptions if we simply take the text at its word that there were Lamanites in “the wilderness on the west, in the land of Nephi; yea, and also on the west of the land of Zarahemla, in the borders by the seashore” (Alma 22:28) — west of Zarahemla, there is a seashore with Lamanites. Yet these Lamanites are not a huge tactical concern for Moroni after he fortifies the east/west defensive line, with an anchoring city at its extreme edge’s western seashore. Neville’s model makes it difficult to see why this would be so.

Tactics

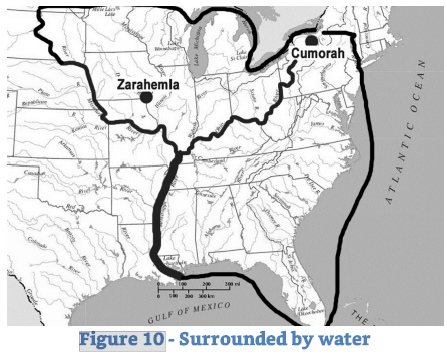

Besides making Moroni’s unconcern for the western Lamanites difficult to understand, an absence of a sea on the west of Nephite territory makes a hash of Lamanite tactical choices during the wars. Neville decides that “the narrow strip of wilderness consists of the Ohio and Missouri Rivers” (53). His figure 9 (reproduced in Figure 5) provides a graphic representation of this, with the lower Mississippi (his southern “sea west”) in a heavier line.

Figure 5: Neville’s Figure 9 (53) — Narrow Strip of Wilderness (Thin Line, the Ohio and Missouri Rivers) and Southern “sea west” (Thick Line, Lower Mississippi River).

[Page 372]Here again, the model encounters major problems. We are told explicitly that Moroni’s defensive line stretches “from the west sea” (Alma 50:11) toward the eastern wilderness from which Moroni has driven the Lamanites and introduced Nephite settlers (Alma 50:9). Neville’s narrow strip, however, continues far to the west beyond his southern “sea west.” One can understand why he does so; if the “narrow strip of wilderness” does not extend as he has diagrammed it, what is to stop the Lamanites from simply crossing to the west bank of the Mississippi deep in their own territory and bypassing the Nephite defensive line anchored at the “sea west”? This would allow them to hit Zarahemla on the west bank of the upper Mississippi/Sidon with ease. But the fact that Neville must thus contradict the text is good evidence that his model isn’t working. Why, with their vastly superior manpower, do the Lamanites never attempt an “end run” to the west around Moroni’s fortified line of defense that stretches along the narrow strip of wilderness? Why does Moroni show no concern at all about fortifying against the vast stretch of territory to the west, which Neville’s model requires? Why is Moroni unconcerned about the Lamanites that inhabit that area, and why does an attack on Zarahemla never come from that direction? As we have already seen, the capital was regarded as very safe, even when the southern Nephite frontier was under assault. Outnumbered as they are, Moroni’s men would not be able to maintain the defensive line with sufficient manpower to repel a determined Lamanite effort to flank them if the geography offered by Neville was even approximately accurate.

Summary

Far from disproving the basic “hourglass” model bounded by seas of Sorenson and others, our analysis of Neville’s reading has essentially reconfirmed it:

a) We agree that there is a sea on the west of the Lamanite polity.

b) A west sea is a likely textual requirement from the northern Lamanite borders to the northern Nephite lands (unless we introduce, as Neville does, a novel “second sea west”; see next section).

c) Furthermore, this west sea acts as an anchor point for Captain Moroni’s fortified east/west line.

[Page 373]These facts argue strongly that there is a single west sea that stretches from southern Lamanite land, north past the Nephites’ territory, to the narrow neck and likely beyond.

Two “West Seas”?

To counter the force of an analysis such as I have just provided, Neville insists that there are, in fact, two bodies of water properly denominated a “sea west.” He declares that his “next step was to find a mighty river that would fit both the chiastic map and the real-world geography” (34). It is not at all clear to me, however, that Alma 22 — or any other part of the Book of Mormon text — demands or even permits two west seas. This requirement seems, instead, to be dictated by Neville’s determination to shoehorn his model into part of North America. In fact, combining the chiastic and real-world map is premature. Neville first ought to prepare and justify a theoretical, internal map without any reference to an external location.

Neville decides, at any rate, that the “sea east” is the Atlantic Ocean (36), the “lower Mississippi” serves as the “sea west” near the narrow strip of wilderness (36), whereas the “west sea” (note the inversion of the terms) near the narrow neck of land near the Nephite land northward is Lake Michigan (37): Mormon “referred to the sea west when he was describing the narrow strip of wilderness that separated the lands of the Nephites from the lands of the Lamanites, and he referred to the west sea when he was describing the land Bountiful, a subset of the larger lands of the Nephites” (36).

I think the difference in terminology is trivial and of no consequence. In fact, only a paragraph later, Neville cites Alma 53, verses 8 and 22. We have just examined these verses in the previous section, in which Helaman and his stripling warriors are said to be “on the west sea south” and “on the south by the west sea.” Thus, in these verses we have Mormon using the term “west sea,” which Neville claims refers to the lower Mississippi in Alma 53, and to northern Lake Michigan in the Alma 22 chiasmus. Thus, to appeal to sea west versus west sea as a meaningful distinction in Alma 22 seems ungrounded and inconsistent. It is also curious that seas denominated as “west” are also both eastward of Zarahemla, which in Neville’s map is west of both the Mississippi and Lake Michigan.

Neville appeals to Hebrew usage (33–34), since the Hebrew word yam, normally rendered sea, is occasionally used to refer to the river Nile (e.g., Isaiah 19:5, Nahum 3:8). While technically possible, this approach smacks of desperation. Why would Mormon — or Joseph Smith as the [Page 374]translator — use “sea” instead of “river”? Why would the Mississippi be denominated a “sea,” the same term applied to Lake Michigan and the Atlantic Ocean? Why would the Nephites’ “river Sidon” (which also corresponds to the upper Mississippi river in Neville’s schema; see 284) be rendered as “river,” while the lower Mississippi is labeled a sea? The Isaiah and Nahum passages are poetic, not attempts to lay out geography for the reader as Mormon is explicitly doing in Alma 22.

Neville answers none of these questions, and betrays no awareness that they ought to be answered. One again has the impression that the text is constantly being measured and contorted for the procrustean bed of Neville’s North American setting.

A Double Standard Applied to Other Authors

This impression is furthered by the way Neville treats those he regards as his ideological opponents. Of Sorenson’s Mesoamerican model, Neville writes:

Now, you might wonder why the sea east is north and the sea west is south of the supposedly “narrow” neck of land that is 125 miles wide. The answer is that Joseph Smith didn’t understand Mayan mythology so he didn’t know how to translate the book correctly. Well, that’s not fair. When he translated 1 Nephi, Joseph translated directions accurately because when Nephi lived in the Middle-East, he used the same cardinal directions we do today. But when he came to the New World, Nephi and his successors immediately rejected the Hebrew customs and embraced Mayan mythology and worldview.15

We will ignore the elements of caricature here and focus on Neville’s key contention: he insists that it is unreasonable for the Book of Mormon’s directional scheme to differ from “the same cardinal directions we use today.” Elsewhere, Neville touts the fact that his model “accepts [the] entire [Book of Mormon] text literally,” including “cardinal directions” and “four seas.”16 Safely unmentioned, however, is the fact that Neville’s “literal” reading of the seas requires the term “sea” to describe many different features: a freshwater lake, a river, and an ocean, while another part of the same river is termed a “river,” and both seas are labeled west though located east of the Nephite capital and heartland. Accepting a text “literally” is, it would seem, in the eye of the beholder.

Neville elsewhere expands on this claim at length, arguing that

[Page 375][Brant] Gardner’s response to both Wunderli and Matheny reflects his skepticism about the accuracy of Joseph’s translation: “Although the English text of the Book of Mormon subconsciously encourages us to read our own cultural perceptions into directional terms, the text’s internal consistency tells us that the directional system works. If we allow the hypothesis that the text is a translation of an ancient document, then the modern assumption of directions is the problem, not the presentation in the Book of Mormon.”

“Our own cultural perceptions” is a euphemism for “ordinary meaning of the English language.”17

The key point, for our purposes, is that Neville insists — when it comes to directions — that Joseph Smith’s translation must match modern western ideas about cardinality. To do otherwise is to threaten Joseph’s status as a translator:

Basically, the Mesoamerican proponents insist that Joseph Smith mistranslated the Book of Mormon. Here’s how Gardner puts it: “We have evidence that Joseph dictated ‘north.’ What we do not have evidence of is what the text on the plates said.” So Joseph Smith’s translation is not evidence of what the plates said!

It is difficult to conceive of an argument that undermines the Book of Mormon more than this one. Not even Wunderli goes that far. If Joseph’s translation of “north” is not evidence of what the plates said, is anything he translated evidence of what the plates said?18

No Mesoamerican theorist, to my knowledge, has ever argued that Joseph “mistranslated” the Book of Mormon text or that he used “the wrong terms.” They have, however, recognized that translation is not necessarily a straightforward process. Neville insists that when Sorenson, Gardner, et al. speak of “our own cultural perceptions,” that this “is a euphemism for ‘ordinary meaning of the English language’,” which is a spectacularly blinkered way of misunderstanding their point.

Perhaps a modern example will help clarify. There is a French expression: Occupes-toi de tes oignons. Literally translated it means, Occupy yourself with your onions. Idiomatically, it means something like, “Mind your own business; don’t meddle in that which [Page 376]doesn’t concern you.” Now, imagine that a translator is confronted with this French phrase. How ought it to be rendered into English?

One could opt for a strictly literal translation: Occupy yourself with your onions. But what does this convey to an English reader? Very possibly nothing. Or one could opt for a more idiomatic translation: Mind your own business. This is better, but it lacks something of the playful irony of the original. The best translation for conveying the spirit of the original that I have come up with is, Mind your own beeswax.

But consider the problems this introduces: the term beeswax works only because it has humorous affinities for the English word business. Yet, without it, we miss some of the playfulness of the original. Would such a translation wrongly suggest that the Nephites had bees and beeswax, plus a word for business that was similar in sound to beeswax? Yet the association with bees is an artifact of the translation, and this problem crops up even when translating between two languages and cognitive systems as closely related as French and English.

If we opt instead for Mind your own business, then we have still introduced another term that has no analogue in the original. The French version invokes a tranquil agricultural image with onions, while the English has a more active commercial tinge with business. The lack of an informal second-person singular form in modern English introduces more difficulties in precisely capturing the sense: maybe we need Mind yer own beeswax. And so on.

One suspects Neville has never done any translation, or he would be aware of these kinds of difficulties. These sorts of issues are a constant theme of Gardner’s, who labors to understand this aspect of the translation, as Neville would know if he read Gardner with any attention or charity.19

The translation of the plates will involve at least the following steps:

- Nephite word for a direction is read;

- Translator discerns literal meaning of term;

- Translator discerns culturally understood meaning of the term;

- Translator chooses an English translation of the term (translator must ideally grasp both the literal meaning and the culturally understood meaning, though he may not);

- English reader must properly interpret the chosen English word.

[Page 377]No step is entirely straightforward and there is no perfect solution to the problem unless we insist that the Nephites thought and spoke about directions precisely as we do. But we know from our study of ancient cultures that many peoples did not. So on what grounds do we presume that the Nephites must have done so? Even a “perfect” translation (if such a thing exists) does not solve the fifth problem: we are not infallible readers or interpreters of the English text.

Even such a sequence can be difficult in modern English. Does a writer mean “magnetic north” or “celestial north” if she writes “north”? Or does she even know there is a difference and that it matters? As a Boy Scout in the northern Canadian latitudes, I was constantly cautioned about the difference when navigating over even short distances. The purposes for which one writer writes may not suit the needs or priorities of a reader. We can only work with what we’re given.

A more literal rendering of what was on the plates might make their meaning clearer to a specialist (like Gardner), while making the text less accessible to most readers — such a tradeoff might not be worth it. Or, conversely, the problem may be that in this case Joseph’s translation was more literal, not less. We might understand the scheme more clearly if he had glossed the term, rather than rendering it as the plate text had it. Perhaps the Nephites said east, and Joseph wrote east; the problem is in our unfamiliarity with how the Nephites understood the concept of east.20 Neville is also too hasty in presuming that the small plates of Nephi will necessarily use the same directional scheme (even if they use the same word for east) as Mormon’s abridgement written nearly a millennium later following much cultural and geographic movement from Lehi and Nephi’s Ancient Near East.

Sorenson has said that the cardinal directions might have been reoriented in the new world by the Nephites but by 1992 was characterizing this as a “suggestion.”21 By then, he was already offering other possible models drawing on indigenous cultural practices that resemble the more detailed schema offered by Poulsen.22 In 2013, Sorenson made reference to the Aztec habit of treating “the directions south, east, north, and west … not as distinct points, but as quadrants.”23 He also discusses similar schemes among the Quiché Maya, and concludes, “We can be sure that Nephite ‘north’ or ‘northward’ made reference to a direction, probably a quadrant, and that was an approximation of our north, although it did not match exactly what our term means.”24 Gardner has made similar observations, writing that Mesoamerican (and thus Nephite) “east is not a line toward the sun at the equinox, but the entire wedge created by [Page 378]tracing the passage of the sun along the horizon from solstice to solstice from the center.”25

In these matters, one need not think the Mesoamericanists are right in order to realize that Neville’s characterization is unfair and clearly prejudicial. It partakes of a double standard: Gardner, Sorenson, et al. are not permitted by Neville to have the Nephites see directions in the same way that the Maya did, even though the Maya represent a type of “host culture” in time and place for Book of Mormon events in their model. Neville insists that words like “north” and “west” must match “the ordinary meaning of the English language” and the cardinal directional scheme which we associate with them, instead of an adaptation of our system to translate a different but valid approach.

But, when confronted with the Mississippi river, Neville is quite happy to label part of it a “sea” through appeals to a few Jewish poetical texts. If Joseph Smith is bound to render directions just as the modern Neville thinks he should, we must also insist that the same Joseph Smith avail himself of perfectly good English words like “lake” and “river,” which are used on multiple occasions in the same volume. It can be nothing but special pleading to have one part of the Mississippi become the river Sidon, and another part a west sea, with a great lake labeled a second sea west for good measure. There is no common interpretive rule or principle that guides Neville’s exegesis — instead, he seems to pick and choose depending on the needs of the North American model.

Conclusion

I am reluctant to accept Neville’s chiastic argument based upon Alma 22:27 on at least three grounds: (1) the existence of the chiasmus is dubious; (2) assuming its presence in Neville’s reading leads to conclusions at variance with the Book of Mormon text, many of which make the actors’ military choices nonsensical; and (3) Neville’s reading requires him to make ad hoc assumptions and leaps at least as large as those he roundly condemns in others.

Neville’s production of a map and detailed explanation for how it was produced is a major step forward for Heartland advocates. Unfortunately, an examination of even a few verses reveals this model’s errors, ad hoc assumptions, and ignored details. These flaws suggest the need to begin again, and this would be best done via an internal model justified on its own terms without reference to any real-world location.[Page 379]

Endnotes

1. Jonathan Neville, Moroni’s America: The North American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Digital Legend, 2016). All references in the main text are to this work, unless otherwise noted. Neville also critiques articles with which he differs on a blog, opining that the peer review was inadequate: Interpreter Peer Reviews blog, http://interpreterpeerreviews.blogspot.ca.

2. Neville’s model is book length, and this review does not address the many defects I believe it contains. I here focus only on a single, core claim that seems, to me, emblematic of the model’s many lapses. Earlier reviews that have challenged Neville’s historical claims about Book of Mormon geography include: Matthew Roper, Paul Fields, Larry Bassist, “Zarahemla Revisited: Neville’s Newest Novel,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 17 (2016): 13–61; Matthew Roper, “John Bernhisel’s Gift to a Prophet: Incidents of Travel in Central America and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 16 (2015): 207–253; Matthew Roper, Paul J. Fields, and Atul Nepal, “Joseph Smith, the Times and Seasons, and Central American Ruins,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22/2 (2013): 84–97, online at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1525&context=jbms.

3. The parallelism has been previously noted in such sources as V. Garth Norman, Book of Mormon — Mesoamerican Geography: History Study Map (American Fork, UT: ARCON and AAF, 2006), 5; Joseph Lovell Allen and Blake Joseph Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Orem, UT: Book of Mormon Tours and Research Institute, 2008), 422–424; and Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, rev. ed. (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2011), 422–424. F. Richard Hauck has also referenced this purported chiasm in presentations. My thanks to Neal Rappleye for pointing out these earlier uses in other sources.

4. Donald W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007), 284–285 for Alma 22:27–34. Online at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/61/.

5. Donald W. Parry, personal correspondence with Gregory L. Smith, 30 November 2015, cited with permission, copy in my possession.

6. Figure 1: Neville’s internal geography based on Alma 22 (from Neville, p. 30).

7. John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Map (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 27, “Map 2: Chief Ethnic Areas.”

8. Basic Sorenson model (Mormon’s Map, 43, Map 5).

9. John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4/2 (1995): 8.

10. Nils Lund, Chiasmus in the New Testament (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1942), 41; cited in Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” 8n9.

11. Neville at times agrees with this, making it difficult to understand his model on this point (50).

12. This raises another difficulty with Neville’s model. He argues that the only mention of “narrow neck of land” is in Ether 10:20 (21–22), and so claims that Hagoth’s “narrow neck” is instead likely a different feature (54, 60, 186–89). He places Ether’s “narrow neck of land” near either modern Detroit or Buffalo (264), and thus 156–325 straight-line miles (250–520 km) from the shore of Lake Michigan. While it is understandable that he would attempt to distinguish the “narrow neck of land” from the “narrow neck” to save his model, this seems yet another ad hoc claim forcing a fit with North America. These issues require more attention than I can give them here, but the reader should realize that Neville’s model encounters such difficulties repeatedly.

13. Neville deals with some of these issues by proposing two “west” seas. I address these claims in detail in the section entitled “Two ‘West Seas’?”

14. Parry to Smith, 30 November 2015.

15. Jonathan Neville, “Seriously … this is the map you’re supposed to accept,” Book of Mormon Wars blog (18 August 2015), http://bookofmormonwars.blogspot.ca/2015/08/seriously-this-is-map-youre-supposed-to.html.

16. Jonathan Neville, “Comparison chart,” Book of Mormon Wars blog (9 December 2015), http://bookofmormonwars.blogspot.ca/2015/12/comparison-chart.html.

17. Jonathan Neville, “Peer Review of Brant Gardner trying to defend the Mesoamerican theory,” Book of Mormon Wars blog (4 March 2015), http://bookofmormonwars.blogspot.ca/2015/03/peer-review-of-brand-gardner-trying-to.html.

18. Neville, “Peer Review of Brant Gardner trying to defend the Mesoamerican theory.”

19. Brant Gardner, The Gift and Power: Translating the Book of Mormon (Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 137–283. See also Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 Vols. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:2–9. Throughout the latter six volumes, Gardner is frequently at pains to explain how he sees the relationship between plate text and English translation.

20. See Brant A. Gardner, “From the East to the West: The Problem of Directions in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 3 (2013): 152–53, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/from-the-east-to-the-west-the-problem-of-directions-in-the-book-of-mormon/

21. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co.; Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1996 [1985]), 39–40. Compare with The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, UT: FARMS, revised edition, 1992), 405–406, 414.

22. Lawrence Poulsen, “Directions in the Book of Mormon,” (accessed 15 September 2015), http://bomgeography.poulsenll.org/bomdirections.html and “Book of Mormon Geography,” paper presented at the FAIR [now FairMormon] Conference, August 2008, 18–28, http://www.fairmormon.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/2008-Larry-Poulsen.pdf. Compare with Sourcebook, 409–412.

23. Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company with Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 124. See also 299–300 for another discussion of the idea.

24. Mormon’s Codex, 125, 127.

25. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 132.

Go here to see the 13 thoughts on “““From the Sea East Even to the Sea West”: Thoughts on a Proposed Book of Mormon Chiasm Describing Geography in Alma 22:27”” or to comment on it.