The following essay was presented on 3 August 2012 as “Of ‘Mormon Studies’ and Apologetics” at the conclusion of the annual conference of the Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (FAIR) in Sandy, Utah. It represents the first public announcement and appearance of Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture, which had been founded only slightly more than a week earlier, on 26 July. In my view, that rapid launch was the near-miraculous product of selfless collaboration and devotion to a cause on the part of several people—notable among them David E. Bokovoy, Alison V. P. Coutts, William J. Hamblin, Bryce M. Haymond, Louis C. Midgley, George L. Mitton, Stephen D. Ricks, and Mark Alan Wright—and I’m profoundly grateful to them. This essay, which may even have some slight historical value, is something of a personal charter statement regarding that cause. It is published here with no substantial alteration.

Founded in California in 1979 by John W. Welch, FARMS, or the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, became part of Brigham Young University in 1997.

It did so at the invitation of President Gordon B. Hinckley, who remarked at the time that “FARMS represents the efforts of sincere and dedicated scholars. It has grown to provide strong support and defense of the Church on a professional basis. I wish to express my strong congratulations and appreciation for those who started this effort and who have shepherded it to this point.”

[Page ii]Plainly, FARMS had gained a reputation for doing apologetics, though it must be said that apologetics was never its sole focus. It has always fostered scholarship that cannot plausibly be characterized as apologetic; Professor Royal Skousen’s meticulous, landmark work on the text and textual history of the Book of Mormon is perhaps the most notable example of such scholarship, but it’s far from alone.

Our official motto, though, was drawn from Doctrine and Covenants 88:118: “By study and also by faith.”

In his essay “Advice to Christian Philosophers,” Alvin Plantinga of the University of Notre Dame, indisputably among the preeminent Christian philosophers of our time, argued that “we who are Christians and propose to be philosophers must not rest content with being philosophers who happen, incidentally, to be Christians; we must strive to be Christian philosophers.”1 Elder Neal A. Maxwell exhorted Latter-day Saint academics in much the same spirit: “The LDS scholar has his citizenship in the Kingdom,” he said, “but carries his passport into the professional world—not the other way around.”

However inadequately, we who were affiliated with FARMS from its early years tried to work and to act in that spirit.

In 2006, much to our delight and (though we had requested the change) to our surprise, the organization was rechristened as the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. Elder Maxwell had always been an enthusiastic supporter of our work and personally interested in it; his passing, two years before, had saddened us, and others, enormously.

At the dinner during which the new name was formally announced, President Boyd K. Packer, of the Quorum of the Twelve praised two specific aspects of the Institute’s work: the Islamic Translation Series and the Institute’s defense of the Kingdom. It was very much in the spirit of Elder Maxwell [Page iii]himself, who wanted to permit critics of the Church “no more uncontested slam dunks.”

As recently as 21 April 2010, the Maxwell Institute’s Mission Statement positioned the organization as “Describ[ing] and defend[ing] the Restoration through highest quality scholarship” and “Provid[ing] an anchor of faith in a sea of LDS Studies.”2

In a posthumous tribute to his friend C. S. Lewis, the English philosopher and theologian Austin Farrer wrote a passage that became a favorite of Elder Maxwell’s, and that Elder Maxwell used on several public occasions. It also served for many years as a kind of unofficial motto for several of us who were involved with, first, FARMS and, then, its successor organization, the Maxwell Institute:

Though argument does not create conviction, lack of it destroys belief. What seems to be proved may not be embraced; but what no one shows the ability to defend is quickly abandoned. Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish.3

In referring to such “argument,” Austin Farrer had in mind what is commonly called—very commonly among Catholics and Evangelicals, though far less commonly among Latter-day Saints—apologetics.

Derived from the Greek word απολογία (“speaking in defense”) apologetics is the practice or discipline of defending a position (usually, but not always, a religious one) through the use of some combination or other of evidence and reason. In modern English, those who are known for defending their positions (often minority views) against criticism or attack are [Page iv]frequently termed apologists.4 In my remarks today, I’ll be using the word apologetics to refer to attempts to prove or defend religious claims. But the fact is that every argument defending any position, even a criticism of Latter-day Saint apologetics, is an apology. “By itself, ‘apologist’ does not tell whether the cause is noble or disreputable.”5

Some people turn their noses up at the thought of apologetics. As Richard Lloyd Anderson notes, being called an “apologist” is commonly “a put-down, meaning one who trashes truth.”6 “ ‘Apologetics,’ ” writes Paul J. Griffiths, currently Warren Professor of Catholic Thought at the Divinity School of Duke University,

has . . . become a term laden with negative connotations: to be an apologist for the truth of one religious claim or set of claims over against another is, in certain circles, seen as not far short of being a racist. And the term has passed into popular currency, to the extent that it has, as a simple label for argument in the service of a predetermined orthodoxy, argument concerned not to demonstrate but to convince, and, if conviction should fail, to browbeat into submission.7

“In almost all mainstream institutions in which theology is taught in the USA and Europe,” Griffiths reports,

[Page v]

apologetics as an intellectual discipline does not figure prominently in the curriculum. You will look for it in vain in the catalogues of the Divinity Schools at Harvard or Chicago; liberal Protestants have never been wedded to the practice of interreligious apologetics, and while the Roman Catholic Church has a long and honorable tradition of apologetics, interreligious and other, its approach to theological thinking about non-Christian religious communities has moved far from the apologetical since the Second Vatican Council, and especially since the promulgation of the conciliar document Nostra Aetate.8

Apologists, some critics declare, are not concerned with truth; what apologists do isn’t real scholarship, and anyhow, as one hostile Internet apostate put it, apologetics is “a fundamentally unethical and immoral enterprise.” Or, alternatively, in the words of another anonymous Internet ex-Mormon, “Each of us is either a man or woman of faith or of reason. . . . All apologetics is, is faux logic, faux reason designed to lure the wonderer back into the fold. Those of faith are threatened by defectors to reason.” “Apologists,” he continued in a subsequent post,

try to shill an explanation to questioning members as though science and reason really explain and buttress their professed faith. It [sic] does not. By definition, faith is the antithesis of science and reason. Apologetics is a further deception by faith peddlers to keep power and influence.

I’m willing to wager, by the way, that although these critics want believers to stop responding, they do not intend to stop criticizing. There is no question that any team will score more easily if the opposing team’s defensive players leave the field, [Page vi]but I’m unaware of any athlete with the chutzpah to make the request.

But this attitude seems, anyway, to reflect a fundamental misunderstanding—like any other form of intellectual enterprise, apologetics can be done competently or incompetently, logically or illogically, honestly or not—and it certainly ignores the venerable tradition of apologetics, which has enlisted some very notable writers, scholars, and thinkers (e.g., Socrates/Plato, St. Justin Martyr, Origen of Alexandria, St. Augustine, al-Ghazālī, Ibn Rushd [Averroës], Moses Maimonides, St. Anselm, St. Thomas Aquinas, Hugo Grotius, John Locke, John Henry Newman, G. K. Chesterton, Ronald Knox, C. S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, Richard Swinburne, Alvin Plantinga, Peter Kreeft, Stephen Davis, N. T. Wright, and William Lane Craig). It’s dubious (at best) to summarily dismiss these people or their apologetic writings as “fundamentally unethical and immoral” and flatly irrational. Within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, although the term has rarely been used, there has been apologetic activity from the very beginning. (The brothers Parley and Orson Pratt, Oliver Cowdery, Orson Spencer, John Taylor, B. H. Roberts, and Hugh Nibley represent some of the high points.)

Still, a few faithful members of the church profess to disdain apologetics as well.

Some, for instance, seem to believe it inherently evil. They appear to use the word apologetics to mean “trying to defend the church but doing so badly,” whether through incompetence, dishonesty, or mean-spiritedness. But, again, apologetics, as such, is a value-neutral term. Just like historical writing, carpentry, and cooking, apologetics can be done well or poorly. Apologists, like attorneys and scientists and field laborers, can be pleasant or unpleasant, humble or arrogant, honest or dishonest, fair or unfair, civil and polite, or nasty and insulting.

[Page vii]The very recent decision by the current leadership of the Maxwell Institute to forego explicit defense and advocacy of Mormonism—to renounce explicit apologetics—may have been influenced by concerns about the arrogant mean-spiritedness of one or two of those most prominently associated with its apologetic side. But, from what I can tell—and I’ll freely admit that I and others have found explanations of the Institute’s announced “new course” somewhat inscrutable—it seems certain that the principal factor was a desire to become more purely “academic,” and to reconceive its audience as not merely including professional scholars but as primarily if not exclusively composed of full-time academics and academic libraries.

Whereas, much earlier, FARMS had been encouraged by a prominent Church leader not to forget “the Relief Society sister in Parowan,” the Maxwell Institute’s new audience has been expressly said not to include “the typical Mormon in Ogden.”

“The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship,” says the Institute’s public announcement that it had dismissed the editors of the Mormon Studies Review (or FARMS Review) and suspended publication of that journal, “is continually striving to align its work with the academy’s highest objectives and standards, as befits an organized research unit at Brigham Young University. . . . We are going to assemble a group of scholars in the area of Mormon studies to consult with us on how best to position Mormon Studies Review within this area of study.”

So what is “Mormon studies”? What is this field in which the new Mormon Studies Review, when and if it reappears after a suitably long period of detoxification, is going to better position itself?

“The term Mormon studies means different things to different people,” M. Gerald Bradford, the current director of the Maxwell Institute, wrote in an article published by the FARMS Review in 2007. “For some . . . it is synonymous with Mormon historical studies. . . . I use the term to refer to a range of efforts [Page viii]likely to contribute directly to work on the tradition in various religious studies programs.”9

Mormon studies, it seems, is a subset of the broader field of “religious studies.” But what is this field of “religious studies”?

On the whole, it’s quite different from the way in which Brigham Young University has historically approached Mormonism. “In the wider academic world,” writes Dr. Bradford,

within religion programs in private, nonaffiliated, and public colleges and universities, such study is conducted in a diverse intellectual environment. At BYU the subject is approached from a perspective of institutional and individual commitment. While BYU does offer a few courses on other religions, it does not maintain a religious studies program. It is devoted, in other words, to teaching students the “language of faith” more than the “language about faith.”10

“It proceeds,” he says of religious studies, “on the basis of maintaining a distinction between descriptive and structural studies on the one hand and attempts at grappling with religious value judgments and truth claims on the other.”11 It constitutes “an important and influential alternative to theological approaches that have been, and continue to be, the way religion is most often studied and taught in this country.”12 In religious studies, says Dr. Bradford, “before attempting to resolve questions of truth or value, the goal should be to show the influence and power of these ideas and practices in the real world and to discern how they interact with other aspects of human [Page ix]existence.”13 Thus, there should be no surprise that, in Dr. Bradford’s lengthy FARMS Review article entitled “The Study of Mormonism: A Growing Interest in Academia,” strikingly little attention—indeed, almost none—is given to apologetics.14

“Fundamentally,” observes my friend and colleague William Hamblin, who has published extensively on Islam, ancient holy warfare, and Solomon’s temple in myth and history,

religious studies examines religion as a human phenomenon, with the (often unspoken) assumption that religious belief and practice is entirely explainable without positing the existence of God or his intervention in human history and life. This is a self-imposed limitation on the discipline, in which it is mimicking . . . the empiricism and materialism of the natural sciences. This assumption makes some sense in some ways, since religion is indeed an integral part of of all human societies and cultures, and can be studied by examining its human context and its impact on human cultures, societies, and individuals.15

A couple of almost randomly chosen religious studies programs should serve to illustrate the orientation of the field:

The website of the religious studies program at Utah Valley University, in Orem, explains that

The program is intended to serve our students and community by deepening our understanding of religious beliefs and practices in a spirit of open inquiry. Its aim is neither to endorse nor to undermine the claims of religion, but to create an environment in [Page x]which various issues can be engaged from a variety of perspectives and methodologies.16

A corresponding entry for the religious studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill informs students that

Writing for religious studies takes place within a secular, academic environment, rather than a faith-oriented community. For this reason, the goal of any paper in religious studies should not be to demonstrate or refute provocative religious concepts, such as the existence of God, the idea of reincarnation, or the possibility of burning in hell. By nature, such issues are supernatural and/or metaphysical and thus not open to rational inquiry.17

In this light, notice how the 2012 Mission Statement of the Maxwell Institute reads, and contrast it with the one I quoted above from 2010:

By furthering religious scholarship through the study of scripture and other texts, Brigham Young University’s Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship seeks to deepen understanding and nurture discipleship among Latter-day Saints while promoting mutual respect and goodwill among people of all faiths.”

“Understanding” will be “deepened” through “the study of scripture and other texts”—some of these other texts being those of the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, which I conceived and founded and which deals with such materials as the Physics of Ibn Sina, Moses Maimonides’ Medical Aphorisms, and The Incoherence of the Philosophers by al-Ghazali. “Scholarship” [Page xi]will also, the Statement indicates, “nurture discipleship among Latter-day Saints.”

Gone is the language about “defend[ing] the Restoration” and “provid[ing] an anchor of faith in a sea of LDS Studies.” The focus, now, is on “how best to position Mormon Studies Review [and, presumably, the Maxwell Institute as a whole] within this area of study.”

It’s been explained to me and a few others that, in fact, the Maxwell Institute will continue to do apologetics, in the sense that solid scholarship will create a favorable impression in the minds of the scholars who read it. But this seems to stretch the meaning of the term apologetics well beyond customary bounds. Fielding a successful football team and hiring an effective grounds crew to keep the flowers blooming on BYU’s campus also tend to make favorable impressions upon outsiders, and I support them, but they don’t seem in any real sense “apologetic.”

One enthusiastic proponent of Mormon studies has pointed out what should be obvious, given the general nature of the broader field of religious studies, that “those engaged in Mormon studies do not necessarily have to be Mormon themselves.”18

Let me say right away that I believe there is a place for such studies. I, myself, in my writing on Islam, work from within a similar methodology. And I don’t object to such approaches when the topic is Mormonism. That’s why I’m currently serving as president of the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, which actively involves non-Mormon and—how can I say this without given offense where none is intended?—non-communicant Mormon scholars as well as believing Mormon scholars in its conferences and its journal and on its board.

[Page xii]In fact, during the last conversation that I had with the director of the Maxwell Institute before I left for six weeks overseas—I was dismissed by email roughly a week into my trip, while in Jerusalem—I was informed of the new course to which the Maxwell Institute is now committed. To illustrate what the “new course” might look like, three volumes recently published by a new Mormon-oriented venture called Salt Press were offered to me as prime examples of the kind of writing that the Institute ought to be sponsoring. As it happens, I agree that that’s the kind of thing we should have been sponsoring. In fact, I serve on Salt Press’s Editorial Board.

I see no reason why both apologetics and Mormon studies shouldn’t be encouraged, nor even why they can’t both be pursued by the same organization, published in the same journal, cultivated by the same scholar. There is, I believe, a place for both.

I see apologetics as a form, a subgenre, of Mormon studies. If I didn’t, I would never have permitted the renaming of the FARMS Review as the Mormon Studies Review, because that name change would have represented a fundamental change of mission for the journal—as, in fact, I’m now informed that it did.

I’m for inclusion, rather than exclusion. But there can be no question that Mormon studies, as it’s conceived in secular academic programs, is quite distinct from apologetics or “defense of the faith.” And, unlike me, some see the two approaches as utterly incompatible, one being academically legitimate and the other not—just as the kind of religious education practiced at BYU would be disdained at many colleges and universities.

A few observers, commenting on the recent shake-up at the Maxwell Institute, have claimed that it represents a generational change: A newer, perhaps better trained, certainly kinder and gentler cohort of scholars is arriving on the scene that is embarrassed if not disgusted by the things their [Page xiii]predecessors have done, and that is eager to replace sordid polemics and distasteful pseudo-scholarship with solid, dispassionate Mormon studies. Time will tell whether this change of generations will really bring the predicted transformation. But it’s demonstrably untrue that academic discomfort with apologetics is a novelty, without precedent. Hugh Nibley, widely venerated now, was reviled and resented by some of his fellow Latter-day Saint academics not so very long ago.

Richard Lloyd Anderson, one of our most distinguished Latter-day Saint scholars and the premier authority on the Witnesses to the Book of Mormon, told me many years ago of being labeled early in his career by fellow Mormons as an apologist rather than a real scholar. “Today,” he has told me in a private email

Latter-day Saint scholars are rescuing “apologist” from the trash bin, but it probably will continue as a standard sneer in uninformed circles. I would rather not be so described, but I am convinced intellectually and spiritually that Joseph Smith was authorized by angels to restore Christ’s Original Church. Rather than feel insulted by a misused label, I keep paradoxical satisfaction that the ancient and millennial gospel of light has caused me to be exiled to intellectual outer darkness. Yet the Lord promised his ancient Twelve: “Whosoever therefore shall confess me before men, him will I confess also before my Father which is in heaven” (Matt. 10:32).

This conflict will not soon end. But I still will hope for more accurate descriptions. My thesaurus lists “advocate” as a synonym for “apologist.” These terms have few differences in objective meaning, but the connotative distinction for me is very meaningful.19

[Page xiv]I’m not sure, unfortunately, that Latter-day Saint scholars have rescued the term apologist from the trash bin, as Professor Anderson says. I haven’t given up hope, but I’m not sure that we’ll be able to do it.

In an article entitled “Where is the ‘Mormon’ in Mormon Studies?” that appeared in the 2011 inaugural issue of the Claremont Journal of Mormon Studies, Loyd Ericson, a proponent of Mormon studies who has been vocally overjoyed at recent changes—both of direction and of personnel—at the Maxwell Institute, suggested that some people might need to be excluded from the field of Mormon studies. We’re “force[d] . . . to ask the questions,” he wrote, “of who should be allowed to participate, how should it be done, and what should be the objects of these studies. Should boundaries of exclusion be drawn? Or should all—including the evangelizing, the apologists, the revisionists, and the anti-Mormons—be allowed to mingle in the broadest field of Mormon Studies?”20

Of “the Mormon apologists”—who, he wrote under quite different circumstances back in 2011, are “easily best represented by Daniel Peterson and his colleagues in the Maxwell Institute at Brigham Young University”—Ericson cautions that “While they may at least seem to work within academic standards, there still exists an uneasiness among many about including them into Mormon Studies because of the belief of many academics that Mormon and/or religious studies is a forum for studying, and not promoting or defending, religious beliefs.”21

Ericson allowed, hypothetically, that there might be a “uniquely Mormon methodology” that one could employ in Mormon studies. “This methodology,” he says,

[Page xv]

would include a faith or religiously based testimonial as part of one’s argument or discussion. Examples of this might include appealing to one’s own spiritual confirmation of the historical reality of Joseph Smith’s First Vision when discussing the beginnings of Mormonism, basing an understanding of the context of the Book of Mormon off of one’s belief in its ancient origins, or the claim that the growth of the LDS Church is due to the Holy Spirit influencing others to convert to God’s true church.22

His statement is fascinating. Notice how it equates “appealing to one’s own spiritual confirmation of the historical reality of Joseph Smith’s First Vision when discussing the beginnings of Mormonism” and “claim[ing] that the growth of the LDS Church is due to the Holy Spirit” with “basing an understanding of the context of the Book of Mormon off of one’s belief in its ancient origins.” All of these are subsumed under the notion of “includ[ing] a faith or religiously based testimonial as part of one’s argument or discussion.”

One’s personal spiritual experiences would never constitute appropriate or acceptable evidence in an academic argument, however appropriate they surely are in church, and FARMS and Maxwell Institute authors have never appealed to them in that way. Nor would it be suitable to claim, in a purely secular academic argument, that the Holy Spirit is the cause of any religious trend or event. Methodological naturalism reigns supreme in the general academic world, and for good reason.

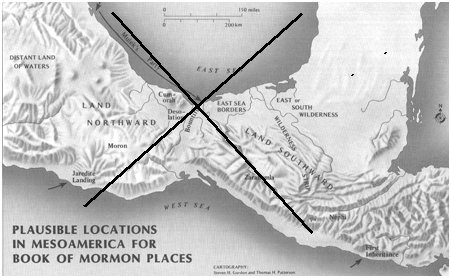

But an important element in the FARMS and Maxwell Institute approach, certainly a facet of the approach taken by many authors, has been to presume the antiquity of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, and the like, or at least to [Page xvi]consider ancient settings. We wanted to see what can be learned about the texts on that basis, to get an idea of how productive such a viewpoint is. Moreover, Hugh Nibley, the patron saint of FARMS, argued at length in such essays as “New Approaches to Book of Mormon Study,” which first appeared in 1953 and was then incorporated into his Collected Works via the 1989 anthology The Prophetic Book of Mormon, that the proper way to examine the provenance of a disputed text is, first, to assume that it’s genuine. He quotes the eminent German scholar Friedrich Blass: “We have the document, and the name of its author; we must begin our examination by assuming that the author indicated really wrote it.”23

In an online exchange with me back in 2010, Loyd Ericson argued that any apologetic effort attempting to defend the antiquity of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, and the Book of Abraham inescapably makes faulty assumptions about the verifiability of those texts. Why? Because the versions of these scriptures that we have today are in English and date from the nineteenth century, and because we do not possess (and, hence, cannot examine) the putative original-language texts from which they are claimed to have been translated. Accordingly, he said, they cannot plausibly be read, used, tested, or analyzed as ancient historical documents. They can only be read as documents of the nineteenth century, as illustrations of, and in the light of, that period. This, he claimed, is an insurmountable problem.

But, as I argued in an essay published in the late FARMS Review in 2010, it isn’t. Scholars routinely test the claims to historicity of translated documents for which no original-language manuscripts are extant and, also routinely, having [Page xvii]satisfied themselves of their authenticity, use them as valuable scholarly resources for understanding the ancient world.24

A few members of the Church appear to reject apologetics in principle, regarding it as inevitably, no matter how charitably and competently it is done, more detrimental than beneficial. They seem to do so on the basis of something resembling fideism, the view that faith is independent of reason, and even that reason and faith are incompatible with each other. “The words reasoning and evidence trouble me,” one active Church member said to me during an Internet discussion. They seem, he said,

to imply that things like Hebraisms and the NHM inscription will validate my commitment to Mormonism. This is absolutely and patently untrue and false. Reasoning and so-called evidences are illusions, in a world that requires faith. There is no rationale for angels, gold plates, and a corporeal Divine visit(s). There is no rationale for a resurrection, atonement, or exaltation. These things defy reason and logic. There is no possible evidence for these things either. My faith, my redemption, my happiness/peace are the reasons and evidence for my devotion.

Now, obviously, to treat God solely as a hypothesis, a conjecture, or a topic for discussion is very different from reverencing or submitting to God in a spirit of religious devotion. There are few if any for whom reason is sufficient without faith. Ideally, from the believer’s perspective, God comes to be known in a personal I-Thou relationship, as an experienced challenge and as a comfort in times of sorrow, not merely as a chance to show off in a graduate seminar or, worse, to grandstand on an Internet message board. And many of those who know God in that way—certainly this must be true of simple, unlettered [Page xviii]believers across Christendom and throughout its history—may neither need nor desire any further evidence. Moreover, most would agree—I certainly would—that it is impossible, using empirical methods, to prove the divine. And it is surely true that faith is best nurtured and sustained, not by immersion in clever arguments, but by the method outlined in Alma 32. Emulation of the Savior, loving service, faithful home and visiting teaching, generous fast offerings, earnest missionary work, prayerful communication—these are the fundamentally significant elements of a Christian life. There are relatively few people for whom apologetics is a necessary, let alone a sufficient, path to faith.

For the vast majority of people, today as in premodern times, faith isn’t a matter of reason or argumentation, but of hearing the testimonies of others and of coming to conviction on the basis of personal experiences. Each Fast Sunday, Latter-day Saints are privileged to hear often beautiful testimonies that offer neither syllogisms nor objective data. Missionaries quickly discover that it is testimony that changes hearts, not chains of scriptural references, let alone a weighty volume of apologetics.

But that is not to admit that evidence and logic are wholly irrelevant to religious questions. Apologetics is no mere luxury or game. Someone who has been confused and bewildered by the sophistry of antagonists—and often, though not always, that is exactly what it is—might well justly regard apologetic arguments as a vital lifeline permitting the exercise of faith, as a way (in the words of one message board poster) of “keeping a spark going long enough to rekindle a fire.” Testimony can see a person through times when the evidence seems against belief, but studied conviction can help a believer through spiritual dry spells, when God seems distant and spiritual experiences are distant memories. Even faithful members who are [Page xix]untouched by crisis or serious doubt can be benefited by solid apologetic arguments, motivated to stand fast, to keep doing the more fundamental things that will build faith and deepen confidence and strengthen their all-important spiritual witness. Why should such members be deprived of this blessing?

“I am well aware,” says the Oxford philosophical theologian Brian Hebblethwaite in the very first paragraph of his 2005 book In Defense of Christianity,

that reason is not the basis of faith. Christian faith is not founded on arguments. Most believers have either grown up and been nurtured in what have been called “convictional communities” and have simply found that religious faith and participation in religious life make sense to them, or else have been precipitated into religious commitment and practice by some powerful conversion experience. Few people are actually reasoned into faith. The arguments which I intend to sketch here are more like buttresses than foundations, reasons that can be given, as I say, in support of faith.25

I like that image of foundation and buttresses.

Furthermore, in my judgment, that active Church member is simply wrong. There is, in fact, a rational case to be made for such propositions as the actual existence of the gold plates of the Book of Mormon and the resurrection of Christ.26

[Page xx]Will apologetic arguments save everybody? No. The Savior himself aside, nothing will—and, in fact, at least a few determined souls will apparently forgo salvation despite even his gracious atonement. But the fact that some remain unmoved by them no more discredits apologetic arguments as a whole than the enterprise of medicine is rendered worthless by the fact that some patients don’t recover. Certain illnesses are fatal.

The children of God have different temperaments, expectations, capacities, personal histories, interests, and paths, and we dare not, or so it seems to me, close a door on someone’s journey that, though perhaps unnecessary to us, might be invaluable for that person. The fact that I can swim scarcely justifies my standing on the shore watching while someone else drowns because she can’t. As C. S. Lewis put it, speaking of and to well-educated British Christians,

To be ignorant and simple now—not to be able to meet the enemies on their own ground—would be to throw down our weapons, and to betray our uneducated brethren who have, under God, no defence but us against the intellectual attacks of the heathen. Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.27

If the ground is encumbered with a lush overgrowth of critical arguments, the seed of faith of which Alma speaks cannot take root. It’s the duty of the apologist, in that sense, [Page xxi]to clear the ground in order to make it possible for the seed to grow. Faith is still necessary. (I’m unaware of anybody who claims that religious belief derives purely from reason; for that matter, I’m confident that unbelief doesn’t, either.) Apologetics is simply a useful tool that, much as Austin Farrer wrote, helps to preserve an environment that permits such faith to take root and flourish.

“Be ready,” says the First Epistle of Peter, “always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in you with meekness and fear” (1 Peter 3:15). That’s the King James Version rendering of the passage. “Always be prepared,” reads the New International Version, “to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.” The Greek word rendered “answer” in both translations is apologia, which is manifestly cognate with the English word apologetics.

A skeptic of apologetics might, of course, respond that the author of 1 Peter is telling Christians to be willing to testify of Christ and their hope for salvation, something quite distinct from a call to use reason to defend a particular religious claim. And, obviously, the biblical apostles would indeed want us to stand as witnesses for Christ. But does 1 Peter 3:15 exclude the use of rational argument in such testifying?

It seems highly unlikely. The word that is translated as “reason” by both the King James Version and the New International Version, cited above, is the Greek λογος, or logos. It is an extraordinarily rich term, and much has been written about its meaning.28 Logos can refer to speech, a word, a computation or reckoning, the settlement of an account, or the independent personified “Word” of God (as in most translations of John 1:1). A central meaning, however, is “reason,” and it is from logos [Page xxii]that the English word logic derives—as do the names of any number of fields devoted to systematic, rational inquiry (e.g., anthropology, archaeology, biology, cosmology, criminology, Egyptology, geology, meteorology, ontology, paleontology, theology, and zoology). It is rendered in the Latin Vulgate Bible’s version of 1 Peter 3:15 as ratio (“reason,” “judgment”), which is obviously related to our English word rational. Furthermore, when Paul spoke before King Agrippa at Caesarea Maritima—arguing that, among other things, Christ’s resurrection fulfilled the predictions of Moses and the other prophets—he was making his “defense,” and he used a Greek verb closely and directly related to apologia: apologeisthai. The Apology of Plato, similarly, reports the speech that Socrates offered before his Athenian accusers.

It seems that 1 Peter’s exhortation to “be ready always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in you” charters and legitimates the use of reasoned argument in support of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Frankly, the idea that active Latter-day Saints might (or even should) feel no obligation to use what they know in order to defend the church against its critics, or to help struggling Saints, strikes me as exceedingly strange. Our responsibility as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to love and serve the Lord with all our heart, might, mind, and strength implies such an obligation, and our temple covenants absolutely entail that we sustain and defend the kingdom of God.29

In a sense, the scholar, thinker, teacher, or writer who places his or her skills on the altar as an offering to God is no different from the bricklayer, knitter, carpenter, counselor, administrator, dentist, accountant, youth leader, farmer, physician, linguist, genealogist, or nurse who donates time and labor and [Page xxiii]specific abilities in the service of God and the Saints and humanity in general.

Now the body is not made up of one part but of many. If the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. And if the ear should say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? But in fact God has arranged the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. If they were all one part, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, but one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I don’t need you!” And the head cannot say to the feet, “I don’t need you!” (1 Corinthians 12:14–21, NIV)

As C. S. Lewis put it, “All our merely natural activities will be accepted, if they are offered to God, even the humblest, and all of them, even the noblest, will be sinful if they are not.”30

Now, one might conceivably argue that while, as a Christian, one is under a divine mandate to bear witness, one is not obliged to use reason to defend specific truth claims, or that, whatever covenants they may have taken upon themselves, Latter-day Saints are not obligated to defend their specific church by the use of such rational arguments as they can muster.

The scriptures, however, seem to teach otherwise. Jesus himself, for example, appealed to miracles and to fulfilled prophecy as evidence that his claims were true. To his disciples, he said, “Believe me that I am in the Father, and the Father in me: or else believe me for the very works’ sake” (John 14:11). To [Page xxiv]the two Christian disciples walking along the road to Emmaus immediately after his resurrection, he said: “O fools, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken: Ought not Christ to have suffered these things, and to enter into his glory? And beginning at Moses and all the prophets, he expounded unto them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:25–27).

Speaking to other Jews, the original Christian apostles likewise employed fulfilled prophecy and the miracles of Jesus—particularly his resurrection—to demonstrate that Jesus was the Messiah. Consider, for example, how, in his sermon on the day of Pentecost, Peter appeals to all three:

Men of Israel, listen to this: Jesus of Nazareth was a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs, which God did among you through him, as you yourselves know. This man was handed over to you by God’s set purpose and foreknowledge; and you, with the help of wicked men, put him to death by nailing him to the cross. But God raised him from the dead, freeing him from the agony of death, because it was impossible for death to keep its hold on him. David said about him:

I saw the Lord always before me.

Because he is at my right hand,

I will not be shaken.

Therefore my heart is glad and my tongue rejoices;

my body also will live in hope,

because you will not abandon me to the grave,

nor will you let your Holy One see decay.

You have made known to me the paths of life;

you will fill me with joy in your presence.

[Page xxv]Brothers, I can tell you confidently that the patriarch David died and was buried, and his tomb is here to this day. But he was a prophet and knew that God had promised him on oath that he would place one of his descendants on his throne. Seeing what was ahead, he spoke of the resurrection of the Christ, that he was not abandoned to the grave, nor did his body see decay. God has raised this Jesus to life, and we are all witnesses of the fact. (Acts 2:22–32, NIV)

In dealing with non-Jews, the apostles attempted to demonstrate the existence of God by appealing to evidence of it in nature. Thus, for instance, in Acts 14, when the pagans at Lystra were so impressed by the miracles of Barnabas and Paul that they mistook them for, respectively, Zeus and Hermes, the two apostles were horrified.

They rent their clothes, and ran in among the people, crying out, and saying, Sirs, why do ye these things? We also are men of like passions with you, and preach unto you that ye should turn from these vanities unto the living God, which made heaven, and earth, and the sea, and all things that are therein: who in times past suffered all nations to walk in their own ways. Nevertheless he left not himself without witness, in that he did good, and gave us rain from heaven, and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness. (Acts 14:14–17)

Addressing the saints at Rome, Paul declared that

the wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of men who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the [Page xxvi]world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse. (Romans 1:18–20, NIV)

Such appeals to the evidence of nature are also found in the Old Testament: “The heavens declare the glory of God,” says the Psalmist; “the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Psalm 19:1, NIV). Historical evidence also plays a role. Addressing the Saints at Corinth, the apostle Paul ticks off a list of witnesses to the resurrection of Jesus as evidence for the truth of what they have been taught:

For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also. (1 Corinthians 15:3–8, NIV)

During his stay in Athens, Paul “reasoned in the synagogue with the Jews and the God-fearing Greeks, as well as in the marketplace day by day with those who happened to be there” (Acts 17:17, NIV). And, most notably, he presented a logical case to some of the city’s Epicurean and Stoic philosophers on Mars Hill, near the Acropolis, even citing proof texts from pagan Greek poets in support of his doctrine (Acts 17:18–34).

It’s clear that both Jesus and the apostles were perfectly willing to supply evidence and to make arguments for the truth of the message they preached. Did this mean that they didn’t trust the Holy Ghost to bring about conversion? Hardly. [Page xxvii]Instead, they trusted that the Holy Ghost would work through their arguments and their evidence to convert those whose hearts were open to the Spirit.

Moreover, according to the Book of Mormon, a similar mixture of preaching, testifying, and appealing to reason was employed by the inspired leaders of the pre-Columbian New World. Consider the case of the antichrist called Korihor:

And he did rise up in great swelling words before Alma, and did revile against the priests and teachers, accusing them of leading away the people after the silly traditions of their fathers, for the sake of glutting on the labors of the people. Now Alma said unto him: Thou knowest that we do not glut ourselves upon the labors of this people; for behold I have labored even from the commencement of the reign of the judges until now, with mine own hands for my support, notwithstanding my many travels round about the land to declare the word of God unto my people. And notwithstanding the many labors which I have performed in the church, I have never received so much as even one senine for my labor; neither has any of my brethren, save it were in the judgment-seat; and then we have received only according to law for our time. And now, if we do not receive anything for our labors in the church, what doth it profit us to labor in the church save it were to declare the truth, that we may have rejoicings in the joy of our brethren? Then why sayest thou that we preach unto this people to get gain, when thou, of thyself, knowest that we receive no gain? (Alma 30:31–35)

Alma even appeals to a simple kind of natural theology to make his point:

[Page xxviii]

And then Alma said unto him: Believest thou that there is a God? And he answered, Nay. Now Alma said unto him: Will ye deny again that there is a God, and also deny the Christ? For behold, I say unto you, I know there is a God, and also that Christ shall come. And now what evidence have ye that there is no God, or that Christ cometh not? I say unto you that ye have none, save it be your word only. But, behold, I have all things as a testimony that these things are true; and ye also have all things as a testimony unto you that they are true; and will ye deny them? Believest thou that these things are true? Behold, I know that thou believest, but thou art possessed with a lying spirit, and ye have put off the Spirit of God that it may have no place in you; but the devil has power over you, and he doth carry you about, working devices that he may destroy the children of God. And now Korihor said unto Alma: If thou wilt show me a sign, that I may be convinced that there is a God, yea, show unto me that he hath power, and then will I be convinced of the truth of thy words. But Alma said unto him: Thou hast had signs enough; will ye tempt your God? Will ye say, Show unto me a sign, when ye have the testimony of all these thy brethren, and also all the holy prophets? The scriptures are laid before thee, yea, and all things denote there is a God; yea, even the earth, and all things that are upon the face of it, yea, and its motion, yea, and also all the planets which move in their regular form do witness that there is a Supreme Creator. And yet do ye go about, leading away the hearts of this people, testifying unto them there is no God? And yet will ye deny against all these witnesses? And he said: Yea, I will deny, except ye shall show me a sign. And now it came to pass that Alma said unto him: Behold, I am grieved because of [Page xxix]the hardness of your heart, yea, that ye will still resist the spirit of the truth, that thy soul may be destroyed. (Alma 30:37–46)

And the same mixture of preaching, testimony, and reasoning has been enjoined upon members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in this modern dispensation as well. “Behold,” the Lord told William E. McLellin in a revelation given through the Prophet Joseph Smith on 25 October 1831, at Orange, Ohio,

verily I say unto you, that it is my will that you should proclaim my gospel from land to land, and from city to city, yea, in those regions round about where it has not been proclaimed. . . . Go unto the eastern lands, bear testimony in every place, unto every people and in their synagogues, reasoning with the people. (Doctrine and Covenants 66:5, 7)

McLellin was to proclaim the gospel, yes, and to bear testimony, but he was also to reason with his audience—which sounds very much like a description of a type of apologetic argumentation. Indeed, it is difficult to conceive of a method of testifying that in no way includes the faculty of reason. Even to say something as simple as “I have felt divine love, so I’m confident that there is a God who loves me” represents an elementary form of logical argument. Likewise, according to a revelation given at Hiram, Ohio, in November 1831, “My servant, Orson Hyde, was called by his ordination to proclaim the everlasting gospel, by the Spirit of the living God, from people to people, and from land to land, in the congregations of the wicked, in their synagogues, reasoning with and expounding all scriptures unto them” (Doctrine and Covenants 68:1).

Leman Copley, too, called along with Sidney Rigdon and Parley P. Pratt on a mission to his former associates among the [Page xxx]Shakers by a revelation given at Kirtland, Ohio, in March 1831, was told to “reason with them, not according to that which he has received of them, but according to that which shall be taught him by you my servants; and by so doing I will bless him, otherwise he shall not prosper” (Doctrine and Covenants 49:4).

On 1 December 1831, in the wake of a series of newspaper articles written by an apostate named Ezra Booth, the Lord told the members of His little church:

Wherefore, confound your enemies; call upon them to meet you both in public and in private; and inasmuch as ye are faithful their shame shall be made manifest. Wherefore, let them bring forth their strong reasons against the Lord. Verily, thus saith the Lord unto you—there is no weapon that is formed against you shall prosper; and if any man lift his voice against you he shall be confounded in mine own due time. (Doctrine and Covenants 71:7–10)31

Not surprisingly, the Church’s contemporary missionary program, too, encourages and trains its representatives to give reasons, as the missionaries have always been expected to do. Preach My Gospel, the contemporary guide to missionary service, lists scriptural passages by the scores at appropriate places in its lessons for investigators.14 Missionaries are plainly intended to use these to reason with those they are teaching, to explain the claims of the Restoration and to support and ground them in revealed scripture.

This is what we humans normally do in conversation. When someone asks why we’re voting for Barack Obama or supporting Mitt Romney, or why we think the Dodgers the [Page xxxi]best team in baseball, we typically give reasons. Simply replying “Because!” seems, somehow, lacking.

Paul J. Griffiths, a trained scholar of Buddhist studies whom I’ve quoted previously, published a book in 1991, entitled An Apology for Apologetics, in which he “defend[s] the need for the traditional discipline of apologetics as one important component of interreligious dialogue.”32 He does so against what he calls a scholarly orthodoxy that “suggests that understanding is the only legitimate goal; that judgement and criticism of religious beliefs or practices other than those of one’s own community is always inappropriate; and that an active defense of the truth of those beliefs and practices to which one’s community appears committed is always to be shunned.”33 In his strongly expressed opinion, “such an orthodoxy (which tends to include the view that the very idea of orthodoxy has no sense) produces a discourse that is pallid, platitudinous, and degutted. Its products are intellectual pacifiers for the immature: pleasant to suck on but not very nourishing.”34

Professor Griffiths argues for what he calls the principle of the “necessity of interreligious apologetics.”35 This is how he formulates it:

If representative intellectuals belonging to some specific religious community come to judge at a particular time that some or all of their own doctrine-expressing sentences are incompatible with some alien religious claim(s), then they should feel obliged to engage in both positive and negative apologetics vis-à-vis these alien religious claim(s) and their promulgators.36

[Page xxxii]Professor Griffiths distinguishes negative apologetics from positive apologetics in precisely the same way that I have. As an example of negative apologetics, which he describes as a defense of a proposition or belief against criticism, he points out that a critic of Buddhism might argue that the two propositions There are no enduring spiritual substances and Each human person is reborn multiple times are mutually contradictory. In response, a negative Buddhist apologetic will seek to show that there is no contradiction between them.

Critics of Christianity often argue that the existence of massive natural evil in the world is incompatible with the existence of a benevolent God. A negative Christian apologetic will argue that the fact of natural evil actually can be reconciled with belief in a loving God.

In a Latter-day Saint context, negative apologetics will seek to rebut, to neutralize, claims such as Oliver Cowdery denied his testimony or Joseph Smith’s introduction of polygamy shows him to be a man of poor character or Mormonism is racist. Attacks against the claims of the Restoration began even before the publication of the Book of Mormon and the organization of the Church, and Latter-day Saints have been responding to them for nearly two centuries now. Regardless of whether the responses are have been sophisticated or not, or are judged adequate or inadequate, they constitute negative apologetics.

Positive apologetics seek to demonstrate that a given religious or ideological community’s practices or beliefs are good, believable, true, and/or, in some cases, superior to those of some other community. While negative apologetics is defensive, positive apologetics is offensive—by which, incidentally, despite my richly deserved reputation for vicious and unethical polemics, I don’t mean to say that it necessarily gives offense.

[Page xxxiii]Griffiths argues that religious communities have an epistemic or even ethical duty to engage in apologetics.37 Why? Because, since religious groups typically claim that their teachings are true, they are obliged to respond when, as usually happens, somebody else claims that, in fact, their teachings are wholly or partially false. We should not be indifferent to the truth or falsity of what we claim, and all the more so when our claim involves matters of ultimate importance. This means that religious communities have a duty to engage in negative apologetics, to defend or justify their assertions.

Mainstream Buddhists, for example, who espouse what has been called the doctrine of “No Self,” believe that the notion of a continuing substantial “soul,” such as most Christians affirm, creates and perpetuates suffering. If challenged by Buddhist thinkers on the question, it is the duty of the Christian community to justify its affirmation or to withdraw it.38

In fact, knowing of the existence of competing doctrines that contradict its own teachings, representatives of a religious community might proceed to a positive apologetics, seeking to demonstrate that one or more of their claims are, in fact, very believable, or even, perhaps, superior to rival views. There is, in fact, arguably an ethical imperative to do so, because religions commonly hold that adherence to their doctrines is important, and maybe even essential, to salvation. Just as a person on the shore holding a life rope has an obligation to help a drowning man, so do those who have the saving doctrines or practices have an obligation to help those who might otherwise perish.

[Page xxxiv]Griffiths also argues that apologetics can substantially benefit the faithful, because of what he describes as

the tendency of members of religious communities not to think in any very self-conscious way about the implications of the views into which they have been acculturated. These views are part of their blood and bone, among the presuppositions of their existence as human beings.39

Religious communities are, he says, typically forced into more nuanced understandings of their own doctrines and practices “primarily by pressures from outside or by criticisms from dissident groups within.” He cites as an example the creedal formulae generated by the ancient ecumenical councils of the Christian church.40 A Latter-day Saint might cite the impetus given to Mormon historians by Fawn Brodie’s assertion that the Joseph Smith’s First Vision was a fiction invented relatively late in the Prophet’s life. Several earlier accounts of the Vision were discovered as part of an effort to counter her claim. Apologetics, says Griffiths, who is a scholar of Buddhism, “is a learning tool of unparalleled power. It makes possible a level of understanding of one’s own doctrine-expressing sentences and their logic, as well as those of others, which is not to be had in any other way.”41

Moreover, Griffiths argues, a failure to take contradiction between competing truth claims seriously, a kind of “can’t we all just get along” indifference to resolving disputes, will have very serious consequences. “The result,” he says, “would be both relativism and fideism: religious communities would become closed, impermeable, incommensurable forms of life.”42

With Paul Griffiths, I’m convinced that apologetics is an important part of scholarly discourse in religious studies, that [Page xxxv]it should be considered a kind of religious studies, and, therefore, of Mormon studies.

Accordingly, I’m delighted to announce the launch of a new venture in Mormon studies, Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture—the product of a team that came together only a few days back, after my return from overseas less than two weeks ago. Its first article is now online.

It will not be purely an apologetic journal, but it won’t exclude or disdain apologetics, either.

Published online, it will be available in various ways, including print on demand, and will represent something far more sophisticated, technologically speaking, than we have yet seen in the field of Mormon studies. Being primarily published online, it will also be free to post articles, reviews, and notes as they’re ready to be made public. At a certain point, we’ll close the issue and commence a new one.

This will, I think, be an exciting venue for faithful Latter-day Saint thought and scholarship, as well as for readers. It will require some stretching, perhaps, but we intend to keep firmly in mind not merely the scholarly elite but the Relief Society sister in Parowan and the ordinary Mormon in Ogden.

Welcome to Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, the peer-reviewed journal of The Interpreter Foundation, a nonprofit, independent, educational organization focused on the scriptures of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Non-print versions of our journal are available free of charge, with our goal to increase understanding of scripture. Our latest papers can be found below.

Welcome to Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, the peer-reviewed journal of The Interpreter Foundation, a nonprofit, independent, educational organization focused on the scriptures of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Non-print versions of our journal are available free of charge, with our goal to increase understanding of scripture. Our latest papers can be found below.

Conference Proceedings are now available

Conference Proceedings are now available