[Page 153]Abstract: John S. Thompson explores scholarly discussions about the relationship of the Egyptian tree goddess to sacred trees in the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and the temple. He describes related iconography and its symbolism in the Egyptian literature in great detail. He highlights parallels with Jewish, Christian, and Latter-day Saint teachings, suggesting that, as in Egyptian culture, symbolic encounters with two trees of life — one in the courtyard and one in the temple itself — are part of Israelite temple theology and may shed light on the difference between Lehi’s vision of the path of initial contact with Tree of Life and the description of the path in 2 Nephi 31 where the promise of eternal life is made sure.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See John S. Thompson, “The Lady at the Horizon: Egyptian Tree Goddess Iconography and Sacred Trees in Israelite Scripture and Temple Theology,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 217–42. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/ancient-temple-worship/.]

[Page 154]In the last few decades, a flurry of scholarly debate pertaining to manifestations of female sacred tree motifs in the iconography and extra-biblical texts of ancient Israel and surrounding nations has raised many questions concerning how one should understand Israelite religion and Biblical passages such as Deuteronomy 16:21, 2 Kings 23:4-7, Proverbs 3:18, and Isaiah 17:8 among many others.1 Daniel Peterson extended this debate to the Book of Mormon by pointing out the record’s claim that Lehi and Nephi, father and son living in the Jerusalem culture of the late 7th century bce, both saw visions of a divine tree whose fruit was white and “desirable to make one happy,” and then Nephi, in response to know the meaning of the tree, saw a vision of a virgin who later held a child in her arms (1 Nephi 8:10-11; 11:8-20).2 Nephi describes the appearance of both the tree and the virgin using the same terminology (both are “exceedingly” “fair,” or “beautiful,” and “white”),3 leaving the reader with the impression that the two are somehow related. Margaret Barker noted that the details in and surrounding the tree visions of Lehi and Nephi fit comfortably within the context of late seventh century bce.4

Much of the debate has focused on the extent to which these connections between sacred trees and women reflect the actual theology and worship of ancient Israelite religion. While the biblical text appears to condemn the Israelites for worshipping any deity besides the god of Abraham, including female deities connected to tree-related iconography, both the Bible and the Book of Mormon depict sacred trees as female in a positive light as well.

These positive views of female sacred trees in scripture and extra-biblical texts as well as what appear to be tree goddess figures in the archeological record of Israel has caused some scholars, such as William Dever, to postulate that the Israelite religion had at one time, in its earlier periods, some polytheistic understandings, including a divine female, who continued in the later periods among the less centrally controlled “folk” religions of ancient Israel.5 Barker reasons that these earlier, pre-exilic understandings of both male and female “hosts of heaven” were central to Israelite temple theology but appear to have been excised from or suppressed in the later centralized religion in Jerusalem through such movements as the Deuteronomist school and Josiah’s reforms.6 Scholars such as these are providing intriguing and well-developed reasons for the fragmentary persistence of female divine trees and goddess figurines in the texts and artifacts of ancient Israel, even though the later central religion and its official records appear to have developed polemics against such.

[Page 155]In contrast, Jeffrey Tigay’s monograph that surveys proper names in Hebrew inscriptions calls for caution among scholars who assume the Israelites had earlier practiced full-blown polytheistic worship, for the evidence shows that few of the theophoric names of the ancient Israelites mention other gods.7 Steven Wiggins effectively argues for the difficulties of drawing any real conclusions concerning Israelite worship, whether strictly monotheistic or polytheistic, based on the current evidence.8 The debate concerning the nature of Israelite religious history will likely continue for some time, and whether the ancient Israelites worshipped or at least acknowledged female deities in pre-exilic periods will be central to truly understanding their religious history and theology as well as the Christianity that grew out of it.

Because of the tree-centric nature of the divine feminine in the texts and images of the Israelite sources, most of the comparative studies have collected images and focused upon the simple fact that other cultures of the ancient Near East had goddesses appearing in connection with divine trees as well. This study will attempt to go a step further and explore the iconographic specifics surrounding these images, especially in Egypt, during the time-period of Israel’s kingdom and discuss any insights these specifics may provide concerning the use of female sacred trees in Israelite texts and temple theology.

Egyptian cultural influence in Israel was at one of its high points during the late seventh century bce, a highly relevant era, scholars believe, for the formation of many Old Testament books.9 The Book of Mormon claims its origins in Jerusalem during that time-period as well and mentions some of this Egyptian influence.10 Additionally, recent research is demonstrating that the Old Testament temple tradition has much more in common with the Egyptian temple tradition scholars have assumed, even from a very early date.11 Consequently, a comparative approach between these two cultures may be fruitful. Of course good scholarship requires that iconographic specifics be analyzed and understood within the context of their own culture to correctly ascertain their meaning within that culture and cautions against “over-reaching” conclusions (e.g., assuming that parallel symbols in two different cultures have parallel meaning or assuming the direct influence of one culture on the other); however, swinging the pendulum too far the other way and ignoring the broader cultural milieu in which a society existed may limit one’s ability to fully understand the texts or images that society produced.

A careful analysis of the iconographic specifics related to female divine trees in ancient Egyptian scenes illuminates the following details:

- [Page 156]They appear mostly in places of transition, such as at the western and eastern horizons or at courtyard entrances to temples and tombs;

- They frequently appear as sources of water for drinking, in addition to sources of fruit for eating;

- They often appear with labels designating them as mothers and may even appear nursing a child; and

- They can also appear in connection with concepts of cleansing or purifying.

These same four details appear in Israelite sources concerning sacred trees as well, providing additional facets to consider when seeking to understand the meaning of female sacred trees in Israelite texts and temple theology. Particularly, the comparative material suggests that the divine trees in the Israelite sources may have more than one meaning and appear in more than one location in the temple or cosmic landscape.

Four Specifics in the Iconography of Egyptian Tree Goddesses

From the early Old Kingdom, Egyptian female deities were associated with trees. In the Old Kingdom cult centers at Memphis and at Kom el-Hisn, Hathor was referred to as the nb.t nh.t rs.t “lady of the southern sycamore,” a type of fig tree,12 and nb.t jmAw “lady of the Date Palms;” and Saosis, the wife of Atum in some myths, was closely related to the acacia tree.13 Male gods also appear next to or under trees from the earliest texts,14 but Buhl points out that although “there may have been reliefs or statues of [male] deities with their sacred animals in the shelter of a sacred tree serving as a place of worship for the Egyptians, such gods were not regarded as tree deities.”15

Associations of sacred trees with female deities also appear in the New Kingdom and later — the time period in which the nation of Israel was formed and existed. During this period, artists depicted Egyptian female deities either merged with a tree in some way, superimposed on a tree, emerging from a tree’s branches, standing beside a tree, or having a tree-related headdress or other iconography.16 The following analyzes the four details that occur frequently in those scenes related to the tree goddesses in Egypt:

1. Egyptian Tree Goddesses Appear Mostly at Places of Transition

In the texts and iconography, Egyptian tree goddesses most often appear in relation to both the western and eastern horizons, where the sun sets [Page 157]and then rises respectively. They also appear in relation to the entrances of temples or tombs. This is not surprising since ancient Egyptian temples and tombs have a close association with the horizon.17 Indeed, the Great Pyramid’s ancient name is Khufu’s Horizon.

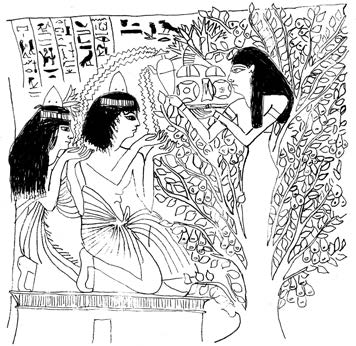

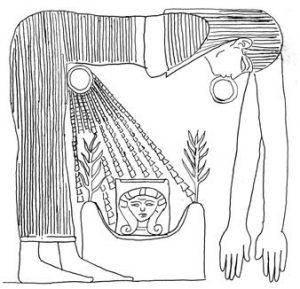

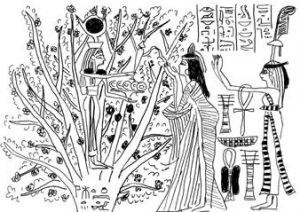

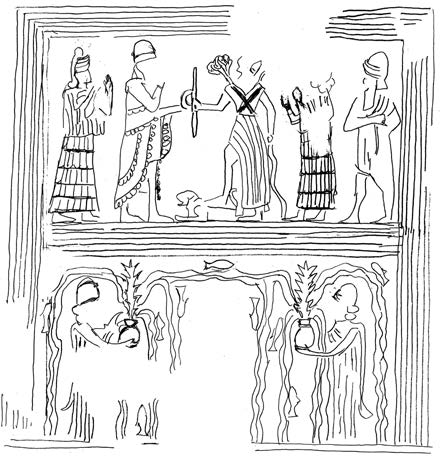

In Egyptian theology, one first encounters a tree goddess in the western horizon, at the beginning of the afterlife journey.18 One of the more common scenes of tree goddesses on the Theban tomb-walls of the New Kingdom era is an illustration of Book of the Dead 59, a text that typically occurs near the beginning or first hour of the netherworld journey. Such a scene appears in the tomb of Sennedjem, where he and his wife meet a tree goddess pouring a libation Figure 1.19

Figure 1: Sennedjem and his wife meet a tree goddess

pouring a libation in front of a tomb entrance

That such a meeting occurs near the beginning of the netherworld journey can be seen in the art, for the tree goddess seems to appear outside, near the entrance of the temple tomb that is below the couple and into which they will journey.

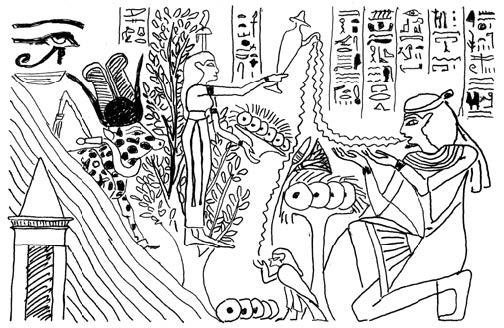

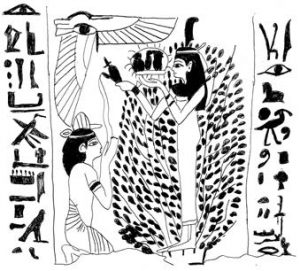

Figure 2 appears to personify the west as a tree goddess (denoted by the hieroglyph for the west above her head) pouring water at the horizon mountain from which Hathor, as a cow, emerges to greet him. All of this takes place in front of what appears to be a tomb chapel entrance depicted in the lower left.20

Figure 2: A tree goddess pouring water at the horizon mountain from

which Hathor, as a cow, emerges to greet him

Sometimes artists will depict the tree coming out of an object that looks like the standard hieroglyph for a horizon mountain (see Figure 3, Figure 6, and Figure 9).21

[Page 158]

Figure 3: Hathor as tree-goddess in an object shaped as the

hieroglyph for mountain, suggesting the horizon

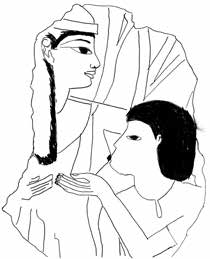

Figure 4: The initiate embraced by the goddess of the west at the horizon mountain, in front of tomb chapel entrance

Figure 4, from the tomb of Amenemope, has the tree goddess pouring water while growing from the waters of a pool.22 Nearby, the initiate is embraced by the goddess of the west at the horizon mountain and in front of the tomb chapel entrance.

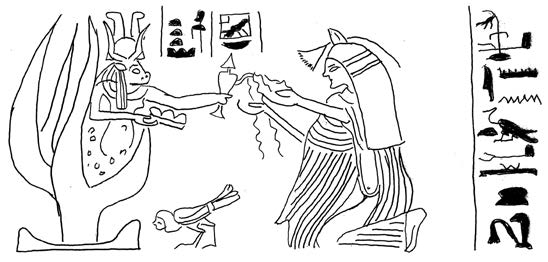

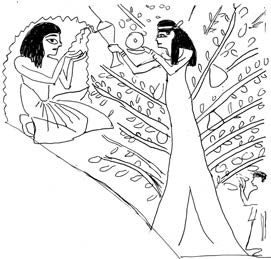

On a pillar in the middle of a chamber belonging to Thutmose III, surrounded by the twelve hours of the underworld journey depicted on the walls, a tree nurses a child (Figure 5).23 That the king is portrayed as a young child and the tree is placed in the center of the room may suggest that this scene was understood as representing the beginning of the netherworld journey prior to passing through the twelve hours of the night in the surrounding depictions.

Figure 5: Thutmose III nursed by his mother, Isis as tree-goddess

The Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts of Pepy I may prefigure these scenes. When the deceased king comes to his mother-goddess in the [Page 159]netherworld journey, she says to her son “accept my breast and suck from it … that you may live.” “Though you are small … you shall go forth to the sky as falcons. …” The text continues, “This Pepi will go to the sky … to the high mounds and to yonder high sycamore in the east of the sky, the bustling one atop which the gods sits.”24 This text indicates that the movement for the deceased, newly born in the netherworld, is to leave from nursing upon his mother in the west (i.e., the western tree goddesses) and journey to the eastern sycamore. The gods, as well as the deceased in other sources, sit in the top of this eastern tree like birds.25 Book of the Dead 64 has the deceased exclaiming about this eastern sycamore, “I have embraced the sycamore and the sycamore has protected me.”

Figure 6: Hathor’s face at the mountain

of the eastern horizon, with the newly

born sun’s rays shining down

Figure 6, from the Temple of Dendera, depicts Hathor’s face between the mountains of a horizon glyph. Tree motifs appear in connection with the mountains and the newly born sun’s rays shining down, suggesting this is the eastern horizon.26

2. Sacred Trees as Sources of Water

A frequent detail occurring in the female divine tree scenes is the pouring out of liquid for the recipient(s) who approaches the tree. Again, Figure 1 appears in the nineteenth dynasty tomb of Sennedjem in Deir el-Medineh, originally a vignette for Book of the Dead 59, and portrays the goddess Nut, with her lower torso merging with a [Page 160]tree trunk, not only presenting a tray of fruit and other goods but also pouring water from a hes-jar into the hands of the deceased.

Figure 7: Ma’at as tree goddess pours

water into the hands of the deceased for

drinking

That the water is for drinking and not merely caught in the hand is made clear from images such as Figure 7 where the tree goddess, in this case Ma’at, offers a tray of goods and pours water into the hand of the recipient which is held up to the mouth.27 Figure 2 clearly has the water flowing across the hands and into the mouth of the recipient.28

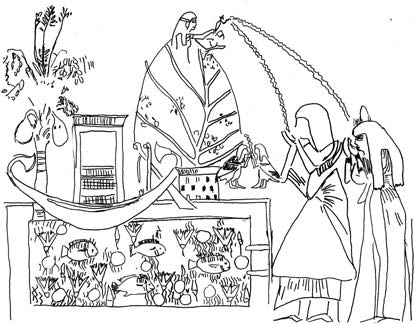

In addition to flowing vases, tree goddesses are often depicted in relation to pools of water as seen in Figure 8 wherein the goddess emerges from a tree pouring water that grows near a pool complete with fishes, lotus plants, and a boat shrine.29 Figure 9 and others demonstrate that not only the tree goddess’ vase but also the closely associated pools of water can be sources for drinking.30

[Page 161]

Figure 8: A tree goddess pours water as she

emerges from a tree growing near a pool

Figure 9: Both the vase of the tree goddess and the

associated pools of water as sources for drinking

Figure 10: Mesopotamian cylinder seal depicting a flowing vase and

plants emerging from the body of the goddess

Tree goddesses with flowing vessels are also attested in other Near Eastern art such as this seal impression from Mesopotamia of an earlier period (Figure 10).31 Not only does the scene depict branches emerging from the goddess’ body, but traces of a plant emerging from the vessel are preserved as well.

3. Sacred Trees as Mothers

Figure 11: Nut, described as the mother

of the gods, offers figs and water

In Figure 11, Nut is shown standing in the midst of a tree, offering a tray of figs and water from a hes-jar and is described as the one who gave birth to or is “the mother of the great gods.”32 Labels declaring [Page 162]the motherhood of these tree goddesses are common.

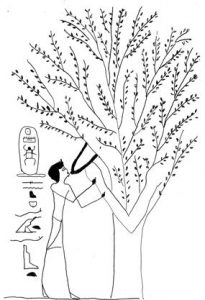

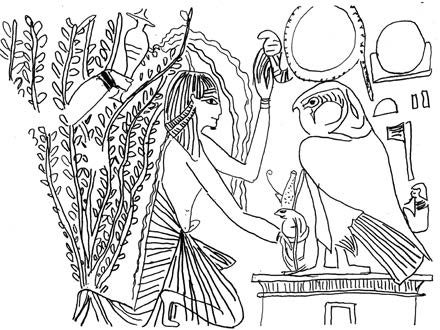

Figure 12: A female nursing a child

among tree branches

Figure 5, mentioned earlier, depicts the king suckling at the breast of an anthropomorphized tree, the text indicates that the tree is “his mother, Isis.” A fragmentary image depicting a female nursing among tree branches may relate (Figure 12).33

4. Sacred Trees That Cleanse or Purify

Figure 13: Streams of water are not

only for drinking, but fall in front of

and behind the individual, suggesting

purification

Some scenes from Egypt portray the goddess not only pouring a libation of water for drinking, but the streams also appear to fall in front of and behind the individual as in Figure 13 from the tomb of Pashedu in the Valley of the Kings.34

Figure 14 portrays the streams poured over the top of the head from behind which, in the Egyptian canons of iconography, is a representation of purification.35

That the goddesses are typically shown pouring water from a hes-jar in all the examples is also significant for such jars are typically used for ritual purification throughout Egyptian history.

Figure 14: Streams poured over the top of the head of the individual,

suggesting his purification

A common placement of the scenes of tree goddesses in the New Kingdom tombs is next to offering tables. For example, in the Tomb of Nakht, the goddess, [Page 163]with a sycamore emblem on her head, appears twice, flanking both sides of an offering table.36 In later periods, the goddess appears directly on offering tables with libation areas and Book of the Dead 59 carved thereon as well.37 Libation is the first rite of the royal and non-royal offering lists from the earliest of times and is made for the purpose of purifying the deceased.

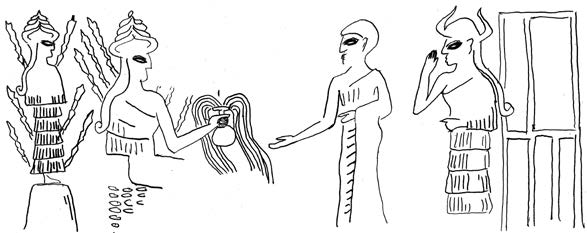

Likewise, in Mesopotamia, Figure 15 from Mari portrays goddesses with vases from which plants and flowing water emerge in a preparatory purification area below where the recipient, who is shown in the above, more sacred, chamber, was first cleansed.38

Figure 15: Investiture Panel from Mari portraying goddesses in a

purification area holding vases with flowing water and plants

The Four Specifics in the Israelite Sources

1. Sacred Trees as Sources of Water

Like the Egyptian tree goddesses, divine trees in Israelite sources are also closely associated with sources of water. Genesis 2:8-9 indicates a tree of life came “out of the ground … in the midst of the garden” but then immediately indicates that a river also “went out of Eden to water the garden.” The text indicates that the river parted “from thence” (i.e., from the garden) into four heads, likely a representation of the waters flowing into the cardinal directions.

It is unclear from the sources whether the river should be understood as flowing out of the garden in a single stream before it parts into four heads or parting near its source within the garden and then flowing out in multiple streams. The garden of Eden imagery of Ezekiel 47 seems to [Page 164]have a single river flowing east out of the temple; however, the garden of Eden imagery in chapter 31 has a deep spring coming up into rivers (plural) around the mighty tree and flowing out in multiple streams to the other “trees of Eden, that were in the garden” (Ezekiel 31:3-9). Ben Sira also speaks of streams flowing within the garden. Genesis Rabbah XV indicates that the waters “branched out in streams under the tree of life,” suggesting many rivers within the garden as well.

If the river of Genesis 2 parts into the four cardinal directions prior to leaving the garden, then the garden would be understood as the high place since the water flows downhill in each direction. Further, if the water parts and leaves the garden in the cardinal directions, then the declaration that the river first went “out of Eden to water the garden” must be understood as a spring or fountain. Ezekiel 31:4, 47:1, and Revelation 22:1 certainly portray it as such, coming up as a spring from the deep, from under the threshold of the temple, or from beneath the throne and tree.

While both a tree and fountain/river exist in the garden of Eden of Genesis, the relationship between the two, while explicit in the Egyptian images, is not readily apparent in the Genesis account. Other Israelite sources do specify some relationship between these two. In Ezekiel 31, the fountain or spring from the deep causes the great tree to grow [Page 165]mightier than all the other “trees of Eden, that were in the garden of God.” Genesis Rabbah XV 6 mentions that the waters branched out “under” the tree. Likewise, the tree in Revelation 22 can be understood as having its roots in and around the river.

Closer to the Egyptian examples, which combine the tree and flowing water in the image of the goddess, the text in Ben Sira has the tree speaking as if she is both a source of fruit and water: “Come to me … and eat your fill of my fruit, those who eat of me will hunger for more, and those who drink me will thirst for more.” Likewise, the Book of Mormon tracks closer to the Egyptian examples and blurs the distinction between tree and fountain. Nephi indicates that the rod of iron led to the “fountain of living waters,” and then immediately adds “or to the tree of life,” both, he explains, represent the same thing, even God’s love (1 Nephi 11:25).39 Alma’s tree of life grows up from a seed “planted in the heart” (Alma 32:28) and appears to be a fountain also. It not only satisfies hunger, but it quenches thirst: “and ye shall feast upon this fruit even until ye are filled, that ye hunger not, neither shall ye thirst” (Alma 32:42).

The Egyptian examples explicitly show those who approach the tree goddess are drinking the water she pours out. The biblical examples do not appear to focus on one approaching a divine tree to drink. However, both the aforementioned examples, i.e., Ben Sira and Alma 32 in the Book of Mormon, explicitly mention drinking as a purpose for coming to the tree. Additionally, Alma 5:34 has God saying: “Come unto me and ye shall partake of the fruit of the tree of life; yea, ye shall eat and drink of the bread and the waters of life freely.”

2. Sacred Trees As Mothers

Much of the tree goddess examples attested in the ancient Near East emphasizes their sexual nature as consorts to male deities; however, the Egyptian examples emphasize their roles as mothers, rather than sexual consorts. The only Old Testament reference that directly equates trees with motherhood is in Ezekiel 19:10-11 wherein the “mother,” as a vine, is “planted by the waters” and is “fruitful.” Her rods are described as “strong” and are “for scepters of them that bear rule.” The early Christian reflection of this idea in Revelation 12 speaks of the lady, clothed in the sun, who is a mother giving birth to a royal child who rules with a rod of iron.40

Interestingly, the vision of Nephi in the Book of Mormon not only equates the tree of life to a virgin mother who gives birth to a child, but [Page 166]upon closer reading, the child of Nephi’s vision, like the child in Ezekiel 19 and Revelation 12, appears as a king ruling with a rod of iron. When Nephi desires to know the meaning of the tree that his father Lehi saw, he was shown a vision of a virgin who is described as the “mother of the son of god … bearing a child in her arms” (1 Nephi 11:18-20). This vision immediately gives way to another vision of this “Son of God going forth among the children of men; and I saw many fall down at this feet and worship him” (1 Nephi 11:24). That people fall down and worship at the Son of God’s feet suggests royalty, causing Nephi to exclaim “I beheld that the rod of iron, which my father had seen, was the word of God, which led to the fountain of living waters, or to the tree of life” (1 Nephi 11:25). Nephi’s child is the son of both God and of the virgin tree, and the rod of iron is the son’s scepter.

Elsewhere in the Book of Mormon, Nephi’s brother, Jacob, quotes an ancient prophecy by a figure named Zenos, who refers to a great central olive tree in a vineyard as the “mother tree” (Jacob 5:54-60). Other trees are formed from her branches, and the resulting branches of the other trees are eventually grafted back into the mother tree.

3. Sacred Trees at Places of Transition

One encounters the Egyptian tree goddess who pours water at the western horizon — near the entrance to the netherworld — prior to an ascent to the tree goddess in the eastern horizon. Likewise tree and water motifs appear in connection with Israelite sacrificial altars and courtyards, outside the entrance of temples, prior to one entering or ascending to the full tree of life in the Holy of Holies or in the heavenly city (Revelation 22:2).

Abraham builds an altar (a built altar suggests a sacrificial altar) at the oak of Moreh where God had appeared unto him in Genesis 12:6 and later plants a tamarisk tree in Beer-sheba where he calls upon the name of God in Genesis 21:33. Deuteronomy explicitly forbids an asherah, a tree-like motif, from being erected near the altar (Deut. 16:21-22), indicating that some are want to put one there. Joshua set up a covenant stela under a tree near the temple (Joshua 24:26). Psalms 92:12-14 (cf. 52:8) likens the righteous to trees planted and flourishing in the courts of the temple. These examples suggest the possibility that tree motifs were erected in the Israelite temple courtyards in connection with the altar and before the door of the temple. Indeed, Ezekiel’s fountain of water comes up not [Page 167]in the Holy of Holies but from beneath the threshold of the temple’s door and flows to the trees of life outside the temple (Ezekiel 47:1, 7, 12).

A combination tree and water motif is built into the courtyard design of Solomon’s temple. The brazen sea was not just a large bowl of water, but a bowl with gourd-shaped knobs all around and shaped like a lily blossom (1 Kings 7:23-26). Further, the pillars on the porch, flanking the door of the temple, had capitals that were also lily-shaped, with pomegranates hanging from them (1 Kings 7:18-22). Could these objects represent some sort of initial interaction with a divine tree motif preparatory for entering the temple, in likeness of the western tree goddess in Egyptian culture? Indeed, Book of the Dead 59, the text that most often accompanies the western tree goddess vignettes, alludes to the Hermopolitian myth concerning the birth of the sun. Versions of this myth portray the sun rising from a lotus blossom that itself was the first to rise out of the primordial waters, again connecting waters of new birth, a beginning, with a tree motif.

The tree/fountain of life in Lehi and Nephi’s visions, at first glance, appears to be at the end of a journey, at the end of the path. However, the fact that some of the numberless people from the field representing “a world” (1 Nephi 8:20-21) arrive at the tree, partake, and then leave due to the mocking of those in the great and spacious building suggests that not all trees of life are at the full end of one’s eternal journey. Likewise, one can partake but then forsake the “the fountain of Wisdom” in the Book of Baruch 3.10-13. These examples suggest an initial interaction with a tree of life that likely represents or foreshadows, but is actually different from, the tree of life at the full end of one’s journey.

4. Sacred Trees Relative to Cleansing or Purification

Not only do the waters of the Egyptian tree goddesses give life and refreshment to the netherworld traveler, but they also appear to purify as the streams fall around the individual. Likewise, the Israelite priests washed in the water of the lily-shaped laver near the tree-shaped pillars in the temple courtyard prior to their service within (see Exodus 30:19-21; 40:30-32).

An Abrahamic narrative outlines a custom that may echo the ritual act of washing at the door of the temple. Not only does Abraham call upon and encounter God in relation to trees as noted above, in Genesis 18 Abraham, dwelling among the oaks of Mamre and sitting in the doorway of his tent, welcomes three holy men by stating, “Let a little water, I pray you, be fetched, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves [Page 168]under the tree” (Genesis 18:4). While this can be understood simply as an act of desert community hospitality, the act of washing and resting under a tree at the door of a house as part of a journey certainly reflects the ritual material as well.41

That initial rituals, prior to entering temples, can be associated with divine trees/fountains is more clearly seen in the Gnostic Trimorphic Protennoia that declares baptism occurs in the fountain of living waters: “the baptizers … immersed him in the spring of the water of life.”42 Indeed, Alma connects partaking of the tree of life with baptism explicitly: “ … unto those who do not belong to the church I speak by way of invitation, saying: Come and be baptized unto repentance, that ye also may be partakers of the fruit of the tree of life” (Alma 5:62). It is difficult here to ascertain if Alma is saying that baptism precedes partaking of the tree of life or that baptism is the equivalent to partaking of the tree of life. In light of the broader cultural parallels, the latter is a strong possibility.

Conclusions

The Egyptians viewed their ascent into heaven as a journey or progression that begins at the western horizon. This horizon corresponds with mortal death (the setting of the sun) but was also viewed as a birth into a new life in the hereafter — the horizon was a place of transition. At this initial transition point, the deceased encounters the Lady of the West. Because the deceased is being reborn into a new life, the goddess, depicted as a tree pouring water and growing near garden pools, is labeled as a mother figure and even nurses her child.43 Since the sun and the world, as the ancient Egyptians portrayed it, came out of the primordial waters of Nun, just as a baby comes from a watery womb, the mother-goddess is closely associated with waters of life.

As a baby who comes forth from the waters of the womb is considered pure, so the deceased is pure when born into the hereafter as symbolized in the streams of water the tree goddess pours that surround the individual. The deceased also drinks from the water she pours or from the milk of her breast in order to live and have power to make the coming journey as PT 470 and BD 59 state.

A netherworld birth, nourishing/nursing, and purity would explain the appearance of a woman as a mother who nurses or pours water and purifies at horizon-mountains or at entrances to tombs. Her equation to trees and fountains may be natural in the context of a desert community where the very symbols of life are the oasis of trees that indicate [Page 169]life-giving water and shade from the heat of day. However, this initial birth is not the final destination. There is an ascension, “as falcons,” to the eastern horizon where the “high sycamore” tree goddess is met and embraced, suggesting another transition or birth, even a resurrection, where the deceased is illuminated as the dawning rays and can rise with the sun-god, Re.

The symbolism of this journey or ascension into the sky becomes intertwined with the main offering ritual sequence of the temples and tombs in ancient Egypt, forming their temple theology. The western tree goddesses, in the New Kingdom tombs and later, appear in connection with the tomb chapel offering tables having libation vessels and food depicted thereon and thus relate her to the sequence of rites performed therein. The initial part of this sequence includes a libation of water, an opening of the mouth, eyes, ears, and nose by means of a natron-washing, followed by a small meal offering. Indeed, the ancient Egyptians viewed these initial rituals as a birth, so the presence of a mother figure would be expected.44

In the Israelite temple theology, there appears to be a similar pattern. The sources above indicate that the courtyard of the temple may be one location that a divine tree motif in ancient Israel once appeared. Trees seem to appear in connection with sacrificial altars in the Abraham material, in Deuteronomy, and other Old Testament sources, just as they appear in connection with offering tables in the Egyptian theology.

Being in the courtyard of the Israelite temple, the tree motif would be closely associated with the waters of the laver that appeared there as well, a place where priests were purified prior to their ascension into the temple, just as the tree goddesses in Egypt poured water and purified the deceased prior to entering the horizon or tomb. Indeed, the laver in the courtyard of Solomon’s temple had plant-like décor tying the two symbols of water and vegetation together as in the Egyptian material.

The courtyard tree motif stands in contrast to the tree or trees inside the temple.45 Similar to the Egyptian worldview, the Israelite temple has a tree near the beginning as well as near the end of the spiritual progression. Judging by the greater Near Eastern background, a tree/fountain motif indicates a place or time of transition as part of the general ascent. Consequently, a tree/fountain motif in the courtyard as well as inside the Israelite temple might represent differing levels of ascent or transition. The trees are feminine in both the Israelite and greater Near Eastern tradition because they are viewed as mothers that facilitate these [Page 170]transitions from a lower to a higher order, as a birth from one life to another as one ascends to God.

The Early Christian church certainly seems to view the courtyard as a place of rebirth. Matthew’s Jesus interprets the two messengers in Malachi 3:1 as John the Baptist and himself (Matthew 11:10; cf. Matthew 3:1-11). John is the Aaronic messenger in the courtyard, who prepares the way, while Jesus is the Melchizedek priest and messenger of the covenant who will “come to his temple.” John prepared the way to the temple by teaching repentance and baptism, a ritual that Jesus declares is one of being “born of water” (John 3:5). In contrast, Jesus administers the blessings of the covenant inside the temple, which John declared would include an additional baptism of the Holy Ghost, which Jesus also called being “born of … the spirit” (John 1:33; cf. John 3:5). Like the Egyptian theology of at least two births, one of water in the western horizon and the other in the east with the blaze of the sunrise, the Christian temple theology also promises at least two births — one in the courtyard of water and the other of fire in the temple. Such an understanding may provide reasons for finding cultic reflections of a mother tree of water in the courtyard followed by a mother tree of oil in the temple.

Although Israelite culture and texts recognized that the cultural trees of life and fountains of water were women. Jesus does declare that he is the ultimate tree and fountain, and that we, by association, are to be children born of him. For example, Jesus declares in John 15:1-2 that he is the true vine and we are to be his fruit-bearing branches. Likewise, Nephi speaks of Jesus as the “true vine” and “olive tree” just before discussing with his brothers the meaning of the tree of life in 1 Nephi 15:15-21. In John 4:7-26, Jesus says “Give me to drink” when approached by a woman at the well of Jacob in Samaria. She is the life-giver, the pourer of water, in this opening moment of the narrative. However, as the dialogue progresses, Jesus reverses the roles and places himself as the water-giver. “If thou knew the gift of God, and who it is that saith to thee, Give me to drink; thou wouldest have asked of him, and he would have given thee living water.” This water is equated by Jesus with the waters of everlasting life that forever quench thirst, making a strong connection to the tree of life motif which quenches thirst in like manner as noted before: “Whoso drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life.” The point here is that Jesus has reversed the roles and usurped the symbols of the tree/fountain of life that are culturally associated with womanhood.

[Page 171]But this makes perfect sense to Christianity, for Jesus declares that birth is a central symbol of the atonement and his redeeming power whereby he becomes a symbolic mother to all who are “born again” of him (see John 3:1-3; Moses 6:59; Mosiah 5:7). The difficulty some might have in believing that Jesus would adopt symbols that were culturally associated with womanhood due to gender differences should remember that Jesus also likens himself to a mother hen who gathers her chicks under her wing to nourish them in Matthew 23:37; 3 Nephi 10:4-6; D&C 10:65; cf. Psalms 91:4. Consequently, baptism and the closely related ordinance of the sacrament can be viewed as a tree of life to those who partake, for these rituals represent at once a watery purification, spiritual nourishment, rebirth, the beginning of a journey, and preparatory for entering the temple, even though they also contain within their meaning the idea of “having arrived” at eternal life, resurrection, the sabbath rest, etc. This is possible, because in these initial moments and rituals, the symbols are affirming the promise that “if ye entered by the way ye would receive” (2 Nephi 31:18). In other words, we get to partake of the tree of life at the beginning of new spiritual life, for it anticipates and affirms God’s promise that we shall partake of it fully in the heavenly city at the end of our journey.

In spite of Jesus’s usurpation of the Lady’s symbols, there is still deep acknowledgement in John’s gospel of woman’s original connection to these divine motifs. In the transition of Jesus from mortality to resurrected Lord, John constantly portrays women overseeing this grandest of events. It is a woman, Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, who anoints Jesus with costly oil. An act that Jesus declares was related to his burial (John 12:1-7). At the moment of his death, John portrays Jesus calling attention to his mother — “Woman, behold thy son!” and to his disciple “Behold, thy mother!” (John 19:25-27). The very next moment John records Jesus saying, “I thirst” (John 19:28). Could John have understood in this moment the irony of Jesus’ mother, the supreme mortal personification of the tree of life and living water, standing helpless while her royal son — he who wields the proverbial rod of iron (Revelation 2:27) — dies on a man-made tree of torture and received vinegar instead of cool, living water?

John’s description of the actual burial and resurrection can also be read as a birth scene, for Jesus’ body was placed in a garden of trees, in a virginal tomb “wherein was never man yet laid” (John 19:41), and Jesus presumably comes forth naked, indicated by his linens left neatly folded behind as if to call attention to that very point.

[Page 172]Finally, it is a woman who is the first to see the newly “born” Son of God (John 20:11-18). True to the Near Eastern background, a woman is present at the moments of cosmic transition, whether real or in ritual.

If, as in the Egyptian culture, there are symbolic encounters with two trees of life in the course of the Israelite temple theology, one in the courtyard in relation to purification preceding the arrival at the full tree of life inside the temple. Then the possibility that there are two paths leading to each tree, an initial path outside the temple and a second one inside, needs exploring as well. Indeed, the Egyptians have a concept of the Two Ways or Paths that lead to eternal life. Could it be that the path of Lehi’s vision is a representation of the path taken by those people of the world who are seeking to make their first initial contact with the promise of eternal life, whereas 2 Nephi 31 speaks of another path on which one must press forward, after baptism, in order to make that promise sure? Exploring these paths will have to await a future time.

Go here to leave your thoughts on “The Lady at the Horizon: Egyptian Tree Goddess Iconography and Sacred Trees in Israelite Scripture and Temple Theology.”