[Page 319]Abstract: This article describes examples of the sacred embrace and the sacred handclasp in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms of ancient Egypt, in ancient Mediterranean regions, and in the classical and early Christian world. It argues that these actions are an invitation and promise of entrance into the celestial realms. The sacred embrace may well have been a preparation, the sacred handclasp the culminating act of entrance into the divine presence.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See Stephen D. Ricks, “The Sacred Embrace and the Sacred Handclasp in Ancient Mediterranean Religions,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 159–70. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/ancient-temple-worship/.]

The Sacred Embrace in Ancient Egypt: Introduction

A number of years ago, while planning to travel to Egypt to visit our son who was studying Arabic there, my wife and I were encouraged [Page 320]to visit the White Chapel of Senusret I at the Temple of Karnak in Luxor, Egypt. There, we were told, we would see a number of scenes of “sacred ritual embrace,” in which the king is depicted being embraced by one of the gods before being received into heaven (the “Fields of Bliss”). We were also told that there were several other scenes of sacred embrace in the temple complex at Karnak. We went expecting to see a few at Karnak and elsewhere but were nearly overwhelmed with the embarrassment of ritual riches we saw there at that time and on a subsequent visit: many scores of scenes of embrace (at least 150) at the temples at Karnak, at the ancient Egyptian Ptolemaic temple at Philae near modern Aswan, Egypt, as well as at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Here we will focus on examples of the sacred embrace in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms of ancient Egypt.

The Sacred Embrace in

Ancient Egyptian Iconography

Figure 1: The Divine Horus (with a falcon head) embraces the Royal Horus on the Qa Hedjet Stela

One of the earliest scenes of sacred embrace may be seen on the (Hor) Qa Hedjet stela (Figure 1), dating from the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom around the middle of the 27th century bc.1 The stela itself is made of polished limestone and shows the divine Horus (depicted with a falcon head) embracing the royal Horus with foot by foot, knee facing knee, hand to back, and mouth to nose so that the divine Horus might “inspire” (i.e., breathe life) into the royal Horus.

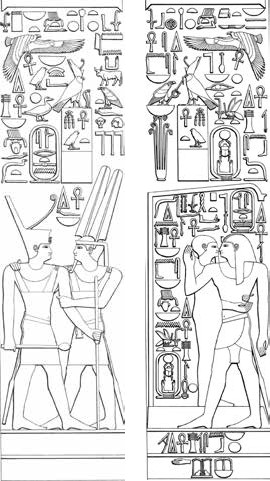

An eleven-foot pillar from the Middle Kingdom (Figure 2) celebrates the sed (royal jubilee) festival of the Egyptian King Senusret (reigned 1971–1925 bc) in about 1940 bc. Two sides of this four-sided pillar group are illustrated. In the first scene Senusret stands opposite the god Amon, who faces him foot by foot, knee to knee, and hand on back. In the fourth panel Senusret faces the god Ptah from the right; both hands grasp his back, and he stands face to face in order to breathe life into him.

Figure 2: Left: The pharaoh Senwosret faces the god Amon, who embraces him. Right: Senwosret is embraced by Ptah, who faces him from the left.

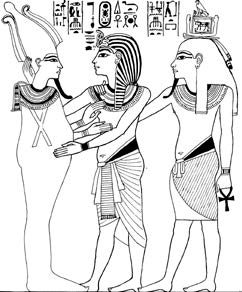

The final scene (Figure 3) is from a New Kingdom relief from the tomb of Tutankhamun who died as a very young king in his teens in the 14th century bc. The discovery of his tomb by the British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1923 created an international sensation. Tutankhamun [Page 321]— known popularly as “King Tut” — ruled Egypt after the death of Akhenaten, the king of Egypt who introduced the monotheistic belief in the solar disk Aten in the 15th century bc. This sacred embrace scene illustrated below is part of a larger “Opening of the Mouth” scene in which Tutankhamun is being prepared to enter the Fields of Bliss. In the final, culminating scene, Tutankhamun, accompanied by his ka, embraces Osiris, who is depicted as a man in a sarcophagus. In this scene the deceased king faces Osiris with foot facing foot, knee facing knee, the king’s hand behind the head of Osiris, with his arm around the deity’s waist. Osiris, in turn, touches the king’s chest. As Tutankhamun embraces Osiris he is described as “given life for all time and eternity.”2 The rite, according to Svein Bjerke, “transfers vital power [his ka3] from the god to the king.”4 What is recorded in a ritual for Amenophis I (18th dynasty, 16th to 15th centuries bc) may also be understood for Tutankhamun:

You go forth from embracing your father Osiris

You revive through him, you are made whole through him.5

Figure 3: Tutankhanum (middle), accompanied by his ka (right),

embraces Osiris (left), from the tomb of Tutankhamun, ca. 1320 bc

The Sacred Embrace by Mother Deities

in the Religious Literature of Ancient Egypt

The scenes illustrated above are of male deities embracing kings. But the sacred embrace by mothers, or mother deities, was also a concept that was current in the sacred literature of ancient Egypt. “The embrace of the individual entering the afterlife by his mother,” observes the distinguished Egyptologist Jan Assmann, “is an idea that has its origins in the cult of the dead. The dead king as Osiris embraces his mother Nut and revives in her arms.”6 This embrace by the goddess can be understood “in connection with the entrance of the deceased into the afterlife as overcoming the separation of mother and child at birth.”7 Thus, for example, in the 11th [Page 322]hour ritual of the “Ritual of the Hours” from Edfu we read: “Your mother, who embraces you, has purified your bones, she causes you to be healthy and full of life … Your father embraces you [lit., ‘wraps his arm around you.’] You lead millions on the western horizon.”8 On the Pyramidion Leiden K 1 from the reign of Amenophis III (18th Dynasty, 14th century bc), Isis is substituted for Hathor, the mother of the sun god:

You go forth, as you are well,

From the embrace of your mother Isis.9

The Purpose of the Sacred Embrace

Scenes in which a god or goddess embraces a king “often appear,” observes the Egyptologist Horst Beinlich, “since the embrace by a deity appears to have been a privilege of the king … . Such scenes of embrace on pillars may have to do with a god’s greeting the king.”10 Beinlich further notes that “through close contact with the body of the deity … the king is (in the role of a child) newly enlivened, transfigured, and receives the power of the ka.” The sacred embrace is thus part of an initiatory ceremony in which the king is made priest as well: “Before becoming a king, he must first become a priest, and for that also he must be purified with divine water, receive a garment, be crowned, and be led into the sanctuary to receive” the god’s embrace.11 “The embracing (Eg. shn) of [Page 323]the king by the god”12 is the definitive consecration of the king, “who at that moment becomes fully consecrated, crowned, and sanctified.”13 The embrace represented on the walls of the inner sancta of Egyptian temples — forbidden or inaccessible to others — may be either the preparatory embrace by a priest representing a god at his coronation when he is “consecrated, crowned and sanctified” or also the confirmatory embrace by the god at the time of the king’s passing beyond the halls of judgment to the Fields of Bliss.

By way of conclusion, we may note that (1) in scenes of sacred embrace, the deity faces the king foot by foot, knee to knee, hand to back, and mouth to nose to “inspire” (breathe life or vital force — his ka) into him; (2) scenes of sacred embrace in ancient Egyptian religion occur in the Holy of Holies — the most sacred and (to the unauthorized) inaccessible precincts of the temple (the center of the temple, the rear of the temple, the side chapel); (3) scenes of sacred embrace are found throughout ancient Egypt (from the Delta to Philae) and throughout Egyptian history (from the Old Kingdom on); (4) the sacred embrace is preparation for entrance into the presence of the gods; and, finally, (5) although the scenes depict only royalty being embraced by the gods and entering into their presence, in ancient Egypt everyone — men, women, and children — of whatever social status and era, were candidates for entrance into a blessed afterlife.14

The Sacred Handclasp

in Ancient Mediterranean Religions

Figure 4: Late fifth-century bc Greek gravestone showing Philoxenos grasping the hand of his wife Philoumene

On a gravestone dating to the end of the fifth century bc from Attica in Greece, the husband Philoxenos (whose name, as well as that of his wife, is carved in the register above his head) is seen grasping the right hand of his wife Philoumene in a solemn and ceremonial handclasp (Figure 4). This handclasp, the description informs us, “was a symbolic and popular gesture on gravestones of the Classical period,” which could represent “a simple farewell, a reunion in the afterlife, or a continuing connection between the deceased and the living.”15 The handclasp, known in Greek as dexiosis and in Latin as dextrarum iunctio, means “giving, joining of right hands” and is to be found in classical Greek art on grave stelai but especially in Roman art, where it is to be seen on coins and sarcophagi reliefs as well as in Christian art in mosaics and on sarcophagi reliefs.

Why were early Christians in the Roman world also depicted performing the dextrarum iunctio? They did so in part because they agreed with the non-Christian Romans that “fidelity and harmony are demanded in the longest-lasting and most intimate human relationship, [Page 324]marriage.”16 But they also did so because they accepted, perhaps, the ancient Israelite view that marriage was a sacred covenant17 and further because they understood “marriage,” in the words of the Protestant scholar Philip Schaff, “as a spiritual union of two souls for time and eternity.”18 For the ancient Christians, the sacred handclasp — the dextrarum iunctio — was a fitting symbol for the most sacred act and moment in human life.

The Sacred Handclasp in Scenes of Introduction to the Heavenly Realms in the Classical and Early Christian World

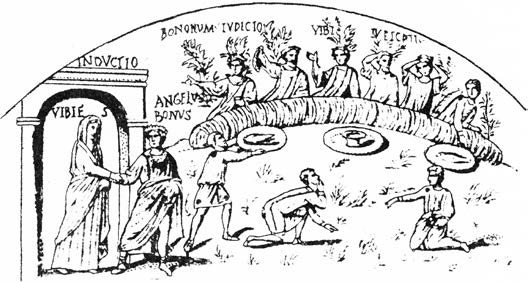

The dexiosis/dextrarum iunctio is used as a symbol of union, harmony, equality, and fidelity in marriage. But the right hand is also given in scenes of introduction into the realm of the blessed in ancient Mediterranean religions. The first scene (Figure 5) is from a series of illustrations from the tomb complex of the Sabazian [Page 325]priest Vincentius near Rome, dating from the second century.19 One depicts the “good angel” (labeled in the scene as bonus angelus)20 grasping Vibia, the deceased wife of Vincentius, by the right hand in a dextrarum iunctio and leading her into a place where the blessed (some of whom are identified by name) are enjoying a celestial banquet.

Figure 5: The “good angel” (Lating bonus angelus) grasps the hand of Vibia to lead her to the banquet of the blessed, from a Sabazian tomb near Rome

The hand is held out to introduce individuals into the celestial realms. Two other scenes are mosaic illustrations from Christian churches built in the sixth century ad in Ravenna, Italy, one from the Basilica of San Vitale (Figure 6), the other from the Basilica of Sant Apollinare in Classe (Figure 7). Each of the scenes shows the altar on which Melchizedek is making an offering to the Lord. In the mosaic in St. Apollinare in Classe, Melchizedek, clad in a purple cloak and offering bread and wine at the altar, is flanked to the viewer’s left by Abel, who holds a sacrificial lamb toward the altar, and, to the viewer’s right, by Abraham with his young son Isaac, whom he gently pushes to the altar21 (in the scene in San Vitale, Melchizedek is at the viewer’s right, opposite Abel holding the lamb). In front of the altar is the so-called “Seal of Melchizedek,” two golden interlocking squares.22

Figure 6: Abel and Melchizedek making an offering, with the hand reaching from behind the veil, Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

Figure 7: Abel, Melchizedek, Isaac, and Abraham surround the altar, with the hand reaching from behind the veil, Basilica of St. Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, Italy.

Behind the figures (in St. Apollinare, to the right of Melchizedek; in San Vitale, above the altar) there is a right hand stretching out from behind the veil, inviting the figures (and, by implication, the viewer) to grasp it in the dextrarum iunctio in order to be introduced into the heavenly realms behind the veil.

In both actions depicted in these scenes — the sacred embrace and the sacred handclasp — there is an invitation and promise of entrance [Page 326]into the celestial realms. The sacred embrace may well have been a preparation, the sacred handclasp the culminating act of entrance into the divine presence.

Figure Credits

Figures 1-3 appear courtesy of Brigham Young University’s Neal A Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. Figure 4 is courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Our thanks to the Maxwell Institute for Figure 5, which was redrawn from an image found in Johannes Leipoldt, Die Umwelt des Urchristentums (Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1967), 3:fig. 60. Figures 6 and 7 are used with the kind permission of Val Brinkerhoff.

Given that this episode includes the giving of a new name to Jacob (symbolizing Jacob’s entering a new, higher stage in his life), the angel’s hesitance to disclose his name, may we not also understand the Hebrew ye’aveq (“wrestle”) in an additional sense of “embrace.”

Go here to leave your thoughts on “The Sacred Embrace and the Sacred Handclasp in Ancient Mediterranean Religions.”