Abstract: Nothing was more terrifying in the ancient world than a siege. Besiegers disregarded normal conventions of war and either utterly slaughtered or enslaved a city’s residents. Nephi used siege warfare imagery — including fire arrows, blinding, and being led away into captivity — to teach his brothers the importance of holding fast to Christ’s iron rod (see 1 Nephi 15:24). By analyzing this scripture and the vision of the Tree of Life in context of ancient siege warfare, we learn how Satan besieges God’s people, cuts off their access to the Tree of Life, draws them away through scorn, blinds them, and yokes them with a yoke of iron. Christ, in contrast, extends his iron rod through Satan’s siege, inviting us to hold fast to his word, accept him as our covenant family head, and join him in his work by speaking his word. Those who act on Christ’s invitation will find safety and joy in Christ’s kingdom.

Shortly after Nephi received his vision in 1 Nephi 11–14, he taught a vital principle to his brothers — that the word of God provides spiritual protection from Satan’s temptation and power: “Whoso would hearken unto the word of God, and would hold fast unto it, they would never perish; neither could the temptations and the fiery darts of the adversary overpower them unto blindness” (1 Nephi 15:24). Since this principle is absent from the King James Version of the Old Testament, one might wonder where Nephi developed this idea. The Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis may indicate that Nephi had access to a similar [Page 2]teaching on the Brass Plates.1 However, even if Nephi had read Moses 4:4 — or something similar — Nephi’s insights still constitute a significant expansion on the information there. The timing and context in which Nephi states the principle — directly after experiencing his magnificent vision — strongly indicates that angelic instruction, rather than past scripture study, is the likely source of Nephi’s understanding. A close comparative analysis of Nephi’s vision with 1 Nephi 15:24 shows that the angel selectively chose visionary manifestations that helped Nephi clearly understand (a) Satan’s efforts to besiege Zion, its inhabitants, and all who seek refuge there, and (b) that the only way to withstand Satan’s siege is to give heed to God’s true word. The purpose of this paper is to illuminate connections between 1 Nephi 15:24, Nephi’s vision, and the cultural context in which Nephi received that vision, in order to better understand how he hoped that his brothers and all of his readers might endure Satan’s incessant efforts to draw people out and lead them away captive from Christ’s Kingdom.

1 Nephi 15:24 is given amidst a question-and-answer session between Nephi and his older brothers. Directly after experiencing his vision of the Tree of Life, Nephi saw his brothers arguing over the meaning of their father’s dream. Unlike Nephi, they had not “[looked] unto the Lord as they ought” (1 Nephi 15:3), and because Lehi had not explained the symbols of his visionary experience, Nephi’s brothers were left in [Page 3]the dark as to their meaning. After taking some time to recover from his own vision, Nephi directly answered their questions. During this conversation, they asked their younger brother, “What meaneth the rod of iron which our father saw?” (1 Nephi 15:23). Nephi answered that “it was the word of God; and whoso would hearken unto the word of God, and would hold fast unto it, they would never perish; neither could the temptations and the fiery darts of the adversary overpower them unto blindness, to lead them away to destruction” (1 Nephi 15:24).

In this conversation, Nephi used fiery darts, blindness, and being led away captive to illustrate the nature of Satan’s attacks. All these images can be references to siege warfare. Why would Nephi use such imagery in communicating with his brothers? Nephi’s family would have been familiar with sieges. Although the absolute dating of Lehi’s departure from Jerusalem is still open to minor adjustments, Lehi’s family may have endured Nebuchadnezzar’s first siege of Jerusalem. Even if they departed before the siege occurred,2 the sieges of past conquerors — namely the Egyptians and Assyrians3 — would have been part of their [Page 4]family history, particularly since Lehi’s near ancestors were likely refugees of Manasseh.4

Sieges were unmatched in their brutality in the ancient world. A successful siege typically ended with the slaughter and/or enslavement of a city’s entire populace. Homer expressed King Priam’s fear of the eventual pillage of Troy in these words: “After I have seen my sons slain and my daughters [hauled] away as captives, my bridal chambers pillaged, little children dashed to earth amid the rage of battle, and my sons’ wives dragged away by the cruel hands of the Achaeans; in the end fierce hounds will tear me in pieces at my own gates after some one has beaten the life out of my body with sword or spear.”5 In siege warfare, conventional battle standards of honor and prowess were completely disregarded. Whereas in the field of battle victors took their enemies prisoner and often freed them after ransom, sieges were usually culminated by conquerors hunting their enemies through the streets, killing without restraint, and enslaving those they spared. Nothing would have inspired a city’s residents to fear like an impending siege.6

Perhaps Nephi desired to inspire the same sort of urgent trepidation in his brothers. Nephi believed his father’s words concerning Jerusalem’s siege and destruction and he was grateful that the Lord had seen fit to spare their family such a fate (see 1 Nephi 7:13–15). However, he also knew that Laman and Lemuel did not believe their father. In addition, Nephi had just heard Lehi state that Laman and Lemuel “partook not of the fruit” (1 Nephi 8:35), a fruit that Nephi now understood represented the Atonement of Jesus Christ.7 Nephi knew what his brother’s potential rejection of the Messiah meant for them. Thus, Nephi used language that would clearly communicate his brothers’ dire circumstances, and nothing would have communicated immediate danger like siege imagery. Such language aptly fits his efforts to “exhort [his brothers] with all the energies of [his] soul” (1 Nephi 15:25). In addition, Nephi’s [Page 5]use of this symbolism may reflect his emotional reaction to much of his vision. Nephi said that he “considered [his] afflictions were great above all,” because he had just witnessed the wholesale “destruction of [his] people” (1 Nephi 15:5). Since sieges also resulted in the utter destruction of a people, this would have been a logical connection for Nephi to draw.

A final reason why Nephi might use siege symbolism is simply because his vision resembled an ancient siege. As we analyze the elements of the vision in the context of siege warfare, we see that Satan and his forces (represented by the great and spacious building):

- Besiege Christ’s earthly kingdom (portrayed by the Tree of Life).

- Cut off the path to Christ’s kingdom with temptations (mists of darkness).

- Draw away Christ’s followers through scorn (fiery darts).

- Spiritually blind Christ’s followers (mists of darkness).

- Captivate those who fall away (Satan’s yoke of iron).

In 1 Nephi 15:24, Nephi first highlights two tools that Satan uses to “overpower [God’s children] unto blindness” — namely temptations and fiery darts. During his vision, the angel explains to Nephi that the temptations of Satan are like “mists of darkness … which blindeth the eyes, and hardeneth the hearts of the children of men, and leadeth them away into broad roads, that they perish and are lost” (1 Nephi 12:17). The mists of darkness fit well with similar imagery coming from texts both before and after Nephi’s time.8 However, Nephi’s use of fiery darts as imagery for Satan’s efforts seems to be a new idea. As has been argued by some scholars, fiery darts (perhaps mistranslated as “arrows”) are mentioned in Psalm 7 as a weapon in the hands of the Lord as he fights defensively for the faithful. Some have wondered why Nephi reversed this imagery, using the same object — which had previously been used to teach about Yahweh’s protection — now as a symbol of Satan’s offensive attacks.9 Nephi’s inspired reasoning can be better understood by studying how fire arrows were used in ancient siege warfare.

[Page 6]In the ancient Near East, fire arrows were used in siege warfare on both the defensive and offensive sides. As a defensive weapon, they were an effective weapon against siege engines. At least 100 years before Lehi, Assyrian siege engines were described as wrapped in leather to protect them against flame arrows and other burning projectiles.10 This defensive use of fire arrows may help illuminate the imagery in Psalm 7, where the psalmist portrayed the Lord as a defender against their enemy’s rage and persecution. On the other side of the battle besiegers used fire arrows as an offensive weapon to terrify, burn out, and overcome their hunkered victims. For example, during a siege of Athens, the Persians shot arrows wrapped with burning hemp fibers into the barricades surrounding the Athenian Acropolis, successfully destroying them.11 Thus, for the besiegers, fire arrows were particularly useful in rendering their victim’s defenses ineffectual, making it possible for an overpowering assault. This offensive application of fire arrows is likely Nephi’s intent in 1 Nephi 15:24.

Of particular interest is that the metaphorical fire arrows of scoff and scorn are fired from a great and spacious building. When juxtaposed against the great and spacious building, the Tree of Life stands like God’s city12 with a “terrible gulf [that] divideth” (1 Nephi 12:18) Christ’s followers from their persecutors. This gulf is like the moats that surrounded many ancient cities.13 However, the gulf in Nephi’s vision has one stark difference from the man-made moats of Nephi’s day. The gulf of Nephi’s vision is unassailable because it represents the “justice of the Eternal God.” This “great and terrible” (1 Nephi 12:18) gulf creates [Page 7]the only truly safe place from Satan’s control — near the Tree of Life. Thus, Satan’s siege of the Tree of Life may be akin to the doomed siege by Zemnarihah and the Gadianton robbers in 3 Nephi 3–4. Just as Zemnarihah’s men were powerless due to the “scantiness of provisions among the robbers” (3 Nephi 4:19), Satan and his followers are powerless against God’s justice. Perhaps not coincidentally, after defeating the Gadianton robbers, Lachoneus’ people hung Zemnariahah on a tree and then cut down the tree. According to John Welch, the people of Lachoneus may have been following an ancient Israelite practice of cutting down the tree upon which malefactors were hung. Maimonides explained that this was done so that the people can’t say “this is the tree on which so-and-so was hanged,” thus removing the reminder of the malefactor and his crime.14

The language of the prayer in 3 Nephi 4:29 suggests that the people of Lachoneus — in addition to following Israelite capital punishment practice — may have cut down the tree as a symbolic speech-act. After they fell the tree, they prayed that the Lord would “preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth” (3 Nephi 4:29). Lachoneus and his people knew that if they stayed faithful to God that the Lord would bring to pass the fall of all secret combinations that sought to destroy them.

Secret combinations are a primary manifestation of the great and spacious building (see 1 Nephi 12:18–13:6; 2 Nephi 26:22). The angel taught Nephi that the great and spacious building included “all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people, that shall fight against” God and his people and that eventually these assailants shall fall, and “the fall thereof [would be] exceedingly great” (1 Nephi 11:36). Thus, not only does God’s justice provide protection for God’s people within the environs of the tree, the Lord, in his own time, will cause that the “great pit which hath been digged for the destruction of men shall be filled by those who digged it, unto their utter destruction” (1 Nephi 14:3).

This impassable gulf between the great and spacious building and the Tree of Life does not leave Satan completely powerless, however. Even though Satan’s forces cannot infiltrate God’s city, they use a great and [Page 8]spacious building to rain down their fiery arrows of mockery, scoff, and scorn. In Lehi’s vision, the constant barrage of scoff and scorn negatively affects many who have partaken of God’s goodness. They become ashamed, leave the safety of Christ’s kingdom, and “[fall] away into forbidden paths” (1 Nephi 8:28). Lehi describes the building as being “in the air, high above the earth” and “filled with people” who mock and point fingers “towards those who … were partaking of the fruit” (1 Nephi 8:26–27).

Typically depicted as a large castle-like structure in artistic depictions, Lehi’s description of the great and spacious building also matches that of ancient siege towers. These towers were powerful tools in overcoming even highly fortified cities that had strong defenses. They towered over most structures of their day, and they were often built to match or exceed the height of the city’s fortification — which was frequently higher than 30 feet. These siege towers were filled with soldiers, just as Lehi described the great and spacious building being filled with people (1 Nephi 8:27). The siege engine — a mobile variety of the siege tower — rolled on wheels that were often hidden underneath the structure. From the defenders raised position on the city walls such a concealment may have made the siege tower look as if it were floating. Attackers would build or roll the siege tower within firing distance of the city wall, where archers could eliminate rampart defenses. (See Figure 1.) Such structures were used in the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem that Lehi’s family fled to avoid.15 One example of these siege towers bears particular similarity to Nephi’s description. In the eighth century bc, the Kushite king Piye attacked lower Egypt. To conquer the city of Ashmunein, he erected a “wooden siege-tower, from which the Kushite archers could fire down into the city” (emphasis added).16 Nephi likely knew something of Piye’s conquest, particularly since Nephi had exposure to Egyptian culture and language.

[Page 9]

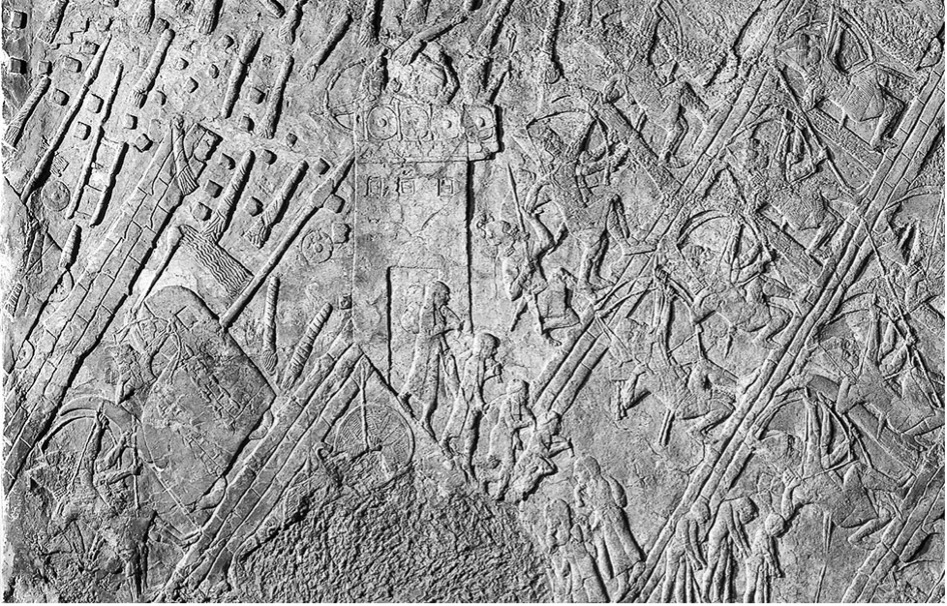

Figure 1. Relief on gypsum wall panel from Ninevah showing the siege of Lachish, in Judea. The siege engine is shown going up man-made ramps toward the wall with archers atop it. Defenders fire arrows and throw torches from defensive towers in efforts to set the engine ablaze. Assyrian soldiers with ladles pour water to stop their efforts. Prisoners are depicted leaving the fortifications as slaves. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Other corroborating reasons for Nephi’s use of fire arrows can be found by textual analysis. In Hebrew the word zîqôṯ can be translated as firebrands or fire arrows, as it is in Proverbs 26:18.17 Alternatively, in most other places within the Old Testament, zîqôṯ is translated as fetters or chains. This duality of meaning may have been a prime opportunity for a wordplay by Nephi. The ultimate purpose of Satan’s fiery arrows is to bring us into his burning and bonding chains. Given the Book of Mormon’s repeated use of the imagery of chains in discussions about Satan, recognizing such a wordplay may offer another feasible line of interpretation (discussed below). It is also worth noting that Satan is described as an “adversary” in 1 Nephi 15:24, which is different than the devil and Satan titles used in the text of Nephi’s vision. In the King James Bible, several words are translated as adversary. Śāṭān (Satan) is the most common and refers to someone who accuses or withstands. In Exodus 23:22, ṣûr is the Hebrew word translated as adversary and has more [Page 10]specific connotations, namely, to be an adversary who confines, binds, or besieges. Thus, in 1 Nephi 15:24, ṣar — the noun form of ṣûr — may be a better word than śāṭān in “fiery darts of the adversary” because it is a natural companion to the siege weapon imagery of fiery darts.18

In all successful sieges, simply shooting weapons into a city was not enough. The assailants also needed to cut off access both into and out of the city, and in Nephi’s vision Satan does so by enveloping the lone entry point to the Tree of Life with his mists of darkness. As mentioned earlier, the angel explained that the mists of darkness are a representation of Satan’s temptations. Then, the angel showed Nephi a deeply personal example of these temptations among Nephi’s descendants, who give in to pride, are overpowered, and destroyed. In addition, Nephi saw the great and abominable church strip the Jewish record of many parts “which are plain and most precious; and also many covenants of the Lord” (1 Nephi 13:26). This stripping caused the book to lose some of its essential power and it became a less reliable guide for would-be followers seeking the living Christ, represented by the tree. As a result, the Gentiles are blinded, and their hearts grow hard (see 1 Nephi 13:27). Without an effectual iron rod, “an exceedingly great many do stumble” and “Satan hath great power over them” (1 Nephi 13:29).19

In addition to cutting off access to the tree of life, the mists of darkness are effective in blinding its victims and may be seen as smoke that stings and blinds the eyes of people looking for a place of refuge. Lehi mentions that those who were blinded by the mists of darkness “wandered off and were lost” (1 Nephi 8:23). Likewise, those that partook of the fruit but were ashamed — due to Satan’s fiery darts of mockery — “fell away into forbidden paths and were lost” (1 Nephi 8:28). These “strange roads” (1 Nephi 8:32) are apparently filled with blind wanderers who are unable to discern their location or direction.

Both the biblical and extrabiblical record show that blinding slaves was a common practice in the ancient near east. The Philistines blinded Samson after his capture (Judges 16:21). Nahash, the Ammonite, besieged Jabesh-gilead and offered to put out only one eye of each inhabitant as a condition of their surrender (1 Samuel 11:2). The Assyrians were particularly famous for blinding their siege victims — along with other countless inhumane punishments — as a warning to others that might [Page 11]be tempted to resist their conquest. Assyrian kings often took pleasure in personally blinding prisoners.20 King Shalmaneser I claimed to have put out the eyes of over 14,000 prisoners.21 Nephi’s own sovereign, Zedekiah, succumbed to a fate that bears interesting similarity to what Nephi describes in 1 Nephi 15:24. Zedekiah’s forces were overpowered by a superior Babylonian army. The king was then blinded, bound in brass chains, and led away captive to Babylon (see 2 Kings 25:7).

In Nephi’s vision, the angel states that the great and abominable church desires to “blind the eyes and harden the hearts of the children of men” (1 Nephi 13:27). Thus, Satan’s forces expend great effort in taking away “from the gospel of the Lamb many parts which are plain and most precious; and also many covenants of the Lord” (1 Nephi 13:26). The word of God, then, is always at the center of Satan’s crosshairs in his efforts to cut off access to the tree and blind those he wishes to capture. If he — through his great and abominable network — can in some way “pervert the right ways of the Lord” (1 Nephi 13:27), then spiritual blindness among Christ’s followers is inevitable.

However, simply overpowering and blinding Christ’s followers is not Satan’s ultimate objective. Even after obscuring the entrance to the Tree of Life with sundry temptations, overpowering God’s people with his fiery darts of scorn and mockery, and spiritually blinding those who fall away, Satan’s siege of the Tree of Life is not complete until the residents of the Tree of Life are led away to destruction and into the pit of hell (see 1 Nephi 14:3). Satan’s true desire is to take Christ’s followers captive. The angel teaches Nephi about the strength of Satan’s captivity by showing Nephi “saints of God” who are enslaved by a “yoke of iron” (1 Nephi 13:5). The imagery of an iron yoke had particularly impactful meaning in Nephi’s day and was directly related to siege warfare. In Old Testament times, a yoke was made of two pieces: The ʿōl, which was the part that encompassed the neck, and the môṭâ, which was the stave or rod of the yoke.22 While yokes for beasts of burden were fashioned of wood, iron yokes were tools of conquest and slavery. Around the time of Lehi’s departure from Jerusalem, Jeremiah dramatically donned a wooden ʿōl and môṭâ to demonstrate Israel’s fate under Nebuchadnezzar. In protest, [Page 12]the false prophet Hananiah removed the môṭâ from Jeremiah and broke it, professing in the presence of the priests and the people that God had broken Nebuchadnezzar’s hold. Jeremiah responded, “Thus saith the Lord; Thou hast broken the môṭâ of wood; but thou shalt make for them môṭâ of iron…. I have put a ʿōl of iron upon the neck of all these nations, that they may serve Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon” (Jeramiah 28:13– 14). The use of iron in the yoke imagery communicated a sort of long-term permanence to the coming conquest and bondage. Israel would not easily break away from Babylon. The dating of Jeremiah 27–28 to the commencement of the reign of Zedekiah (1 Nephi 1:4) makes it likely that Nephi would have been familiar with Jeremiah’s dramatic use of prophetic simile curses and other symbolic speech-acts in general, and his use of the iron yoke imagery in particular.23

This idea of the potential permanence of Satan’s grasp is later and repeatedly taught in the Book of Mormon through the imagery of chains and cords. Lehi warns Laman and Lemuel to shake off “the chains which bind the children of men, that they are carried away captive down to the eternal gulf of misery and woe” (2 Nephi 1:13). Nephi later writes of Satan’s “everlasting chains … from whence there is no deliverance” (2 Nephi 28:19–22). Alma repeatedly warns of Satan’s desire to “encircle you about with his chains, that he might chain you down to everlasting destruction, according to the power of his captivity” (Alma 12:6; see also Alma 5:9–10; 13:30; 26:14; 36:18). Using cords in connection with this metaphor, Nephi teaches that Satan “leadeth them by the neck with a flaxen cord, until he bindeth them with his strong cords forever” [Page 13](2 Nephi 26:22). Whether by use of chain, rope, or yoke, the Book of Mormon clearly teaches that sin can have long-term negative effects and that, over time, those who become bound find themselves under Satan’s control. This is a fitting emphasis in a book written for the present day, a time when many “call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness” (Isaiah 5:20). If sin is recognized, repentance is often perceived as a quick and easy fix.

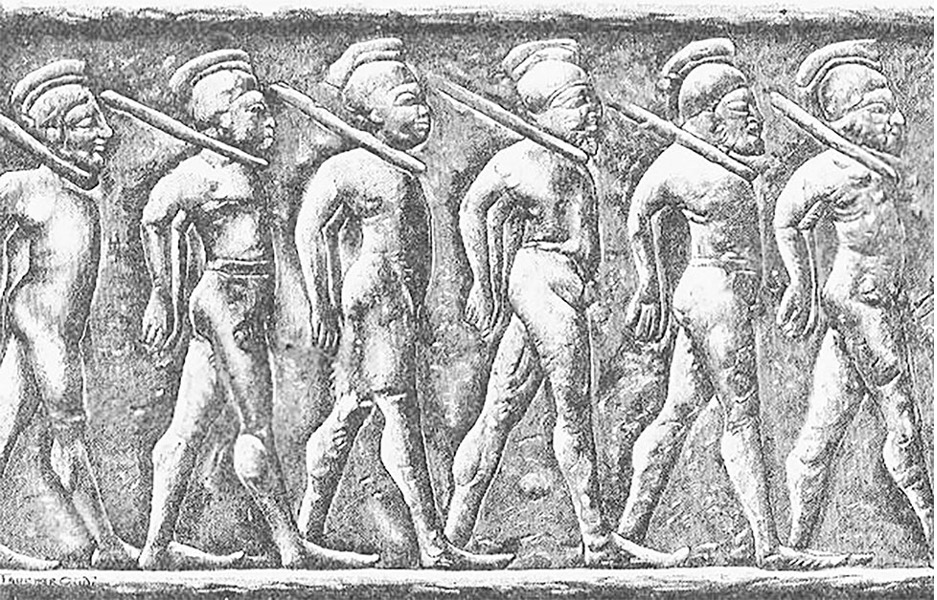

Figure 2. Illustration of relief on Balawat gate of Egyptian prisoners being led away in yokes by Assyrian forces. Drawn by Faucher-Gudin.24

The angel’s use of an iron môṭâ (the rod of the yoke) in describing Satan’s way of leading God’s children to destruction stands in stark contrast with God’s method — which is interestingly also represented by an iron rod. In many artistic representations of Nephi’s and Lehi’s visions, Christ’s rod of iron is portrayed as a railing alongside the path leading to the tree. This portrayal is logical and useful, given that the rod appears to be horizontal in nature, it runs along the path, and people must continually hold to the rod to successfully navigate the mists of darkness.25 However, Nephi may not have interpreted the rod as a hand railing per se since the use of architectural railings were rare in the [Page 14]ancient world.26 Rods were more frequently carried — and while rods could simply be used as walking staffs — they were often used by rulers as scepters (Hebrew: šēḇeṭ),27 a symbol of authority. Hugh Nibley went so far as to say that Aaron’s rod may have been passed down from one generation to another, “loaned by God to his earthly representative from time to time as a badge of authority, and an instrument of miracles, proving to the world that its holder was God’s messenger.”28 Ancient Near Eastern depictions of kings and royal officials often show them holding or wielding their rod of power. Thus, the holder of the rod is seen as a giver of God’s word.29 Nephi would likely have seen kings in Jerusalem holding such symbols and implements of their power as agents of God and may have also been familiar with the Messiah’s use of an iron rod in scripture. In Psalm 2:9, the Messiah wields his unbreakable iron rod to shepherd Israel to safety and salvation.30 While Satan seeks to cut off [Page 15]the entrance of Christ’s domain by obscuring the path with his mists of darkness, Christ divides that darkness by extending his scepter through it to those who will grab it tightly.

Viewing the rod as a scepter may explain why Nephi so quickly comprehended the meaning of the rod without the angel’s assistance. Once the angel had shown him that the Tree of Life represented Jesus Christ’s condescension and atonement, Nephi immediately concluded that the iron rod or scepter — which extends from that tree — represents Christ’s message. Indeed, this scepter symbolism gives the iron rod a personification. Simply thinking of the word of God as words on scriptural pages has the potential of placing them in the abstract and distant past. However, if one sees the living Christ — and his prophetic messengers — as extending Christ’s scepter, one feels invited and in need of not only holding fast to what has been revealed in past scriptural writ, but also to follow the messages coming from God’s living prophets. Laman and Lemuel appeared to understand the importance of keeping the past “statutes and judgments of the Lord, and all his commandments, according to the law of Moses” (1 Nephi 17:22). Yet, they failed to prioritize the words of the living prophets, including Jeremiah and their own father. Thus, they never grabbed Christ’s iron rod and “knew not the dealings of that God who had created them” (1 Nephi 2:12). 31

After Nephi is shown how Satan obscured the path to the Tree of Life and blinded his victims through the great and abominable church’s efforts to remove many plain and precious parts of the Bible, the angel says that the Lord “will bring forth unto them, in mine own power, much of my gospel, which shall be plain and precious, saith the Lamb” (1 Nephi 13:34). Thus, the coming forth of the Book of Mormon can be interpreted as Christ’s paramount work in cutting through Satan’s attempts to obscure the path to the Tree of Life and blind its travelers (see 1 Nephi 13:34–39). Nephi later speaks at length about the centrality of the Book of Mormon in the Lord’s marvelous latter-day work (see 2 Nephi 25–30). Many Gentiles will “believe the words which are written; and they shall carry them forth” (2 Nephi 30:3) to the Jews — who will [Page 16]be “[convinced] of the true Messiah” (2 Nephi 25:18) — and Lehi’s descendants — who “shall be restored unto the knowledge … of Jesus Christ, which was had among their fathers” (2 Nephi 30:5).

Moreover, there are two other valuable insights found by interpreting the iron rod as Christ’s scepter. First, In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word for scepter, šēḇeṭ, is sometimes figuratively translated as tribe. Members of a tribe were under the leadership and authority of their tribal head, the bearer of the scepter.32 Thus, holding fast to Christ’s scepter has a familial connotation. This connotation is emphasized by Nephi later in his writings when he invites all to “take upon you the name of Christ, by baptism … then are ye in this strait and narrow path which leads to eternal life” (2 Nephi 31:13, 18). Nephi understood that those on the path holding to the iron rod were in a familial covenant relationship with Christ. They had come far “by the word of Christ with unshaken faith in him, relying wholly upon [his] merits” (2 Nephi 31:19). However, their work was not done. Being part of Christ’s family means progression. Everyone holding to Christ’s scepter must continue to “press forward” through Satan’s deceptions by “feasting upon the words of Christ” (2 Nephi 31:20).

The second insight is found in the invitation to hold fast to the iron rod. As mentioned, Hugh Nibley theorized that the holder of Aaron’s scepter was God’s messenger on earth. By inviting each of us to hold his scepter, Christ is also obligating us to speak his word with his authority. Thus, holding fast not only implies studying, believing, and following, it also means that each of us are to speak the word of God. As Moses said, “Would God that all the Lord’s people were prophets, and that the Lord would put his spirit upon them!” (Numbers 11:29).

In summary, Nephi’s vision about the meaning of the Tree of Life effectively represents both Christ’s and Satan’s tactics. As they worship at the Tree of Life, Satan lays a ferocious siege against Christ’s people who have partaken of the Savior’s grace. The army in the great and spacious building — that are “among all the nations of the Gentiles, to fight against the Lamb of God” (1 Nephi 14:13) — brutally shower down their fiery darts of persecution and oppression, causing many to fall away. Satan cuts off the entrance to the tree by obscuring the path through various temptations, feeding pride, and altering scriptural messages and meanings, thus effectively blinding the path’s travelers. Finally, he binds the saints of God with an iron yoke and blinds their eyes, enslaving them to his will. However, Christ does not abandon his people. Through the [Page 17]darkness, he extends his rod and invites everyone to hold fast to that word, accept his covenant rule, and spread his message. As his covenant saints scatter across the earth — though they are few — the Lord arms them “with righteousness and with the power of God in great glory” (1 Nephi 14:12, 14).

Figure 3. Atop his stele, Hammurabi is depicted as holding his rod (scepter) and speaking his law while his officer raises his right hand. Louvre Museum. “Stele of Hammurabi,” © Mbzt, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

By juxtaposing the iron rods of Christ and Satan, we clearly see the character and desire of these two eternal adversaries. On one hand, Satan seeks to destroy agency by making people captive to his will. He wishes to weigh people down with his iron rod of sin, despair, and shame. On the other hand, Christ invites all to him by continually extending his word. All a person needs to do is hold fast and consistently press forward [Page 18]on the covenant path. On that path, all are under his shepherding rule. They are guided to the Tree of Life, where they find joy (see 1 Nephi 8:12). And while Satan will continue to rain down his fiery arrows of scoff and scorn, if Christ’s followers “[heed] them not” (1 Nephi 8:33), Satan cannot overpower them. One of the primary ways in which Christ extends his word is through the Book of Mormon. In a time where Satan’s siege of the Tree of Life is resulting in so many casualties, holding fast to Christ’s word, particularly the Book of Mormon, is more important than ever. Unlike Satan, Christ’s word is offered freely, without compulsion. Christ honors our agency to choose between eternal life and everlasting captivity (see 2 Nephi 2:27). We have the choice to hold to the rod and press forward towards Christ’s promises or to let go and withdraw, thus becoming subject to Satan’s attacks and eventual long-lasting control.

Go here to see the 4 thoughts on ““Withstanding Satan’s Siege through Christ’s Iron Rod: The Vision of the Tree of Life in Context of Ancient Siege Warfare”” or to comment on it.